excavation is an inherently and unavoidably destructive process!

advertisement

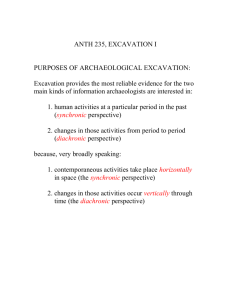

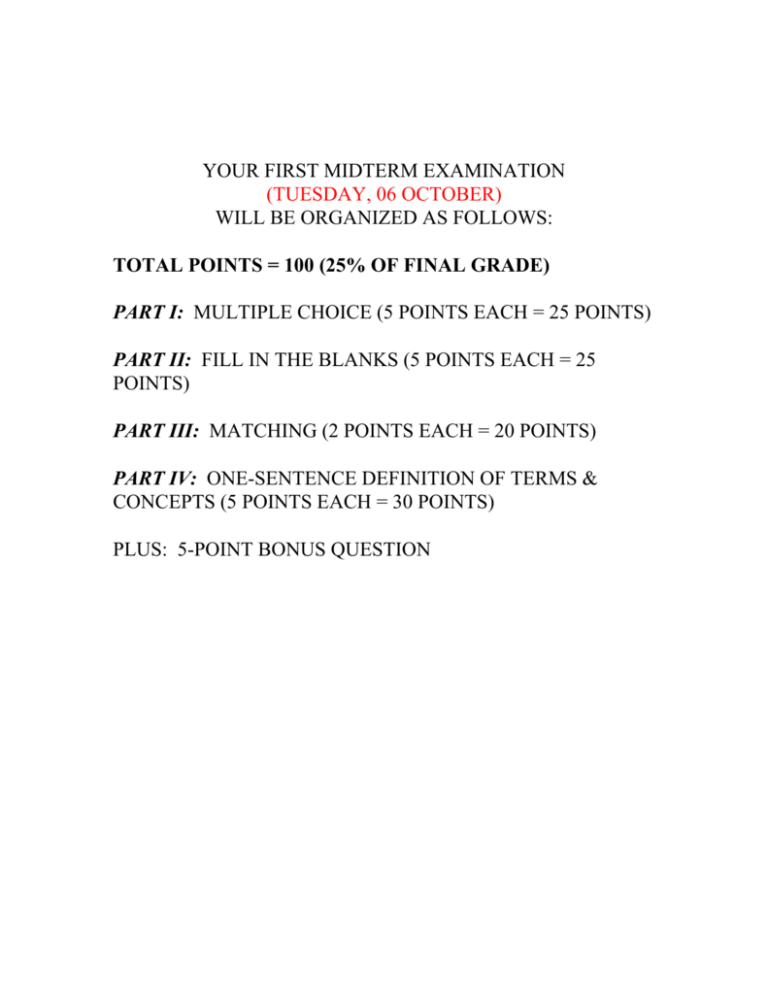

YOUR FIRST MIDTERM EXAMINATION (TUESDAY, 06 OCTOBER) WILL BE ORGANIZED AS FOLLOWS: TOTAL POINTS = 100 (25% OF FINAL GRADE) PART I: MULTIPLE CHOICE (5 POINTS EACH = 25 POINTS) PART II: FILL IN THE BLANKS (5 POINTS EACH = 25 POINTS) PART III: MATCHING (2 POINTS EACH = 20 POINTS) PART IV: ONE-SENTENCE DEFINITION OF TERMS & CONCEPTS (5 POINTS EACH = 30 POINTS) PLUS: 5-POINT BONUS QUESTION ANTH 235, EXCAVATION I PURPOSES OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION: Excavation provides the most reliable evidence for the two main kinds of information archaeologists are interested in: 1. human activities at a particular period in the past (synchronic perspective) 2. changes in those activities from period to period (diachronic perspective) because, very broadly speaking: 1. contemporaneous activities take place horizontally in space (the synchronic perspective) 2. changes in those activities occur vertically through time (the diachronic perspective) STRATIGRAPHY: One of the first steps in comprehending the great antiquity of humankind was the recognition by geologists of the process of stratification – that the Earth’s layers or strata (singular = stratum) are laid down, one on top of the other, according to processes that still continue today. (Charles Lyell’s concept of Uniformitarianism, first published in his Principles of Geology, 1833. Subtitle: “Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface by Reference to Causes Now in Operation”). The Law of Superposition: “where one geological or archaeological layer overlies another, the lower layer was deposited first.” There are exceptions such as reversed stratigraphy! The archaeological record is the ultimate nonrenewable resource! All excavation is an inherently and unavoidably destructive process! One can divide excavation techniques into two types: 1. Those that emphasize the vertical dimension by cutting into deep deposits to reveal stratification (below) 2. Those that emphasize the horizontal dimension by opening up large areas of a particular layer to reveal the spatial relationships between artifacts and features in that layer (sometimes called a clearing excavation) BRIEF RUN-THROUGH OF GENERALLY APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES OF EXCAVATION: Look first at the area to be dug. Figure out the best approach and tools needed before beginning. Don’t hurry! Be calm and purposeful. Feel the ground delicately. Test hardness of the soil with trowel – decide how excavation is to proceed. Loosen small amount of soil with trowel or other appropriate tool. Break up lumps and load into bucket (for transport to screens for further processing). Take earth out evenly throughout the excavation unit (2x2-meter square, etc.). Move away from the area dug; do not walk on newly excavated surfaces. Pay particular attention to changes in soil texture, color, and moisture. Maintain a level surface until a feature or floor level is encountered. Use a plumb bob to maintain vertical walls in the excavation unit. Never undercut excavation walls, even if a valuable object is projecting from it – undercutting makes interpretation of stratigraphy very difficult. All dirt removed should be screened and, if indicated, wet-sieved or floated. Establish the provenience of every object or feature in the stratum and record that position by a combination of photography and drafting. Bag or box artifacts from each stratum. Similar artifact classes (pottery, stone, bone, etc.) are usually bagged separately. When a new layer is reached, or anything unusual is encountered, STOP! Do not dig down into a new layer until all dirt and objects from the one above have been recorded, removed, and bagged. Avoid mixing artifacts from various levels! The depth of the top and bottom of each