Road to Nowhere: Accounting and Placelessness

advertisement

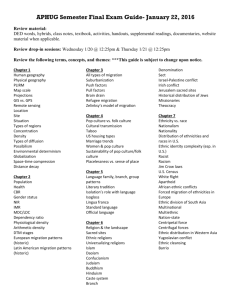

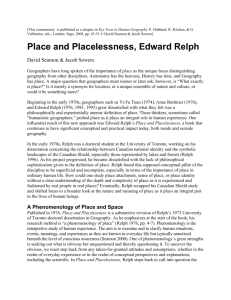

Road to Nowhere: Accounting and Placelessness Elton G. McGoun William H. Dunkak Professor of Finance School of Management Bucknell University Address correspondence to: Elton G. McGoun School of Management Bucknell University Lewisburg, PA 17837 USA +1-570-577-3732 mcgoun@bucknell.edu Road to Nowhere: Accounting and Placelessness Abstract What is “placelessness”, and are global architectural and operational homogeneity sufficient conditions for it? Furthermore, is placelessness a wholly economic phenomenon in which managerial accountants determined to optimize capital investment and minimize operating expenses have become responsible for more and more of the environments that humans are often compelled to inhabit? In truth, we can not indict accounting for producing placeless. It is simply employed to ensure that capital receives the profits it has paid for. What accounting must accept responsibility for, however, is the maintenance of placelessness. Without its controls, a nowhere constructed by capital would evolve and would sooner or later be transformed into a place. Accounting is the conservative force that resists organic change. As accounting is the language in which the activities of the invisible hand are recorded, its rules constrain those activities including their visible and invisible effects on space and on its inhabitants. Road to Nowhere: Accounting and Placelessness I. Introduction By the Philadelphia International Airport, surrounded by runways, taxiways, highways, and highway access ramps, there is a residential island. But it has no permanent residents. Workers arrive and depart daily to staff its three hotels. Hotel guests arrive and depart daily before flights, after flights, or between flights for a short rest or perhaps a brief conference, not having the time or the inclination for a trip into the city. Residents of Philadelphia have no reason to go there unless they’re meeting travelers or are travelers themselves. It is somewhere people do not choose to be but are compelled to be by flight schedules, flight delays, flight cancellations, or business contingencies. It is indisputably convenient and efficient, however. Although there’s a maze of traffic signals, driveways, and entrance gates to navigate in order to get there, once there there’s abundant parking for motorists (only the most courageous pedestrian would attempt to reach the island), and the hotels offer all the necessary amenities for a pleasant stay. The island is an exemplar of the common understanding of “placelessness.” More and more of our lives, it has been argued, take place in spaces that could be anywhere—that look, feel, sound and smell the same wherever in the globe we may be. Fast food outlets, shopping malls, airports, high street shops and hotels are all more or less the same wherever we go. These are spaces that seem detached from the local environment and tell us nothing about the particular locality in which they are located. (Cresswell, 2004, page 43, emphasis added) Along with its near total physical detachment from anywhere else, there is very little about the island to attach it to Philadelphia, to Pennsylvania, or even to the United States. One would anticipate nothing memorable about a stay there that might distinguish it from a stay upon any of hundreds of equivalent residential islands elsewhere in the world. The island’s placelessness appears attributable to the economics of this segment of the hospitality industry. Evidence of cost minimization consistent with an adequate level of comfort during a guest’s limited sojourn is everywhere. Whatever does not assure the sufficiency of an evening’s diversion, a night’s sleep, and a morning’s ablutions is eschewed. Décor is kept to the minimum necessary for the space to be psychologically fit for human habitation. Overall, the space has been designed to be rapidly serviced by minimally-trained (as well as minimally-compensated and minimally-motivated) personnel. Furniture and fixtures are uncluttered, and it is clear when literature or toiletries have been consumed and need to be replaced. However familiar, this assessment of the island’s placelessness is simplistic. What is “placelessness”, and are global architectural and operational homogeneity sufficient conditions for it? Furthermore, is placelessness a wholly economic phenomenon in which managerial accountants determined to optimize capital investment and minimize operating expenses have become responsible for more and more of the environments, like the island, that humans are often compelled to inhabit? The literature on “space” and “place” is voluminous and inconsistent, and Section II summarizes the different ways in which the concept of “place” has been interpreted. This leads to Section III’s exploration of what “placelessness” might mean and where it might come from. Section IV concludes with an assessment of accounting’s role in the apparent burgeoning of placelessness. Is the road to nowhere paved with debits and credits? II. Space and Place Two surveys (Cresswell, 2004; Agnew, 2011) provide excellent comprehensive introductions to the issues surrounding “space” and “place” and how the differing positions on these issues might be situated with respect to each other.1 There has been general agreement that space is a