FDR and the New Deal Reading By 1932, one of the bleakest years

advertisement

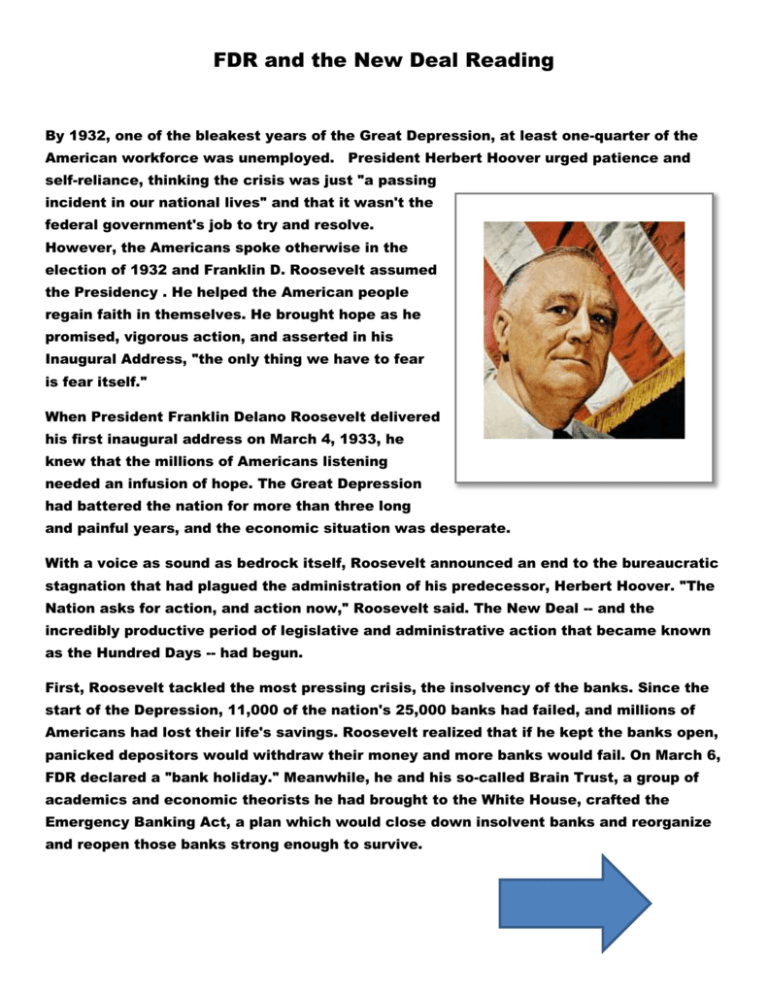

FDR and the New Deal Reading By 1932, one of the bleakest years of the Great Depression, at least one-quarter of the American workforce was unemployed. President Herbert Hoover urged patience and self-reliance, thinking the crisis was just "a passing incident in our national lives" and that it wasn't the federal government's job to try and resolve. However, the Americans spoke otherwise in the election of 1932 and Franklin D. Roosevelt assumed the Presidency . He helped the American people regain faith in themselves. He brought hope as he promised, vigorous action, and asserted in his Inaugural Address, "the only thing we have to fear is fear itself." When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered his first inaugural address on March 4, 1933, he knew that the millions of Americans listening needed an infusion of hope. The Great Depression had battered the nation for more than three long and painful years, and the economic situation was desperate. With a voice as sound as bedrock itself, Roosevelt announced an end to the bureaucratic stagnation that had plagued the administration of his predecessor, Herbert Hoover. "The Nation asks for action, and action now," Roosevelt said. The New Deal -- and the incredibly productive period of legislative and administrative action that became known as the Hundred Days -- had begun. First, Roosevelt tackled the most pressing crisis, the insolvency of the banks. Since the start of the Depression, 11,000 of the nation's 25,000 banks had failed, and millions of Americans had lost their life's savings. Roosevelt realized that if he kept the banks open, panicked depositors would withdraw their money and more banks would fail. On March 6, FDR declared a "bank holiday." Meanwhile, he and his so-called Brain Trust, a group of academics and economic theorists he had brought to the White House, crafted the Emergency Banking Act, a plan which would close down insolvent banks and reorganize and reopen those banks strong enough to survive. The speed with which the Emergency Banking Act bill was written, passed by Congress, and put into practice typified the frenetic pace of the Hundred Days. Roosevelt delivered a draft of the act to the House of Representatives on March 9. The House passed the bill in less than 40 minutes, without any debate. By evening, the bill had passed the Senate as well, and was delivered to the White House for Roosevelt's signature. Newly reorganized banks began opening on March 12 -- by the following day, deposits at these banks exceeded withdrawals. The banking system had been saved. Often thought of today as a "tax-and-spend" liberal, Roosevelt was in fact deeply committed to a balanced budget. He presented Congress with the Economy Act, a bill that put the federal government on a spending diet by cutting the salaries of federal employees, scaling back defense spending, and reducing veterans' pensions. Vets and military men briefly stalled the bill, but it passed on March 15. These early economic reforms did little to solve the problem of massive unemployment. Shuttered-up businesses lined America's main streets. The smokestacks of the factories and mills, which had provided a day's work and a steady paycheck to millions of workers, lay dormant. Roosevelt wanted to do more.