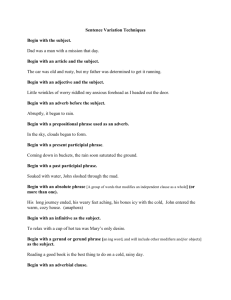

Grammar Boot Camp: Subject, Predicate, Modifiers

advertisement

Grammar Boot Camp

English 10H

Subject and Predicate

Every complete sentence contains two parts: a subject and a predicate. The subject is what (or

whom) the sentence is about, while the predicate tells something about the subject. In the following

sentences, the predicate is enclosed in braces ({}), while the subject is highlighted.

Judy {runs}.

Judy and her dog {run on the beach every morning}.

To determine the subject of a sentence, first isolate the verb and then make a question by placing

"who?" or "what?" before it -- the answer is the subject.

The audience littered the theatre floor with torn wrappings and spilled popcorn.

The verb in the above sentence is "littered." Who or what littered? The audience did. "The audience"

is the subject of the sentence. The predicate (which always includes the verb) goes on to relate

something about the subject: what about the audience? It "littered the theatre floor with torn

wrappings and spilled popcorn."

Unusual Sentences

Imperative sentences (sentences that give a command or an order) differ from conventional

sentences in that their subject, which is always "you," is understood rather than expressed.

Stand on your head. ("You" is understood before "stand.")

Be careful with sentences that begin with "there" plus a form of the verb "to be." In such sentences,

"there" is not the subject; it merely signals that the true subject will soon follow.

There were three stray kittens cowering under our porch steps this morning.

If you ask who? or what? before the verb ("were cowering"), the answer is "three stray kittens," the

correct subject.

Simple Subject and Simple Predicate

Every subject is built around one noun or pronoun (or more) that, when stripped of all the words that

modify it, is known as the simple subject. Consider the following example:

A piece of pepperoni pizza would satisfy his hunger.

The subject is built around the noun "piece," with the other words of the subject -- "a" and "of

pepperoni pizza" -- modifying the noun. "Piece" is the simple subject.

Likewise, a predicate has at its centre a simple predicate, which is always the verb or verbs that link

up with the subject. In the example we just considered, the simple predicate is "would satisfy" -- in

other words, the verb of the sentence.

A sentence may have a compound subject -- a simple subject consisting of more than one noun or

pronoun -- as in these examples:

Team pennants, rock posters and family photographs covered the boy's bedroom walls.

Her uncle and she walked slowly through the Inuit art gallery and admired the powerful sculptures

exhibited there.

The second sentence above features a compound predicate, a predicate that includes more than

one verb pertaining to the same subject (in this case, "walked" and "admired").

Modifiers

A modifier can be an adjective, an adverb, or a phrase or clause acting as an adjective or adverb In

every case, the basic principle is the same: the modifier adds information to another element in the

sentence.

In this chapter, you will begin by working with single-word modifiers -- adjectives and adverbs -- but

the information here will also apply to phrases and clauses which act as modifiers.

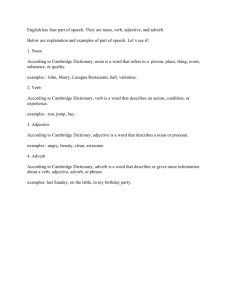

What Is An Adjective?

An adjective modifies a noun or a pronoun by describing, identifying, or quantifying words. An

adjective usually precedes the noun or the pronoun which it modifies.

In the following examples, the highlighted words are adjectives:

The truck-shaped balloon floated over the treetops.

Mrs. Morrison papered her kitchen walls with hideous wall paper.

The small boat foundered on the wine dark sea.

The coal mines are dark and dank.

Many stores have already begun to play irritating Christmas music.

A battered music box sat on the mahogany sideboard.

The back room was filled with large, yellow rain boots.

An adjective can be modified by an adverb, or by a phrase or clause functioning as an adverb. In the

sentence

My husband knits intricately patterned mittens.

for example, the adverb "intricately" modifies the adjective "patterned."

Some nouns, many pronouns, and many participle phrases can also act as adjectives. In the

sentence

Eleanor listened to the muffled sounds of the radio hidden under her pillow.

for example, both highlighted adjectives are past participles.

Grammarians also consider articles ("the," "a," "an") to be adjectives.

What is an Adverb?

An adverb can modify a verb, an adjective, another adverb, a phrase, or a clause. An adverb

indicates manner, time, place, cause, or degree and answers questions such as "how," "when,"

"where," "how much".

While some adverbs can be identified by their characteristic "ly" suffix, most of them must be

identified by untangling the grammatical relationships within the sentence or clause as a whole.

Unlike an adjective, an adverb can be found in various places within the sentence.

In the following examples, each of the highlighted words is an adverb:

The seamstress quickly made the mourning clothes.

In this sentence, the adverb "quickly" modifies the verb "made" and indicates in what manner (or how

fast) the clothing was constructed.

The midwives waited patiently through a long labour.

Similarly in this sentence, the adverb "patiently" modifies the verb "waited" and describes the manner

in which the midwives waited.

The boldly spoken words would return to haunt the rebel.

In this sentence the adverb "boldly" modifies the adjective "spoken."

We urged him to dial the number more expeditiously.

Here the adverb "more" modifies the adverb "expeditiously."

Unfortunately, the bank closed at three today.

In this example, the adverb "unfortunately" modifies the entire sentence.

Misplaced and Dangling Modifiers

You have a certain amount of freedom in deciding where to place your modifiers in a sentence:

We rowed the boat vigorously.

We vigorously rowed the boat.

Vigorously we rowed the boat.

However, you must be careful to avoid misplaced modifiers -- modifiers that are positioned so that

they appear to modify the wrong thing.

In fact, you can improve your writing quite a bit by paying attention to basic problems like misplaced

modifiers and dangling modifiers.

Misplaced Words

In general, you should place single-word modifiers near the word or words they modify, especially

when a reader might think that they modify something different in the sentence. Consider the

following sentence:

[WRONG] After our conversation lessons, we could understand the Spanish spoken by our visitors

from Madrid easily.

Do we understand the Spanish easily, or do the visitors speak it easily? This revision eliminates the

confusion:

[RIGHT] We could easily understand the Spanish spoken by our visitors from Madrid.

It is particularly important to be careful about where you put limiting modifiers. These are words like

"almost," "hardly," "nearly," "just," "only," "merely," and so on. Many writers regularly misplace these

modifiers. You can accidentally change the entire meaning of a sentence if you place these modifiers

next to the wrong word:

[WRONG] Randy has nearly annoyed every professor he has had. (he hasn't "nearly annoyed" them)

[WRONG] We almost ate all of the Thanksgiving turkey. (we didn't "almost eat" it)

[RIGHT] Randy has annoyed nearly every professor he has had.

[RIGHT] We ate almost all of the Thanksgiving turkey.

Misplaced Phrases and Clauses

It is important that you place the modifying phrase or clause as close as possible to the word or words

it modifies:

[WRONG] By accident, he poked the little girl with his finger in the eye.

[WRONG] I heard that my roommate intended to throw a surprise party for me while I was outside

her bedroom window.

[WRONG] After the wedding, Ian told us at his stag party that he would start behaving like a

responsible adult.

[RIGHT] By accident, he poked the little girl in the eye with his finger.

[RIGHT] While I was outside her bedroom window, I heard that my roommate intended to throw a

surprise party for me.

[RIGHT] Ian told us at his stag party that he would start behaving like a responsible adult after the

wedding.

Squinting Modifiers

A squinting modifier is an ambiguously placed modifier that can modify either the word before it or

the word after it. In other words, it is "squinting" in both directions at the same time:

[WRONG] Defining your terms clearly strengthens your argument. (does defining "clearly strengthen"

or does "defining clearly" strengthen?)

[RIGHT] Defining your terms will clearly strengthen your argument. OR A clear definition of your

terms strengthens your argument.