geometrical concept, the undifferentiated two-dimensional area (on a surface) or three-dimensional volume (in, well, space) that exists independent of human activity. A location within space singled out by someone in whatever way for whatever reason is a place. Place is somewhere in space that means something to someone; somewhere to which they are attached, however firmly or tenuously. Nowadays, however, the concept of space must be expanded to incorporate the potentialities of electronically-mediated communication, creating what is familiarly known as cyberspace. Space need not be wholly physical nor must the places within it. “Space isn’t a mere metaphor. The rhetoric and semantics of the Web are those of space. More important, our experience of the Web is fundamentally spatial.” (Weinberger, 2002, page 25) The basic controversy regarding place concerns the ways and the reasons by which and for which someone has singled out a location to be special, that is, what is means or why they are attached to it. At the very minimum is the slight (and likely evanescent) placeness declared by the statement “I am here,” noting that it is as meaningful a statement in cyberspace as in physical space. One might say, then, that humans necessarily transform space into place simply by pausing somewhere in space (Tuan, 1977) and 1 Gieryn (2000) is another interesting survey, from a sociologist rather than a geographer. thereby differentiating that location from all others.2 For place to matter, however, it must mean more than simple presence. So from this point of origin, placeness expands outward in two dimensions. One is depth of meaning (for an individual); the other is communality of meaning (for a group). Depth of meaning is a matter of authenticity or rootedness, that is, what an individual feels about a place. The opposites are of course inauthenticity and rootlessness. [I]nauthentic existence is stereotyped, artificial, dishonest, planned by others, rather than being direct and reflecting a genuine belief system encompassing all aspects of existence. . . . [Inauthenticity] involves a leveling down of the possibilities of being, a covering-up of genuine responses and experiences by the adoption of fashionable mass attitudes and actions. The values are those of mediocrity and superficiality that have been borrowed or handed down from some external source. (Relph, 1976, page 81) Communality of meaning is a matter of the ongoing social, political, and economic processes through which meaning is socially constructed, that is, what a group makes of a place for the members of the group.3 [P]lace is constituted through reiterative social practice—place is made and remade on a daily basis. Place provides a template for practice—an unstable stage for performance. Thinking of place as performed and practiced can help us think of place in radically open and non-essentialized ways where place is constantly struggled over and reimagined in practical ways. (Cresswell, 2004, page 39) In short, people are their place and a place is its people, and however readily these may be separated in conceptual terms, in experience they are not easily differentiated. In this context places are ‘public’—they are created and known through common experiences and involvement in common symbols and meanings. (Relph, 1976, page 34) One might relate to a place as either an insider or outsider, who differ in the depth of the meaning a place has for them4, and meaning, however deep or shallow, is a personal attribute of a place accessible Sack (1997) and Casey (2001) go farther regarding the elemental connection between personhood and place. “Places need the actions of people or selves to exist and have effect. The opposite is equally true— selves cannot be formed and sustained or have effect without place.” (Sack, 1997, page 88) And: “The relationship between self and place is not just one of reciprocal influence . . . but also, more radically, of constitutive coingredience: each is essential to the being of the other. In effect, there is no place without self and no self without place.” (Casey, 2001, page 684, italics in original) 3 A number of books describe this process in rich—and often personal—detail, including Hiss (1990), Hayden (1995), and Lippard (1997). 4 “The essence of place lies not so much in these as in the experience of an ‘inside’ that is distinct from an ‘outside’; more than anything else this is what sets places apart in space and defines a particular system of physical features, activities, and meanings. To be inside a place is to belong to it and to identify with it, 2 only to the individual for whom the place has that meaning. Landscape, however, consists of material attributes of a place accessible to everyone—the sights, the sounds, the smells, etc. of the place itself along with their media representations.5 Placeness, then, is not only psycho-social (phenomenological) but also sensory (cognitive). There are certainly complex and profound interactions and interdependencies between meaning and landscape—landscape can be crafted in response to meaning (i.e. construction of a commemorative monument), and meaning can be responsive to changes in landscape (i.e. destruction of a historic landmark)—but the two have no necessary connections. The most banal landscape can have the deepest meaning for an insider, and the most dramatic and distinctive one only the shallowest for an outsider. Nonetheless, they are places