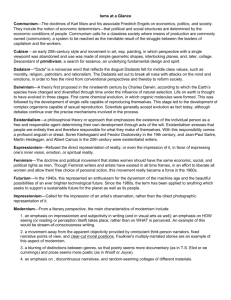

Marxism and Ethics part one - Democratic Socialist Alliance

advertisement