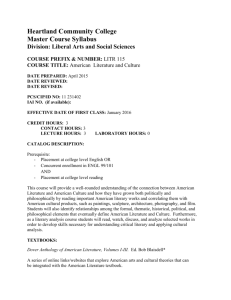

Spring 2014 Undergraduate Course Descriptions AML 3031

advertisement

Spring 2014 Undergraduate Course Descriptions AML 3031-10784: Periods of Early American Literature Keith Cartwright This course will consist of readings in American literature from the pre-colonial period to the Civil War, with particular attention devoted to two distinct periods. We will consider the ways in which such periods as "the colonial" or the "American Renaissance" are constructed. AML 3041-10653: Periods of Later American Literature LIT 4934-12580: Literature and the Empathic Imagination (Seminar) Tru Leverette We can look to literature superficially for entertainment or more deeply for its ability to illuminate life and provide us with windows into diverse experiences. In exposing ourselves to other ways of being in the world, we can spark our empathic imagination, increasing our awareness of and emotional response to realities far different from our own. Our reading in this class will explore American fiction that we will (hopefully) enjoy, but we will look to texts that allow us to explore the question "How will we be?" Our texts will help us delve empathically into others' experiences in order that we question how people in various contexts choose to structure their lives; what is privileged; and what values—both conscious and unconscious—are used to shape lives, relationships, and communities. By extension, our exploration will allow self-reflection on how we want to go about forming our own lives, relationships, and communities. AML 3102-12535: American Fiction Bart Welling Was D. H. Lawrence right to claim that “[t]he essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, a killer”? Is our country a melting pot, a mosaic, a salad bowl, a quilt, a giant poem, an empire, a “land that has never been yet” (Hughes), or something else? How influential has “the American dream” really been in shaping our lives and literature? Can one story drive an entire nation to war? Conversely, can the stories we tell about who we are, and where we are, help us live more justly and sustainably on the planet? We will grapple with questions like these on a regular basis as we attempt to make sense both of American places and American stories. America has always been a fertile place for fiction; as many scholars have observed, “America” itself was a powerful fiction long before the establishment of the United States, when only a tiny fraction of the lands of the western hemisphere had been claimed and mapped by Europeans. In this class we will explore key schools and developments in the fiction of the United States in the context of some of the larger cultural narratives that have inspired, shaped, and often bedeviled our identities, values, and lifeways as inhabitants of a bewilderingly diverse “New World.” Our goal will not simply be to use literature to deconstruct these master narratives (America as Promised Land, the United States as America, Americans as Rugged Individualists, the U.S. as Bastion of Freedom, and so on). That would be too easy. Rather, we will carefully track the complex interplay between master narratives and historical realities, and between foundational group narratives and the individual literary productions of some of our most talented writers of fiction. We will also frequently turn back to scrutinize the contemporary American “storyscape,” asking how our private life stories mesh with new master narratives, how cultural fictions that have been officially disavowed (such as mythologies of white supremacy) continue to haunt us, how old narratives have adapted to new social trends and technologies of expression, and how the most useful and beautiful American fictions may be passed on to future generations. AML 3621-11323: Black American Literature – Race and Genre Tru Leverette Black American Literature: Race & Genre Literary categories have long been nationalized, and the literature of minority groups within nations has been sub-categorized based on authors’ minority status. We might question why and on what basis categories such as black American literature exist. Likewise, we might ask whether such categories should exist at all. Are there distinct literary characteristics, specific tropes or certain styles and aesthetics, that can be said to distinguish black American literature from other American literatures? Is the distinction solely racial? This course will explore these and other questions through the study of texts, from slave narratives to contemporary novels, written by African-American writers. We will also read literary criticism that questions the genre of African-American literature within an increasingly globalized literary marketplace. AML 4242-12536: Place, Race, and Gender in Modern U.S. Environmental Writing and Ecocriticism (20th Century American Literature) Bart Welling Who cares about environmental writing? In an era of catastrophic oil spills, collapsing ocean ecosystems, mass terrestrial extinctions, global climate change, worsening water shortages, evergrowing mountains of garbage and toxic waste, and ongoing problems with deforestation, desertification, and out-of-control wildfires—all compounded by the fact that the world’s human population is projected to keep expanding well into this century—it would make more sense to ask, Who can afford not to read environmental writing? Far from merely celebrating rocks and