Enforcing International Agreements: What

advertisement

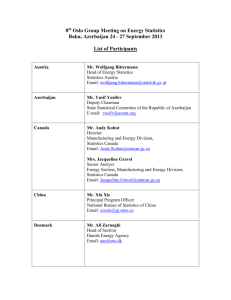

A Theory of Enforcement, Participation, and Compliance in International Environmental Agreements Jon Hovi1 and Stine Aakre2 Department of Political Science, University of Oslo Box 1097 Blindern, 0317 Oslo, Norway and Center for International Climate and Environmental Research – Oslo (CICERO) jon.hovi@stv.uio.no Center for International Climate and Environmental Research – Oslo (CICERO) Box 1129 Blindern, 0318 Oslo, Norway s.y.aakre@cicero.uio.no 1 Abstract The managerial and enforcement schools disagree sharply on whether deep international environmental agreements (IEAs) require enforcement. We combine assumptions from both schools into a single theoretical framework which entails interesting implications about when enforcement enhances compliance and participation in deep IEAs. Some of these implications are in keeping with the managerial school, others are in keeping with the enforcement school, and yet others have typically been ignored by both schools: First, circumstances exist under which all participating countries will comply regardless of whether compliance is enforced. Second, circumstances exist under which some participating countries will comply only if compliance is enforced. Third, some countries will participate only if participation is enforced. Fourth, circumstances exist under which enforcing participation will cause the number of noncompliant countries to increase. Fifth, achieving full participation and full compliance requires that both compliance and participation be enforced. Finally, our theory entails a novel explanation of why noncompliance with IEAs is rare. We use a formal model to develop and clarify the argument. Acknowledgement We are indebted to Knut Alfsen, Guri Bang, Cathrine Hagem, Leif Helland, Bjart Holtsmark, Sjur Kasa, Tora Skodvin, Olav Schram Stokke, and Andreas Tjernshaugen for helpful comments. Frank Azevedo provided excellent editorial assistance. 1 This version: 12 January 2009 1. Introduction Do international environmental agreements (IEAs) require enforcement? Two main schools answer this question differently.1 On one hand, the enforcement school stresses the importance of coercive means such as reciprocal measures,2 financial penalties, trade restrictions, and suspension of privileges (Downs et al. 1996, Barrett & Stavins 2003:362ff.).3 On the other hand, the managerial school considers that “the effort to devise and incorporate [coercive measures] in treaties is largely a waste of time” (Chayes & Chayes 1995:2), and instead proposes a facilitative approach based on capacity building, technical assistance, and transparency (Chayes & Chayes 1993, 1995). These highly diverging views are rooted in contending ideas of what ultimately motivates states’ behavior. While the enforcement school assumes that behavior is guided by a “logic of consequentiality”, the managerial school assumes that behavior is also motivated by a “logic of appropriateness”. Unsurprisingly, the two schools are widely conceived of as rivals and mutually incompatible. As Raustiala and Victor say (1998: 681), they “reflect different visions of how the international system works, the possibilities for governance with international law, and the policy tools that are available and should be used to handle implementation problems”. In contrast, we argue that the two views are best seen as complementary approaches to understanding the relationship between enforcement, compliance, and participation. Whereas previous research has mostly considered compliance and participation separately, we provide a novel theoretical framework that (1) combines assumptions from both schools, and (2) enables us to analyze jointly the circumstances under which countries participate in and comply with IEAs. In a step towards bridging the gap between the two schools we assume that the international system consists of two types of countries: Motivated by norms, type 1 countries participate in and comply with IEAs regardless of whether doing so is in their selfinterest. Motivated by self-interest, type 2 countries participate in and comply with IEAs only 1 Some scholars distinguish three or more explanatory models of compliance; see Underdal (1998) and Breitmeier et al. (2007). 2 For example, the prospect that other countries will retaliate in kind might deter free-riding (Axelrod & Keohane 1986). 3 Incentives for participation and compliance can also be created through positive measures, including side payments, issue linkages, and the allocation/allocations of entitlements such as emission permits (Barrett and Stavins 2003: 360). As argued by Breitmeier et al. (2006: 148–149), there is much to be said for broadening the definition of enforcement to include positive as well as negative incentives. 2 when this maximizes their utility. We show that this theoretical framework entails interesting predictions about when enforcement enhances compliance and participation: First, circumstances exist under which all participating countries will comply regardless of whether compliance is enforced. This prediction is in keeping with the managerial school. Second, circumstances exist under which some participating countries will comply only if compliance is enforced. This prediction is in keeping with the enforcement school. Third, some countries will participate only if participation is enforced. This prediction is also in keeping with the enforcement school, even though both schools have so far been mostly concerned with compliance. Fourth, circumstances exist under which enforcing participation will cause the number of noncompliant countries to increase. Fifth, achieving full participation and full compliance requires that both participation and compliance be enforced. The fourth and fifth predictions have been ignored by both schools. Finally, our theory provides a novel explanation of Henkin’s oft-cited observation that “almost all nations observe almost all principles of international law and almost all of their obligations almost all of the time (Henkin 1979:47).”4 In section 2 we review previous research on participation in and compliance with IEAs. In section 3 we discuss our main research question: When will enforcement induce countries to participate in and comply with IEAs? In section 4 we develop and analyze a formal model which enables us to deepen our argument. A weakness of existing formal models in this field is that they typically consider only either participation (while assuming compliance levels to be determined exogenously) or compliance (while assuming participation levels to be determined exogenously). By contrast, in the model presented and analyzed here, both participation and compliance are determined endogenously. In section 5 we comment briefly on three limitations of our theory. We also provide a policy recommendation. Finally, in section 6 we conclude. 