HRM At Work: Student notes Chapter 6: Staffing and Resourcing the

advertisement

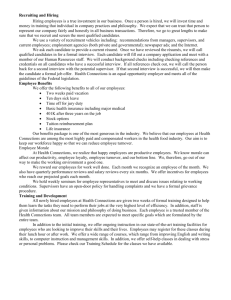

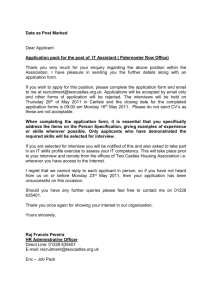

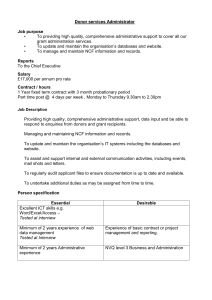

HRM At Work: Student notes Chapter 6: Staffing and Resourcing the Organisation Chapter overview This chapter introduces and discusses themes that are central to HRM. It offers an overview of human resource planning, as well as a more detailed description of, and analysis and advice on, the recruitment and selection process. The chapter reviews the recruitment and selection cycle in its entirety, from resource planning through to the selection decision. It emphasises the notion of cost-effectiveness as well as the links between resourcing and other aspects of HRM. The chapter begins with discussion of human resource planning, and the related topics of labour turnover and employee retention. After examining the view that planning is less relevant in a more chaotic competitive context, the chapter introduces four reasons why human resource planning is still important: it enables linkages between business and HR plans, it allows for better control of staffing costs, it enables organisations to create the right skills mix, and it allows for profiling of employees to meet equal opportunities criteria. The chapter then discusses three issues relating to hard HRP: forecasting future demand, forecasting internal supply, and forecasting external supply. Forecasting future demand can be done through objective or subjective measures. Forecasting internal supply involves discussion of how to calculate labour turnover, and two measures are described (the base rate of turnover, or wastage, and a more sensitive measure – the stability rate). Forecasting external supply involves discussion of the local labour market and national labour market. There then follows a discussion of job and role analysis, defined as ‘the process of collecting, analysing and setting out information about the content of jobs in order to provide the bases for a job description and data for recruitment, training, job evaluation and performance management’ (Armstrong, 1999). This leads to an examination of job descriptions, person specifications and competency frameworks, and the chapter then moves on to analyse recruitment methods. These are classified in four broad categories: internal recruitment (generally use of the internal labour market), closed searches (eg word-of-mouth recruitment, use of external contacts), the responsive approach (interviewing casual callers or former applicants, or placing notices outside factories or offices when there are vacancies), and open searches (advertising, use of the Internet). The discussion of selection methods does not cover the whole range of methods, choosing rather to analyse important criteria (practicability, sensitivity, reliability, validity) and focusing on two of the most commonly-used methods (different forms of interviews; selection testing – psychometric tests, personality tests), as well as introducing the idea that there are different ways of looking at the selection process – these four paradigms are: social exchange, scientific rationality, socialisation, and socially constructive reality. Chapter objectives After studying this chapter, you should be able to: undertake the main aspects of the recruitment and selection process implement, operate and evaluate cost-effective processes for recruiting and retaining the right calibre of staff in your own organisation contribute to the design, implementation and evaluation of selection decisions And you should understand and be able to explain: the links between human resource planning, recruitment and selection and other aspects of HRM the nature of the recruitment process and its principal components the major advantages and disadvantages of the most important selection methods, and their contribution to organisational effectiveness. Chapter outline HR planning, labour turnover and employee retention This section charts the decline of HR planning but proposes that it remains critically important, particularly given ongoing skills shortages and the rapidity of change, and an analysis of methods is presented. Job and role analysis The importance of accurate job and role analysis is examined in this section, together with analysis of methods in terms of sophistication, cost, convenience and acceptability. Job descriptions, person specifications and competency frameworks Each of these tools for recruitment and selection is evaluated. Recruitment methods The different methods used by employers to recruit are compared and contrasted. Closed searches, word of mouth, links to schools, etc, recruitment agencies, speculative applications, advertisements, JobCentre Plus are all means that are analysed. Choosing the best selection methods There is a wide range of methods used for selection. Here, the most common tools are evaluated in terms of accuracy in particular circumstances. These include interviews (traditional, structured, competency-based and telephone), tests (ability, literacy/numeracy, skills, online), questionnaires, and assessment centres. Differing paradigms of selection There is a range of competing definitions and paradigms in relation to selection, and three of them are considered in detail: social exchange, scientific rationality, and socially constructed reality. Conclusions Selection is all too often given too much focus in relation to the other processes involved in staffing and resourcing. However, all of the processes involved are important, and should be given equal weight. For example, without