What the Emperor knew New Evidence about Hirohito`s role in Pearl

advertisement

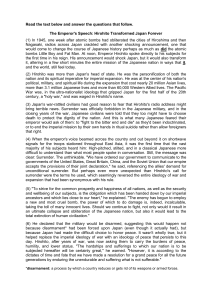

What the Emperor knew New Evidence about Hirohito’s role in Pearl Harbor attack At noon on Aug. 15, 1945, millions of people across war-charred Japan turned their radios on and listened tensely to a voice they had never heard before. Crackly and high-pitched, it spoke an antique, learned language barely comprehensible to ordinary Japanese. “The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage,” the voice reported, “while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest.” The voice was that of Emperor Hirohito, a man deemed so divine that doctors examined him with silk gloves. The Emperor couldn’t bring himself to utter the words “defeat” or “surrender,” but his message remained clear: He was declaring an end to World War II. Hirohito’s surrender broadcast inspired one of history’s great, and most sensitive, “what if” questions: If the Emperor had the power to end the war, how much responsibility did he share for starting it? For four decades, the official Japanese line has been that Hirohito – who died in 1989 at the age of 87 – knew little of what went on and, under Japan’s Constitution, lacked the authority to do anything about it. Now comes evidence that only half of that script is true. According to a previously undiscovered memoir, Hirohito knew plenty. In an oral history recorded in writing by an aide shortly after the surrender and published in the magazine Bunget Shunju this month, Hirohito acknowledged that he was aware in 1941 that Japan’s political leaders were planning to attack the United States. America’s oil embargo, the Emperor said, had “cornered” Japan. “Once the situation had come to this point, it was natural that advocacy for going to war became predominant. If, at that time, I suppressed opinions in favor of war, public opinion would have certainly surged, with people asking why Japan should surrender so easily when it had a highly efficient Army and Navy, well trained over the years. It would have led to a coup d’etat” that likely would have cost him his life. “That would have been fine,” the Emperor added, but still “a very violent war would have developed” and “Japan could have perished.” As revealing as Hirohito’s memoirs may be, however, they are not likely to significantly expand the debate over his World War II role because, in Japan, there is hardly any debate to expand. Open discussion of the sensitive subject remains politically taboo in a nation that has yet to come to grips with its past. Last January, a right-wing fanatic shot Nagasaki Mayor Hitoshi Motoshima after the politician suggested that Hirohito “shares responsibility for the war, as well as all of us who lived in that period.” The mayor survived, but the gunman’s message was obvious to other would-be detractors. Even without the threat of violence, most Japanese would prefer simply not to think about their tarnished past or the Emperor’s wartime role. In this, they are aided by the government, which, unlike that of Germany, is widely accused of glossing over its nation’s activities in the war. A month ago, conservative politician Shintaro Ishihara claimed in a Playboy magazine interview that Japan’s 1937 massacre of more than 100,000 Chinese in Nanking never took place – a comment that prompted howls of protest in other Asian countries but only unpleasant memories in Japan. ______________________________________________________________________________ This article, written by Jim Impoco, originally appeared in U.S. News & World Report on November 26, 1990. ______________________________________________________________________________ A recent survey of high school graduates in Japan indicated that fewer than half had been taught anything about World War II. Textbooks that deal with the war generally use vague terms. Two years ago, right-wing complaints forced one textbook publisher to withdraw a passage that told of Japanese soldiers bayoneting babies in Malaysia. Substituted for it was a story based on “My Fair Lady.” The magazine that disclosed Hirohito’s memoir reached readers just as the nation was enthroning his son, Emperor Akihito. The timing raised hackles in parts of the government and in the imperial palace. But nothing changes the fact that, in Japan, World War II is still a closed book. Even more so now that a new Emperor, untainted by the past, has ascended the Chrysanthemum Throne.