T he

Dangling

Modifier

The dangling modifier, a persistent and frequent grammatical problem in writing, is often (though not

always) located at the beginning of a sentence.

Modifiers are words, phrases, or clauses that add description. In clear, logical sentences, you will

often find modifiers right next to—either in front of or behind—the target words they logically describe.

Read this example:

Horrified, Mom snatched the deviled eggs from Jack, whose fingers were covered

in cat hair.

Notice that horrified precedes Mom, its target, just as deviled sits right before eggs. Whose fingers

were covered in cat hair follows Jack, its target.

Sometimes, however, an inexperienced writer will include a modifier but forget the target. The

modifier thus dangles because the missing target word leaves nothing for the modifier to describe.

Dangling modifiers are errors. Their poor construction confuses readers. Look at the samples below:

Hungry, the leftover pizza was devoured.

Hungry is a single-word adjective. Notice that there is no one in the sentence for this modifier to

describe.

Rummaging in her giant handbag, the sunglasses escaped detection.

Rummaging in her giant handbag is a participle phrase. In the current sentence, no word exists

for this phrase to modify. Neither sunglasses nor detection has fingers to make rummaging

possible!

W ith a sigh of disappointment, the expensive dress was returned to the rack.

With a sigh of disappointment is a string of prepositional phrases. If you look carefully, you do not

find anyone in the sentence capable of feeling disappointed. Neither dress nor rack has emotions!

Know how to fix a dangling modifier.

Fixing a dangling modifier will require more than rearranging the words in the sentence. You will often

need to add something new so that the modifier finally has a target word to describe:

Hungry, we devoured the leftover pizza.

Rummaging in her giant handbag, Frieda failed to find her sunglasses.

W ith a sigh of disappointment, Charlene returned the expensive dress to the rack.

Phrase

A phrase is a group of two or more grammatically linked words without a subject and predicate –

Clause

A clause is a collection of grammatically-related words including a predicate and a

subject (though sometimes the subject is implied).

The

Linking

Verb

Recognize a linking verb when you see one.

Linking verbs do not express action. Instead, they connect the subject of the verb to additional

information about the subject. Look at the examples below:

Keila is a shopaholic.

Ising isn't something that Keila can do. Is connects the subject, Keila, to additional information about

her, that she will soon have a huge credit card bill to pay.

During the afternoon, my cats are content to nap o n the couch.

Areing isn't something that cats can do. Are is connecting the subject, cats, to something said about

them, that they enjoy sleeping on the furniture.

After drinking the old milk, Vladimir turned green.

Turned connects the subject, Vladimir, to something said about him, that he needed an antacid.

A ten-item quiz seems impossibly long after a night of no studying.

Seems connects the subject, a ten-item quiz, with something said about it, that its difficulty depends

on preparation, not length.

Irene always feels sleepy after pigging out on pizza from Antonio's.

Feels connects the subject, Irene, to her state of being, sleepiness.

The following verbs are true linking verbs: any form of the verb be [am, is, are, was, were, has been,

are being, might have been, etc.], become, and seem. These true linking verbs are always linking

verbs.

Then you have a list of verbs with multiple personalities: appear, feel, grow, look, prove, remain,

smell, sound, taste, and turn. Sometimes these verbs are linking verbs; sometimes they are action

verbs.

How do you tell when they are action verbs and when they are linking verbs?

If you can substitute am, is, or are and the sentence still sounds logical, you have a linking verb on

your hands.

If, after the substitution, the sentence makes no sense, you are dealing with an action verb instead.

Here are some examples:

Sylvia tasted the spicy squid eyeball stew.

Sylvia is the stew? I don't think so! Tasted, therefore, is an action verb in this sentence, something

Sylvia is doing.

The squid eyeball stew tasted good.

The stew is good? You bet. Make your own!

I smell the delicious aroma of a mushroom and papaya pizza baking in the oven.

I am the aroma? No way! Smell, in this sentence, is an action verb, something I am doing.

The mushroom and papaya pizza smells heavenly.

The pizza is heavenly? Definitely! Try a slice!

W hen my dog Oreo felt the wet grass beneath her paws, she bolted up the stairs and

curled up on the couch.

Oreo is the wet grass? Of course not! Here, then, felt is an action verb, something Oreo is doing.

My dog Oreo feels depressed after seven straight days of rain.

Oreo is depressed? Without a doubt! Oreo hates the wet.

This substitution will not work for appear. With appear, you have to analyze the function of the verb.

Swooping out of the clear blue sky, the blue jay appeared on the branch.

Appear is something a blue jay can do—especially when food is near.

The blue jay appeared happy to see the bird feeder.

Here, appeared is connecting the subject, the blue jay, to its state of mind, happiness.

The

Subject

Complement

A subject complement is the adjective, noun, or pronoun that follows a linking verb.

The following verbs are true linking verbs: any form of the verb be [am, is, are, was, were, has been,

are being, might have been, etc.], become, and seem. These true linking verbs are always linking

verbs.

Then you have a list of verbs that can be linking or action: appear, feel, grow, look, prove, remain,

smell, sound, taste, and turn. If you can substitute any of the verbs on this second list with an equal

sign [=] and the sentence still makes sense, the verb is almost always linking.

Read these examples:

Brandon is a gifted athlete.

Brandon = subject; is = linking verb; athlete = noun as subject complement.

It was he who caught the winning touchdown Friday night.

It = subject; was = linking verb; he = pronoun as subject complement.

Brandon becomes embarrassed when people compliment his skill.

Brandon = subject; becomes = linking verb; embarrassed = adjective as subject complement.

Brandon's face will turn red.

Face = subject; will turn = linking verb; red = adjective as subject complement. [Will turn is linking

because if you substitute this verb with an equal sign, the sentence still makes sense.]

Don't mistake a subject complement for a direct object.

Only linking verbs can have subject complements. If the verb is action, then the word that answers

the question what? or who? after the subject + verb is a direct object.

W hen Michelle woke up this morning, she felt sick.

She = subject; felt = linking verb; sick = subject complement. [Felt is linking because if you substitute

this verb with an equal sign, the sentence still makes sense.]

Michelle felt her forehead but did not detect a temperature.

Michelle = subject; felt = action verb. She felt what? Forehead = direct object. [Felt is action

because if you substitute this felt with an equal sign, the sentence does not make sense.]

Use subject pronouns as subject complements.

The chart below contains subject and object pronouns. Because a subject complement provides more

information about the subject, use the subject form of the pronoun—even when it sounds strange.

Subject Pronouns

I

we

you

he, she, it

they

who

Object Pronouns

me

us

you

him, her, it

them

whom

Check out these sample sentences:

Don't blame Gerard. It was I who woke you from a sound sleep.

It = subject; was = linking verb; I = subject complement.

Don't get mad at me! I didn't pull your ponytail! It was he.

It = subject; was = linking verb; he = subject complement.

Remember the amazing guitarist I met? This is she.

This = subject; is = linking verb; she = subject complement.

Day Two:

imperative, indirect objects, verb phrases

im·per·a·tive ( m-p r -t v)

adj.

1. Expressing a command or plea; peremptory: requests that grew more and more imperative.

2. Having the power or authority to command or control.

3. Grammar Of, relating to, or constituting the mood that expresses a command or request.

4. Impossible to deter or evade; pressing: imperative needs. See Synonyms at urgent.

n.

1.

a. A command; an order.

b. An obligation; a duty: social imperatives.

2. A rule, principle, or instinct that compels a certain behavior: a people driven to aggression by territo

3. Grammar

a. The imperative mood.

b. A verb form of the imperative mood.

Indirect object An indirect object (which, like a direct object, is always a noun or pronoun) is,

in a sense, the recipient of the direct object. To determine if a verb has an indirect object, isolate the

verb and ask to whom?, to what?, for whom?, or for what? after it. The answer is the indirect object.

