Making Modern World: The New Military History

advertisement

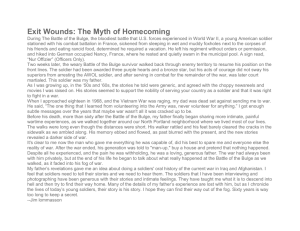

Making Modern World: The New Military History Introduction: Changes in the historiography of war Classical Roman writers – war history was an opportunity to promote certain political leaders virtues, or the qualities of the anonymous citizenry. 19th and early 20th Century historical writing was almost exclusively political history, of which wars and national achievement were key elements. Many national icons were warriors. Military History – a specialist subject much given to technological and arcane interests. Almost antiquarian. Often sanitized and a tidy approach to the description of war. Analyses limited to the performance of techniques, troop types, leaders and weapon systems. 1960s, the influence of Marxist and sociological thinking led to interest in ‘war and society’. E.g. civil-military relations (political), military reform, civilian experience in war, and class analyses of military hierarchy and the treatment of ‘ordinary ranks’. This affected military historians – John Keegan wanted to focus on the ‘face of battle’ – the actual experience of combat at the grass roots. The Face of Battle The Face of Battle unpicked accounts of Agincourt and the Somme and used eye witnesses from the lower ranks, and imagined reconstructions, to give a more ‘honest’ appraisal of what took place. He suggested there was far more confusion and error than the ‘official histories’ had claimed. Keegan’s contribution was to deconstruct texts (long before this became the fashionable post-modernist claim) to get at a new perspective. But Keegan’s approach was, in itself, not new. US Army Historical Teams Army historical Teams Interest was in how small groups fight once it was realized that men tend to fight for their immediate colleagues. Marshall’s findings are controversial. In Men Against Fire (1947), Marshall concluded: [quote] However, his results have been challenged. The reason why not all men discharge their weapons is because they don’t get a clear target. There is a higher ammunition expenditure because of the higher rates of fire but hit rates are small because targets are concealed or protected. It is not a case of men being reluctant to fight. Stephen Ambrose has created another myth: that democratic soldiers may enjoy a stronger cohesion and shared values than soldiers of totalitarian regimes. Studies of German forces in Russia appear NOT to support this, nor studies of soldiers in LDCs since 1960s. Cohesion and motivation are based on training, discipline, the ethos of the forces they belong to, exemplary junior officers, time in combat, and the conditions they face. For individuals, there are even more variables. Popular Cultural Representations of War The shift towards studies of individuals and small groups in combat (especially extended studies) have been reflected in Saving Private Ryan – the camera view taking the audience through the combat experience – and Band of Brothers. The representation is authentic and stands in contrast to film depictions of the 1940s-80s, including The Longest Day (D-Day) – although that film did narrate several factual vignettes. The impression given is that death is random. There is a frequent reference to pointless and poignant deaths, but a strong narrative of courage. The American troops, for all their flaws, are essentially good citizens who are ambassadors for their nation. But not all Americans, or soldiers, were involved in combat. Thousands of American, British and Empire troops were on garrison duty. Even in the Vietnam War, at the height of the American commitment, barely 30,000 were deployed on patrols or combat operations. What tends to be missing is the good humour that soldiers, sailors and airmen have in adversity. Not all soldiers are morose, waiting for death. In tough conditions, some make light of their problems. There is often spontaneous singing, joking and irony. Computer games try to recreate the experience of close quarter battle because it is thrilling. But it isn’t clear whether the gamers are trying to participate in the cinematic experience, or a fantasy. There is something disturbing about killing as entertainment, but that is what’s going on, and there are parallels with soldiers in combat: Some enjoy the sensation of hunting and killing, just as others are utterly repelled by it. Popular Culture There are other forms of popular culture which claim to represent war which we must briefly acknowledge: Re-enactors: Gives an impression of what an army might have looked like. Enthusiasts spend much time in attending to details of dress, weapons and accoutrements. However, they often lack the ‘atmosphere’ of the period, apply modern