Writing Guide: “No beat in poetry is like no beat in a heart.”

Scholar:___________________________

Date:______

Author:____________________________

Title:__________

Mr. Schenck

Freshman English

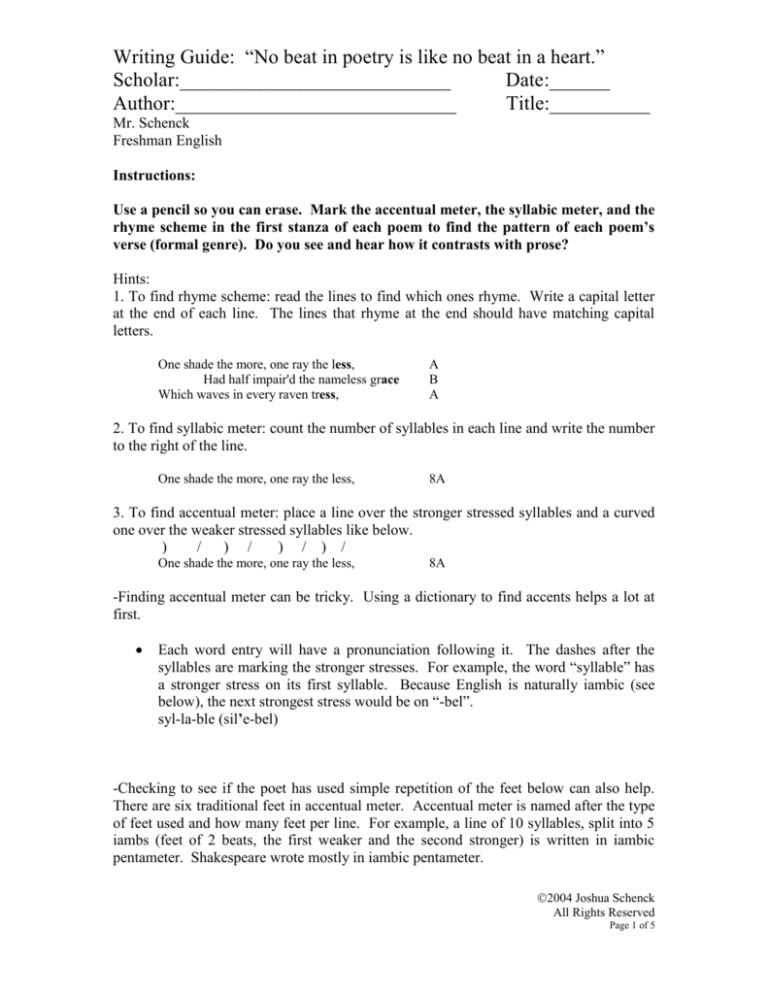

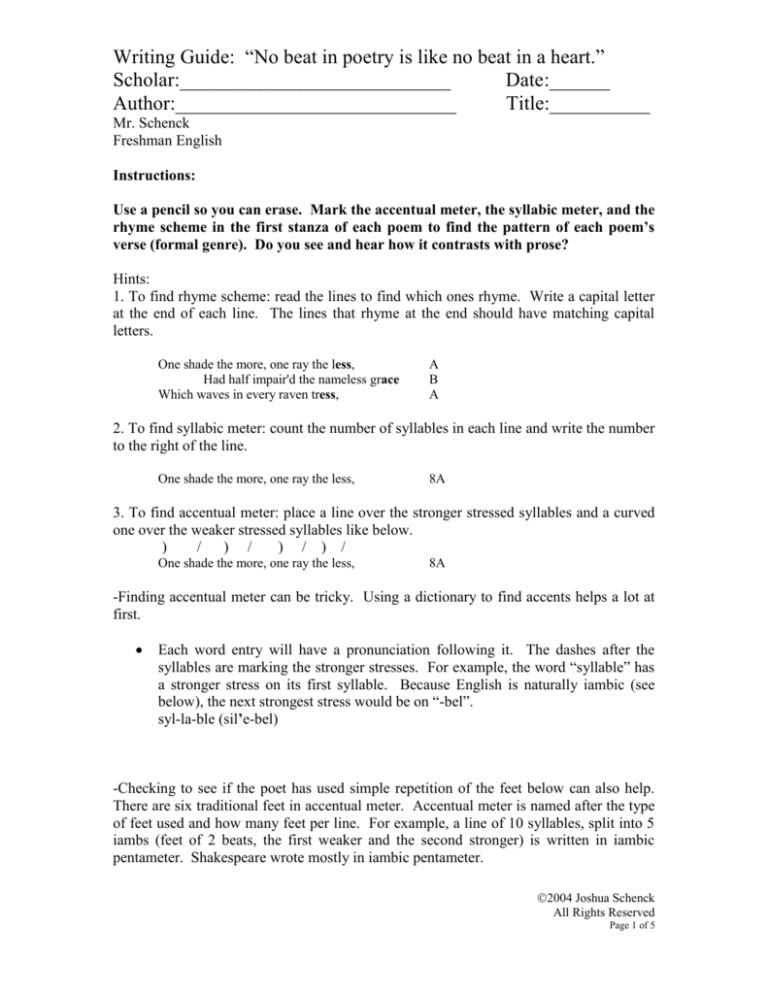

Instructions:

Use a pencil so you can erase. Mark the accentual meter, the syllabic meter, and the

rhyme scheme in the first stanza of each poem to find the pattern of each poem’s

verse (formal genre). Do you see and hear how it contrasts with prose?

Hints:

1. To find rhyme scheme: read the lines to find which ones rhyme. Write a capital letter

at the end of each line. The lines that rhyme at the end should have matching capital

letters.

One shade the more, one ray the less,

Had half impair'd the nameless grace

Which waves in every raven tress,

A

B

A

2. To find syllabic meter: count the number of syllables in each line and write the number

to the right of the line.

One shade the more, one ray the less,

8A

3. To find accentual meter: place a line over the stronger stressed syllables and a curved

one over the weaker stressed syllables like below.

)

/

) /

) / ) /

One shade the more, one ray the less,

8A

-Finding accentual meter can be tricky. Using a dictionary to find accents helps a lot at

first.

Each word entry will have a pronunciation following it. The dashes after the

syllables are marking the stronger stresses. For example, the word “syllable” has

