rise of national monarchies

advertisement

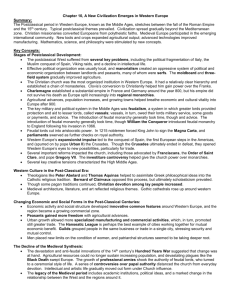

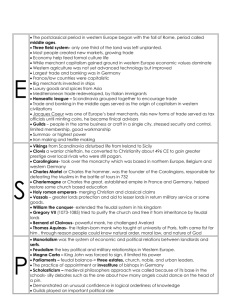

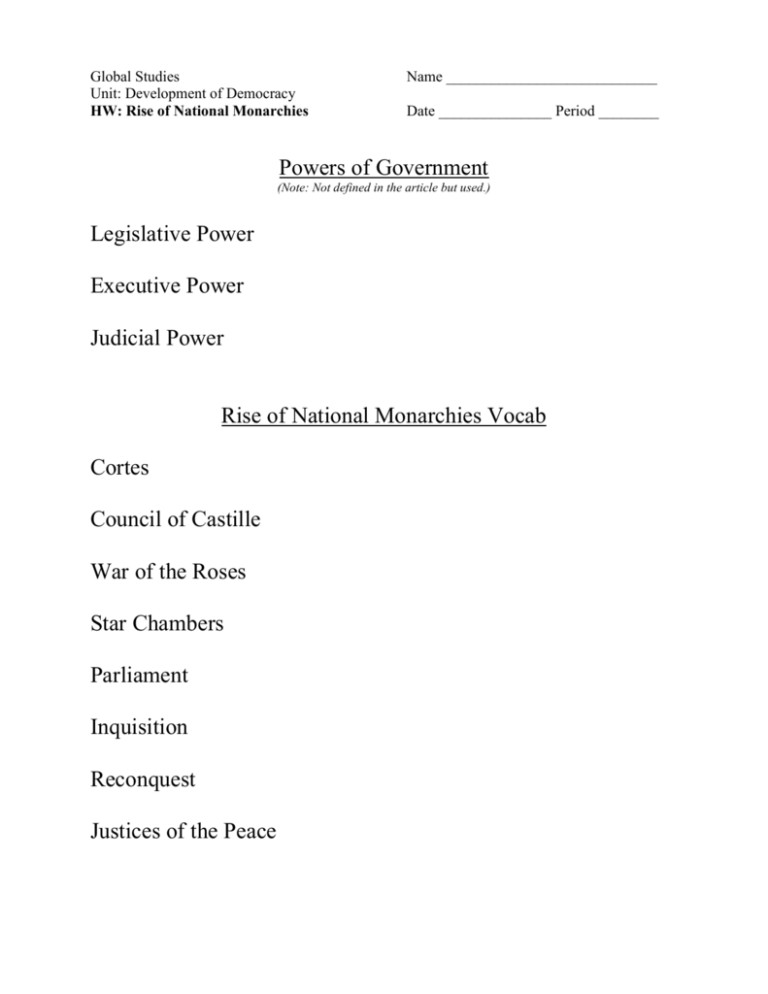

Global Studies Unit: Development of Democracy HW: Rise of National Monarchies Name ____________________________ Date _______________ Period ________ Powers of Government (Note: Not defined in the article but used.) Legislative Power Executive Power Judicial Power Rise of National Monarchies Vocab Cortes Council of Castille War of the Roses Star Chambers Parliament Inquisition Reconquest Justices of the Peace The Rise of National Monarchies The modern nation is a recent phenomenon that began to emerge only a few hundred years ago. To understand this development, we must look to Europe of the Middle Ages, a time when there were no national governments and no national leaders. Instead, regionalism was a dominant factor in life. Why? There are several reasons. Communications were nonexistent, and transportation facilities were poor. People of one area had almost no contact with people only a few miles away. Also, most regions were under the control of feudal lords, and the official ruler of the kingdom was only as strong as the lords allowed him to be. The kings had to rely on the lords for their revenues (money) and for their military strength-- and the feudal lords sought to prevent the kings from assuming too much power. Finally, the Catholic Church was a pervasive element in life—a person’s ultimate loyalty was to the church and the pope, not to a king. But this was changing in the later Middle Ages. Trade, which had begun to increase after the Crusades, was increasing in volume, and the contacts it created between people were breaking down the barriers of regionalism. The middle class emerged and became a wealthy and influential force in the cities, challenging the position of feudal lords. The intellectual awakening of the Renaissance was beginning, and many new ideas disagreed with the teachings of the church. It was in this period of change and confusion that the first national monarchies arose in France, England, and Spain. The kings in these countries sought to put everyone in the state under their control. Their methods were often brutal. The statement that “the ends justify the means” was used to support their brutality. These rulers won the support of powerful merchants in the cities. These merchants, like the kings, wanted to weaken the strength of the feudal lords. The strong monarchies that emerged would form the basis of government for generations. France Charles II, king of France began the task building the French state and increasing the power of the French monarchy. He set about to free himself from reliance on the feudal lords. He established a permanent royal army. And he sought new sources of revenue. One of these sources was the church. Charles limited the power of the pope in Catholic France by taking over control of tithes and appointing church leaders. Some of the money that used to flow to Rome now enriched the royal treasury. But Charles II was unable to overcome the power of the feudal lords. During his reign, large areas of France were still outside his control, ruled by men who defied the authority of the king. It was Charles’ son Louis XI who finally subdued the feudal lords and established himself as the first national monarch in Western Europe. He did so with the support of most of his subjects. Louis, a crafty and devious ruler, was called the “universal spider” because he skillfully trapped his victims—his opponents—and disposed of them. He forced his subjects to pay him higher taxes, but he softened the blow by creating positions in his government to be granted to those who were loyal to the king. Thus he won even the strongest protestors over to his side. Louis enlarged the royal army, but he limited its use to times of real national emergency. During his 22-year reign, he hired many of the feudal lords and brought their territory under royal control. The feudal territories would ALL have to be brought under the royal domain if Louis were to ensure his control. The strongest was the duchy of Burgundy, comprising what is now Belgium, Holland, and Northern France. Charles the Rash, sometimes called Charles the Bold, was the ruler of Burgundy. If Louis XI were to succeed as a ruler, and establish control over all the feudal lords, he would have to subdue Charles the Rash. But Louis