The

Indirect

Object

Indirect objects are rare. You can read for pages before you encounter one. For an indirect object to

appear, a sentence must first have a direct object.

Direct objects follow transitive verbs [a type of action verb]. If you can identify the subject and verb

in a sentence, then finding the direct object—if one exists—is easy. Just remember this simple

formula:

s u b j e c t + v e r b + what? or who? = d i r e c t o b j e c t

Here are examples of the formula in action:

Jim built a sandcastle on the beach.

Jim = subject; built = verb. Jim built what? Sandcastle = direct object.

Sammy and Maria brought Billie Lou to the party.

Sammy, Maria = subject; brought = verb. Sammy and Maria brought who? Billie Lou = direct

object.

To explain the broken lamp, we told a lie.

We = subject; told = verb. We told what? Lie = direct object.

When someone [or something] gets the direct object, that word is the indirect object. Look at these

new versions of the sentences above:

Jim built his granddaughter a sandcastle on the beach.

Jim = subject; built = verb. Jim built what? Sandcastle = direct object. Who got the sandcastle?

Granddaughter = indirect object.

So that Darren would have company at the party, Sammy and Maria brought him a

blind date.

Sammy, Maria = subjects; brought = verb. Sammy and Maria brought who? Blind date = direct

object. Who got the blind date? Him = indirect object.

To explain the broken lamp, we told Mom a lie.

We = subject; told = verb. We told what? Lie = direct object. Who got the lie? Mom = indirect object.

Sometimes, the indirect object will occur in a prepositional phrase beginning with to or for. Read

these two sentences:

Tomas paid the mechanic 200 dollars to fix the squeaky brakes.

Tomas paid 200 dollars to the mechanic to fix the squeaky brakes.

In both versions, the mechanic [the indirect object] gets the 200 dollars [the direct object].

When the direct object is a pronoun rather than a noun, putting the indirect object in a prepositional

phrase becomes a necessary modification. The preposition smoothes out the sentence so that it

sounds natural. Check out these examples:

Leslie didn't have any money for a sandwich, so Smitty purchased her it.

Blech! That version sounds awful! But now try the sentence with the indirect object after a preposition:

Leslie didn't have any money for a sandwich, so Smitty purchased it for her.

Locating the indirect object her in a prepositional phrase lets the sentence sound natural! Now read

this example:

After Michael took generous spoonfuls of stuffing, he passed us it.

Ewww! This version sounds awful too! But with a quick fix, we can solve the problem:

After Michael took generous spoonfuls of stuffing, he passed it to us.

With the indirect object us in a prepositional phrase, we have an improvement!

The

Verb

Phrase

Every sentence must have a verb. To depict doable activities, writers use action verbs. To describe

conditions, writers choose linking verbs.

Sometimes an action or condition occurs just once—pow!—and it's over. Read these two short

sentences:

Offering her license and registration, Selena sobbed in the driver's seat.

Officer Carson was unmoved.

Other times, the activity or condition continues over a long stretch of time, happens predictably, or

occurs in relationship to other events. In these instances, a single-word verb like sobbed or was

cannot accurately describe what happened, so writers use multipart verb phrases to communicate

what they mean. As many as four words can comprise a verb phrase.

A main or base verb indicates the type of action or condition, and auxiliary—or helping—verbs convey

the other nuances that writers want to express.

Read these three examples:

The tires screeched as Selena mashed the accelerator.

Selena is always disobeying the speed limit.

Selena should have been driving with more care, for then she would not have gotten

her third ticket this year.

In the first sentence, screeched and mashed, single-word verbs, describe the quick actions of both

the tires and Selena.

Since Selena has an inclination to speed, is disobeying [a two-word verb] communicates the

frequency of her law breaking. The auxiliary verbs that comprise should have been driving [a fourword verb] and would have gotten [a three-word verb] express not only time relationships but also

evaluation of Selena's actions.

Realize that an adverb is not part of the verb phrase.

Since a verb phrase might use up to four words, a short adverb—such as also, never, or not—might

try to sneak in between the parts. When you find an adverb snuggled in a verb phrase, it is still an

adverb, not part of the verb. Read these examples:

For her birthday, Selena would also like a radar detector.

Would like = verb; also = adverb.

To avoid another speeding ticket, Selena will never again take her eyes off the road

to fiddle with the radio.

Will take = verb; never, again = adverbs.

Despite the stern warning from Officer Carson, Selena has not lightened her foot on

the accelerator.

Has lightened = verb; not = adverb.

Day Three: Prepositional Phrases

A preposition links nouns, pronouns and phrases to other words in a sentence. The word or phrase

that the preposition introduces is called the object of the preposition.

A preposition usually indicates the temporal, spatial or logical relationship of its object to the rest of

the sentence as in the following examples:

The book is on the table.

The book is beneath the table.

The book is leaning against the table.

The book is beside the table.

She held the book over the table.

She read the book during class.

In each of the preceding sentences, a preposition locates the noun "book" in space or in time.

A prepositional phrase is made up of the preposition, its object and any associated adjectives or

adverbs. A prepositional phrase can function as a noun, an adjective, or an adverb. The most

common prepositions are "about," "above," "across," "after," "against," "along," "among," "around,"

"at," "before," "behind," "below," "beneath," "beside," "between," "beyond," "but," "by," "despite,"

"down," "during," "except," "for," "from," "in," "inside," "into," "like," "near," "of," "off," "on," "onto," "out,"

"outside," "over," "past," "since," "through," "throughout," "till," "to," "toward," "under," "underneath,"

"until," "up," "upon," "with," "within," and "without."

Each of the highlighted words in the following sentences is a preposition:

The children climbed the mountain without fear.

In this sentence, the preposition "without" introduces the noun "fear." The prepositional phrase

"without fear" functions as an adverb describing how the children climbed.

There was rejoicing throughout the land when the government was defeated.

Here, the preposition "throughout" introduces the noun phrase "the land." The prepositional phrase

acts as an adverb describing the location of the rejoicing.

The spider crawled slowly along the banister.

The preposition "along" introduces the noun phrase "the banister" and the prepositional phrase "along

the banister" acts as an adverb, describing where the spider crawled.

The dog is hiding under the porch because it knows it will be punished for chewing up a new pair of

shoes.

Here the preposition "under" introduces the prepositional phrase "under the porch," which acts as an

adverb modifying the compound verb "is hiding."

The screenwriter searched for the manuscript he was certain was somewhere in his office.

Similarly in this sentence, the preposition "in" introduces a prepositional phrase "in his office," which

acts as an adverb describing the location of the missing papers.

The

Prepositional

Phrase

At the minimum, a prepositional phrase will begin with a preposition and end with a noun, pronoun,

gerund, or clause, the "object" of the preposition.

The object of the preposition will often have one or more modifiers to describe it. These are the

patterns for a prepositional phrase:

preposition +noun, pronoun, gerund, or clause

preposition +modifier(s) +noun, pronoun, gerund, or clause

Here are some examples of the most basic prepositional phrase:

At home

At = preposition; home = noun.

In time

In = preposition; time = noun.

From Richie

From = preposition; Richie = noun.

W ith me

With = preposition; me = pronoun.

By singing

By = preposition; singing = gerund.

About what we need

About = preposition; what we need = noun clause.

Most prepositional phrases are longer, like these:

From my grandmother

From = preposition; my = modifier; grandmother = noun.

Under the warm blanket

Under = preposition; the, warm = modifiers; blanket = noun.

In the weedy, overgrown garden

In = preposition; the, weedy, overgrown = modifiers; garden = noun.

Along the busy, six-lane highway

Along = preposition; the, busy, six-lane = modifiers; highway = noun.

W ithout excessively worrying

Without = preposition; excessively = modifier; worrying = gerund.

Understand what prepositional phrases do in a sentence.

A prepositional phrase will function as an adjective or adverb. As an adjective, the prepositional

phrase will answer the question Which one?

Read these examples:

The book on the bathroom floor is swollen from shower steam.