effective recruitment practices there would be a limited range of applicants. Feedback on mini-questions Do you believe HR planning is worthwhile in your organisation (or one with which you are familiar)? What do you see as the organisational benefits of spending time making plans about future employment projections? A shorthand way of thinking about human resource planning is that it is about getting the right people in the right place at the right time. What makes HR planning different from manpower planning or staffing is that the definition of ‘the right people’ incorporates the commonsense view that they should be appropriately trained, experienced and qualified, but goes further in saying that they should also be properly committed. So planning becomes more than an efficiency measure – ie getting the right numbers – it also involves considering effectiveness. If you subscribe to the idea that it is legitimate to think of people as resources, then planning how to deploy those resources is the most basic and the most important element of managing people. There are four main sets of reasons as to why it is worthwhile to carry out HR planning: it encourages links between HR plans and business strategy; it allows control over staffing costs; it enables employers to get the most beneficial mix of skills; and it allows for monitoring of equal opportunity initiatives. Examples of mismanaged HR planning is provided by some of the train-operating companies – some of which have been having to cancel one in every nine trains owing to a shortage of drivers, leading to fines of up to £2 million imposed by the rail regulator. To try to recruit more drivers they increased the salary for drivers dramatically so that other jobs (train managers) became relatively far worse-paid. This led to industrial action. You may well be able to cite other examples. Examine the set of figures above, as well as other data, and prepare a brief paper outlining the implications of this for the following: 1 a recruitment agency specialising in secretarial and administrative work 2 government departments overseeing the training of care workers and teachers 3 a careers adviser who is providing advice for school leavers or university graduates on future jobs. Answers to each in turn: 1 A large increase in demand is anticipated for secretarial and administrative work. This may be difficult to source from within organisations and, especially if demand for this kind of work is variable at organisational or departmental level, it probably makes sense to buy this in from an agency. There may be sense in trying to develop partnerships with some big employers so that the agency is seen as the employer of choice, and rates of pay and other conditions of employment may have to improve in order to secure loyal and committed staff. 2 Similar points arise in relation to this group of workers because demand is predicted to rise by approximately one million workers in each of these categories. But here there may be sense – given the fact that pay rates are set nationally – in trying to improve conditions locally and to get workers to identify with their local employer. Efforts may have to be made to recruit from overseas, although there is now increased activity by US employers to recruit teachers and health-care professionals who have been trained in the UK. This brings the question of training into sharper relief because there are concerns that highquality staff may be poached either by private-sector employers or by organisations based in other countries. 3 Decisions about future careers have to be made with a clear awareness of the future demand for jobs, and it is no good embarking on a career for which supply far outstrips demand without being fully informed about future opportunities. The data show a clear reduction in demand for a range of occupations – skilled workers, agricultural staff and various aspects of elementary work – and a rise in demand for caring/teaching and other professional, administrative and sales work. On the other hand, there is a danger that not enough people will be trained up to work in declining areas, so opportunities may actually be available in the short term. Of course, these figures are merely predictions, and they may be disrupted by major shocks to the system. Have labour turnover rates changed recently? What factors might help to explain this? What impact might this have on an organisation? You can find more information from CIPD or IRS surveys to update the figures quoted here. You may like to explore information on labour turnover within a particular industry or sector. As well as the two sources cited in the question, the Institute for Employment Studies carries out research in different industries. Alternatively, you may yourself have experience within a particular organisation where data on levels of turnover is available over time. The preceding paragraphs in the chapter outline two ways of theorising about labour turnover (economics school, and psychological school) and you should be able to adopt each of these theoretical approaches in explaining variations in turnover rates at an aggregated level. Perhaps the most convincing explanation would come in terms of the economic school – namely, that in times of relative prosperity, when the labour market is buoyant, alternative opportunities are plentiful and thus staff turnover increases. This is particularly so for public-sector workers because during times of economic prosperity one of the benefits traditionally associated with public-sector work – namely, job security – is less of an issue in choosing an employer. Explanations of higher rates of turnover can be derived from the psychological school, although these are likely to be more speculative and not to apply in all sectors. One example might be that there is now a revised social contract and, given the demise of such ideas as a job for life, overall levels of organisational commitment and loyalty are likely to be lower, thus people feel less normative or moral commitment – in simple terms, ‘The company won’t look after me, so I should look out for myself.’ This sits well alongside a growing body of evidence to suggest that traditional notions of career are outmoded in a context of greater employment ‘flexibility’. It is worth noting that the labour market or economic account may be better suited to explaining overall base rates of turnover, whereas psychological accounts may be better suited to understanding individuals’ decisions to leave in a particular context. Recently there has been considerable interest in the concept of employer branding (eg Martin and Beaumont, 2003; Suff, 2006a). Do a search from sources such as IRS Employment Review or People Management to find out more about this. Then, bearing in mind the factors listed above, make notes on what your organisation (or one with which you are familiar) might do to increase its attractiveness to job applicants. Employer branding is a concept that has become popular over the last few years, driven to a large extent by employers seeking high-quality employees in a tight labour market situation. It draws upon ideas from marketing where a close fit between the image of the firm and the type of workers employed is expected. At one level, this is hardly new, as students of psychology will know through the notion of person–organisation fit, or in HRM where some writers talk about alignment between organisational goals and worker commitment. The idea behind it is that there should be a link between mission statements, advertising, web pages, products, etc, such that the same message is being conveyed through each of these media. In some cases it could relate to firms which try to major on innovation, or fun at the workplace, or even corporate responsibility. Of course, branding does not stop the minute the individual joins the organisation, but has to be continually reinforced through induction, performance review, communications, and training and development. There is a danger too that branding can be portrayed as a neutral or positive concept, but you should be aware that there is also a darker side to the notion. This is the idea that branding is something that indicates who the person is employed by (much like branding cattle on a ranch), or that workers should always follow corporate goals without questioning their desirability or impact. Branding could be seen as an intrusion into people’s personal lives as well. Do job descriptions still exist in your organisation or one with which you are familiar? If detailed job descriptions still exist, how well do they work? If they have been abandoned, has it led to greater autonomy or greater stress? One way to approach this question is to consider what exactly is included in a job description. This should be: title, location, reporting requirements, responsibilities, purpose, terms and conditions, requirements (mobility, performance criteria) and miscellaneous duties. In one sense a level of detail in each of these areas is useful for potential employees to assess whether they wish to pursue that job. This is significant because a major cause of turnover is the unrealistic expectations of employees. Additionally, detail may delineate responsibilities and authority, and this can offer greater clarity in decision-making. On the other hand, having an overly specific and detailed job description is inconsistent with ideals of greater flexibility, empowerment, involvement or, more loosely, the idea that people should work ‘beyond contract’. Deciding whether or not detailed job descriptions are valuable would therefore involve an appreciation of the organisational culture and broader HR goals. For example, if the organisational culture and industry context suit ‘proactive problem-solving’ (eg a clientfacing role), this would seem consistent with broad-brush outlines of responsibilities rather than detailed job descriptions. By way of contrast, if the role entailed consistently following well-established procedures in order to ensure fairness (as is the case for many jobs in the civil service), then full detail may well be helpful – particularly for new incumbents who need carefully specified descriptions of duties and responsibilities. In either case, an inappropriate job description could cause stress. In the first instance where it was overly proscriptive, employees could feel hamstrung; in the second instance where it was insufficiently clear or ambiguous, employees could feel set adrift. Before moving on to the next part of this chapter, on competency frameworks, analyse the two plans in the box above in a little more detail. Focus in particular on the specifications that are used, explain what they are looking for and assess how easily and effectively these can be measured. What are the major shortcomings of these approaches? You are asked to consider the weaknesses of the person specification frameworks summarised. Clearly, there is a need to set criteria against which candidates may be measured, or the selection process is likely to be very difficult. Person specifications focus on the human attributes thought necessary to carry out the job, describing the kind of person considered to be successful in that job. The main criticism of traditional