trees, authors who focus on questions about our place in the biosphere and our relationships with nonhuman beings can challenge our most deeply help assumptions about who we are and how we live. Moreover, they can help us envision a future defined not by scarcity and conflict but by greater abundance for all of the world’s species and cultures. The literary tradition that Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854) helped usher in has played a major role in the creation of national parks and the preservation of wilderness areas, but it has also participated in key debates on issues that affect the lives of people in the heart of the city: sprawl and overpopulation, smog and nuclear radiation, pesticides and organic farming, homelessness and urban planning. Environmental writers will continue to light our way as we move towards greener sources of energy, wiser systems of transportation, and cultures centering on sustainability and compassion rather than hyper-consumption and techno-narcissism. In short, if you’re interested in writing that has the potential to spark profound transformations in how people think, work, eat, shop, build, get around, and even express themselves spiritually, then you should care about environmental writing. Despite the unfortunate fact that environmental issues tend to be coded as liberal concerns in contemporary U. S. culture, this class is not designed to “convert” students to any one political perspective. But it does aim to introduce students to a set of environmentally-oriented texts and new ways of reading them—critical practices that have proliferated in recent years under the sign of ecocriticism—that will involve everyone in non-partisan political activities of the best kind: engaging in spirited dialogue with the authors on our list and each other; analyzing and producing environmental and ecocritical rhetoric; getting our hands dirty as we leave the classroom to test and build arguments about the everyday places we inhabit, and asking deep questions about how they might be transformed. The class will also engage with the politics of ethnic, cultural, gender, sexual, and even human identity as we explore points of convergence between environmental and ecocritical issues and the topics that have dominated critical debates in literary studies since the 1960s. We will focus, in particular, on the dialectic between experiences of place in the modern U. S. and our standpoints as readers and writers who belong to diverse cultures, ethnicities, genders, socioeconomic classes, and other groups—but who also dwell in a country marked by unique and powerful master narratives about nature and our nation’s place in it. CLT 4110-12538: Classical Backgrounds of Western Literature Samuel Kimball In this course we will read some of the major Greek works, along with one Roman epic, that are part of the classical inheritance of Western literature. We will do so in order to understand how this literary heritage has influenced the emergence and subsequent transformation of Western consciousness in general and Western religious thought in particular. To this end we will focus on how Greek literature and Virgil’s Aeneid represent the pagan Olympian gods, above all Zeus, compared with how selected books of the Bible (Genesis, the Gospels, and Revelation) develop a monotheistic conception of a single Godhead who, in the New Testament, sacrifices his only begotten son. Our itinerary will begin with Hesiod’s Theogony, which depicts the origin and history of the Olympian gods, and contrast this narrative with how Genesis envisions the creation and history of the world, with how the Gospel of John reinterprets the Genesis account of God’s inaugural manifestation, and with how Revelation anticipates an apocalyptic end to the history that begins with Genesis. We will then turn to Homer’s Odyssey, which we will read in relation to René Girard’s signature work of anthropological and cultural criticism, Violence and the Sacred, which traces the origin of human sociality to the discovery or invention of sacrificial victimage and its institutionalization in ritual and its subsequent commemoration in epic narratives and tragic drama. In tandem with this interpretive task, we will read various Greek tragedies—Sophocles’ Oedipus the King, Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound, and Euripides’ The Bacchae—in relation to the Eucharist and the Crucifixion in order to suggest how Jesus offers a critique of the Greek gods and the sacrificial worship they demanded. We will then extend our comparison by returning to Aeschylus (specifically, the three dramas that make up his Oresteia) and to Euripides (his Medea). We will conclude our investigation of the religious concerns that are central to early Western literature by critically examining how Virgil envisions the founding of the Roman Empire in his epic poem, the Aeneid. As we proceed, we will endeavor to understand what it means to think critically about the sacred. What is involved in this activity? How does one go about such critical thinking? How do Greek and Roman literary texts themselves offer critical perspectives on their pagan tradition? What has Judeo-Christianity inherited from these texts, how and why has it revised this inheritance, and to what extent has this revision been a form of cultural critique? What is the relation between the sacred and the symbolic order, including the ideological