cost-benefit analysis, incentives, and infrastructure

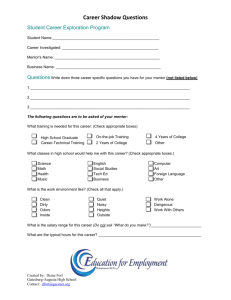

advertisement