Which book? The one on the bathroom floor!

The sweet potatoes in the vegetable bin are green with mold.

Which sweet potatoes? The ones forgotten in the vegetable bin!

The note from Beverly confessed that she had eaten the leftover pizza.

Which note? The one from Beverly!

As an adverb, a prepositional phrase will answer questions such as How? When? or Where?

Freddy is stiff from yesterday's long football practice .

How did Freddy get stiff? From yesterday's long football practice!

Before class, Josh begged his friends for a pencil.

When did Josh do his begging? Before class!

Feeling brave, we tried the Dragon Breath Burritos at Tito's Taco Palace .

Where did we eat the spicy food? At Tito's Taco Palace!

Remember that a prepositional phrase will never contain the subject of a sentence.

Sometimes a noun within the prepositional phrase seems the logical subject of a verb. Don't fall for

that trick! You will never find a subject in a prepositional phrase. Look at this example:

Neither of these cookbooks contains the recipe for Manhattan -style squid eyeball

stew.

Cookbooks do indeed contain recipes. In this sentence, however, cookbooks is part of the

prepositional phrase of these cookbooks. Neither—whatever a neither is—is the subject for the verb

contains.

Neither is singular, so you need the singular form of the verb, contains. If you incorrectly identified

cookbooks as the subject, you might write contain, the plural form, and thus commit a subject-verb

agreement error.

Some prepositions—such as along with and in addition to—indicate "more to come." They will make

you think that you have a plural subject when in fact you don't. Don't fall for that trick either! Read this

example:

Tommy, along with the other students , breathed a sigh of relief when Mrs. Markham

announced that she was postponing the due date for the research essay.

Logically, more than one student is happy with the news. But Tommy is the only subject of the verb

breathed. His classmates count in the real world, but in the sentence, they don't matter, locked as

they are in the prepositional phrase.

Day Four: Compounds and interjections

The

Compound

Subject

Every verb in a sentence must have at least one subject. But that doesn't mean that a verb can have

only one subject. Some verbs are greedy as far as subjects go. A greedy verb can have two, three,

four, or more subjects all to itself. When a verb has two or more subjects, you can say that the verb

has a compound subject. Check out the following examples:

At the local Dairy Queen, Marsha gasped at the sight of pickle slices on her banana

split.

Marsha = subject; gasped = verb.

At the local Dairy Queen, Jenny and Marsha gasped at the sight of pickle slices on

their banana splits.

Jenny, Marsha = compound subject; gasped = verb.

At the local Dairy Queen, Officer Jenkins, Mrs. Lowery, the W illiams twins, Harold,

Billy Jo , Jenny, and Marsha gasped at the sight of pickle slices on their banana

splits.

Officer Jenkins, Mrs. Lowery, the Williams twins, Harold, Billy Jo, Jenny, Marsha = compound subject;

gasped = verb.

The

Compound

Verb

Every subject in a sentence must have at least one verb. But that doesn't mean that a subject can

have only one verb. Some subjects are greedy as far as verbs go. A greedy subject can have two,

three, four, or more verbs all to itself. When a subject has two or more verbs, you can say that the

subject has a compound verb. Check out the following examples:

Before mixing the ingredients for his world -famous cookies, Bobby swatted a fly

buzzing around the kitchen.

Bobby = subject; swatted = verb.

Before mixing the ingredients for his world -famous cookies, Bobby swatted a fly

buzzing around the kitchen and crushed a cockroach scurrying across the floor.

Bobby = subject; swatted, crushed = compound verb.

Before mixing the ingredients for his world -famous cookies, Bobby swatted a fly

buzzing around the kitchen, crushed a cockroach scurrying across the floor, shooed

the cat off the counter, picked his nose, scratched his armpit, licked his fingers, and

sneezed.

Bobby = subject; swatted, crushed, shooed, picked, scratched, licked, sneezed = compound

verb.

T he

Inter jection

To capture short bursts of emotion, you can use an interjection, which is a single word, phrase, or

short clause that communicates the facial expression and body language that the sentence itself will

sometimes neglect.

Interjections are thus like emoticons. One writer might write the sentence like this:

The burrito is vegan. :-)

Or like this:

The burrito is vegan. ☺

But another writer might use an interjection to express that same burst of happiness:

The burrito is vegan. Yum!

The interjection yum lets us see the emotional response to the information in the sentence. If the

writer was really hoping for spicy ground beef in the burrito, notice how a different interjection

communicates the disappointment:

The burrito is vegan. :-(

The burrito is vegan. ☹

The burrito is vegan. Yuck!

Interjections are common in spoken English, so they are appropriate if you are capturing dialogue in

your writing. Read this example:

My colleague in the physics lab shouted, " Hooray! They made the right decision!"

when she learned that the International Astronomical Union (IAU) demoted Pluto to

dwarf planet.

Interjections are also appropriate in informal communication, like texts or emails to friends:

Groovy! IAU demotes Pluto!!!

But when you read, you'll notice that writers seldom use interjections in professional publications like

textbooks, newspapers, or magazines. Never, for example, would an important science journal

include a sentence like this one:

Oh, snap! The IAU has added gravitational dominanc e as a requirement for

planethood.

Good writers know that careful word choice can capture the same emotion and body language that

the interjection communicates. In the sentence below, we recognize the writer’s unhappiness even

though we find no interjection:

Worse than the refried beans was the disappointment that spread over my tongue as I

bit into the vegan burrito.

Know the different kinds of interjections.

Some words are primarily interjections. Below is a list.

bazinga

blech

boo-yah

duh

eek

eureka

eww

gak

geez

ha

hello

hooray

huh

oh

oops

ouch

oy

ugh

uh-oh

whammo

whew

whoa

wow

yahoo

yikes

yippee

yo

yowza

yuck

yum

However, any word, phrase, or short clause that captures an emotional burst can function as an

interjection. So if you write, Emily has switched her major to chemistry, you could use an

adjective, for example, as an interjection:

Sweet! Emily has switched her major to chemistry.

A noun or noun phrase would also work:

Congratulations, Emily has switched her major to chemistry.

Emily has switched her major to chemistry . Way to go!

Holy macaroni! Emily has switched her major to chemistry.

Or you could use a short clause:

Emily has switched her major to chemistry. She rocks!

Notice that the sentence itself, Emily has switched her major to chemistry, doesn't provide an

emotional reaction to the information. The interjection does that job. And remember, not everyone

might be congratulatory and happy:

Emily has switched her major to chemistry. Oh, the horror!

Know how to punctuate interjections.

Punctuation for an interjection will depend on the emotion and body language you hope to capture.

Strong emotions, such as anger, excitement, or surprise, need an exclamation point [!] to

communicate the intensity.

Ugh! I cannot believe we are eating leftover vegan burritos for a third night.

Yowza! That's an astrophysicist dancing in the hallway!

An interjection meant to illustrate confusion, uncertainty, or disbelief will require a question mark [?] to

help capture the open mouth, shrug, blank look, or rolled eyes.

Huh? You want me—the person with a D average —to help with your calculus

homework?

Oh, really? You killed a rattlesnake with a salad fork?

A comma [,] or period [.] will indicate weaker emotions, like indifference, doubt, or disdain. These two

marks of punctuation dial down the volume on the sentence.

Meh, I don't really care that Pluto is no longer a planet.

Pssst. Do you have the answer for number 7?

Here comes Prof. Phillips. Uh-oh, did he catch sight of you r cheat sheet?

It looks like George is skipping class even though our group presentation is due

today. Typical.

Day Five: Appositive and gerunds

T he

A ppositive

An appositive is a noun or noun phrase that renames another noun right beside it. The appositive can

be a short or long combination of words. Look at these examples:

The insect, a cockroach, is crawling across the kitchen table.

The insect, a large cockroach , is crawling across the kitchen table.

The insect, a large cockroach with hairy legs , is crawling across the kitchen table.

