An adjectival phrase (AP) is a phrase with an adjective as its head (e

advertisement

Adjectival phrase

An adjectival phrase (AP) is a phrase with an adjective as its head (e.g.,

full of toys). Adjectival phrases may occur as postmodifiers to a noun (a bin

full of toys), or as predicatives (predicate adjectives) to a verb (the bin is

full of toys).

Adjectival phrases give more detail to a noun. They can become arbitrarily

long, and in some languages they tend to become quite complex.

Examples

red (rose)

red, big (rose)

red, big, reminding me of my former love (rose)

red, big, filling my senses with sorrow, reminding me of my former love

(rose)

An adverbial phrase is a linguistic term for a phrase with an adverb as

head. The term is used in syntax.

Adverbial phrases can consist of a single adverb or more than one. Extra

adverbs are called intensifiers. An adverbial phrase can modify a verb

phrase, an adjectival phrase or an entire clause.

Examples of adverbial phrases in English:

oddly enough

very nicely

quickly

Adverbial function

Other syntactic phrase types can also function adverbially, like the

prepositional and verb participle phrases below:

in a happy way

happily working

having found the road to happiness

A NOUN PHRASE

A noun phrase is either a single noun or a pronoun as the subject

or object of a verb.

EG: The people that I saw coming in the building at nine o'clock

have just left.

('The people ... nine o'clock' is a lengthy noun phrase, but it

functions as the subject of the main verb 'have just left'.)

Transitive verb

In syntax, a transitive verb is a verb that requires both a subject and one

or more objects. Some examples of sentences with transitive verbs:

Kyle sees Adam. (Adam is the direct object of "sees")

You lifted the bag. (bag is the direct object of "lifted")

I punished you. (you is the direct object of "punished")

I give you the book. (book is the direct object of "give" and "you" is the

indirect object of "give")

Verbs that don't require an object are called intransitive, for example the

verb to sleep. Since you cannot "sleep" something, the verb acts

intransitively. Verbs that can be used in a transitive or intransitive way are

called ambitransitive; an example is the verb eat, since the sentences I am

eating (with an intransitive form) and I am eating an apple (with a transitive

form that has an apple as the object) are both grammatically correct.

1) The meeting is at 2:30.

a) The meeting = subject

b) is = copular verb

c) at 2.30 = adverbial of time (form = prepositional phrase)

2) She is ahead of her fellow students.

a) She = subject

b) is = copular verb

c) ahead of her fellow students = complement

(form = adjectival prepositional phrase)

3) We should look ahead.

a) We = subject

b) should look = transitive

c) ahead = adverbial of place (form = adverb)

4) We parted good friends.

a) We = subject

b) parted = copular verb (YES, INTERESTING.)

c) good friends = subject complement (form = noun phrase)

5) Norma is in good health (NOT 'SEEMS TO BE', BUT

ACTUALLY 'IS')

a) Norma = subject

b) is = copular verb

c) in good health = subject complement

(prepositional phrase that acts as an adjective)

6) Pat is in a bad mood (NOT 'SEEMS TO BE', BUT ACTUALLY

'IS')

a) Pat = subject

b) is= copular verb

c) in a bad mood = subject complement

(prepositional phrase that acts as an adjective)

7) The dog smelled hungrily at the package.

a) the dog = subject

b) smelled at = transitive verb

c) the package = direct object

d) hungrily = adverbial of manner

8 ) She managed to keep her children off cigarettes.

a) she = subject

b) managed = transitive verb

c) to keep her children off cigarettes = object of 'managed'

d) her children = indirect object of 'keep off'

e) cigarettes = direct object of 'keep off'

9) The animals were feasting on lots of good food.

a) The animals = subject

b) were feasting on = transitive verb

c) lots of good food = direct object (form = noun phrase)

THIS CAN EQUALLY WELL BE DIAGRAMMED AS:

b) were feasting = transitive verb

c) on lots of good food = direct object (form = prepositonal

phrase)

The Structure of a Sentence

Remember that every clause is, in a sense, a miniature sentence. A simple

sentences contains only a single clause, while a compound sentence, a complex

sentence, or a compound-complex sentence contains at least two clauses.

The Simple Sentence

The most basic type of sentence is the simple sentence, which contains only

one clause. A simple sentence can be as short as one word:

Run!

Usually, however, the sentence has a subject as well as a predicate and both the

subject and the predicate may have modifiers. All of the following are simple

sentences, because each contains only one clause:

Melt!