for both. A consequence of these concepts of place is that there can be no such thing as absolute placelessness. [Place] is a construction of humanity but a necessary one—one that human life is impossible to conceive of without. In other words there was no ‘place’ before there was humanity but once we came into existence then place did too. A future without place is simply inconceivable. . . . [P]lace is a kind of ‘necessary social construction’—something we have to construct in order to be human. (Cresswell, 2004, page 33) Yet there is no shortage of indictments that humanity is travelling along a “road to nowhere” towards a future of greater placelessness. What might this mean? III. Placelessness Casey (1993) points out that the literal meaning of the Greek word atopos, which we translate as “bizarre” or “strange”, is “no place.” Augé provides a somewhat generic definition: “If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place.” (Augé, 1995, page 77) From the preceding discussion of place, one can extract at least four sources of what might be referred to as placelessness, which are in fact quite common and not necessarily what we might regard as bizarre or and the more profoundly inside you are the stronger is this identity with the place. . . . From the outside you look upon a place as a traveller might look upon a town from a distance; from the inside you experience a place, are surrounded by it and part of it. The inside-outside division thus presents itself as a simple but basic dualism, one that is fundamental in our experiences of lived-space and one that provides the essence of place.” (Relph, 1976, page 49) 5 This is a more inclusive definition than usual of the term “landscape,” which is commonly limited to the visual. Here it incorporates the less familiar term “soundscape” (auditory) and the still less familiar term “smellscape” (olfactory). strange: electronic placelessness, existential placelessness, aesthetic placelessness, and placeful placelessness. Although the language of place along with the practices that create places can be applied to cyberspace, electronically-mediated communication generates a placeness quite different from placeness within geometric space. A common sense of what “place” is that it is the answer to the question “Where?” But how does someone using an electronic device answer that question for the person with whom they are engaged in a meaningful but dematerialized interaction? Perhaps the earliest analysis of electronic placelessness is Meyrowitz’ (1985) No Sense of Place, which despite its having preceded the Internet and social media is still an important work on the subject. In it, Meyrowitz makes the distinction between physical place and social place. Although society can transform space into place as described in the preceding section, place can then transform society, in the sense that where you are shapes what you are, that is, how you behave. This feedback loop is driven by information; what you are is a consequence of what you and others know about yourself and others. Before electronic media, information was associated with physical place. What (and whom) you knew was limited by where you were, a connection that has been severed. Now that what we are is much less shaped by where we are (given the traditional understanding of the answer to the question “Where?”), we might not have lost our sense of (physical) place, but we do have a very different—and undoubtedly attenuated—one. Electronic placelessness, however, is purely driven by technology, and it is a very different phenomenon from the other three, in which accounting is likely to play a more prominent role. Lippard (1997) provides the most succinct definition of placelessness: “place ignored, unseen, or unknown.” (Lippard, 1997, page 9) Although she does not use the term, this is existential placelessness. As fewer remain anywhere long enough to set down roots or to engage in the communal social, political, and economic processes to construct meaning—or for that matter to attend to where they are at all— meaningful placeness is inhibited. In other words, we come to inhabit—or exist in—space and not place. As we move along the earth we pass from one place to another. But if we move quickly the places blur; we lose track of their qualities, and they may coalesce into the sense that we are moving through space. (Sack, 1997, page 16) Aesthetic placelessness is the sort claimed for the Philadelphia hotel island described in the introduction. It may indeed be that “[t]he traveler’s space may thus be the archetype of non-place.” (Augé, 1995, page 86) and “. . . non-places are there to be passed through. . .” (Augé, 1995, page 104) When the landscape of everywhere becomes the same as that of everywhere else, there is less differentiated, meaningful placeness anywhere. Without specifically discussing “place,” the novelist James Howard Kunstler (1993) delivers his interpretation of the literal “development” of American aesthetic placelessness in the aptly titled book The Geography of Nowhere in which he coined the term “crudspace” for exemplars of aesthetic placelessness.6 With reference to the preceding section, then, existential placelessness is psycho-social (phenomenological) in which space is meaningless and aesthetic placelessness is sensory (cognitive) in which space is featureless. Placeful placelessness is the result of self-conscious efforts to create places, which