new level is measured from a standard position (called the datum point) and recorded in a field notebook. The field notebook should also contain a running commentary on the progress of the excavation – can be very stream-ofconsciousness, like a diary. Describe the soil of each new level carefully – color, texture, moisture, inclusions. Is it sterile (i.e., does not contain any artifacts)? When in doubt about how to proceed, STOP and discuss. Archaeological excavation is a group process. An example of why archaeological excavation must be a thoughtful, carefully considered process: The evolution of Troy at Hissarlik in western Turkey with the Homeric city indicated in red tint. (Illustration by Christoph Haussner) WHAT IS WORTH SAVING? Rule of thumb: “Unearth, record, remove, and preserve every visible artifact and feature.” The larger answer to this question has to do with sampling strategies. SPECIAL EXCAVATION CIRCUMSTANCES: BURIALS – Two important sources of data from burials: grave goods and the corpse itself. simple burial (a.k.a. primary burial): Placement of the body (both flesh and bones) in the ground or in some sort of coffin. May be in one of the following positions: extended flexed (leg bones bent less than 90) crouched (knees are bent up to the chin and hands rest under the chin – a.k.a. “the fetal position”) supine (body on its back) prone (body face down or, occasionally, resting on its side) multiple (more than one individual interred in a common grave) cremation: ritual disposal of the corpse by burning. Earliest evidence only ca. 5000 BCE. secondary burial: reburial of bones after flesh decomposes. Sometimes reburied as collective interments or ossuaries. monumental tombs: Egyptian pyramids, Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque, etc. Actually, a very rare form of interment. barrows or tumuli (singular tumulus): above-ground mounds of earth, stone, or a combination of the two intended to protect a grave chamber beneath. rock shelter and cave tombs: both formed naturally and often used as burial places by earlier cultures. UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGY – also a special circumstance involving particular excavation concerns. The focus is generally on shipwrecks – obviously, a synchronic event – so stratigraphy, per se, is not an issue. An interesting article that explores the current practical limits of underwater prehistoric archaeology using sonar and submersible robots: O’Shea, J. M. and G. R. Meadows. (2009). Evidence for early hunters beneath the Great Lakes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (June 23): 10120-10123. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS: The excavation process can be boiled down to three main phases: 1. identification of area(s) to be excavated 2. recovery and recording of the evidence 3. processing and classification of recovered materials Only when this process has been completed can the analytical aspects of archaeological inquiry begin in earnest... REMEMBER: “No amount of post facto computerized number crunching can compensate for poorly recorded field data. As the saying goes: ‘Garbage in, garbage out.’ Or, as more delicately stated by Philip Barker in 1977, ‘No statistical analysis…can be better than the quality of its data, the true reflection of the nature and distribution of the samples used in the analysis. Statistical analysis of material derived from partial and inadequately recorded excavations will inevitably be misleading, though unprovably so.’” (Stuart Fiedel in Discovering Archaeology, January/February 2000, page 46) Principal sources of archaeological excavating equipment: Archtools (http://www.archtools.co.uk/) Ben Meadows Company (http://www.benmeadows.com/) Forestry Suppliers (http://www.forestry-suppliers.com/) Miners (http://www.minerox.com/) Stoney Knoll Archaeological Supplies (http://www.stoneyknoll.com/) and, of course, (http://www.strati-concept.com/)