cultural norms (women in fighting units) and no-one is actually killed or maimed. Cannon balls would rip limbs from bodies. Some men at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 were wounded by fragments of bodies smashed by solid shot. Musket balls at close range would create large wounds, whilst slashing weapons like swords could render limbs and heads. You don’t see that at a family spectacular. Militaria Collectors: These are either weapon and uniform fetishists, or just harmless antiquarians who want to connect themselves with the past. Heroic War Films: Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone embodied the muscle-man, one-man army in a series of films in the 1980s. But historic films always tell you more about the period in which they were produced, rather than the period they are trying to convey. The 1980s were known for their brash, new affluence which spawned a new individualism on both sides of the Atlantic. The film Zulu was a classic because it tuned into a variety of older, folk history narratives – the beleaguered heroes, outnumbered and cut off, bravely defending a hopeless position, but defeating their opponents with honour. Courage is evident on both sides. The film-makers still felt compelled to alter the history, though, to suit modern conventions: Private Hook, a VC winner, was portrayed as a whisky swilling ne’er do well who ‘comes good’ under the pressure of combat – the real Hook was a tee-total Methodist and bearded ‘model’ soldier. The officers also express anti-war sentiments, criticizing the futility of war, when the real officers were supporters of an enterprise in empire building who were more anxious about their careers. More disturbing still is the popular obsession with the Vietnam War. This seems to have less to do with the fact that it was an American defeat (although they did not lose the fighting), than the morbid fascination with atrocities and soldierly indiscipline. The killing is almost ‘celebrated’. The films still tend to portray the Vietnamese as faceless, numberless masses whilst audiences are invited to ‘relate to’ the drugged, inebriated and shockingly violent American soldiers. Soldiers as Natural Born Killers Human nature? Environmental factors? (Do they start off as killers, or become killers because of the sights and experiences they are exposed to?) We might need to turn to anthropology for the answers, or perhaps to sociology, to contrast ‘social conditioning’ with ‘inherent behaviours’. The state certainly demands that men and women will exhibit certain characteristics: a defensive or offensive mentality, an awareness of threat or the opportunity for essential resources. Men enlist for a variety of reasons which can be arranged in different rank order, but they often include: Identification with a cause (a duty/obligation), Opportunism Pay Adventure To escape drudgery of civilian job/ unemployment or lifestyle To escape trouble at home (crime, girls) To advance a career Some argue, including Omer Bartov, that war brutalizes. He challenges the myth he believes has been created by German historians, namely that the Wehrmacht was generally opposed to Hitler. He suggests that Blitzkrieg, which brought military success between 1939 and 1942, was an icon to conceal the real business of ethnic killing. He believes that the radicalizing effects of killing in the war, especially on the Eastern Front, explains the Holocaust. He argues that the German troops were largely in favour of the killing. (Goldhagen, Browning, Friedlander too). Robert Jay Lifton, who studied the Nazi doctors who participated in the process of genocide, and who has also written on the cult-based killings of the Aum Shinri-kyo sect in Japan, and on war atrocities in Vietnam and Iraq (Crimes of War), is an expert in psychiatry. He believes that there is an automaton-like quality to killing, now even more enhanced by the long range weapon-systems like artillery, missile batteries, and aircraft. Many war veterans have spoken of their need to regard their enemy as a cipher, not as another human being with a family when fighting, but on reflection after combat, many have also spoken of the realization that ‘they’, the enemy, the Other, were just like them. Joanna Bourke believes, by contrast, there is an intimacy in killing. It’s ‘personal’ in the sense that infantrymen see the people they kill. She found that when soldiers had shot someone and killed them, some would still bayonet their victims to ‘make sure’ of the task, but also to connect with their opponent. Many took souvenirs from their victims as a marker or a talisman. She examined motivations particularly, and found that military training deliberately enhances aggression. This may be true, but much