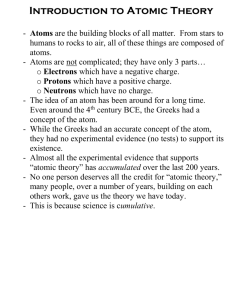

Introduction to Nanoscience

advertisement

Introduction to Nanoscience Nanoscience is the study of phenomena on a nanometer scale. Atoms are a few tenths of a nanometer in diameter and molecules are typically a few nanometers in size. The smallest structures humans have made have dimensions of a few nanometers and the smallest structures we will ever make will have the dimensions of a few nanometers. This is because as soon as a few atoms are placed next to each other, the resulting structure is a few nanometers in size. One of the first people to point out potential benefits of making devices at the nanoscale was Richard Feynman. In a speech he gave in 1959 entitled, There's plenty of room at the bottom, Feynman talked about "the problem of manipulating and controlling things on a small scale." He estimated that it should be possible to reduce the printing on a page by a factor of 25000 and if that were done, all the books ever printed could be copied in a space of about 35 ordinary pages. Feynman also speculated about moving individual atoms around. Here's what he had to say about rearranging atoms. Rearranging the atoms But I am not afraid to consider the final question as to whether, ultimately---in the great future---we can arrange the atoms the way we want; the very atoms, all the way down! What would happen if we could arrange the atoms one by one the way we want them (within reason, of course; you can't put them so that they are chemically unstable, for example). Richard Feynman There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom. Up to now, we have been content to dig in the ground to find minerals. We heat them and we do things on a large scale with them, and we hope to get a pure substance with just so much impurity, and so on. But we must always accept some atomic arrangement that nature gives us. We haven't got anything, say, with a "checkerboard" arrangement, with the impurity atoms exactly arranged 1,000 angstroms apart, or in some other particular pattern. What could we do with layered structures with just the right layers? What would the properties of materials be if we could really arrange the atoms the way we want them? They would be very interesting to investigate theoretically. I can't see exactly what would happen, but I can hardly doubt that when we have some control of the arrangement of things on a small scale we will get an enormously greater range of possible properties that substances can have, and of different things that we can do. In 1960 Feynman thought that in the great future we would be able to arrange atoms the way we want. This is now possible for some kinds of atoms on some kinds of surfaces. Below are two images of atomic scale structures made in Don Eigler's lab at IBM. A scanning tunneling microscope (STM) was used to push atoms and molecules around on a metal surface to make these structures. 1 Fig. 1.1. On the left, iron atoms where arranged on a copper surface to make the kanji character for "atom". On the right is Carbon Monoxide Man consisting of carbon monoxide molecules on a platinum surface. Not every possible arrangement of atoms can be made this way but technology is moving in the direction that Feynman predicted. Fig. 1.2. Researchers at IBM made a logic circuit based on the motion of carbon dioxide molecules on a copper surface. This device is a three input sorter. The left image was made by a scanning tunneling microscope and on the right is the design of the circuit showing the placement of all of the atoms. Reference: IBM molecule cascade website. K. Eric Drexler is another person who has considered constructing devices atom by atom. In two influential books, Engines of Creation, and Unbounding the Future: the Nanotechnology Revolution he described devices called assemblers that could be used to assemble atoms and molecules into larger structures. He thought that the first generation of assemblers would 2 resemble enzymes. Enzymes are catalysts that are often made from proteins. Drexler believes that in the future, it will be possible to make universal assemblers. These are assemblers that can be programmed to construct any stable atomic structure. Here is an excerpt from Drexler's book. Universal assemblers These second-generation nanomachines - built of more than just proteins - will do all that proteins can do, and more. In particular, some will serve as improved devices for assembling molecular structures. Able to tolerate acid or vacuum, freezing or baking, depending on design, enzyme-like second-generation machines will be able to use as "tools" almost any of the reactive molecules used by chemists - but they will wield them with the precision of programmed machines. They will be able to bond atoms together in virtually any stable pattern, adding a few at a time to the surface of a workpiece until a complex structure is complete. Think of such nanomachines as assemblers. K. Eric Drexler Engines of Creation. Because assemblers will let us place atoms in almost any reasonable arrangement (as discussed in the Notes), they will let us build almost anything that the laws of nature allow to exist. In