Mamluks MEET THE…

advertisement

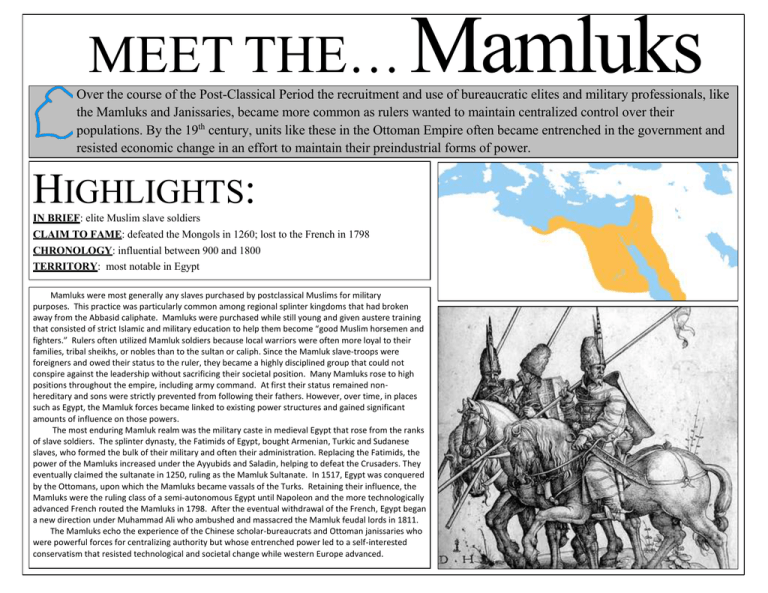

MEET THE… Mamluks Over the course of the Post-Classical Period the recruitment and use of bureaucratic elites and military professionals, like the Mamluks and Janissaries, became more common as rulers wanted to maintain centralized control over their populations. By the 19th century, units like these in the Ottoman Empire often became entrenched in the government and resisted economic change in an effort to maintain their preindustrial forms of power. HIGHLIGHTS: IN BRIEF: elite Muslim slave soldiers CLAIM TO FAME: defeated the Mongols in 1260; lost to the French in 1798 CHRONOLOGY: influential between 900 and 1800 TERRITORY: most notable in Egypt Mamluks were most generally any slaves purchased by postclassical Muslims for military purposes. This practice was particularly common among regional splinter kingdoms that had broken away from the Abbasid caliphate. Mamluks were purchased while still young and given austere training that consisted of strict Islamic and military education to help them become “good Muslim horsemen and fighters.” Rulers often utilized Mamluk soldiers because local warriors were often more loyal to their families, tribal sheikhs, or nobles than to the sultan or caliph. Since the Mamluk slave-troops were foreigners and owed their status to the ruler, they became a highly disciplined group that could not conspire against the leadership without sacrificing their societal position. Many Mamluks rose to high positions throughout the empire, including army command. At first their status remained nonhereditary and sons were strictly prevented from following their fathers. However, over time, in places such as Egypt, the Mamluk forces became linked to existing power structures and gained significant amounts of influence on those powers. The most enduring Mamluk realm was the military caste in medieval Egypt that rose from the ranks of slave soldiers. The splinter dynasty, the Fatimids of Egypt, bought Armenian, Turkic and Sudanese slaves, who formed the bulk of their military and often their administration. Replacing the Fatimids, the power of the Mamluks increased under the Ayyubids and Saladin, helping to defeat the Crusaders. They eventually claimed the sultanate in 1250, ruling as the Mamluk Sultanate. In 1517, Egypt was conquered by the Ottomans, upon which the Mamluks became vassals of the Turks. Retaining their influence, the Mamluks were the ruling class of a semi-autonomous Egypt until Napoleon and the more technologically advanced French routed the Mamluks in 1798. After the eventual withdrawal of the French, Egypt began a new direction under Muhammad Ali who ambushed and massacred the Mamluk feudal lords in 1811. The Mamluks echo the experience of the Chinese scholar-bureaucrats and Ottoman janissaries who were powerful forces for centralizing authority but whose entrenched power led to a self-interested conservatism that resisted technological and societal change while western Europe advanced.