2. Previous Research Both the managerial school and the enforcement school start from the premise that − because of the anarchical nature of the international system − there are no ways countries can 4 We henceforth refer to this observation as “Henkin’s dictum”. 3 guarantee to honour their commitments (Axelrod & Keohane 1986, Oye 1986).5 Hence, both schools see it as essential to map features permitting countries to bind themselves to mutually beneficial courses of action; and both schools find it essential to identify strategies that might enhance cooperation. They also agree that compliance with IEAs has generally been good (cf. Henkin’s dictum) and that enforcement has apparently played little or no role in achieving that record (Chayes & Chayes 1993, Downs et al. 1996, Jacobson & Brown Weiss 1998). However, there are at least three sources of disagreement between the two schools (Tallberg 2002). First, they disagree on whether enforcement influences compliance. The managerial school considers enforcement to be largely irrelevant, and argues that states’ “general propensity to comply” with IEAs is due more to efficiency, national interests, and regime norms (Chayes & Chayes 1995). In contrast, the enforcement school contends that compliance in deep IEAs can be ensured by enforcement measures that offset the benefits a state could obtain by not complying. It argues that widespread compliance despite little enforcement is only to be expected, given that states are generally reluctant to accept obligations they are unable or unwilling to meet.6 Thus, treaties are often shallow, in the sense that they commit countries to little more than they would be prepared to do unilaterally, and such shallow treaties entail little incentive for noncompliance.7 According to the enforcement school it would be a mistake to infer from high compliance to shallow treaties without enforcement that high compliance can also be achieved for deep treaties without enforcement.8 Second, the two schools disagree on what to make of those relatively few instances of noncompliance which are observed. For the managerial school, cases of noncompliance are usually not attempted free-riding through deliberate defiance of the legal standard. Rather, such cases are caused by: (1) the ambiguity and indeterminacy of treaties, (2) the limited capacity of states to comply, and (3) social and economic changes due to time lags between commitments and their implementation. In contrast, the enforcement school argues that the causes of noncompliance are to be found in the incentive structure: states choose to be 5 For a more comprehensive review of the literature on international compliance see Raustiala & Slaughter (2002). 6 While international law requires states to comply with agreements to which they choose to be a party, it does not require states to become a party in the first place (Barrett & Stavins 2003). 7 See Victor (1998) for a similar interpretation. 8 According to this view, the managerial school’s claim that enforcement is largely futile is based on a biased selection of cases and suffers from endogeneity problems. 4 noncompliant when the benefits of noncompliance exceed the costs of being detected and punished. Finally, these two sources of disagreement have implications for what the two schools see as potential remedies for avoiding noncompliance and re-establishing compliance. According to the enforcement school, “a punishment strategy is sufficient to enforce a treaty when each side knows that if it cheats it will suffer enough from the punishment that the net benefit will not be positive” (Downs et al. 1996: 385). In contrast, the managerial school argues that noncompliance is better addressed by: (1) improving dispute resolution procedures, (2) supplying technical and financial assistance, and (3) increasing transparency. Thus, the managerial school sees regimes as playing an “active role...in modifying preferences, generating new options, persuading the parties to move toward increasing compliance with regime norms, and guiding the evolution of the normative structure in the direction of the overall objectives of the regime” (Chayes & Chayes 1995:229). To summarize, the managerial and enforcement schools disagree sharply on whether enforcement matters. Moreover, while these two schools are part of a large literature focusing on compliance, the literature on participation is surprisingly limited and mostly considers participation separately from compliance. We agree with Barrett (1999a, 2005) that compliance and participation are joint problems that should therefore be analyzed jointly. In the next section we develop a theoretical framework that: (1) combines assumptions from both schools and (2) determines the levels of both compliance and participation endogenously. This framework enables us to analyze when enforcement enhances compliance or participation, or both. 3. When Does Enforcement Enhance Participation and Compliance? Assume that countries are motivated by two factors when making decisions about whether to participate in and comply with an IEA aiming to provide a global public good. The first is self-interest, the economic and environmental effects entailed by such decisions for that country. The second factor is the norm that countries should participate in and comply with IEAs regardless of whether doing so is in their self-interest. The motivating force of these two factors may vary between issue areas, over time, and across countries. In issue areas such as climate change, participating in and complying with an IEA might entail substantial 5 adverse economic effects and only limited positive environmental effects. Self-interest might therefore strongly tempt countries to stay out of IEAs and to drag their feet by not complying should they decide to participate. Consequently, the norm to participate and comply needs to be strong to counterbalance the motivating force of self-interest. In contrast, in issue areas such as ozone depletion, where participating in and complying with an IEA might entail relatively small economic costs, norms might be a more prominent factor. As Mitchell (2005:65) points out, “if compliance is easy for the country complying but non-compliance is expensive to the environment and other countries, then non-compliance is likely to be increasingly viewed as deserving of social opprobrium.” In a given issue area, the motivating force of norms might change over time for some or all countries. IEAs often reflect and embed existing norms, but can also “develop and strengthen norms that did not exist previously” (Chayes et al. 1998: 42) through factors such as social learning and socialization (Checkel 2001). Finally, while self-interest might be the more important factor for some countries, norms might be the stronger motivation for other countries. Economic, political, and cultural variables might influence whether a country is predominantly motivated by self-interest or by norms. To keep things simple, we will consider a world consisting of only two types of countries9: Motivated by norms, type 1 countries will participate in and comply with an IEA regardless of whether doing so is in their self-interest.10 Motivated by self-interest, type 2 countries will participate in and comply with the IEA only provided that doing so maximizes their utility. Let N be the total number of countries and let z be the number of type 1 countries, so that N - z is the number of type 2 countries. Assume that four options exist concerning an IEA that will provide a pure public good such as mitigation of climate change or ozone depletion for these N countries. Option 1 is an IEA that 9 See Mitchell (2005) for a similar approach. Our typology is necessarily simplistic. See Elster (1989a, b) for a thorough discussion of self-interest and social norms as motivational forces. 