particular, they will let us build almost anything we can design - including more assemblers. The consequences of this will be profound, because our crude tools have let us explore only a small part of the range of possibilities that natural law permits. Assemblers will open a world of new technologies. Advances in the technologies of medicine, space, computation, and production - and warfare - all depend on our ability to arrange atoms. With assemblers, we will be able to remake our world or destroy it. So at this point it seems wise to step back and look at the prospect as clearly as we can, so we can be sure that assemblers and nanotechnology are not a mere futurological mirage. Building devices atom by atom like this is called molecular nanotechnology. Not everyone agrees that it will be possible to build a universal assembler. Some people consider Drexler's book more science fiction than science. It has stimulated a lively debate about what is possible with nanotechnology. Drexler wrote that aging could be stopped or reversed using nanotechnology. Some people have had their heads frozen after they die so that they can be reanimated by nanotechnology in the future. This has given nanotechnology the reputation of sometimes being a bit wacky. However, it is interesting to speculate on what could be possible. Another nanotechnology visionary is who has stimulated much debate is Ralph Merkle. Here's an excerpt from one of his articles. It's a small, small, small, small world Ralph Merkle It's a small, small, small, small world. Manufactured products are made from atoms. The properties of those products depend on how those atoms are arranged. If we rearrange the atoms in coal, we get diamonds. If we rearrange the atoms in sand (and add a pinch of impurities) we get computer chips. If we rearrange the atoms in dirt, water and air we get grass. Since we first made stone tools and flint knives we have been arranging atoms in great thundering statistical heards by casting, milling, grinding, 3 chipping and the like. We've gotten better at it: we can make more things at lower cost and greater precision than ever before. But at the molecular scale we're still making great ungainly heaps and untidy piles of atoms. That's changing. In special cases we can already arrange atoms and molecules exactly as we want. Theoretical analyses make it clear we can do a lot more. Eventually, we should be able to arrange and rearrange atoms and molecules much as we might arrange LEGO blocks. In not too many decades we should have a manufacturing technology able to: 1. Build products with almost every atom in the right place. 2. Do so inexpensively. 3. Make most arrangements of atoms consistent with physical law. ... What would it mean if we could inexpensively make things with every atom in the right place? For starters, we could continue the revolution in computer hardware right down to molecular gates and wires -- something that today's lithographic methods (used to make computer chips) could never hope to do. We could inexpensively make very strong and very light materials: shatterproof diamond in precisely the shapes we want, by the ton, and over fifty times lighter than steel of the same strength. We could make a Cadillac that weighed fifty kilograms, or a full-sized sofa you could pick up with one hand. We could make surgical instruments of such precision and deftness that they could operate on the cells and even molecules from which we are made -- something well beyond today's medical technology. The list goes on -- almost any manufactured product could be improved, often by orders of magnitude. We can't yet build most of the nanomachines that are being discussed but they can be simulated on a computer. Figure 1.3 shows a computer simulation of a nanoscale bearing that was designed by Ralph Merkle. Using simulations, it is possible to test a nanomachine and see if it would work the way it was designed to work. More information on the bearing simulation can be found on the Zyvex website. Fig. 1.3. A simulation of a nanoscale bearing. Nanoscience in physics, chemistry, biology, and medicine Physics is the mother of the natural sciences. In principle, physics can be used to explain everything that goes on at the nanoscale. There is active physics research going on in nanomechanics, quantum computation, quantum teleportation, and artificial atoms. While physics can explain everything, sometimes it is more convenient to think of nanostructures in terms of chemistry where the molecular interactions are described in terms of bonds and electron affinities. 