conditioning and social control of consciousness that the symbolic order enforces? As part of the theoretical framework for our discussions of these and other questions, we will read Penelope Deutscher’s short book, How to Read Derrida. This introduction to Derrida’s thought will provide a framework for examining to what extent Greek literature is able to deconstruct the “logocentric” economy of the Greek mind that produces Greek culture, especially as Greek culture makes the transition from orality to literacy. We will also read Derrick de Kerckhove’s essay, “Theory of Greek Tragedy,” which examines how Greek drama participates in this momentous cultural transition. To this end we will endeavor to understand how Greek literature addresses the intellectual problems and especially the emotional challenges that arise for a polytheistic society that is learning how to adapt its thinking to the new technology of alphabetic writing, a development that, for reasons we shall explore, supports the rise of monotheism. CRW 2201-11269: Introduction to Creative Non-Fiction Mark Ari The National Foundation for the Arts defines creative nonfiction as “factual prose that is also literary – infused with the stylistic devices, tropes and rhetorical flourishes of the best fiction and the most lyrical of narrative poetry.” Creative Nonfiction may use scenes, dialogue, and cinematic and sensory detail to increase vividness of writing. But, in the words of Philip Lopate, it can also be “reflective writing where thinking and the play of consciousness is the main actor.” In this class, we explore possibilities that range from Gonzo to Tinker Creek, and everything between and beyond. The course further provides an introduction to basic creative writing concepts and methods in the service of a radically subjective narrative or lyrical approach to the factual. Experimentation is encouraged. Laughter is relished. CRW 2930-12542: Horror Fiction Workshop Will Ludwigsen H.P. Lovecraft once wrote, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” It may well be that the very first stories our hominid ancestors ever told were as simple as jumping from the caves shouting, “Boo!” Horror is our way of inoculating ourselves against the real horrors of the world, making them small and concrete and portable in our hands. By the end of this course, you will understand the basic principles of writing horror fiction in the short form, including: voice, character, plot, point of view, scene, description, and revision; specific topics important to horror fiction writers including horror tropes and the different subgenres of the form; and special issues of working with or against the long history and active culture of genre fiction. CRW 2930-12541: Makings of Memory – Writings of Remembrance and Oblivion Clark Lunberry What does memory have to tell us, to reveal to us, about the world, about ourselves? In this class, we will read, view and discuss a variety of different types of memory-related materials, all of them united in their focus upon remembrance and imagination, the shaping of a life as it is seen through re-collection, as if through the rear-view mirror. The assigned readings for this class will be intended as starting-off points for your careful reflection, our wide-ranging discussions and, then, your own engaged writing, always moving us towards a more fruitful examination of our own memories and imagination. How are memories made, and to what end? What does it, as Wittgenstein said, “feel like to remember”? How are memories written, filmed and photographed (and, in the process, perhaps fabricated), and for what purpose? What is the role of memory (and forgetful oblivion) in the creation, and sustaining, of identity? And what happens to that identity, that sense of self, when memories falter or fail, as we recognize that which “memory cannot contain,” as we, as Shakespeare counseled, “Commit to these waste blanks”? CRW 3110-11271: Fiction Workshop Mark Ari Each of us, however long we’ve been writing, are wherever we are and hoping to get “better,” whatever this means to anyone at a particular time. We are always, every one of us, “beginners.” In this workshop, we write lies. Perhaps we do so in the service of some greater truth. I don’t know. You’ll have to tell me and try to convince me. We tackle technical concerns and seek methods by which the reliable resources of imagination can be tapped in the service of narrative fabrication. We read and write fiction. We talk and write about the fiction written by others. We bite nails and open veins and tend to the work at hand. Experimentation is encouraged. Laughter is relished. CRW 3930-11939: New Media Writing Mark Ari What is creative writing in a post-paper world? What new inspiration might we find in its freedoms and constraints? With these questions in mind, we will examine the exciting possibilities suggested by new methods of communication and the genre-busting potential of new technologies. As writers, our focus will be on tapping the reliable sources of imagination to discover opportunities for new strategies and forms of fiction and/or creative nonfiction. Students may, if they chose, incorporate other genres (poetry, songwriting, drama) and forms (film making, visual art, music, sound, design, etc.) This is not a course in creating content for websites. It is one that explores how we can find inspiration and artful expression in a new era of real-time