efforts fail to do so by the very determination by which they are undertaken. In the same vein as “truthiness,” which is a truth unsupported by anything but the desire that it be true (Armstrong, 2012), this might be called “placiness.” In effect, it is an extension of the “staged authenticity” familiar at tourist sites like historical reconstructions/re-creations such as Williamsburg (Sack, 1992) or so-called “pseudo-places” such as Disneyland (Relph, 1976), but for the “benefit” of the inhabitants and not visitors. The “New Urbanism”—exemplified by the towns of Celebration and Seaside in Florida, Poundbury in Dorset, and Noorderhof and Brandevoort De Veste in the Netherlands among others—intends to create real communities with real placeness, unlike the aesthetic placelessness of the stereotypical suburb. (Ross, 2000; Frantz and Collins, 2000; Bartling, 2002; Mohney and Keller, 1996; Hardy, 2005; Meier and Karsten, 2012) In doing so, however, some contend that these are artificial places that have simply replaced one form of placelessness with another.7 However, charges of rampant placelessness, in whichever of these four ways, might be exaggerated. One might argue that much of the criticism can be attributed to a nostalgic, conservative— and outmoded—image of place as a site of individual and group stability, a stability which is inherently exclusionary.8 What some deride as placelessness might well be a less stable—but more adaptable— placeness that demands something more (or perhaps something different) of the inhabitant to appreciate its psycho-social (existential) and material (aesthetic) attributes. Both placeless and placelessness are to a greater or lesser extent in the eye (and mind) of the beholder. Perhaps a more important caveat to bear in mind is that a rich place does not emerge full-blown out of space like Athena from the head of Zeus. Both the meaning and the landscape of a place had to have grown and developed over some time during its lifespan. A nascent place may appear to be placeless simply because it was only recently carved out of space. It has also been referred to as “junkspace” by the architect Rem Koolhaas (2001), which term was expanded upon in Jameson (2003) 7 One might also include certain businesses as exhibiting placeful placelessness in a similar way. (Buchanan, 2005, page 29) “Chains such as Starbucks are scariest of all, because they impersonate the sensibility [i.e. placeness] of the nonchains, while McDonald’s is at least honest about its mass-production values. . . . [T]o step into any [Starbucks] is to enter limbo, albeit limbo with good graphic design. ” (Solnit and Schwartzenberg, 2000, page 141) 8 “For others, a ‘retreat to place’ represents a protective pulling-up of drawbridges and a building of walls against the new invasions. Place, on this reading, is the locus of denial, of attempted withdrawal from invasion/difference. It is a politically conservative haven . . .” (Massey, 2005, page 5) 6 Granting, however, that there is such a thing as placelessness, that is, “nowhere,” where does the road that ends there originate? Often sources locate it in an unspecified process of “globalization” in strikingly similar terms: It is commonplace in Western societies in the twenty-first Century to bemoan a loss of a sense of place as the forces of globalization have eroded local cultures and produced homogenized global space. (Cresswell, 2004, page 8) Or as Arefi (1999) puts it, “[G]lobalization in general weakens local ties and fosters homogeneity and sameness based on the tenets of consumerism and capital mobility.” (Arefi, 1999, page 190) In these quotations, the authors suggest aesthetic placelessness with the words “homogenized” and “homogeneity” and existential placelessness with the phrases “eroded local cultures” and “weakens local ties”. However, just what “globalization” and more specifically “global capital and consumerism” are and just how they destroy place is never specified, as if the terms themselves with their familiar pejorative connotations are sufficiently explanatory.9 For example: Factories and fields, schools, churches, shopping centres and parks, roads and railways litter a landscape that has been indelibly and irreversibly carved out according to the dictates of capitalism. (Harvey, 1982, page 373) The globalization of capitalism has been associated with industrialization. Industrialization has, in turn, been associated with urbanization, the settlement patterns that emerged with the concentration of industry after an initial period of dispersion. The process of urbanization has been seen as destructive of traditional patterns of life and thus also destructive of the diversity of ways of life or cultural forms. It has also been associated with the standardization of landscapes . . . (Entrikin, 1991, page 31) Labor markets and consumer services markets demanding interpersonal interaction remain largely local and more likely embedded in place. Impersonal capital markets, goods markets, and business services markets are increasingly global and detached from place. However, these latter markets have always been significantly global, and no one has attempted to correlate the progress of such globalization with that of placelessness and establish a clear cause and effect relationship between the two. That neither “globalization” nor “placelessness” can be easily defined let alone measured makes it unlikely that this is even possible. 