4 Chemistry is the study of molecules and their reactions with each other. Since molecules typically have dimensions of a few nanometers, almost all of nanoscience can be reduced to chemistry. Chemistry research in nanotechnology concerns C60 molecules, carbon nanotubes, self-assembly, structures built using DNA, and supermolecular chemistry. Sometimes the chemical description of a nanostructure is insuffient to describe its function. For instance, a virus can be described best in terms of biology. Biology is sometimes described as nanotechnology that works. Biological systems contain small and efficient motors. They self reproduce. They construct tough and strong material. Biology is an important source for inspiration in nanotechnology. Copying engineering principles from biology and applying it to create new materials and technologies is called biomimetrics. Fig. 1.4. A chloroplast, where photosynthesis takes place in plants, is filled with nanoscale molecular machinery. Reference: Nanotechnology: Shaping the world atom by atom - by the U.S. National Science and Technology Council. An example of biomimetrics is trying to produce materials with the strength and lightness of seashells. Shells are strong, light materials composed of aragonite (a crystalline form of calcium carbonate which is basically chalk) and a rubbery biopolymer. Another example is a thin glass fiber grown by an ocean sponge. These glass fibers capable of transmitting light better than industrial fiber optic cables used for telecommunication. The "Venus flower basket sponge" grows the flexible fibers at cold temperatures using natural materials. If this could be reproduced in the laboratory it might avoid the problems created by current fiber optic manufacturing methods that require high temperatures and produce relatively brittle cable. Other biomimetric discoveries are enzymes taken from bacteria that break down fat in cold water have been used to improve laundry detergent and proteins from jellyfish are used during surgery to illuminate cancerous tissue. Trying to make a computer that mimics how a brain works is another example of biomimetics. 5 Fig. 1.5 (Top-left) fracture surface and (bottom-left) polished section of mollusk shell showing the micro-laminated construction responsible for its hardness, strength, and toughness. Taken from http://www.mrti.utep.edu/Full%20Pages/selfass.htm. (right) A scanning electron micrograph of the cell wall of a diatom. Diatoms are unicellular algae and major component of plankton. The circular cell membrane is about 5 μm in diameter and is made of silica (a form of glass). The algae make features in silica on the nanometer scale using just seawater and sunlight. Diatom Home Page http://www.indiana.edu/~diatom/diatom.html. Some of the applications of nanotechnology are in the field of medicine. In science fiction, miniature submarines sometimes travel through the body effecting repairs. While researcher are actively working on drug delivery systems that encapsulate drugs and release them at the point they are needed, vessels that can travel through the body would have to be far less complex than those described in the science fiction books. Nanocamera A nanodevice that often appears in science fiction is a nanocamera. This is used to view the inside of the body or in other confined spaces where an ordinary camera would not fit. Unfortunately, it is not possible to make such a camera using conventional far field optics. Light sources and light detectors can be made very small; a single molecule is large enough to serve as a simple light source or light detector. However, the amplitude of a light wave cannot change over a distance much shorter than the wavelength of the light. This means that if detectors are placed together spaced more closely than a wavelength they will all measure the same light intensity and no image will be formed. The wavelength of visible light is about one half micron so the detectors that make up a camera should be spaced at least this far apart. For an image consisting of 1000 by 1000 pixels, the camera would have to be about one half a millimeter on a side. This is small but clearly visible to the naked eye. It is too large to pass through the smallest blood vessels in the body. Using a camera of any size it is not possible to view something with the dimensions of a few nanometers using visible light. Since the amplitude of the light cannot change on a scale shorter than the wavelength, any nanoscale object viewed with visible light will be no more than a shadowy blur. One way to get around this problem is to use shorter wavelengths. X-rays have short enough wavelengths but are difficult to focus. An electron microscope can have a resolution of a few nanometers. However, there are no nanoversions of imaging systems that use these short wavelengths and x-ray photon or energetic electrons have enough energy to damage a nanoscale structure. Building a nanoscale camera that uses short wavelengths does not seem feasible. 