10 Although Chayes & Chayes are primarily occupied with compliance, they seem to believe that forces motivating states to comply also will motivate (most) countries to participate: “Only the largest of states can pretend to significant autonomy in the pursuit of national goals and interests. For the rest, a major index of sovereignty and importance as a nation playing on the international scene is participating in the network of international organizations and agreements that define international life. National decisions may reflect not only an instrumental cost-benefit analysis but the need to be a real participant in international affairs. If a state authenticates itself by membership in the major treaty ‘clubs’ getting in and staying in generates pressures for acceptable compliance with treaty obligations, quite apart from the material benefits produced by the organization” (Chayes & Chayes 1991: 320–321). 6 enforces neither participation nor compliance. Option 2 is an IEA that enforces compliance, but not participation. Option 3 is an IEA that enforces participation but not compliance. Finally, option 4 is an IEA that enforces both compliance and participation. We assume that all options entail non-trivial costs for participating and compliant countries, meaning that we consider only IEAs that are deep in the sense of Downs et al. (1996). We also assume that even a noncompliant participating country contributes something to the public good, and that this contribution entails a cost. In contrast, non-participating countries simply continue business as usual. Given these assumptions, what conditions exist (if any) under which enforcement will enhance compliance or participation, or both? We first provide point predictions for each of the four options regarding: (1) the number of countries that will participate and (2) the number of participating countries that will comply. Next, by comparing these point predictions across options we offer directional predictions of when enforcement will enhance participation or compliance, or both. Finally, we propose a novel explanation of Henkin’s dictum. Point Predictions First, consider an IEA that enforces neither compliance nor participation (option 1). Because the IEA provides a pure public good, a non-participating country will enjoy whatever amount of the good provided by others, without bearing any cost. Moreover, by assumption there is no enforcement of participation and hence no punishment for non-participation. Therefore, the utility-maximizing course of action is non-participation. Accordingly, all type 2 countries will not participate in the IEA. In contrast, all type 1 countries will participate in and comply with the IEA even though doing so does not maximize their utility. It follows that the number of participating countries will equal the number of type 1 countries (z). Thus, the larger the number of type 1 countries (which depends on norm strength and issue area), the larger the number of countries participating in the IEA. However, regardless of whether the number of type 1 countries is large or small, all participating countries will comply with the IEA, so there will be no noncompliance, despite the fact that the IEA enforces neither participation nor compliance. The 1954 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil (OILPOL) provides an example of an IEA lacking appropriate provisions for effective 7 enforcement of either participation or compliance. Indeed, in line with our theory, participation in OILPOL was rather limited. The agreement entered into force in 1958, upon being signed by 11 countries. By 1978, the number of signatories had reached 58. By then, however, a successor IEA which enforced both participation and compliance had been negotiated.11 OILPOL attempted to reduce oil dumping by means of setting performance standards. However, compliance with the standards was practically unenforceable (Barrett 2003, Mitchell 1994a, b).12 Although OILPOL’s Article VI states that penalties may be imposed for any unlawful discharges from a ship, noncompliance was difficult to detect, and even if breaches could be verified by coastal states, only flag states could prosecute. The latter, in turn, had little incentive to do so (Mitchell 1994b). There was noncompliance with OILPOL’s discharge standards. However, as Mitchell comments (1994a: 19), noncompliance is only to be expected in the initial phases of deep IEAs. Moreover, he argues that this noncompliance was due primarily to the lack of transparency which characterized the performance standards regime (Mitchell 1994a, b). The shift from performance standards to equipment standards in OILPOL’s successor MARPOL increased transparency, and also compliance rates.13 Second, consider an IEA that enforces compliance, but not participation (option 2). Assume that the threatened punishment for noncompliance is credible and sufficiently severe to outweigh the short-term benefit that a participating country can obtain by being noncompliant.14 Given this assumption, the IEA’s enforcement system will deter any participating type 2 countries from noncompliance. Because type 1 countries will always be compliant, it follows that all participating countries will be compliant in option 2 IEAs also. However, because there is no punishment for non-participation, the utility-maximizing option is non-participation. Accordingly, no type 2 countries will participate in the IEA, whereas all type 1 countries will participate and comply. The problems with an IEA that enforces compliance but not participation are: (1) that a country can contribute nothing to the public 11 The successor treaty, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78), entered into force in 1983. Compliance with MARPOL 73/78 has been virtually full, and the treaty currently has 145 signatories. See Barrett (2003) for a discussion of how MARPOL 73/78 succeeded in enforcing both participation and compliance. 12 The exact sizes of punishments were not specified, however, and it was not until the amendment adopted in 1962 that the treaty specified that penalties should be “adequate in severity to discourage any such unlawful discharge”. 13 However, as Downs et al. (1996) point out, the improved compliance performance may also be explained by the parallel introduction of potent compliance (and participation) enforcement. 