a stronger stress on its first syllable. Because English is naturally iambic (see

below), the next strongest stress would be on “-bel”.

syl-la-ble (sil’e-bel)

-Checking to see if the poet has used simple repetition of the feet below can also help.

There are six traditional feet in accentual meter. Accentual meter is named after the type

of feet used and how many feet per line. For example, a line of 10 syllables, split into 5

iambs (feet of 2 beats, the first weaker and the second stronger) is written in iambic

pentameter. Shakespeare wrote mostly in iambic pentameter.

2004 Joshua Schenck

All Rights Reserved

Page 1 of 5

These are the different accentual metric feet.

Iambic:

)/

Trochaic:

/)

Anapestic:

))/

Dactyllic:

/))

Spondaic:

//

Pyrrhic:

))

Poets use the Greek numbers to name how many feet are in a line because the feet used in

poetry are taken from Greek writers. Add “–meter” to these number prefixes and you

have the name of how many feet are in a line. The numbers are:

1: mono2: di3: tri4: tetra5: penta6: hexa7: hepta8: octa9: nona10: deca-If you know the formal parts of speech, a few general rules help to find the meter as

well. Remember, these are general. They have exceptions.

Relative stresses can be found by knowing how strong single syllable words of

certain types are compared with other words from strongest to weakest on a scale

from 10 to 1 in which 10 is the strongest. Placing a 7 next to a 10 makes the 7

sound weaker. Placing a 7 next to a 4 makes the 7 sound stronger.

