D7.1 Business Start-Ups Youth Self-Employment Policy

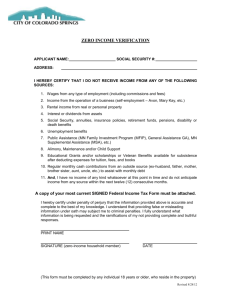

advertisement