14 Unless this assumption is fulfilled, the enforcement system will not change the incentives for type 2 countries and hence the IEA will be better categorized under option 1 than under option 2. 8 good and yet escape punishment by not participating, and (2) that a noncompliant participating country can escape punishment by withdrawing. Provided that at least some type 2 countries exist, these weaknesses will reduce the IEA’s effectiveness. The Kyoto Protocol provides an example of an IEA that aims to enforce compliance but not participation. Consistent with our theory, participation in Kyoto is far from full. While many countries have ratified Kyoto, only 37 countries have emissions limitation targets, and for countries such as Russia and Ukraine the targets are not effective (the hot air problem). Furthermore, Kyoto’s compliance enforcement system has received severe criticism. One of many objections is that a noncompliant member country can indeed escape punishment by withdrawing (Barrett 2003:385); withdrawal is possible because Kyoto does not enforce participation. Considering the weaknesses of Kyoto’s enforcement system, this IEA might be more correctly categorized under option 1 than under option 2. However, because Kyoto’s first commitment period expires only in December 2012, it remains to be seen whether all participating countries will comply.15 Third, consider an IEA that enforces participation, but not compliance (option 3). Assume that the threatened punishment for non-participation is credible and sufficiently severe to outweigh the incentive for non-participation. This means that a country will obtain less utility by not participating than by participating. Thus, all N countries (both type 1 countries and type 2 countries) will participate. However, because no punishment exists for noncompliance, the utility-maximizing option is to participate without complying. Hence, all type 2 countries will do so. Accordingly, type 1 countries will participate and comply, whereas type 2 countries will participate but not comply. The Montreal Protocol’s first enforcement system provides an example of an attempt to enforce participation but not compliance. This system allowed member countries to impose restrictions on trade with non-members in substances that threaten the ozone layer. Anecdotal evidence suggests that, consistent with our theory, this enforcement system induced some countries to participate. There is “direct evidence from some countries that the trade provisions were important in persuading them to accede to the treaty; a good example is the 15 Some Annex I countries are currently way off their emission target, and at least one (Canada) shows limited motivation to reach compliance. In April 2008 Greece was suspended from emissions trading under the Kyoto Protocol for failing to maintain a proper national system for recording GHG emissions, and consequently might face large fines in the European Court of Justice. 9 Republic of Korea, which initially expanded its domestic CFC production, but realizing the disadvantages of being shut out of Western markets, became a party” (Brack 2003: 220). Finally, consider an IEA that enforces both compliance and participation. Furthermore, assume: (1) that the threatened punishment for non-participation is credible and sufficiently severe to outweigh the incentive for nonparticipation, and (2) that the threatened punishment for noncompliance is also credible and sufficiently severe to outweigh the incentive for noncompliance by participating countries. The utility-maximizing course of action will then be to participate and comply. Thus, all N countries (both type 1 and type 2 countries) will participate. Moreover, all N countries will also comply. The Montreal Protocol’s current (second) compliance system provides an example of an attempt to enforce both compliance and participation. Montreal is widely regarded as highly successful. While several reasons exist for this success, Montreal’s enforcement system might partly explain it. While the first compliance system enforced only participation, provisions for enforcing compliance were soon added.16 Again, anecdotal evidence suggests that Montreal’s compliance enforcement system has induced some members to fulfill their commitments. Several examples exist of cases where the use of measures from the indicative list of consequences has been threatened against noncompliant members: “Their use has been threatened, in a series of MOP decisions, usually in the following terms: ‘These measures may include the possibility of actions available under Article 4, such as ensuring that the supply of CFCs … is ceased and that exporting parties [parties exporting to the noncomplying party] are not contributing to a continuing situation of non-compliance’. So far, this provision has never had to be used, but, as with the former non-parties that decided to accede, its existence appears to be important in encouraging compliance” (Brack 2003: 220).17 Table 1 summarizes these point predictions for the number of participating countries and the number of compliant countries for each of the four options. 16 For examples of cases of noncompliance with the Montreal Protocol, see http://ozone.unep.org/Publications/MP_Handbook/Section_2_Decisions/Article_8/decs-non-compliance/ . 17 This is analogous to the equilibrium for option 4 IEAs analyzed in section 4. In this equilibrium, enforcement measures are never actually used, precisely because their existence induces all countries to participate and comply. 10 Table 1:Number of participating and compliant countries in a deep18 IEA, depending on its enforcement system Enforcing Compliance? Enforcing No No Yes Option 1 Option 2 P=C=z P=C=z Option 3 Option 4 P = N, C = z P = N, C = N Participation? Yes Key: P = No. of participating countries; C = No. of compliant countries; z = No. of type 1 countries; N = Total no. of countries. Directional Predictions Providing accurate point predictions requires that all relevant factors (economic, political, institutional, demographic, technological, normative, cultural, and psychological) be fully incorporated into the model. Because it is virtually impossible to include all such factors in a theoretical model, point predictions will generally be biased.19 However, provided that this bias is roughly constant, we may still use point predictions to provide correct directional predictions. Consequently, empirical predictions of political science models are typically about relative differences and comparative statics (Fiorina 1996:88). Several interesting directional predictions can be derived from the entries in Table 1. First, circumstances exist under which all participating countries will comply regardless of whether the IEA enforces compliance. In an IEA that does not enforce participation (options 1 and 2) compliance enforcement will have no impact. With or without compliance enforcement, type 1 countries will participate and comply, while type 2 countries will not participate. This result 18 In shallow IEAs, our theory predicts that P = N, C = N, regardless of whether participation and/or compliance is enforced. 