creation, publication, and interaction. Collaboration is possible. Experimentation is encouraged. Laughter is relished. CRW 4924-11932: Ghostwriting Mark Ari Prerequisite: Permission of the Instructor (email - mari@unf.edu). This class will focus on the art of writing someone else’s story. Students will learn interviewing techniques and prepare transcriptions of recorded interviews. They will review the raw material gathered, deriving and shaping story to create drafts that will be revised and polished into finished manuscript. Exercises and mini-projects will be used to learn and practice for the main work of the class which will focus on a single subject, an individual from our community who has lived a unique and varied life. Our manuscripts will tell this person’s story. Since all of the elements of successful storytelling will be addressed (point of view, characterization, voice, etc.), this course is especially useful to students who write creative nonfiction and fiction, those seeking careers in editing, publishing, or ghostwriting, and those who simply want to tell the stories of interesting people. ENC 2451-11329: Medicine in Narrative and the News Chris Gabbard Per capita, Americans spend far more on health care than do the people of any of the other advanced industrialized nations. Health-care spending at the current rate is not sustainable. And yet, the results are disappointing: in terms of health outcomes (life expectancy, infant mortality, recovery from curable diseases, etc.), the U.S. ranks down in the pack. U.S. health-care delivery systems are undergoing major change. The Affordable Health Care Act, a.k.a. Obamacare, has gone into effect. While these mandates represent major reform, they constitute only a part of the transformation. This course will explore some of the big issues and pressing problems in how medical care is delivered in the U.S. It also will examine how medical care operates in other advanced nations. Students will read about the issues, write summaries, refresh themselves on the basics of grammar and mechanics, and engage in a substantial research project (investigating a topic of their choosing) using APA method. ENC 2460: Writing for Business Brenda Maxey-Billings This course introduces students to rhetorical components of business writing and to strategies for successful research-based writing in diverse academic and non-academic situations within business. This course familiarizes students with expectations for business documents, including formatting, content, and style. Students practice writing in a variety of genres, including the argumentative essay, and address a variety of audiences, using research strategies relevant to business and related professional communities. The class focuses on four cornerstones of effective professional communication: (1) Surface correctness; (2) “Plain English” style; (3) Logical, Appropriate, and Ethical Content; and (4) Document Format and Design. ENC 3250 (online): Professional Communication - Business Brenda Maxey-Billings In this distance-learning class, students work toward improving the quality and content of their professional writing and familiarizing themselves with various document formats. Thus, the class focuses on four cornerstones of effective professional communication: (1) Surface correctness; (2) “Plain English” style; (3) Logical, Appropriate, and Ethical Content; and (4) Document Format and Design. The coursework requires students to investigate rhetorical and visual features of communication; research and formulate strong documents; master “Plain English” stylistic skills; demonstrate comprehension of written instructions; improve their writing’s grammatical, mechanical, and syntactical correctness; and gain practice in the conventions of professional writing. During the term, each student produces several professionally formatted documents/texts (correspondence, employment materials, technical writing, case studies, etc.), and one formal online “presentation” to the class. ENC 3250-11845: Professional Communication Tim Donovan When you begin a profession many of you will spend a great deal of your time writing--nearly 40%. Yet until recently you have had little, if any, experience in the kind of writing required for a technical or business profession. Your writing assignments generally have been research projects, literary essays, or short lab reports directed to an audience that is more knowledgeable about the subject matter: your professor. Professional Communication is an intermediate course that prepares students for the types of written communication found in professional settings. Rather than mere information transfer, professional communication generally translates and mediates highly complex details efficiently for a colleague, supervisor, client, or a less expert audience. Likewise, the professional reports you will be writing on the job will address more complex audiences and have more instrumental purposes; unlike your professor, these audiences are dependent on the precision and clarity of your written work. Thus, the importance of this course is finding the ways of making this communication effective and meaningful to these varied audiences. ENC 3310-10173: Writing Prose James Beasley ENC 3310 is described as "writing of various kinds, such as speculation, reports, documented articles or criticism, with emphasis on persuasion as the object." The purpose of this