- Humane Learning

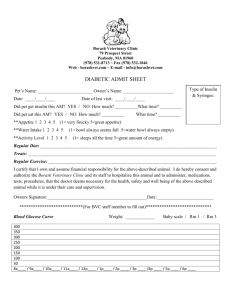

advertisement