counter-insurgency training is also about restraint. Officer training, especially in Britain, appears to be much more ‘intellectual’, managerial and even paternalistic. Massacre in Warfare Irregular warfare a common aspect of the twentieth century – ‘partisans, guerrillas, insurgents, rebels’; Armies had to respond with counter-insurgency techniques. Why? The product of deep-seated feelings of nationalism, but a lack of the means to resist in a conventional stance. Wars of decolonization: again, asymmetrical (imbalance of forces) The usual format for internal wars of a state – (more next time) Counter-insurgency very hard to get right: irregular forces blend into the civilian population…. It is: Hard to distinguish them (physical appearance) The civilian population, or a portion of it, may be sympathetic to a rebel force. [EG – Kerala in Afghanistan, 1979; locals had been supplying the anti-communist/government resistance. 100s of men killed, bulldozed, house to house killings … and women fled to Pakistan. Dilemma: BUT why is it possible for men trained under conditions of strict discipline to become indiscriminate killers? Civilians are soft targets Can be ‘pressures’ to kill (once threshold is crossed, it is easily recrossed) Is there pleasure in killing? Some find the hunting aspect pleasing Is an expression of power – being able to outwit, and defeat an opponent; or to neutralize a threat For some, a moment of revenge – especially after the loss of popular friends and colleagues. (can result in the murder of those taken prisoner) But many more are revolted: Some men are physically sick Some are depressed, or more conscious of their own mortality as they reflect on the similiarity of their victims and themselves Some reject their service, others suppress memories. The tendency for massacre can also be countered and is not automatic. Good discipline An ethos that opposes killing civilians An affinity with the local population (EG: central Asian troops in the Soviet War in Afghanistan did not commit atrocities; British in Malaya referred to Malays as ‘friendlies’ and differentiated between them and their specific enemies – Chinese communists) Therefore, atrocities are ‘learned/conditioned behaviour’. Behaviours can be changed. What about the victims? Casualties of War Disease, not combat, was the biggest killer in war until c.1944. In 1918, war was also the vector for the spread of ‘Spanish ‘flu’. The condition probably originated in the crowded base areas of the Western Front, where foul, swine and men lived in close proximity. The movement of soldiers, especially those going and returning from leave, transmitted the disease to the civilian population, then into North America, Africa and South Asia. Strict quarantine and hygiene conditions imposed on troops of the British Indian Army halted the spread of flu’ in Mesopotamia (Iraq), but millions died globally. War and international deployments are a vector for the spread of new diseases such as HIV and Aids. Mugabe’s Zimbabwen troops who were dispatched to the DR Congo infected prostitutes and civilians there. Mugabe has also been accused of using aids as a biological weapon, encouraging troops to rape and infect women who sympathise with the democratic opposition to his rule. Casualties of war are not always killed. Usually there is a higher proportion of maimed. Fit, athletic young men who are rendered paraplegic also suffer from psychological trauma. For the second half twentieth century, the focus was on the potential deaths and injuries that would be sustained in the event of a nuclear exchange. Deaths would be caused by: Blast and fires Radiation sickness Possibly even a nuclear winter: climatic change caused by massive volumes of dust and debris in the atmosphere – blocking out sunlight, causing massive earth cooling, for years. The destruction of plant life – and therefore the food supply – would cause mass starvation. Casualties can be mental as well as physical Shell-shock and Battle fatigue The intensity and long periods of stress, from being exposed to danger, can cause changes in mental behaviour. First recognized in the ACW, few knew what had caused the trauma, or why some men suffered and others did not. The first sustained studies were carried out in the First World War. At first, it was thought that the close proximity of explosions could create pressure waves that led to lesions in the brain: hence ‘shell-shock’. Various treatments were attempted, from brutal electro-therapy to ‘talking cures’ (attempting to draw out the source of the trauma by mentally reliving it). The aim was to get the men back into action. Studies after the war, and during the Second World War, revealed that it was the duration of stress that was the