Ice melts.

The ice melts quickly.

The ice on the river melts quickly under the warm March sun.

Lying exposed without its blanket of snow, the ice on the river melts quickly

under the warm March sun.

As you can see, a simple sentence can be quite long -- it is a mistake to think

that you can tell a simple sentence from a compound sentence or a complex

sentence simply by its length.

The most natural sentence structure is the simple sentence: it is the first kind

which children learn to speak, and it remains by far the most common sentence

in the spoken language of people of all ages. In written work, simple sentences

can be very effective for grabbing a reader's attention or for summing up an

argument, but you have to use them with care: too many simple sentences can

make your writing seem childish.

When you do use simple sentences, you should add transitional phrases to

connect them to the surrounding sentences.

The Compound Sentence

A compound sentence consists of two or more independent clauses (or simple

sentences) joined by co-ordinating conjunctions like "and," "but," and "or":

Simple

Canada is a rich country.

Simple

Still, it has many poor people.

Compound

Canada is a rich country, but still it has many poor people.

Compound sentences are very natural for English speakers -- small children learn

to use them early on to connect their ideas and to avoid pausing (and allowing an

adult to interrupt):

Today at school Mr. Moore brought in his pet rabbit, and he showed it to the

class, and I got to pet it, and Kate held it, and we coloured pictures of it, and it

ate part of my carrot at lunch, and ...

Of course, this is an extreme example, but if you over-use compound sentences

in written work, your writing might seem immature.

A compound sentence is most effective when you use it to create a sense of

balance or contrast between two (or more) equally-important pieces of

information:

Montéal has better clubs, but Toronto has better cinemas.

Special Cases of Compound Sentences

There are two special types of compound sentences which you might want to

note. First, rather than joining two simple sentences together, a co-ordinating

conjunction sometimes joins two complex sentences, or one simple sentence and

one complex sentence. In this case, the sentence is called a compoundcomplex sentence:

compound-complex

The package arrived in the morning, but the courier left before I could

check the contents.

The second special case involves punctuation. It is possible to join two originally

separate sentences into a compound sentence using a semicolon instead of a coordinating conjunction:

Sir John A. Macdonald had a serious drinking problem; when sober,

however, he could be a formidable foe in the House of Commons.

Usually, a conjunctive adverb like "however" or "consequently" will appear near

the beginning of the second part, but it is not required:

The sun rises in the east; it sets in the west.

The Complex Sentence

A complex sentence contains one independent clause and at least one

dependent clause. Unlike a compound sentence, however, a complex sentence

contains clauses which are not equal. Consider the following examples:

Simple

My friend invited me to a party. I do not want to go.

Compound

My friend invited me to a party, but I do not want to go.

Complex

Although my friend invited me to a party, I do not want to go.

In the first example, there are two separate simple sentences: "My friend invited

me to a party" and "I do not want to go." The second example joins them

together into a single sentence with the co-ordinating conjunction "but," but both

parts could still stand as independent sentences -- they are entirely equal, and

the reader cannot tell which is most important. In the third example, however,

the sentence has changed quite a bit: the first clause, "Although my friend invited

me to a party," has become incomplete, or a dependent clause.

A complex sentence is very different from a simple sentence or a compound

sentence because it makes clear which ideas are most important. When you write

My friend invited me to a party. I do not want to go.

or even

My friend invited me to a party, but I do not want to go

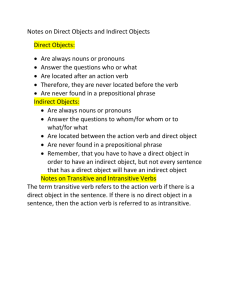

QuickTime™ and a

TIFF (Uncompressed) decompressor

are needed to see this picture.

It's actually pretty straightforward. The majority of the time you

use affect with an a as a verb and effect with an e as a noun.

Affect with an a means "to influence," as in, "The arrows

affected the aardvark," or "The rain affected Amy's hairdo." Affect

can also mean, roughly, "to act in a way that you don't feel," as in,

"She affected an air of superiority."

Effect with an e has a lot of subtle meanings as a noun, but to me

the meaning "a result" seems to be at the core of all the definitions.

For example, you can say, "The effect was eye-popping," or "The

sound effects were amazing," or "The rain had no effect on Amy's

hairdo," or "The trick-or-treaters hid behind the bushes for effect."