19 For example, the point prediction that all participating countries will comply in IEAs that belong in options 1, 2, and 4 will almost certainly overrate the actual number of compliant countries in most IEAs. 11 is in keeping with the managerial school’s claim that designing and incorporating coercive measures in treaties is largely “a waste of time” (Chayes & Chayes 1995:2). However, and second, circumstances also exist under which some participating countries will comply only if compliance is enforced. In IEAs that enforce participation (options 3 and 4), all countries will participate. But without enforcement of compliance (option 3), only the z type 1 countries will comply; the N – z type 2 countries will not comply. In contrast, with compliance enforcement (option 4), all N countries will comply. Thus, our theory predicts that enforcing compliance will increase the number of participating countries that comply, but only provided that the IEA also enforces participation. This result is in keeping with the enforcement school because it shows that enforcement can enhance compliance. Third, some countries will participate only if the IEA enforces participation, meaning that enforcing participation will cause the number of participating countries to increase.20 This is true regardless of whether the IEA enforces compliance, provided that the number of type 2 countries is bigger than zero (N – z > 0). If the IEA does not enforce participation (options 1 and 2), only the z type 1 countries participate. In contrast, if the IEA does enforce participation (options 3 and 4), all N countries will participate. This result may be said to be in keeping with the spirit of the enforcement school, although both schools have so far mostly focused on compliance. Fourth, circumstances exist under which enforcing participation will cause the number of noncompliant countries to increase. Consider an IEA that does not enforce compliance (options 1 and 3). If this IEA also does not enforce participation (option 1), only type 1 countries will participate, and all participating countries will comply. In contrast, if the IEA does enforce participation (option 3), all N countries will participate, but only type 1 countries will comply; type 2 countries will not. This prediction has also been overlooked by both schools. Finally, an IEA that enforces both compliance and participation (option 4) will achieve higher compliance or higher participation, or both, than any of the other three options. In an IEA that does not enforce participation (options 1 and 2) type 2 countries will not participate. In an IEA that enforces participation, but not compliance (option 3) type 2 countries will participate 20 It is worth noticing the asymmetry between the effect of compliance enforcement (on compliance) and the effect of participation enforcement (on participation). Compliance enforcement induces more countries to comply only provided that the IEA also enforces participation. In contrast, participation enforcement induces more countries to participate regardless of whether the IEA also enforces compliance. 12 but will not comply. Only in an IEA that enforces both compliance and participation (option 4) will both types of countries participate and comply. This is another prediction overlooked by both schools. Explaining Henkin’s Dictum Both schools acknowledge the validity of Henkin’s dictum.21 However, they explain differently why countries comply. While the managerial school emphasizes factors such as norms and administrative routines, the enforcement school attributes high compliance rates to the shallowness of many IEAs. Our theory suggests a third and novel explanation for Henkin’s dictum. As shown in table 1, all participating countries will comply with IEAs that do not enforce participation (options 1 and 2) because type 2 countries do not participate in such IEAs; so, all countries participating in such IEAs will be type 1 countries − which comply regardless of whether compliance is enforced. As mentioned, this result is in keeping with the managerial school. Moreover, however, our theory predicts that high compliance rates may also be caused by effective enforcement of both compliance and participation (option 4). In effect, in keeping with the enforcement school and contrary to the managerial school’s view, our theory suggests that for some IEAs, high compliance rates are caused (partly) by enforcement. Contrary to the enforcement school’s view, our theory suggests that we should expect high compliance rates even for deep IEAs without enforcement. Although we consider only deep IEAs, our theory predicts considerable rates of noncompliance only in IEAs that enforce participation but not compliance (option 3). As far as we know, very few such IEAs exist (the Montreal Protocol’s early phase is an exception). Our theory suggests that it is no coincidence that there are few such IEAs. Because enforcing participation but not compliance basically adds type 2 countries to the set of participating countries, the need for enforcing compliance will be greater in an option 3 IEA than in an option 1 IEA. Hence, the parties in an option 3 IEA will have an incentive to add effective compliance enforcement to the IEA’s institutional structure. If they were to do so (apparently this happened in the Montreal Protocol case) they Not all scholars subscribe to this view. For example, Keohane (1995: 217) notes that “compliance is not very adequate. I believe that every study that has looked hard at compliance has concluded…that compliance is spotty.” 21 13 would essentially switch from an option 3 to an option 4 IEA and noncompliance by type 2 countries would disappear. 4. A Formal Model of Enforcement, Participation, and Compliance We now present and analyze a simple formal model that enables us to consider in detail conditions under which countries will participate in and comply with an IEA aiming to provide a global public good.22 Existing formal models in this field typically consider either decisions about participation (while assuming that compliance is determined exogenously) or decisions about compliance (while assuming that participation is determined exogenously). By contrast, in the model presented and analyzed here, both compliance and participation are determined endogenously. Our model is novel because it extends the well-known N-player indefinitely repeated prisoners’ dilemma (NRPD) model23 in two significant ways. First, whereas the NRPD model assumes that each country has only two options in the stage game (‘Cooperate’ or ‘Defect’), we assume that each country has three options in the stage game: ‘Participate and Comply’ (P/C); ‘Participate and Not Comply’ (P/NC); or ‘Not Participate’ (NP). We assume that a country playing P/C in a particular period participates in the IEA and fully honors its commitment in that period. Playing P/C entails a fixed contribution to providing the public good at cost c. Similarly, a country playing P/NC participates in the IEA, but only partially honors its commitment.24 This entails a contribution that equals d (0 < d < 1) times the contribution entailed by choosing P/C, at cost dc (> 0). Finally, a country playing NP does not participate; therefore, it does not contribute. Hence, for such a country c = 0. 