most reliable guide to mental breakdown – hence ‘battle fatigue’. Lord Moran, a British officer, described men’s courage as an ‘account’. You could draw from it, but it had to be replenished in between these periods of acute stress. This could be done by carefully managed rotations, welfare arrangements (mail deliveries, home comforts) and good leadership to spot those at risk. The condition is still not fully understood. Everyone appears to have a different threshold of coping, based on one’s background and experience, and the unit they belong to (mates). Armies try to ‘inoculate’ their men and women with realistic training (helps!). Sufferers are best treated not by removing from the theatre of operations entirely (they get worse), but ‘proximity’ treatment – keeping them close to their parent unit and friends, engaged on ‘light duties’ to keep them occupied. Talking to professionals and the allocation of drugs can also assist recovery. New Military History embraces these aspects of the history of war – not just battles, weapons, maps and generals. There is also a social history Ports and garrison life are of considerable interest The lives of victuallers, civilians attached to the army/navy (wives, wallahs, prostitutes) There is an economic history – garrisons affects a local economy and offered new markets (Indian men as stencillers, nappy wallahs, and Dhobi-men). There is a cultural history too: Soldiers beliefs, ideas, vocabulary (crap hats, gat, bundoo, puttees, gonk, bimble, tab, yomp, GOPWOs, etc) Changes to fashion The media have long been interested in armies and heroes Wars are useful for propaganda purposes: tend to instil a sense of patriotic identity promote selflessness and sacrifice courage and nobility are celebrated Armies reinforce a sense of ‘place’ – the class system is usually replicated and emphasised in the military/naval hierarchy So how do we get at the ‘grass roots’ of New Military History? Sources for Experiential History [List] – but note the disparities between official history and reality (a tidying up exercise from the chaotic experience of fighting) Note also the need to bring in other branches of historical enquiry to military history, even other disciplines (sociology). Oral History/Memory This requires caution! Individual lived memory (‘worm’s eye view’) can be at odds with the historical collective memory. Do NOT assume that the individual is correct – they have a very narrow focus (‘worms can’t see very far’) Note that lived memory evolves over time (veterans begin to ‘make sense’ of their experiences and are affected by changes in what is acceptable. [EG Normandy veterans revisiting the battlefields had no idea of the big picture until I told them; German veterans now take a different view to the one they took in the 1940s!] Some repression of what’s painful/what one is ashamed of Culture of narration is stronger in some cultures than others – might also depend on victory or defeat Body language may offer a clue – ‘bearing’ might exude confidence but also dishonesty (an army cook in the Korean War gave the impression he was a combat soldier) The state can influence the ‘official memory’. Pierre Nora’s remembered realms or ‘sites of memory’ examined the monuments erected after the Great War in France to read their ‘message’. The memorialisation of war can be positive and negative: East of Ypres, the scene of continuous fighting from 1914-1918, there is an arresting ‘brooding soldier’ monument to the victims of the first gas attack in April 1915. Some villages at Verdun were never rebuilt – monuments to the destruction of the war; Ypres was rebuilt despite some requests that it too should remain in ruins as a sepulchre to British and Imperial casualties – took ten years. However, Lyn Macdonald notes in the introduction to To The Last Man: Spring 1918 that many First World War veterans were bewildered by the rewriting of the history of the Great War. In 1918, they regarded their achievement – the defeat of Germany as a triumph, but a growing anti-war sentiment from the late 1920s gave rise to a meta-narrative that the war had been a futile waste of life, that it was filled with horror (a word veterans did not use until after 1945) and was a constant bloodbath fought in deep mud. Veterans began to change their views to fit into this new narrative or trope. Andrew Corrigan has exploded this myth-making in Mud, Blood and Poppycock. He, like Jeremy Black, calls for a less emotional, more objective approach to this war, and all wars. War should be studied with the same objective analysis and rigour as any branch of history. Otherwise we risk falling into the trap of a new orthodoxy that wallows in emotive language but fails to tells us much about war in history.