9 Harvey (1996) refers to this generic academic globalization as “globaloney.” One might associate globalization with an apparent acceleration in the mobility of capital, products, people, ideas, etc.,10 which mobility has already been suggested as a source of existential placelessness. The more quickly capital, products, people, and ideas these move through a place, the less opportunity there is for stable meanings and stable landscapes to grow and develop and the more opportunity there is for existing meanings and existing landscapes to deteriorate. It becomes more difficult for places to grow to maturity and survive there. That capital in particular literally flies at the speed of light is indisputable. In the era of high-frequency trading it might land in someone’s account somewhere for only a few milliseconds, never really materializing before taking off again. If all goes according to plan—and it usually does—this mobile capital deposits a sliver of profit like the disembodied smile of the Cheshire Cat with everyone who hosts it, however briefly, as long as they have skillfully positioned themselves along its flight path. One can easily envision capital roaming more rapidly and unrestrainedly from place to place replacing meaningful commercial transactions with standardized exchanges (existential placelessness) and leaving nothing but homogeneous detritus (aesthetic placelessness) or inauthentic concoctions (placeful placelessness) in its wake. Eventually, though, financial capital must immobilize itself someplace in space in the form of real assets, however homogeneous or inauthentic. Otherwise, it is wholly sterile, unable to produce profit for anyone. 11 As often as the stocks and bonds of its parent corporation might change hands, they are ultimately dependent upon that hotel on the island by the Philadelphia International Airport. And people must always be someplace, which can be in that same hotel on the island by the Philadelphia International Airport. IV. Accounting and Placelessness There is indeed a causal connection between global capital and placelessness, but it has nothing to do with capital’s being globally mobile. According to Walzer (1986), a non-place (or nowhere) is singleminded, whereas a place is open-minded. This means that non-places are designed to perform specific functions. The hotel on the island by the Philadelphia International Airport, for example, was constructed to fulfill the very specific (i.e. very limited) needs of a very specific group of travelers. In contrast, a place “Mobility climbs to the rank of the uppermost among the coveted values—and the freedom to move, perpetually a scarce and unequally distributed commodity, fast becomes the main stratifying factor of our late-modern or postmodern times. All of us are, willy-nilly, by design or by default, on the move. We are on the move even if, physically, we stay put: immobility is not a realistic option in a world of permanent change.” (Bauman, 1998, page 2) 11 Although Harvey (1996) speaks as if there are two sorts of capital—financial and real—it is all the same stuff. Like an aircraft, however, as long as it might spend in the air, capital must eventually land. 10 is occupied by a variety of individuals engaged in a variety of activities imagined and organized organically by the individuals themselves and not by someone else in advance. Central Park in New York City, designed by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux, is a place that has been used since 1873 in many ways by many individuals for whom it means many things, very few of which the designers anticipated or indeed would even have been able to anticipate. Global capital flows are driven towards profits, and one might say that they are driven along the road to nowhere because a single-minded nowhere performs a specific function for which it is possible to calculate and monitor profits through appropriate accounting systems and controls. Were an investment to be open-minded, entailing existential and aesthetic concerns arising from among its inhabitants, its profitability would be impaired. If the hotel on the island by the Philadelphia International Airport spontaneously began being used for the unanticipated activities characteristic of places (for example, picnics, demonstrations, exhibitions, festivals, etc.) its costs and benefits would not be so easy to assess and weigh against each other. Placeful placelessness is a consequence of attempts to accommodate existential and aesthetic concerns, but this merely expands the boundaries of singlemindedness without transcending them. Numerous problems unforeseen by Disney planners arose when Celebration, Florida was populated with real people. (Ross, 2000; Frantz and Collins, 2000; Bartling, 2002) At this point we can not indict accounting for producing placeless. It is simply employed to ensure that capital receives the profits it has paid for. It’s the limited perspective of capital that bears a large part of the guilt for existential and aesthetic placelessness and the somewhat broader—but still circumscribed—perspective of somewhat more enlightened capital that is responsible for placeful placelessness. What accounting must accept responsibility for, however, is the maintenance of placelessness. Without its controls, a nowhere constructed by capital would evolve and would sooner or later be transformed into a place. Accounting is the conservative force that