22 The game-theoretic literature on IEAs consists of two main strands. One uses repeated games to study the conditions under which participating countries will comply (e.g., Asheim & Holtsmark 2009; Barrett 1999, 2003; Finus and Rundshagen 1998). The other strand uses one-shot games to study the conditions under which countries will participate, assuming that participating countries always comply and that coalitions must be ‘stable’ in the sense that: (1) no member benefits by leaving the coalition and (2) no non-member benefits by joining it (e.g., Botteon and Carraro 1998, Carraro & Siniscalco 1993, Osmani and Tol 2006). Stable coalitions are typically (very) small. 23 See Barrett (1999a). 24 As Barrett (2005) reminds us, “the greatest harm that a signatory can inflict upon its fellow signatories is to increase its emissions to the level that would be individually rational for this country were it to withdraw from the treaty entirely. Further increases may be feasible, but they would also be self-damaging – and, hence, irrational. Smaller deviations may also be tried – that is, deviations of non-compliance rather than nonparticipation – but these can be deterred by smaller punishments” (italics added). 14 Including NP as an option in the stage game is consistent with the fact that most IEAs allow member countries to withdraw at any time, provided they give notice. Hence, deciding whether to participate cannot plausibly be seen as a one-off decision. However, one should not expect countries to move frequently in or out of IEAs. Including a possibility for moving in or out of the IEA is certainly not equivalent to saying that countries will frequently use this possibility. Indeed, our model suggests that countries will enter or withdraw from an IEA only because of exogenous institutional changes. Nevertheless, including NP as an option in the stage game has non-trivial implications. Second, whereas the NRPD model assumes that all countries are motivated by self-interest, we assume that there are two types of countries. Type 1countries participate in and comply with the IEA regardless of whether doing so is in their self-interest. We thus assume throughout that all type 1 countries adhere to strategy T1:25 T1: Play P/C in every period regardless of the game’s history. In contrast, type 2 countries participate in and comply with the IEA only when doing so maximizes their payoff. As in section 3, z is the number of type 1 countries, so that N - z is the number of type 2 countries. Notice that type 1 countries’ actions are not contingent on whether type 2 countries participate and comply. Therefore, type 1 countries do not punish type 2 countries that play NP or P/NC. 26 In our model it is simply impossible to always play P/C and yet punish other countries for norms-violating behavior. Hence, we assume that only type 2 countries enforce compliance and participation. Let k be the number of type 2 countries choosing P/C and let w be the number of type 2 countries choosing P/NC. The periodic payoff obtained by a type 2 country playing P/C is: U ( P / C ) b( z k ) bdw c 25 Technically, we assume that for type 1 countries T1 is dominant in the repeated game. Because we model enforcement by means of reciprocity (the punishment consists of reduced abatement in the event of non-participation and/or noncompliance), we assume that type 1 countries abstain from imposing the punishment. After all, type 1 countries’ choice to participate in, and comply with, an IEA seeking to abate GHG emissions is assumed to be motivated by a norm prescribing such abatement. If enforcement were instead modeled by means of e.g. sanctions, the assumption that type 1 countries abstain from imposing the punishment would seem less relevant. 26 15 Similarly, the payoff obtained by a type 2 country playing P/NC is: U ( P / NC ) b( z k ) bdw dc Finally, the payoff obtained by a type 2 country playing NP is: U ( NP) b( z k ) bdw We assume that c ≥ 2b, and that b( N z ) c . These assumptions entail (1) that N – z > 2, meaning that there are at least three type 2 countries, and (2) that a situation in which all countries participate and comply Pareto-dominates a situation in which only type 1 countries participate and comply.27 Type 2 countries discount future payoffs using a common discount factor . As in section 3, we consider four options: Option 1 is an IEA that enforces neither compliance nor participation. Option 2 is an IEA that enforces compliance, but not participation. Option 3 is an IEA that enforces participation but not compliance. Finally, option 4 is an IEA that enforces both compliance and participation. We now show that an equilibrium entailing full participation and full compliance is possible only in an IEA that enforces both compliance and participation (option 4). Option 1: Enforcing neither Compliance nor Participation First, consider the possibility of an equilibrium in which all type 2 countries use a strategy such as T1, which (1) prescribes P/C in every period and (2) provides no punishment for deviating by playing P/NC or for deviating by playing NP. Because NP strictly dominates both P/C and P/NC in the stage game, a type 2 country j will obtain a strictly higher sum of discounted payoffs if it deviates by playing NP in every period than if it does not deviate. Thus, a strategy that provides no punishment either for playing P/NC or for playing NP cannot sustain full participation and full compliance as a Nash equilibrium. 27 This is true regardless of whether type 2 countries play NP or P/NC in the latter situation. 16 Option 2: Enforcing Compliance but Not Participation Next, consider the possibility of an equilibrium in which all type 2 countries use a strategy that provides punishment for deviating by playing P/NC, but not for deviating by playing NP. Such a strategy enforces compliance but not participation. The trigger strategy T2 is an example: T2: Play P/C as long as no country plays P/NC. If at some stage at least one country plays P/NC, play NP indefinitely. We have shown (see Option 1) that without punishment for playing NP, country j will obtain a strictly higher sum of discounted payoffs if it deviates by playing NP in every period than if it does not deviate. Therefore, a strategy that provides punishment for deviating by playing P/NC, but no punishment for deviating by playing NP, cannot sustain full participation and full compliance as a Nash equilibrium. Option 3: Enforcing Participation but Not Compliance Now consider the possibility of an equilibrium in which all type 2 countries use a strategy that provides punishment for deviating by playing NP, but not for deviating by playing P/NC. Such a strategy enforces participation but not compliance. The