Textbook Change PT 16 - West Hills Community College District

advertisement

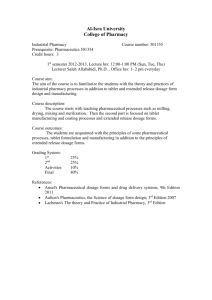

ADOPTED TEXTBOOK FORM West Hills College Coalinga Course Prefix, Number & Title: Faculty Originator: PSY TEC 16 Care of the Developmentally Disabled Frank Morales III Instructional Area: Health Careers Date: 06/11/2009 All transfer-level courses require 11-12th grade level or above. A. Title: Dosage Calculations Edition: 8th Author(s): Gloria D. Pickar Publisher: Delmar Required Publication Date Readability level: 12.4 B. Title: Edition: Author(s): Publisher: Required Readability level: C. Title: Edition: Author(s): Publisher: Required Readability level: D. Title: Edition: Author(s): Publisher: Required Readability level: ISBN #: 13-978-1-4180-8047-1 2008 (Attach readability materials to original.) ISBN #: Optional (Attach readability materials to original.) ISBN #: Optional (Attach readability materials to original.) ISBN #: Optional (Attach readability materials to original.) Name________________________________________Date_______________ Instructional Area Curriculum Representative Faculty must be in agreement on textbook change but only Curriculum Rep needs to sign. Oral Dosage of Drugs OBJECTIVES Upon mastery of Chapter 10, you will be able to calculate oral dosages of drugs. To accomplish this you will also be able to: Convert all units of measurement to the same system and same size units. Estimate the reasonable amount of the drug to be administered. Use the formula DX Q = X to calculate drug dosage. H of tablets or capsules that are contained in prescribed Calculate the number dosages. Calculate the volume of liquid per dose when the prescribed dosage is in solution form. Medications for oral administration are supplied in a variety of forms, such as tablets, capsules, and liquids. They are usually ordered to be administered by mouth, or p.o., which is an abbreviation for the Latin phrase per os. When a liquid form of a drug is unavailable, children and many elderly patients may need to have a tablet crushed or a capsule opened and mixed with a small amount of food or fluid to enable them to swallow the medication. Many of these crushed medications and oral liquids also may be ordered to be given enterally, or into the gastrointestinal tract via a specially placed tube. Such tubes and their associated enteral routes include the nasogastric (NG) tube from nares to stomach, the nasojejunal (NJ) tube from nares to jejunum, the gastrostomy tube (GT) placed directly through the abdomen into the stomach, the jejunum tube (J-tube) directly into the jejunum of the small intestines, and the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube. Page 171 ADMINISTERING MEDICATIONS TO CHILDREN Numerically, the infant's or child's dosage appears smaller, but proportionally pediatric dosages are frequently much larger per kilogram of body weight than the usual adult dosage. Infants-birth to 1 year- have a greater percentage of body water and diminished ability to absorb water-soluble drugs, necessitating dosages of oral and some parenteral drugs that are proportionally higher than those given to persons of larger size. Childrenage 1 to 12 years-metabolize drugs more readily than adults, which necessitates higher dosages. Both infants and children, however, are growing, and their organ systems" are still maturing. Immature physiological processes related to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion put them continuously at risk for overdose, toxic reactions, and even death. Adolescents-age 13 to 18 years-are often erroneously thought of as adults because of their body weight (greater than 110 pounds or 50 kilograms) and mature physical appearance. In fact, they should still be regarded as physiologically immature, with unpredictable growth spurts and hormonal surges. Drug therapy for the pediatric population is further complicated because little detailed pharmacologic research has been done on children and adolescents. The infant or child, therefore, must be frequently evaluated for desired clinical responses to medications, and serum drug levels are needed to help adjust some drug dosages. It is important to remember that administration of an incorrect dosage to adult patients is dangerous, but with a child, the risk is even greater. Therefore, using a reputable drug reference to verify safe pediatric dosages is a critical health care skill. A well-written drug reference written especially for pediatrics is Pediatric Drug Guide with Nursing Implications (Bindler & Howry, 2007). There are also a variety of pocketsize pediatric drug hand- books. Two widely used handbooks are Johns Hopkins Hospital: The Harriet Lane Handbook (2005) and Pediatric Dosage Handbook: Including Neonatal Dosing, Drug Administration, & Extemporaneous Preparations (Hodding & Kraus, 2006). I 1 Page 310 Systems of Measurement OBJECTIVES Upon mastery of Chapter 3, you will be able to recognize and express the basic systems of measurement used to calculate dosages. To accomplish this you will also be able to: Interpret and properly express metric, apothecary, and household notation. Recall metric, apothecary, and household equivalents. Explain the use of milliequivalent (mEq), international unit, unit, and milliunit in dosage calculation. To administer the correct amount of the prescribed medication to the patient, you must have a thorough knowledge of the weights and measures used in the prescription and administration of medications. The three systems used by health professionals are the metric, the apothecary, and the household systems. It is necessary for you to understand each system and how to convert from one system to another. All prescriptions should be written with the metric system, and all U.S. drug labels provide metric measurements. The household system uses measurements found in familiar containers such as teaspoons, cups, and quarts. It is helpful to understand the relationship between metric and household systems for home health care situations and discharge instructions. You may occasionally see prescriptions and medical notation using the apothecary system, usually written by physicians trained in this system. Until the metric system completely replaces the apothecary and household systems, health care professionals should be familiar with each system. Three essential parameters of measurement are associated with the prescription and administration of drugs within each system of measurement: weight, volume, and length. Weight is the most utilized parameter. It is important as a dosage unit. Most drugs are ordered and supplied by the weight of the Page 59