The insect, a large, hairy -legged cockroach that has spied my bowl of oatmeal , is

crawling across the kitchen table.

Here are more examples:

During the dinner conversation, Clifford, the messiest eater at the table , spewed

mashed potatoes like an erupting volcano.

My 286 computer, a modern-day dinosaur, chews floppy disks as noisily as my

brother does peanut brittle.

Genette's bedroom desk, the biggest disaster area in the house , is a collection of

overdue library books, dirty plates, computer components, old mail, cat hair, and

empty potato chip bags.

Reliable, Diane's eleven -year-old beagle, chews holes in the living room carpeting as

if he were still a puppy.

Punctuate the appositive correctly.

The important point to remember is that a nonessential appositive is always separated from the rest

of the sentence with comma(s).

When the appositive begins the sentence, it looks like this:

A hot-tempered tennis player, Robbie charged the umpire and tried to crack the poor

man's skull with a racket.

When the appositive interrupts the sentence, it looks like this:

Robbie, a hot-tempered tennis player, charged the umpire and tried to crack the poor

man's skull with a racket.

And when the appositive ends the sentence, it looks like this:

Upset by the bad call, the crowd cheered Robbie , a hot-tempered tennis player who

charged the umpire and tried to crack the poor man's skull with a racket.

T he

Ger und

Every gerund, without exception, ends in ing. Gerunds are not, however, all that easy to identify. The

problem is that all present participles also end in ing. What is the difference?

Gerunds function as nouns. Thus, gerunds will be subjects, subject complements, direct objects,

indirect objects, and objects of prepositions.

Present participles, on the other hand, complete progressive verbs or act as modifiers.

Read these examples of gerunds:

Since Francisco was five years old, swimming has been his passion.

Swimming = subject of the verb has been.

Francisco's first love is swimming.

Swimming = subject complement of the verb is.

Francisco enjoys swimming more than spending time with his girlfriend Diana.

Swimming = direct object of the verb enjoys.

Francisco gives swimming all of his energy and time.

Swimming = indirect object of the verb gives.

W hen Francisco wore dive fins to class, everyone knew that he was devoted to

swimming.

Swimming = object of the preposition to.

These ing words are examples of present participles:

One day last summer, Francisco and his coach were swimming at Daytona Beach.

Swimming = present participle completing the past progressive verb were swimming.

A Great W hite shark ate Francisco's swimming coach.

Swimming = present participle modifying coach.

Now Francisco practices his sport in safe swimming pools.

Swimming = present participle modifying pools.

Day Six: Participles

T he

Par ticiple

Recognize a participle when you see one.

Participles come in two varieties: past and present. They are two of the five forms or principal parts

that every verb has. Look at the charts below.

R e g u l a r Ve r b s :

giggled

helped

Past

Participle

giggled

helped

Present

Participle

giggling

helping

jumped

jumped

jumping

Present

Participle

bringing

ringing

singing

swimming

Verb

Simple Present

Simple Past

giggle

help

giggle(s)

help(s)

jump

jump(s)

Infinitive

to giggle

to help

to jump

I r r e g u l a r Ve r b s :

Verb

Simple Present

Simple Past

bring

ring

sing

bring(s)

ring(s)

sing(s)

brought

rang

sang

Past

Participle

brought

rung

sung

swim

swim(s)

swam

swum

Infinitive

to bring

to ring

to sing

to swim

Notice that each present participle ends in ing. This is the case 100 percent of the time.

On the other hand, you can see that past participles do not have a consistent ending. The past

participles of all regular verbs end in ed; the past participles of irregular verbs, however, vary

considerably. If you look at bring and sing, for example, you'll see that their past participles—

brought and sung—do not follow the same pattern even though both verbs have ing as the last

three letters.

Consult a dictionary whenever you are unsure of a verb's past participle form.

Know the functions of participles.

Participles have three functions in sentences. They can be components of multipart verbs, or they

can function as adjectives or nouns.

P a r t i c i p l e s i n M u l t i p a r t Ve r b s

A verb can have as many as four parts. When you form multipart verbs, you use a combination of

auxiliary verbs and participles. Look at the examples below:

Our pet alligator ate Mrs. Olsen's poodle.

Ate = simple past tense [no participle].

W ith a broom, Mrs. Olsen was beating our alligator over the head in an attempt to

retrieve her poodle.

Was = auxiliary verb; beating = present participle.

Our pet alligator has been stalking neighborhood pets because my brother Billy

forgets to feed the poor reptile.

Has = auxiliary verb; been = past participle; stalking = present participle.

Our pet alligator should have been eating Gator Chow, crunchy nuggets that Billy

leaves for him in a bowl.

Should, have = auxiliary verbs; been = past participle; eating = present participle.

P a r t i c i p l e s a s Ad j e c t i v e s

Past and present participles often function as adjectives that describe nouns. Here are some

examples:

The crying baby dre w a long breath and sucked in a spider crouching in the corner of

the crib.

Which baby? The crying baby. Which spider? The one that was crouching in the corner.

The mangled pair of sunglasses, bruised face, broken arm, and bleeding knees meant

Genette had taken another spill on her mountain bike.

Which pair of sunglasses? The mangled pair. Which face? The bruised one. Which arm? The broken

one. Which knees? The bleeding ones.

Participles as Nouns

Present participles can function as nouns—the subjects, direct objects, indirect objects, objects of

prepositions, and subject complements in sentences. Whenever a present participle functions as a

noun, you call it a gerund.

Take a look at these examples:

Sneezing exhausts Steve, who requires eight tissues and twenty -seven Gesundheits

before he is done.

Sneezing = the subject of the verb exhausts.

Valerie hates cooking because scraping burnt gook out of pans always undermines

her enjoyment of the food.

Cooking = the direct object of the verb hates.

We gave bungee jumping a chance.

Bungee jumping = indirect object of the verb gave.

Joelle bit her tongue instead of criticizing her prom date's powder blue tuxedo.

Criticizing = object of the preposition instead of.

Omar's least favorite sport is water-skiing because a bad spill once caused him to

lose his swim trunks.

Water-skiing = the subject complement of the verb is.

T he

Par ticiple

Phr ase

A participle phrase will begin with a present or past participle. If the participle is present, it will

dependably end in ing. Likewise, a regular past participle will end in a consistent ed. Irregular past

participles, unfortunately, conclude in all kinds of ways [although this list will help].

Since all phrases require two or more words, a participle phrase will often include objects and/or

modifiers that complete the thought. Here are some examples:

Crunching caramel corn for the entire movie

Washed with soap and water

Stuck in the back of the closet behind the obsolete computer

Participle phrases always function as adjectives, adding description to the sentence. Read these

examples:

The horse trotting up to the fence hopes that you have an apple or carrot.

Trotting up to the fence modifies the noun horse.

The water drained slowly in the pipe clogged with dog hair.

Clogged with dog hair modifies the noun pipe.

Eaten by mosquitoes, we wished that we had made hotel, not campsite, reservations.

Eaten by mosquitoes modifies the pronoun we.

Don't mistake a present participle phrase for a gerund phrase.

Gerund and present participle phrases are easy to confuse because they both begin with an ing word.

The difference is the function that they provide in the sentence. A gerund phrase will always behave

as a noun while a present participle phrase will act as an adjective. Check out these examples:

Walking on the beach , Delores dodged jellyfish that had washed ashore.

Walking on the beach = present participle phrase describing the noun Delores.

Walking on the beach is painful if jellyfish have washed ashore.

Walking on the beach = gerund phrase, the subject of the verb is.

Waking to the buzz of the alarm clock , Freddie cursed the arrival of another Mon day.

Waking to the buzz of the alarm clock = present participle phrase describing the noun Freddie.

Freddie hates waking to the buzz of the alarm clock .

Waking to the buzz of the alarm clock = gerund phrase, the direct object of the verb hates.

After a long day at school and work, LaShae found her roommate Ben eating the last

of the leftover pizza .