trigger strategy T3 is an example: T3: Play P/C as long as no country plays NP. If at some stage at least one country plays NP, play NP in all subsequent periods. Because P/NC strictly dominates P/C in the stage game, and because there is no punishment for deviating by playing P/NC, a type 2 country will obtain a strictly higher sum of discounted payoffs if it deviates by playing P/NC in every period than if it does not deviate. Accordingly, a strategy that provides punishment for deviating by playing NP, but not for deviating by playing P/NC, cannot sustain full participation and full compliance as a Nash equilibrium. Option 4: Enforcing both Compliance and Participation 17 Finally, consider the possibility of an equilibrium in which all type 2 countries use a strategy that provides punishment both for deviating by playing P/NC and for deviating by playing NP. Such a strategy enforces both compliance and participation. The trigger strategy T4 is an example: T4: Play P/C as long as all countries play P/C. If at some stage at least one country deviates by playing either P/NC or NP, play NP in all subsequent periods. Let S be the strategy profile in which all type 1 countries adhere to T1 and all type 2 countries adhere to T4. Barrett and Stavins (2003) argue that if a strategy is able to deter nonparticipation, then it will also deter noncompliance. This is clearly true for a strategy such as T4, which provides the same punishment for noncompliance as for non-participation.28 Hence, to identify the conditions under which S is a Nash equilibrium, we need only consider the conditions under which T4 deters type 2 countries from deviating by playing NP in some period. As long as all type 1 countries stick to T1, and all type 2 countries stick to T4, type 2 country j will obtain a periodic payoff of bN c , so its sum of discounted payoffs will be (bN c) /(1 ) . If country j deviates in period t by playing NP, it obtains b( N 1) in this period. From period t+1 onwards, type 1 countries will continue to play P/C, whereas type 2 countries will play NP, meaning that country j obtains (at best) bz in period t+1 and in each subsequent period. The sum of discounted payoffs country j obtains if it deviates is therefore b( N 1) bz /(1 ) . It is individually rational to stick to T4 unless country j obtains a strictly higher sum of discounted payoffs by deviating. This condition is fulfilled if (bN c) /(1 ) b( N 1) bz /(1 ) . Solving for gives: (1) c b b( N z 1) Condition 1 says that T4 is a best response for country j given that other type 2 countries stick to T4 and provided that future payoffs are not discounted too heavily. When this condition holds, S is a Nash equilibrium. Because T4 is a best response not only along the equilibrium path, but also after deviation from this path (playing NP is a best response when other type 2 28 However, it is not true for a strategy such as T3, which punishes participation but not noncompliance. 18 countries play NP), S is also a subgame-perfect equilibrium.29 In this equilibrium both type 1 and type 2 countries participate and comply in every period. Notice that (for given N) the right-hand side of condition 1 increases when c or z increases, and decreases when b increases. For given N and , country j is more likely to stick to T4: (1) when the compliance cost (c) for a participating country is small; (2) when the marginal gain from cooperation (b) is large, so that country j’s own contribution makes a noticeable difference to the provision of the public good; and (3) when the number of type 2 countries (N - z) is large, so that the punishment threatened by T4 is severe. Interestingly, this suggests that an increase in the number of type 1 countries (a larger z) will make the remaining type 2 countries less inclined to participate in and comply with the IEA. 5. Three Limitations and a Policy Implication In this section we briefly consider three limitations of our theory and offer a simple policy recommendation. First, although our theory resolves several points of disagreement between the managerial and enforcement schools, at least one issue remains that our theory does not address. The enforcement school will likely argue that z (the number of type 1 countries) is typically close to zero, while the managerial school will likely argue that z is typically close to N. Whereas our theory is agnostic on this issue, it acknowledges that the number of type 1 countries may vary across issue areas and over time. Moreover, it entails that there is a role to play for enforcement as long as z < N, and that enforcement will be more important the closer z is to zero. Second, while our theory argues that full participation and full compliance can be achieved only by enforcing both compliance and participation, it acknowledges that speaking softly might also play a role in securing compliance. In particular, in IEAs that do not enforce participation, enforcement of compliance will have no effect, so facilitation will clearly be the superior approach. However, because our theory simply assumes the presence of norms, it does not explore the conditions under which norms will have a bearing on compliance or the 29 This subgame-perfect equilibrium is not weakly renegotiation-proof (in the sense of Farrell and Maskin 1989). However, it has recently been shown that in an N-player repeated game with discounting, outcomes that can be sustained as a subgame-perfect equilibrium can also be sustained as a weakly renegotiation-proof equilibrium for sufficiently high δ (Asheim and Holtsmark 2009). For a similar result for 2-player repeated games, see Van Damme (1989). 19 conditions under which countries might involuntarily fail to comply.30 The theory does suggest that facilitation is more likely to work for certain countries (type 1 countries) and for certain IEAs (options 1 and 2) than for others, but is otherwise silent on when the managerial approach will be effective. Moreover, our theory assumes that countries belong to either type 1 or 2, treating membership as given for a given IEA. An interesting task for further research concerns relaxing this assumption, incorporating the possibility that whether the logic of appropriateness or the logic of consequentiality ultimately more strongly motivates behavior may change over the IEA’s history. Third, our model considers only enforcement that provides credible and sufficiently severe punishment for non-participation or noncompliance, or both. Such enforcement will often be infeasible, for two reasons: (1) Systems for enforcing participation infringe on sovereignty by providing sticks against non-participating countries without their consent. Participating countries might be reluctant to contribute to such infringements on sovereignty as a matter of principle; (2) Systems for enforcing compliance must usually be adopted through consensus among the participating countries, and participating countries that expect compliance to be difficult, costly, or incompatible with other policy goals may not consent to a system that makes noncompliance even more costly than compliance. Hence, while our theory helps us understand when enforcement enhances compliance and participation, it does not address the crucial question of when enforcement will be feasible. Finally, we offer a simple policy recommendation. While our theory is agnostic as to whether the number of type 1 countries is large or small, it is a basic premise of this theory that the international system contains both type 1 and type 2 countries in at least some issue areas. While facilitation will suffice for type 1 countries, enforcement is required to induce type 2 countries to participate and comply. Thus, our theory recommends that IEAs include provisions for facilitation as well as provisions for enforcement of both compliance and participation. 