person specifications, however, is that they rely heavily on personal judgements of the human qualities associated with effective performance, and upon inferences about the personal qualities that might underpin behaviour. They are therefore not socially or politically neutral. Some of the categories used are also now dubious. Questions related to domestic commitments, mobility and family support, for example, as outlined in Rodger’s seven-point plan, are now likely to be considered unethical, inappropriate, and potentially discriminatory. Another disadvantage is that the requirements may be overstated, which can lead to difficulties in finding candidates, and may also mean that new recruits are dissatisfied when they find their talents are not used. Although person specifications are still widely used, it is likely to be in combination with competency-based frameworks that emphasise job competencies rather than personal qualities. These are discussed in more detail in the next section. After reading the information above, talk it through with your colleagues and friends, drawing on your own personal experience. Do you think that it makes commercial sense to focus so much on attitudes rather than technical skills? If you are annoyed about a product do you feel that your irritation can be overcome just because someone listens attentively to your complaint? Is it ethically or morally right that people should be excluded from jobs in a clothes shop on the basis of their looks or from a call centre on the basis of their accent? Consider these issues in relation to person specifications and competency frameworks. This question draws on research into ‘aesthetic labour’. However, selection based at least partly on how one looks or sounds is not new – hence the importance of first impressions in an interview situation, and the requirement in many European countries for a photograph to be attached to application forms. In many jobs appearance has always been important – for example, flight attendants or sales assistants in upmarket boutiques. Similarly, how one sounds has been central to the recruitment of many call centre personnel, with a preliminary telephone interview screening out candidates who are deemed not to have an appropriate telephone manner. The main point, however, is that there is a need for a combination of a suitable personality and technical skills. A well-spoken customer service agent must also have good product knowledge in order to answer queries successfully, because charming staff can only compensate for poor service so much. You may be able to discuss your own experiences of service encounters in airports and train stations, or unsatisfactory telephone calls with contact centre agents. You are asked also to discuss whether it is morally or ethically right that accent or appearance may be used as discriminating factors in the selection process. Is it right that a good candidate should be rejected on the basis of a strong regional accent or because he or she is overweight? In particular, there are arguments that it can lead to social exclusion of applicants deemed not to look or dress ‘right’, and there is the risk that this could mean that otherwise capable candidates from less privileged backgrounds may find it more difficult to secure certain types of employment. Debate with your colleagues the justification for employing ‘word-of-mouth’ recruitment methods. Consider both the performance and the ethical implications of this approach. As one of the pros (or ‘closed searchers’) you would emphasise the benefits of using this method. As one of the antis (or ‘open searchers’) you would point out the limitations of this method. The preceding paragraph in the chapter summarises both cases well, although you should be able to think of more reasons than are listed briefly here, particularly if you have in mind a particular organisation. In each camp there are performance and professional implications. Briefly, points for the pros are: the quality of candidates provided, cost, lowintensity selection, the likelihood of fit in terms of organisational culture and the likelihood of reinforcing organisational culture. Points for the antis are: such methods may lead to illegal and unethical practice, may stabilise organisational culture (thereby making implementing change more difficult), may exaggerate existing imbalances in race, gender and disability, may thwart attempts to manage diversity, and are likely to reduce variety within the organisation (diversity) leading to lower potential for creativity and original thinking. Whichever group you belong to, you could prepare a case perhaps in the form of a list of arguments. Representatives from pros and antis could then present their arguments in turn. It is likely that the use of e-recruitment is set to grow even more. Do you feel that this is positive trend? Now that you have read the text of this box, analyse the pros and cons of e-recruitment. IRS Employment Review and the CIPD’s People Management contain regular features on recruitment methods, including e-recruitment, and you should refer to the latest analysis. The main advantages and disadvantages of e-recruitment are set out in the box, but try to use your own experiences to contribute to this debate. You would no doubt agree that e-recruitment is a positive trend and one that will continue to expand as firms address the main disadvantages – and you might then wish to consider how those disadvantages can be overcome. Consider two interviews – one you think was well handled and one that was poorly handled – in which you have taken part, either as an interviewer or as