Eating the last of the leftover pizza = present participle phrase describing the noun Ben.

Ben's rudest habit is eating the last of the leftover pizza .

Eating the last of the leftover pizza = gerund phrase, the subject complement of the linking verb is.

Punctuate a participle phrase correctly.

When a participle phrase introduces a main clause, separate the two sentence components with a

comma. The pattern looks like this:

participle phrase +,+main clause.

Read this example:

Glazed with barbecue sauce, the rack of ribs lay nestled next to a pile of sweet

coleslaw.

When a participle phrase concludes a main clause and is describing the word right in front of it, you

need no punctuation to connect the two sentence parts. The pattern looks like this:

main clause +Ø+participle phrase.

Check out this example:

Mariah risked petting the pit bull wagging its stub tail.

But when a participle phrase concludes a main clause and modifies a word farther up in the sentence,

you will need a comma. The pattern looks like this:

main clause +,+participle phrase.

Check out this example:

Cooper enjoyed dinner at Audrey's house, agreeing to a large slice of cherry pie even

though he was fu ll to the point of bursting .

Don't misplace or dangle your participle phrases.

Participle phrases are the most common modifier to misplace or dangle. In clear, logical sentences,

you will find modifiers right next to the words they describe.

Shouting with happiness, W illiam celebrated his chance to interview at SunTrust.

Notice that the participle phrase sits right in front of William, the one doing the shouting.

If too much distance separates a modifier and its target, the modifier is misplaced.

Draped neatly on a hanger, W illiam borrowed Grandpa's old suit to wear to the

interview.

The suit, not William, is on the hanger! The modifier must come closer to the word it is meant to

describe:

For the interview, W illiam borrowed Grandpa's old suit, which was draped neatly on a

hanger.

If the sentence fails to include a target, the modifier is dangling.

Straightening his tie and smoothing his hair, the appointment time for the interview

had finally arrived.

We assume William is about to interview, but where is he in the sentence? We need a target for the

participle phrase straightening his tie and smoothing his hair.

Straightening his tie and smoothing his hair, W illiam was relieved that the

appointment time for the interview had finally arrived.

Day Seven: Infinitives

T he

Infinitive

To sneeze, to smash, to cry, to shriek, to jump, to dunk, to read, to eat, to slurp—all of these are

infinitives. An infinitive will almost always begin with to followed by the simple form of the verb, like

this:

t o + v e r b = infinitive

Important Note: Because an infinitive is not a verb, you cannot add s, es, ed, or ing to the end.

Ever!

Infinitives can be used as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs. Look at these examples:

To sleep is the only thing Eli wants after his double shift waiting tables at the

neighborhood café.

To sleep functions as a noun because it is the subject of the sentence.

No matter how fascinating the biology dissection is, Emanuel turns his head and

refuses to look.

To look functions as a noun because it is the direct object for the verb refuses.

W herever Melissa goes, she always brings a book to read in case conversation lags

or she has a long wait.

To read functions as an adjective because it modifies book.

Richard braved the icy rain to throw the smelly squid eyeball stew into the apartment

dumpster.

To throw functions as an adverb because it explains why Richard braved the inclement weather.

Recognize an infinitive even when it is missing the to.

An infinitive will almost always begin with to. Exceptions do occur, however. An infinitive will lose its to

when it follows certain verbs. These verbs are feel, hear, help, let, make, see, and watch.

The pattern looks like this:

special verb +direct object +infinitive -to

Here are some examples:

As soon as Theodore felt the rain splatter on his hot, dusty skin, he knew that he had

a good excuse to return the lawn mower to the garage.

Felt = special verb; rain = direct object; splatter = infinitive minus the to.

W hen Danny heard the alarm clock buzz , he slapped the snooze button and burrow ed

under the covers for ten more minutes of sleep.

Heard = special verb; alarm clock = direct object; buzz = infinitive minus the to.

Although Dr. Ribley spent an extra class period helping us understand logarithms, we

still bombed the test.

Helping = special verb; us = direct object; understand = infinitive minus the to.

Because Freddie had never touched a snake, I removed the cover of the cage and let

him pet Squeeze, my seven -foot python.

Let = special verb; him = direct object; pet = infinitive minus the to.

Since Jose had destroyed Sylvia's spotless kitchen while baking chocolate -broccoli

muffins, she made him take her out for an expensive dinner.

Made = special verb; him = direct object; take = infinitive minus the to.

I said a prayer when I saw my friends mount the Kumba, a frightening roller coaster

that twists and rolls like a giant sea serpent.

Saw = special verb; my friends = direct object; mount = infinitive minus the to.

Hoping to lose her fear of flying, Rachel went to the airport to watch passenger

planes take off and land , but even this exercise did not convince her that jets were

safe.

Watch = special verb; passenger planes = direct object; take, land = infinitives minus the to.

To split or not to split?

The general rule is that no word should separate the to of an infinitive from the simple form of the

verb that follows. If a word does come between these two components, a split infinitive results. Look

at the example that follows:

Wrong:

Right:

Sara hopes to quickly finish her chemistry homework so that she can return to the more interesting

Stephen King novel she had to abandon.

Sara hopes to finish her chemistry homework quickly so that she can return to the more interesting

Stephen King novel she had to abandon.

Some English teachers believe that thou shall not split infinitives was written on the stone tablets that

Moses carried down from the mountain. Breaking the rule, in their eyes, is equivalent to killing,

stealing, coveting another man's wife, or dishonoring one's parents. If you have this type of English

teacher, then don't split infinitives!

Other folks, however, consider the split infinitive a construction, not an error. They believe that split

infinitives are perfectly appropriate, especially in informal writing.

In fact, an infinitive will occasionally require splitting, sometimes for meaning and sometimes for

sentence cadence. One of the most celebrated split infinitives begins every episode of Star Trek: "To

boldly go where no one has gone before ...." Boldly to go? To go boldly? Neither option is as

effective as the original!

When you are making the decision to split or not to split, consider your audience. If the piece of

writing is very formal and you can maneuver the words to avoid splitting the infinitive, then do so. If

you like the infinitive split and know that its presence will not hurt the effectiveness of your writing,

leave it alone.

T he

Infinitive

Phr ase

An infinitive phrase will begin with an infinitive [to + simple form of the verb]. It will include objects

and/or modifiers. Here are some examples:

To smash a spider

To kick the ball past the dazed goalie

To lick the grease from his shiny fingers d espite the disapproving glances of his

girlfriend Gloria

Infinitive phrases can function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs. Look at these examples:

To finish her shift without spilling another pizza into a customer's lap is Michelle's

only goal tonight.

To finish her shift without spilling another pizza into a customer's lap functions as a noun because it is

the subject of the sentence.

Lakesha hopes to win the approval of her mother by switching her major from fine

arts to pre -med.

To win the approval of her mother functions as a noun because it is the direct object for the verb

hopes.

The best way to survive Dr. Peterson's boring history lectures is a sharp pencil to

stab in your thigh if you catch yourself drifting off.

To survive Dr. Peterson's boring history lectures functions as an adjective because it modifies way.

Kelvin, an aspiring comic book artist, is taking Anatomy and Physiology this semester

to understand the interplay of muscle and bone in the human body .

To understand the interplay of muscle and bone in the human body functions as an adverb because it

explains why Kelvin is taking the class.

Punctuate an infinitive phrase correctly.

When an infinitive phrase introduces a main clause, separate the two sentence components with a

comma. The pattern looks like this:

infinitive phrase +,+main clause.

Read this example:

To avoid burning another bag of popcorn, Brendan pressed his nose against the

microwave door, sniffing suspiciously.

When an infinitive phrase breaks the flow of a main clause, use a comma both before and after the

interrupter. The pattern looks like this:

start of main clause +,+interrupter +,+end of main clause.

Here is an example:

Those basketball shoes , to be perfectly honest, do not complement the suit you are

planning to wear to the interview.