resists organic change. It prevents the hotel on the island by the Philadelphia International Airport for becoming anything other that what it was designed to be. Chefs never tweak the recipe of an entrée. Housekeepers never leave an extra towel in the room. Landscapers never plant a few more decorative impatiens. One might also look at this from the perspective of Lowi that “modern industrialized society can be explained as an effort to make the ‘invisible hand’ as visible as possible.” (Lowi, 1979, page 15) As accounting is the language in which the activities of the invisible hand are recorded, its rules constrain those activities including their visible and invisible effects on space and on its inhabitants. “Leveleddown places of the sort with which we are surrounded today put the self to the test, tempting it to mimic their tenuous character by becoming an indecisive entity incapable of the kind of resolute action that is required in a determinately structured place . . . .” (Casey, 2001, page 685) Bibliography Agnew, John A., “Space and Place,” in The SAGE Handbook of Geographical Knowledge, ed. John A. Agnew and David N. Livingstone, (London: Sage Publications Ltd., 2011), pages 316-330. Arefi, Mahyar, “Non-Place and Placelessness as Narratives of Loss: Rethinking the Notion of Place,” Journal of Urban Design, Volume 4, Number 2, (June, 1999), pages 179-193. Armstrong, Elizabeth, MO/RE/RE/AL: Art in the Age of Truthiness, (New York: Prestel Publishing, 2012). Augé, Marc, Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, (London: Verso, 1995). Bartling, Hugh E., “Disney’s Celebration, the Promise of New Urbanism, and the Portents of Homogeneity,” The Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 81, Number 1, (Summer, 2002), pages 44-67). Bauman, Zygmunt. Globalization: The Human Consequences, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998). Buchanan, Ian, “Space in the Age of Non-Place,” in Deleuze and Space, ed. Ian Buchanan and Gregg Lambert, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), pages 16-35. Casey, Edward S., Getting Back into Place: Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place-World, (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1993). Casey, Edward S., “Between Geography and Philosophy: What Does It Mean to Be in the Place-World?” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Volume 91, Number 4, (2001), pages 683-693. Cresswell, Tim, Place: A Short Introduction, (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 2004). Entrikin, J. Nicholas, The Betweenness of Place: Towards a Geography of Modernity, (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991). Frantz, Douglas and Catherine Collins, Celebration, U.S.A.: Living in Disney’s Brave New Town, (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2000). Gieryn, Thomas F., “A Space for Place in Sociology,” Annual Review of Sociology, Volume 26, (2000), pages 463-496. Hardy, Dennis, Poundbury: The Town that Charles Built, (London: Town & Country Planning Association, 2005). Harvey, David, The Limits to Capital, (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1982). Harvey, David, Justice, Nature & the Geography of Difference, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1996) Hayden, Dolores, The Power of Place, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995). Hiss, Tony, The Experience of Place, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1990). Jameson, Fredric, “Future City,” New Left Review, Volume 21, (May-June, 2003), pages 1-9. Koolhaas, Rem, “Junkspace,” in Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping, ed. Chuihua Judy Chung and SzeTsung Leong, (Köln: Taschen GmbH, 2001), pages . Kunstler, James Howard, The Geography of Nowhere, (New York: Touchstone, 1993). Lippard, Lucy R., The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, (New York: The New Press, 1997). Lowi, Theodore J., The End of Liberalism: The Second Republic of the United States, (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1979). Massey, Doreen, For Space, (London: Sage Publications, 2005). Meier, Sabine and Lia Karsten, “Living in Commodified History: Constructing Class Identities in Neotraditional Neighbourhoods,” Social & Cultural Geography, Volume 13, Number 5, pages 517-535. Meyrowitz, Joshua, No Sense of Place, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). Mohney, David, and Keller Easterling, editors, Seaside: Making a Town in America, (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996). Relph, E. Place and Placelessness, (London: Pion Limited, 1976). Ross, Andrew, The Celebration Chronicles: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Property Value in Disney’s New Town, (New York: Ballantine Books, 2000). Sack, Robert David, Place, Modernity, and the Consumer’s World, (Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992). Sack, Robert David, Homo Geographicus, (Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997). Solnit, Rebecca and Susan Schwartzenberg, Hollow City: The Siege of San Francisco and the Crisis of American Urbanism , (London: Verso, 2002). Tuan, Yi-Fu, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977). Walzer, Michael, “Pleasures and Costs of Urbanity,” Dissent, Volume 33, Number 4, (Fall, 1986), pages 470-475. Weinberger, David, Small Pieces Loosely Joined: A Unified Theory of the Web, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Publishing, 2002).