couldn’t risk defeat at the hand of his chief rival, and so he subsidized a Swiss army to attack Burgundy. The Swiss went to war willingly, and on three occasions defeated the Burgundian forces. Charles the Rash was killed in the last of these battles, and, as he left no male heirs, his territory was divided. The duchy of Burgundy was added to the royal holdings of Louis XI. The king of France was finally assured of his authority over the feudal lords—he had proved his strength to them. Great Britain In England, the growth of the national monarchy developed later than in France. England had no immensely powerful feudal lords near the end of the fifteenth century, but there was a council of nobles who, by tradition and law, advised the king. This council was called Parliament. The War of the Roses, a civil war fought between two noble families, raged throughout England for thirty years. During that time, most of the powerful lords were either killed, or their fortunes depleted. In 1485, King Richard III was defeated by Henry Tudor, who became king. The War of the Roses had ended. Henry Tudor was confirmed as King Henry VII by Parliament. He unified England under his rule and strengthened the bonds that tied his subjects to him. Henry married Elizabeth of York, who was a member of Richard III’s family, and thus ended the conflict that had split England into two warring sides. Moreover, he dealt firmly with those who threatened his position, but he kept men loyal to him with the unspoken promise of future favors. Only Parliament was empowered to approve new taxes, and its members hoped to gain power over the king in other matters, too. But Henry called Parliament only when he could not find other sources of revenue; it met only seven times in his 24 year reign. On the local level, government was changing, too. Henry increased the duties of the justices of the peace, and made these local executives directly responsible to him. For the first time, the position became an honorable and attractive one. A special court, known as the Star Chamber, enforced the royal will. Henry was careful not to let it interfere with the older common law courts. For the most part, the English people approved. Yet, in this time period, there were two distinct laws: the King’s law, and the church law. Henry, like Louis XI, sought to control the church by appointing one of strongest supporters, a lawyer named Morton, to be archbishop of Canterbury. And the crown used the church to build up its strength and reputation. Henry doubled royal revenue when the archbishop agreed to contribute church tithes to the royal treasury. Thus, Henry seldom had to call upon Parliament to raise taxes, a fact greatly appreciated by his subjects. Henry VII also won the support of businessmen, thanks to his shrewd commercial policies. The king sought to make England a commercial power. England was an important producer of wool and wool cloth, but at the time of Henry VII, the country didn’t have the ships or the finances to control exports. So, English merchants couldn’t compete with the Italians who carried the bulk of English foreign trade, and had long been granted special privileges. Henry VII gained guarantees for English merchants abroad by threatening to take back these privileges. He made a number of commercial treaties which strengthened the power of the English merchants. All in all, England was rapidly becoming a financial success. And when Henry VII died in 1509, he left behind a prosperous and orderly country, a country in which the vast majority of the people supported the monarchy, a country destined to become one of the most powerful in the world in the course of the 16th century. Spain To understand the Spanish story we have to look back several hundred years. In the eighth century, Muslims from North Africa began invading Spain, and by 910 they had conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula, leaving only the tiny kingdoms of Leon and Navarre and the county of Barcelona in the north in the hands of Spanish rulers. The succeeding centuries of warfare are known as the Reconquest, during which Christian princes drove the Muslims southward and established small feudal states throughout the peninsula. It was a disjointed effort. There were long periods of peace, and Christian states often fought each other rather than the enemy, but eventually the Muslims were contained in the kingdom of Grenada, where