When an infinitive phrase concludes a main clause, you need no punctuation to connect the two

sentence parts. The pattern looks like this:

main clause +Ø+infinitive phrase.

Check out this example:

Janice and her friends went to the mall to flirt with the cute guys who congregate at

the food court.

Day Eight: Adverb and adjective clauses

T he

Adverb

Clause

An adverb clause will meet three requirements:

▪ First, it will contain a subject and verb.

▪ You will also find a subordinate conjunction that keeps the clause from expressing a complete

thought.

▪ Finally, you will notice that the clause answers one of these three adverb questions: How? When?

or Why?

Read these examples:

Tommy scrubbed the bathroom tile until his arms ached.

How did Tommy scrub? Until his arms ached, an adverb clause.

Josephine's three cats bolted from the driveway once they saw her car turn the

corner.

When did the cats bolt? Once they saw her car turn the corner, an adverb clause.

After her appointment at the orthodontist, Danielle cooked eggs for dinner because

she could easily chew an omelet.

Why did Danielle cook eggs? Because she could easily chew an omelet, an adverb clause.

T he

Adverb

Adverbs tweak the meaning of verbs, adjectives, other adverbs, and clauses. Read, for example, this

sentence:

Our basset hound Bailey sleeps on the living room floor.

Is Bailey a sound sleeper, curled into a tight ball? Or is he a fitful sleeper, his paws twitching while he

dreams? The addition of an adverb adjusts the meaning of the verb sleeps so that the reader has a

clearer picture:

Our basset hound Bailey sleeps peacefully on the living room floor.

Adverbs can be single words, or they can be phrases or clauses. Adverbs answer one of these four

questions: How? When? Where? and Why?

Here are some single-word examples:

Lenora rudely grabbed the last chocolate cookie.

The adverb rudely fine-tunes the verb grabbed.

Tyler stumbled in the completely dark kitchen.

The adverb completely fine-tunes the adjective dark.

Roxanne very happily accepted the ten -point late penalty to work on her research

essay one more day.

The adverb very fine-tunes the adverb happily.

Surprisingly, the restroom stalls had toilet paper.

The adverb surprisingly modifies the entire main clause that follows.

Many single-word adverbs end in ly. In the examples above, you saw peacefully, rudely, completely,

happily, and surprisingly. Not all ly words are adverbs, however. Lively, lonely, and lovely are

adjectives instead, answering the questions What kind? or Which one?

Many single-word adverbs have no specific ending, such as next, not, often, seldom, and then. If you

are uncertain whether a word is an adverb or not, use a dictionary to determine its part of speech.

Adverbs can also be multi-word phrases and clauses. Here are some examples:

At 2 a.m., a bat flew through Deidre's open bedroom window .

The prepositional phrase at 2 a.m. indicates when the event happened. The second prepositional

phrase, through Deidre's open bedroom window, describes where the creature traveled.

W ith a fork, George thrashed the raw eggs until they foamed .

The subordinate clause until they foamed describes how George prepared the eggs.

Sylvia emptied the carton of milk into the sink because the expiration date had long

passed.

The subordinate clause because the expiration date had long passed describes why Sylvia poured

out the milk.

Avoid an adverb when a single, stronger word will do.

Many readers believe that adverbs make sentences bloated and flabby. When you can replace a twoword combination with a more powerful, single word, do so!

For example, don't write drink quickly when you mean gulp, or walk slowly when you mean saunter, or

very hungry when you mean ravenous.

Form comparative and superlative adverbs correctly.

To make comparisons, you will often need comparative or superlative adverbs. You use comparative

adverbs—more and less—if you are discussing two people, places, or things. You use superlative

adverbs—most and least—if you have three or more people, places, or things. Look at these two

examples:

Beth loves green vege tables, so she eats broccoli more frequently than her brother

Daniel does.

Among the members of her family, Beth eats pepperoni pizza the least often.

Don't use an adjective when you need an adverb instead.

You will often hear people say, "Anthony is real smart" or "This pizza sauce is real salty."

Real is an adjective, so it cannot modify another adjective like smart or salty. What people should say

is "Anthony is really smart" or "This pizza sauce is really salty."

If you train yourself to add the extra ly syllable when you speak, you will likely remember it when you

write, where its absence will otherwise cost you points or respect!

Realize that an adverb is not part of the verb.

Some verbs require up to four words to complete the tense. A multi-part verb has a base or main part

as well as auxiliary or helping verbs with it.

When a short adverb such as also, never, or not interrupts, it is still an adverb, not part of the verb.

Read these examples:

For his birthday, Frank would also like a jar of dill pickles.

Would like = verb; also = adverb.

After that dreadful casserole you made last night, Julie will never eat tuna or broccoli

again.

Will eat = verb; never = adverb.

Despite the approaching deadline, Sheryl -Ann has not started her research essay.

Has started = verb; not = adverb.

T he

Adjective

Adjectives describe nouns by answering one of these three questions: What kind is it? How many are

there? Which one is it? An adjective can be a single word, a phrase, or a clause. Check out these

examples:

What kind is it?

Dan decided that the fuzzy green bread would make an unappetizing sandwich.

What kind of bread? Fuzzy and green! What kind of sandwich? Unappetizing!

A friend with a fat wallet will never want for weekend shopping partners.

What kind of friend? One with money to spend!

A towel that is still warm from the dryer is more comforting t han a hot fudge sundae.

What kind of towel? One right out of the dryer.

How many are there?

Seven hungry space aliens slithered into the diner and ordered two dozen vanilla

milkshakes.

How many hungry space aliens? Seven!

The students, five f reshmen and six sophomores, braved Dr. Ribley's killer calculus

exam.

How many students? Eleven!

The disorganized pile of books, which contained seventeen overdue volumes from the

library and five unread class texts , blocked the doorway in Eli's dorm room.

How many books? Twenty-two!

Which one is it?

The most unhealthy item from the cafeteria is the steak sub, which will slime your

hands with grease.

Which item from the cafeteria? Certainly not the one that will lower your cholesterol!

The cockroach eyeing your cookie has started to crawl this way.

Which cockroach? Not the one crawling up your leg but the one who wants your cookie!

The students who neglected to prepare for Mrs. Mauzy's English class hide in the

cafeteria rather than risk their instructor's wrath.

Which students? Not the good students but the lazy slackers.

Know how to punctuate a series of adjectives.

To describe a noun fully, you might need to use two or more adjectives. Sometimes a series of

adjectives requires commas, but sometimes it doesn't. What makes the difference?

If the adjectives are coordinate, you must use commas between them. If, on the other hand, the

adjectives are noncoordinate, no commas are necessary. How do you tell the difference?

Coordinate adjectives can pass one of two tests. When you reorder the series or when you insert and

between them, they still make sense. Look at the following example:

The tall, creamy, delicious milkshake melted on the counter while the inattentive

waiter flirted with the pretty cashier.

Now read this revision:

The delicious, tall, creamy milkshake melted on the counter while the inattentive

waiter flirted with the pretty ca shier.

The series of adjectives still makes sense even though the order has changed. And if you insert and

between the adjectives, you still have a logical sentence:

The tall and creamy and delicious milkshake melted on the counter while the

inattentive wa iter flirted with the pretty cashier.

Non coordinate adjectives do not make sense when you reorder the series or when you insert and

between them. Check out this example:

Jeanne's two fat Siamese cats hog the electric blanket on cold winter evenings.

If you switch the order of the adjectives, the sentence becomes gibberish:

Fat Siamese two Jeanne's cats hog the electric blanket on cold winter evenings.

Logic will also evaporate if you insert and between the adjectives.

Jeanne's and two and fat and Siamese cats hog the electric blanket on cold winter

evenings.

Form comparative and superlative adjectives correctly.