6 Fig. 1.5. An artist's impression of a nano-louse immunizing a single red blood cell. The details shown in this drawing are too small to be seen with visible light. Recognition at the nanometer scale is done by touch. Two molecules that react with each other will bump together in random orientations until by chance they find the correct configuration and react. The molecules have to be in intimate contact for this to happen. Scanning probe microscopes also touch nanoscale objects in order to image them. This is done by bringing a sharp tip closer than 1 nm to the object that should be imaged and measuring the interactions between the nano-object and the tip. The tip is then moved around until an image is formed. Some of scanning probe imaging techniques are described in more detail in the section on topdown nanotechnology. No nanoscale versions of scanning probe microscopes are presently available or are likely to be made available in the foreseeable future. The closest thing to a nanoscale camera that we have is probably the drugs that are used in medicine. If the structure of a undesirable object such as a virus or a cancer cell is known, then a drug with a complementary structure can be made. The virus and the drug should fit together like a lock and key. When the drug comes in contact with the virus it binds to it. This either disables the virus or marks it in such a way that the body can destroy it by other means. This kind of camera can only recognize a certain shape and it is difficult to extent this concept to a general purpose camera that can see any shape. Estimate the size of an atom The object of this last section is to estimate the the size of an atom. The simplest atom, hydrogen, consists of a positively charged proton and a negatively charged electron. The force of attraction between the proton and the electron is given by Coulomb's law (Understanding Physics, Eq. 15.8), F= q1q2 r^. 4πεor2 The potential energy of the electron can be calculated by integrating the force as a function of the position (see Understanding Physics, page 87). The potential energy is, 7 U=- e² . 4πεor The potential energy is negative. The electron lowers its energy as it approaches the proton. It would seem that the electron would want to get as close to the proton as possible. However, there is another energy that prevents the electron from getting too close to the proton. This is the quantum confinement energy. The quantum confinement energy can be estimated using the Heisenberg uncertainty relation, ΔxΔpx ≥ h/(4π). For a hydrogen atom, the uncertainty in the position of the electron is about the radius of the atom Δx = r. This means that the then Δpx ≥ h/(4πr). The definition of the uncertainty in momentum is, Δpx = √ <px²> - <px>² Here the angular brackets < > signify that the average value of the quantity in the brakets should be used. Since the electron is confined to a region near the proton, the average momentum of the electron is zero, <px> = 0. This means that the average kinetic energy of the electron in the x-direction is, <px²> h² ≥ 2m 32π²mr² There is an analogous increase in the kinetic energy in the y and z directions so the total increase in kinetic energy is three times the increase calculated above. Econfinement = <px²> <py²> <pz²> 3h² + + ≥ 2m 2m 2m 32π²mr² The electron decreases its potential energy by getting close to the proton but increases its confinement energy by concentrating itself too much around the proton. The radius of an atom can be estimated by determining the radius that minimizes the total energy of the electron. The radius that minimizes U + Econfinement is, r= 3h²εo . = 4.0 × 10-11 [m]. 4πme² This is 3/4 of the Bohr radius, the true radius of an electron in hydrogen that can be calculated using a full quantum mechanical analysis. The important result of this calculation is that the kinetic energy of a particle increases as the particle is confined to a smaller region. It is the balance between this confinement energy and the electrostatic energy that is largely responsible for determining the size of atoms. This discussion also shows that quantum effects have to be considered when discussing phenomena at the nanometer scale. Reading for week 1 There's plenty of room at the bottom - by Richard Feynman. This is essential reading for anyone interested in nanotechnology. 8 References V.C. Sundar, A.D. Yablon, J. L. Grazul, M. Ilan and J. Aizenberg, "Fibre-optical features of a glass sponge," Nature vol. 424 p. 899 (2003). nanoTechnologie, Hoofdstuk 1 - VWO Masterclass gegeven door J. M. van Ruitenbeek en J. W. M. Frenken. Browse through Drexler's book, Engines of Creation. Nanotechnology: Shaping the world atom by atom - by the U.S. National Science and Technology Council. Fantastic Voyage by Isaac Asimov - Four men and a woman are reduced to a microscopic fraction of their original size, sent in a miniaturized atomic sub through a dying man's carotid artery to destroy a blood clot in his brain. If they fail, the entire world will be doomed. Problems 1. Estimate how long it would take for a single universal assembler to make a structure that weighs one gram. Estimate the maximum size of a structure that a universal assembler could create in one hour. 2. To image an object with the dimensions of a few nanometers with electromagnetic radiation, the wavelength of the radiation would have to be smaller than the obect being imaged. What kind of radiation would be necessary? What would the energy of a single photon be? Would these photons have enough energy to destroy the object being observed? 3. In Star Trek, a device call a replicator was used to create near-perfect reproductions of small objects by using a molecular pattern stored in computer memory. Most food service on starships is provided by food replicators located throughout the ship. Could this work? Could you use it to produce fuel? The science of Star Trek. 9