they held out until 1492. By the middle of the 14th century, three kingdoms dominated the peninsula: Castille, Portugal, and Aragon. Portugal had won its independence in the 12th century. Castille, the leader of the Reconquest, became the largest and most populous kingdom on the peninsula. Aragon had grown out of the county of Barcelona, and was a strong Mediterranean power with interests in Italy and France. But in both Aragon and Castille, the power of the monarchy was limited by the power of the local nobility and by the Cortes, Spain’s legislature, which had to be called every two years. Before a national monarchy could be established in Spain, national unity had to be achieved. The first step occurred when Prince Ferdinand of Aragon married Princess Isabella of Castille. Together, Ferdinand and Isabella raised Spain to the rank of the most powerful nation in Europe. They did so through their power in the two kingdoms. Creating strong government was, for the most part, the work of the Queen. Isabella was to become an absolute monarch, firm in the belief that her power as a ruler was God-given. The first task was to drive the Muslims from Spain, and the Muslim kingdom of Grenada finally surrendered in 1492, the same year that Columbus sailed to America and claimed its vast territories for Isabella. The queen also sought to control the nobility, the Cortes, and the local town government. She called the Cortes infrequently, and formed a “Council of Castille” whose members she appointed. The council was given executive power, subject, of course, to the power of the queen. Isabella also allied herself with owners of industry and businessmen, the economically powerful people of her kingdom, who resented the power of the nobles and sought advancement for themselves. Most important, she allied herself with the church, which became a powerful weapon. The pope gave the Spanish rulers virtual control over the Catholic Church in all their lands. Under Isabella, the office of the Inquisition was introduced. The Spanish Inquisition was a church court. It was a tool of royal power, more political than religious in nature. Its purpose was to try, convict and punish known heretics. The primary targets of the Inquisition were the Muslims and the Jews. Isabella used the Inquisition for her own political power by accusing many innocent people of heresy. Thus, by the beginning of the 16th century, national monarchies were well-established in three Western European countries: England, France, and Spain. The face of Europe had changed, as trade brought people together and broke down medieval regionalism, as the power of church and pope was weakened, as kings brought people together under one rule. A political renaissance was under way in Western Europe, and the ground was laid for colonial expansion of the national monarchies, and for the transfer of European institutions and ideas to America. Global Studies 10 Unit: Europe Rise of National Monarchies Questions: 1. In general: During the early Middle Ages, what barriers prevented kings from governing a clearly defined country? 2. In general: What characteristics of the modernizing medieval society fostered or promoted the development of strong national monarchies? FRANCE 1. What two kings helped create the strong monarchy in France? 2. How did the monarchy gain power from the church? 3. How did the monarchy gain power from the nobles? GREAT BRITAIN 1. What king was most responsible for gaining power for the monarchy? 2. How did the monarchy gain power from the nobility? 2.1. Magna Carta 2.2. The War of the Roses 2.3. Parliament 2.4. Creating the position of justice of the peace 3. How did the monarchy gain power from the church? 3.1. Star Chamber 3.2. The appointment of the archbishop of Canterbury 4. How and why did the middle class help the kings? SPAIN 1. Who was responsible for creating a strong monarchy in Spain? 2. How did the monarchy use religious issues to gain power? 2.1 Muslims 2.2 Christian Church 3 How did the monarchy gain power from the nobles? 3.1 The Cortes 4 How did the middle class help the monarchy gain power? Global Studies 10 Unit: Europe Venn Diagram: Rise of Monarchies Name ______________________________ Date _____________ Period ____________ DIRECTIONS: Use the Venn diagram to compare and contrast the centralization of power in Britain, France and Spain. Then write a conclusion. FRANCE SPAIN CONCLUSION: GREAT BRITAIN