-verb:

10

run

-noun:

9

runner

-adjective:

8 (9 in a compound noun)

quick

-adverb:

8

quickly

-pronoun:

7

he

-preposition:

6 (10 in a compound verb) on

-conjunction:

4

and

-auxiliary verb:

3

to, will (to run, will run)

-nominative:

1

the, a

Roots of words or the first syllable of roots usually take stronger beats than

affixes.

English has a tendency to sound iambic, so most strong beats are followed by a

weaker one and visa-versa.

2004 Joshua Schenck

All Rights Reserved

Page 2 of 5

John Keats (1795-1821)

Ode on Melancholy

1

2

3

No, no, go not to Lethe, neither twist

Wolf's-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine;

Nor suffer thy pale forehead to be kiss'd

4

By nightshade, ruby grape of Proserpine;

5

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

6

Nor let the beetle, nor the death-moth be

7

8

9

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow's mysteries;

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

10

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies;

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Emprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

She dwells with Beauty--Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veil'd Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy's grape against his palate fine;

His soul shalt taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.

2004 Joshua Schenck

All Rights Reserved

Page 3 of 5

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

The Pains of Sleep

1

Ere on my bed my limbs I lay,

2

It hath not been my use to pray

3

With moving lips or bended knees;

4

But silently, by slow degrees,

5

My spirit I to Love compose,

6

In humble trust mine eye-lids close,

7

With reverential resignation

8

No wish conceived, no thought exprest,

9

Only a sense of supplication;

10

A sense o'er all my soul imprest

11

That I am weak, yet not unblest,

12

Since in me, round me, every where

13

Eternal strength and Wisdom are.

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

But yester-night I prayed aloud

In anguish and in agony,

Up-starting from the fiendish crowd

Of shapes and thoughts that tortured me:

A lurid light, a trampling throng,

Sense of intolerable wrong,

And whom I scorned, those only strong!

Thirst of revenge, the powerless will

Still baffled, and yet burning still!

Desire with loathing strangely mixed

On wild or hateful objects fixed.

Fantastic passions! maddening brawl!

And shame and terror over all!

Deeds to be hid which were not hid,

Which all confused I could not know

Whether I suffered, or I did:

For all seemed guilt, remorse or woe,

31

32

My own or others still the same

Life-stifling fear, soul-stifling shame.

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

So two nights passed: the night's dismay

Saddened and stunned the coming day.

Sleep, the wide blessing, seemed to me

Distemper's worst calamity.

The third night, when my own loud scream

Had waked me from the fiendish dream,

O'ercome with sufferings strange and wild,

I wept as I had been a child;

And having thus by tears subdued

My anguish to a milder mood,

Such punishments, I said, were due

To natures deepliest stained with sin,-For aye entempesting anew

The unfathomable hell within,

The horror of their deeds to view,

To know and loathe, yet wish and do!

Such griefs with such men well agree,

But wherefore, wherefore fall on me?

To be loved is all I need,

And whom I love, I love indeed.

2004 Joshua Schenck

All Rights Reserved

Page 4 of 5

George Gordon Lord Byron (1788-1824)

She Walks in Beauty

1

2

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

3

And all that's best of dark and bright

4

Meet in her aspect and her eyes:

5

6

Thus mellow'd to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

7

8

9

10

11

12

One shade the more, one ray the less,

Had half impair'd the nameless grace

Which waves in every raven tress,

Or softly lightens o'er her face;

Where thoughts serenely sweet express

How pure, how dear their dwelling-place.

13

14

15

16

17

18

And on that cheek, and o'er that brow,

So soft, so calm, yet eloquent,

The smiles that win, the tints that glow,

But tell of days in goodness spent,

A mind at peace with all below,

A heart whose love is innocent!

2004 Joshua Schenck

All Rights Reserved

Page 5 of 5