6. Conclusions The managerial school is right that countries are unlikely to voluntarily participate in IEAs and then deliberately cheat. Yet the enforcement school is right that deep IEAs will 30 See Finnemore & Sikkink (2005) for an excellent analysis of the conditions under which norms will be influential in world politics. 20 nevertheless require enforcement. The explanation for this apparent contradiction is that only type 1 countries will voluntarily participate. In contrast, type 2 countries will not participate unless participation is enforced. And if induced to participate, type 2 countries will fail to comply unless compliance is enforced. Hence, while some countries will participate in and comply with IEAs even without enforcement, achieving full compliance and full participation requires that both compliance and participation be enforced. References Asheim, G.B. & B. Holtsmark (2009). “Renegotiation Proof Climate Agreements ― Conditions for Pareto-efficiency”, Environmental and Resource Economics (in press). Available at: http://www.springerlink.com/content/100263/?Content+Status=Accepted&sort=p_OnlineDate &sortorder=desc&v=condensed&o=10 Axelrod, R. and R. O. Keohane (1986). “Achieving Cooperation Under Anarchy: Strategies and Institutions”, pp. 226–54 in K. A. Oye (ed) Cooperation Under Anarchy, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Barrett, S. (1999). “A Theory of Full International Cooperation”, Journal of Theoretical Politics 11 (4): 519–541. Barrett, S. (2003). Environment and Statecraft: The Strategy of Environmental TreatyMaking, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Barrett, S. (2005). “The Theory of International Environmental Agreements”, pp. 1457–1516 in K.G Mäler and J.R. Vincent (eds.) Handbook of Environmental Economics, vol. 3. Barrett, S. and R. Stavins (2003). “Increasing Participation and Compliance in International Climate Change Agreements”, International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 3: 349–376. Botteon M. and C. Carraro (1998). “Strategies for environmental negotiations: Issue Linkage with Heterogeneous Countries”, in N. Hanley and H. Folmer (eds), Game Theory and the Environment. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA. Brack, D. (2003). “Monitoring the Montreal Protocol”, in T. Findlay (ed.), Verification Handbook 2003. http://www.vertic.org/assets/YB03/VY03_Brack.pdf Breitmeier, H., O.R. Young and M. Zürn (2007). Analyzing International Environmental Regimes: From Case Study to Data Base. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Brown Weiss, E. and H.K. Jacobson, eds. (1998). Engaging Countries: Strengthening Compliance with International Environmental Accords. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 21 Carraro C. and D. Siniscalco D (1993). Strategies for the international protection of the environment, Journal of Public Economics, 52(3): 309–328. Chayes, A. and A. H. Chayes. (1993). “On Compliance”, International Organization 47:175– 205. Chayes, A. and A.H. Chayes (1995). The New Sovereignty, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Chayes, A., A.H. Chayes and R.B Mitchell (1998). “Managing Compliance. A Comparative Perspective”, pp. 39–62 in E. Brown Weiss and H.K. Jacobson (eds), Engaging Countries: Strengthening Compliance with International Environmental Accords. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Checkel, J. (2001). “Why Comply? Social Learning and European Identity Change”, International Organization 55 (3): 553–588. Downs, G. W., D. M. Rocke, and P. N.Barsoom (1996). “Is the Good News about Compliance Good News about Cooperation?” International Organization 50, 379–406. Elster, J. (1989a). The Cement of Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Elster, J. (1989b). Nuts and Bolts for the Social Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Farrell, J. and E. Maskin (1989). “Renegotiation in Repeated Games, Games and Economic Behavior 1: 327–60. Finus M., and B. Rundshagen B (1998) “Toward a Positive Theory of Coalition Formation and Endogenous Instrument Choice in Global Pollution Control”, Public Choice 96 (1–2): 145–186. Fiorina, M. (1996). “Rational Choice, Empirical Contributions, and the Scientific Enterprise”, pp. 85–94 in J. Friedman (ed.), The Rational Choice Controversy. New Haven: Yale University Press. Mitchell, R.B. (1994a). Intentional Oil Pollution at Sea: Environmental Policy and Treaty Compliance, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press. Mitchell, R.B. (1994b). Regime Design Matters: Intentional Oil Pollution and Treaty Compliance, International Organization, 48(3): 425–458. Mitchell, R.B. (2005). “Flexibility, Compliance and Norm Development in the Climate Regime”, in O.S. Stokke, J. Hovi and G. Ulfstein (eds.), Implementing the Climate Regime. International Compliance. London: Earthscan. Osmani, D. and R.S.J. Tol (2007) Toward farsightedly stable international environmental agreements: part one. Hamburg University Working Papers, FNU-140. Oye, K. (1985). Explaining Cooperation under Anarchy: Hypotheses and Strategies, World Politics 38 (1): 1–24. Raustiala, K. and A.M. Slaughter (2002). “International Law, International Relations, And Compliance”, in W. Caerlsnaes, T. Risse, and B.A. Simmons, Handbook of International Relations. London: Sage. Raustiala, K. and D.G. Victor (1998). “Conclusions”, pp. 659–707 in D.G. Victor, K. Raustiala, and E.B. Skolnikioff (eds), The Implementation and Effectiveness of International Environmental Commitments: Theory and Evidence, Mass., MIT Press. 22 Tallberg, J. (2002). Paths to Compliance: Enforcement, Management and the European Union, International Organization 56 (3): 609–643 Underdal, A. (1998). Explaining Compliance and Defection: Three Models, European Journal of International Relations 4 (1): 5–30. Van Damme, E. (1989), “Renegotiation-proof Equilibria in Repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma”, Journal of Economic Theory 47: 206–217. Victor, D. G. (1998). “The Operation and Effectiveness of the Montreal Protocol’s NonCompliance Procedure”, pp. 137–76 in D.G. Victor, K. Raustiala and E.B. Skolnikoff (eds.) The Implementation and Effectiveness of International Environmental Commitments:Theory and Evidence, Mass., MIT Press. 23