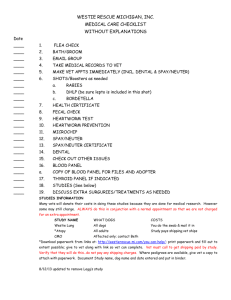

[CLICK HERE TO INSERT DOCUMENT TITLE TO FIT IN WINDOW]

advertisement

![[CLICK HERE TO INSERT DOCUMENT TITLE TO FIT IN WINDOW]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007252773_1-4b61a9d5d80ee8ed4fa9f789812dcdd2-768x994.png)