an applicant. Describe the reasons for the differences between them. What can you learn from this to improve the validity of interviews as a selection device? It is likely that you have had experience of an interview process. Even if you are not currently working, you are likely to have undergone a selection process in which an interview was a key element – perhaps in the course of obtaining part-time work, or in applying to a university. Although it is difficult to separate the management of the interview from its final result, try not to rate how well the interview was handled on its outcome. In other words, you should not necessarily count an interview in which you were unsuccessful as one that was therefore poorly handled. Nor, of course, can you assume that because you might have performed poorly in an interview the interviewer was necessarily at fault. After all, a successful interview is commonly the result of both parties’ contributing effectively to the process, which implies that there is degree of responsibility with the interviewee as well as with the interviewer. This makes sense because candidates are selecting potential future employers just as the employer is selecting future employees. Interviews are often criticised for being unreliable, poor indicators of future success, and poor at discriminating between different candidates. This is not a function of the method or technique. The selection process is complex, and even the most sophisticated methods are far from perfect. Interviews are more likely to be successful if they are integrated with other methods, but also if they are properly planned and conducted by trained staff who are adequately prepared. Which selection techniques would you advise using for the appointment of 1 a worker in a call centre? 2 a chef in a busy restaurant? 3 a research scientist? Justify your answers. There is no right answer to this question. However, it is likely that using a particular combination of selection techniques will be more effective than choosing a candidate by chance or from a simple inspection of his/her CV. The criteria needed to assess the value of a single method of selection, or a battery of selection tests/methods, are fourfold: practicability (method has to be acceptable, cost-effective); sensitivity (ability to discriminate between candidates based on ability to do the job); reliability (would produce consistent results); and validity (the outcomes are a function of criteria relevant to the job). In terms of the three different occupations assessed above, it is likely that a potential call centre worker will be most effectively assessed by a simulation exercise (perhaps role-playing the part of the customer and testing his/her response), given that this will form the core part of the work. In the case of a chef, most people will be aware from watching TV programmes of the sort of work that this role entails. Clearly, technical skills are paramount, as is the ability to innovate as required. But there are also other skills needed – eg an ability to lead and inspire other team members, to work under extreme pressure and to be reliable. Traditional selection methods – such as an interview – would probably fail to draw out what is required. It would be much better to rely on reviews by critics of their previous restaurant work and an exercise in menu planning and delivery. Depending on the nature of the work (project-based, working alone), it may be comparatively easy to select a research scientist, even though he/she is likely to be doing the most complicated work. This is because there will already be clear performance indicators, and a good indicator of the kind of work this person has done in the past – eg relevant publications, conferences. This information can be obtained by reading the CV. It should certainly be easier to tell even from a cursory interview whether a candidate in this post knew what he/she was talking about, provided that the interview was conducted by a fellow research scientist. Can selection decisions ever be truly objective tests of a person’s suitability for employment? This is a somewhat philosophical question that if you are not careful may prompt a rather discursive answer. Try to bear in mind that even when people strive to remain ‘scientific’, or impartial, bias can insinuate itself at many stages in even the most technically sophisticated selection process. It is perhaps easier to say what kind of selection processes would not be objective than it is to say what type of process would be truly objective. For example, if managers select on the basis of one interview because they believe they are a good judge of character, that is highly subjective. Whenever a process involves judgement, it can be said to rest on opinion, and it will in some sense be subjective. What makes the case of a person selecting because ‘she/he is a good judge of character’ the epitome of subjectivity is that it is one person’s judgement, only one method is being used, the selection criterion is vague or impossible to define, and candidates have no idea what is expected of them. Presumably, then, more objective selection (that still allows for judgement) would involve more than one person (multirater), more than one method, with clear criteria and a more transparent process. It is worth mentioning that even completely objective methods can be unfair where they bear no relation to the ability to do the job. For example, where a selection criterion for doing a job was ‘candidates must be over 35’, this might be objective and transparent – although it would not be fair if age were irrelevant to doing the job.