To make comparisons, you will often need comparative or superlative adjectives. You use

comparative adjectives if you are discussing two people, places, or things. You use superlative

adjectives if you have three or more people, places, or things. Look at these two examples:

Stevie, a suck up who sits in the front row, has a thicker notebook than Nina, who

never comes to class.

The thinnest notebook belongs to Mike, a computer geek who scans all notes and

handouts and saves them on the hard drive of his laptop.

You can form comparative adjectives two ways. You can add er to the end of the adjective, or you can

use more or less before it. Do not, however, do both! You violate the rules of grammar if you claim

that you are more taller, more smarter, or less faster than your older brother Fred.

One-syllable words generally take er at the end, as in these examples:

Because Fuzz is a smaller cat than Buster, she loses the fights for tuna fish.

For dinner, we ordered a bigger pizza than usual so that we would have cold leftovers

for breakfast.

Two-syllable words vary. Check out these examples:

Kelly is lazier than an old dog; he is perfectly h appy spending an entire Saturday on

the couch, watching old movies and napping.

The new suit makes Marvin more handsome than a movie star.

Use more or less before adjectives with three or more syllables:

Movies on our new flat -screen television are, thankfully, less colorful; we no longer

have to tolerate the electric greens and nuclear pinks of the old unit.

Heather is more compassionate than anyone I know; she watches where she steps to

avoid squashing a poor bug by accident.

You can form superlative adjectives two ways as well. You can add est to the end of the adjective, or

you can use most or least before it. Do not, however, do both! You violate another grammatical rule if

you claim that you are the most brightest, most happiest, or least angriest member of your family.

One-syllable words generally take est at the end, as in these examples:

These are the tartest lemon -roasted squid tentacles that I have ever eaten!

Nigel, the tallest member of the class, has to sit in the front row because he has bad

eyes; the rest of us crane around him for a glimpse of the board.

Two-syllable words vary. Check out these examples:

Because Hector refuses to read directions, he made the crispiest mashed potatoes

ever in the history of instant food.

Because Isaac has a crush on Ms. Orsini, his English teacher, he believes that she is

the most gorgeous creature to walk the planet.

Use most or least before adjectives with three or more syllables:

The most frustrating experience of Desiree's day was arriving home to discover that

the onion rings were missing from her drive -thru order.

The least believable detail of the story was that the space aliens had offered Eli a

slice of pepperoni pizza before his release.

T he

Adjective

Clause

An adjective clause—also called an adjectival or relative clause—will meet three requirements:

▪ First, it will contain a subject and verb.

▪ Next, it will begin with a relative pronoun [who, whom, whose, that, or which] or a relative adverb

[when, where, or why].

▪ Finally, it will function as an adjective, answering the questions What kind? How many? or Which

one?

The adjective clause will follow one of these two patterns:

relative pronoun or adverb +subject +verb

relative pronoun as subject +verb

Here are some examples:

W hose big, brown eyes pleaded for another cookie

Whose = relative pronoun; eyes = subject; pleaded = verb.

W hy Fred cannot stand sitting across from his sister Melanie

Why = relative adverb; Fred = subject; can stand = verb [not, an adverb, is not officially part of the

verb].

That bounced across the kitchen floor

That = relative pronoun functioning as subject; bounced = verb.

W ho hiccupped for seven hours afterward

Who = relative pronoun functioning as subject; hiccupped = verb.

Avoid writing a sentence fragment.

An adjective clause does not express a complete thought, so it cannot stand alone as a sentence. To

avoid writing a fragment, you must connect each adjective clause to a main clause. Read the

examples below. Notice that the adjective clause follows the word that it describes.

Diane felt manipulated by her beagle Santana, whose big, brown eyes pleaded for

another cookie.

Chewing with her mouth open is one reason why Fred cannot stand sitting across

from his sister Melanie .

Growling ferociously, Oreo and Skeeter, Madison's two dogs, competed for the

hardboiled egg that bounced across the kitchen floor .

Laughter erupted from Annamarie, who hiccupped for seven hours afterward .

Punctuate an adjective clause correctly.

Punctuating adjective clauses can be tricky. For each sentence, you will have to decide if the

adjective clause is essential or nonessential and then use commas accordingly.

Essential clauses do not require commas. An adjective clause is essential when you need the

information it provides. Look at this example:

The vegetables that people leave uneaten are often the most nutritious.

Vegetables is nonspecific. To know which ones we are talking about, we must have the information in

the adjective clause. Thus, the adjective clause is essential and requires no commas.

If, however, we eliminate vegetables and choose a more specific noun instead, the adjective clause

becomes nonessential and does require commas to separate it from the rest of the sentence. Read

this revision:

Broccoli, which people often leave uneaten, is very nutritious.

Day Nine: Noun clauses and compound sentences

Parts of a Sentence: The Noun Clause

A clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb. Some clauses are

dependent: they can't stand alone and need an independent clause, or sentence, to

support them.

These dependent clauses can be used in three ways: as adjectives, as adverbs and as

nouns. This article focuses on noun clauses.

What is a noun clause?

A noun clause is a dependent clause that acts as a noun.

What words are signs of a noun clause?

Noun clauses most often begin with the subordinating conjunction that. Other words that

may begin a noun clause are if, how, what, whatever, when, where, whether, which,

who, whoever, whom and why.

What can a noun clause do in a sentence?

Since a noun clause acts as a noun, it can do anything that a noun can do. A noun clause can be a

subject, a direct object, an indirect object, an object of a preposition, a subject complement, an object

complement or an appositive.

Examples:

Whatever you decide is fine with me. (subject of the verb is)

I could see by your bouncy personality that you'd enjoy bungee jumping.

(direct object of the verb

see)

We will give whoever drops by a free Yogalates lesson.

(indirect object of the verb phrase will give)

Lacey talked at length about how she had won the perogy-eating contest.

(object of the preposition

about)

The problem is that my GPS is lost.

(subject complement after the linking verb is)

Call me whatever you like; you're still not borrowing my car.

(object complement referring to object

me)

Al's assumption that bubble tea was carbonated turned out to be false.

(appositive, explaining noun

assumption)

How do noun clauses differ from other dependent clauses?

Other dependent clauses act as adjectives and adverbs. We can remove them and still have a

complete independent clause left, with a subject and verb and any necessary complements.

That is not the case with most noun clauses. A clause acting as an indirect object or an appositive

may be removable, but other types of noun clauses are too essential to the sentence to be removed.

Consider these examples:

Whether you drive or fly is up to you.

I wondered if you would like to go to the barbecue.

Sandy led us to where she had last seen the canoe.

If we remove these noun clauses, what is left will not make much sense:

is up to you

I wondered

Sandy led us to

That is because, in each example, the dependent noun clause forms a key part of the independent

clause: it acts as the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition. Without those key parts,

the independent clauses do not express complete thoughts.

A sentence containing a noun clause is thus the one case in which an “independent” clause may

actually need a dependent clause to be complete!

When are commas needed with a noun clause?

Noun clauses may need to be set off by one or two commas in the following situations.

Appositives

An appositive is a noun, pronoun, or nominal (a word or word group acting as a noun) that is placed

next to a noun to explain it. For example, in the following sentence, the noun phrase the mayor of

Riverton is an appositive explaining who John Allen is:

John Allen, the mayor of Riverton, is speaking tonight.

Noun clauses are nominals and can act as appositives. In that case, they may require commas if they

are not essential to the meaning of the sentence:

I did not believe his original statement, that he had won the lottery, until he proved it to us.

Here, the words his original statement identify which statement is meant, so the noun clause provides

information that is merely additional and not essential.

Compare this sentence to the one below:

I did not believe his statement that he had won the lottery until he proved it to us.

In this case, the noun clause is essential for identifying which statement is meant and therefore takes

no commas.

Unusual position

Other than appositives, noun clauses do not normally require commas. However, if the clause is in an

unusual position, it may require a comma:

That the work was done on time, we cannot deny. (object of verb deny—placed first, instead of after

verb)

BUT