class is to first of all demonstrate how that object of persuasion is culturally constructed in American academic institutions in the 21st century. The second purpose of this course is to demonstrate the kind of thinking that writing in an American academic institution allows writers to do, and conversely, to demonstrate the kinds of thinking that writing in an American academic institution in the 21st century does not allow writers to do. To this end, we will focus on the modern nature of this writing, the overtly masculine nature of this writing, and the American nature of this kind of writing. By taking this class, you will become critically conscious of the artifice and constructed-ness of writing in American academic institutions in the 21st century, which after many years of uninterrupted and unexamined practice, may have become opaque or invisible to you. ENC 3930-12559: The Essay James Beasley This course will examine the history and philosophical journey of the essay form. The French word for essay is not a noun, but a verb—to essai, to experiment, to try. Students will examine the essay's beginnings in the age of exploration, its mid-twentieth century maturation, and its postmodern reinvigoration. Students will not only analyze the beginnings of these movements but also examine contemporary essayists whose experimental natures embody the essay's exploratory nature. ENC 4930-11943: Research Methods in English James Beasley ENC 4930, Research Methods in English, is designed to introduce final-year undergraduate students to the various methods of research methodologies available to them by examining examples of archival methodology, case study research, and by examining discourse analysis testing. The purpose of this introduction is to help prepare students for graduate school research, to prepare for teacher-generated action research, and to aid humanities students in being more thoughtful consumers of research reports and papers. ENC 4930-12560: Literary Theory Nicholas de Villiers This course introduces students to a set of key critical terms and approaches in literary theory and interpretation—author, reading, subjectivity, culture, ideology, history, space/time, postmodernism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, gender, race, class, sexuality—using Nealon and Giroux’s The Theory Toolbox: Critical Concepts for the New Humanities as our guide, along with a few literary theory essays. Students will learn how to use these terms and approaches through classroom discussion, close reading, and critical writing about different literary forms including a novel (Manuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman), a published diary, and a few short stories. ENG 4013-10174 & 10175: Approaches to Literary Interpretation Alex Menocal ENG 4013 introduces students to an array of critical concepts and interpretative approaches that should help students improve their abilities to read literature critically. Throughout the semester, in lectures, discussions, and close readings of four novels, we’ll explore some “familiar” literary concepts and questions. For example, how does the author develop characters (i.e., characterization)? What important motifs or patterns structure the narrative? What is the narrative’s point of view, and how is it significant? In addition to these concepts and questions, though, we’ll explore some “unfamiliar” concepts and approaches. For example, how is the author of a text always already dead? How are we subjects of language or of ideology? How is identity or desire produced through imitation? Academics often characterize these sorts of questions as “theoretical” because they formulate some general principles about a subject: language, narratives, authors, identity, subjectivity, desire, and where texts begin and end, to name a few. We will examine some of these theoretical statements over the semester as time permits. ENL 3333-10176: Shakespeare John Chapman This course will examine eight of Shakespeare’s plays in literary, historical, and artistic contexts. Students will explore early modern thought, poetry, and drama. In addition, the course will examine how Shakespeare’s work has had profound influence on our conception of what a human being is, of human psychology, and of human relationships. Indeed, many of his plays almost presciently address social issues that still dominate the modern cultural landscape. Studying Shakespeare in this light will increase the intellectual maturation and clarification of our own values through examination of ideas and attitudes in literary/cultural contexts and especially through articulation of these notions in academic discourse. Response papers and exams will help students develop skills in verbal analysis, critical thinking, and detection of subtlety through reading, discussion, and writing about these great works. The readings in this course will cover two comedies (Much Ado About Nothing, Measure For Measure), two histories (The Tragedy of King Richard III, The Life of King Henry the Fifth), two tragedies (Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Othello, the Moor of Venice), and one romance (The Tempest). ENL 3501-10177: Periods of Early British Literature (“The Restoration in Film”) Chris Gabbard In English cultural history, the Restoration (1660-1689) was a wild and licentious time, one the English spent the next two-hundred-and-fifty years trying to forget. The era’s reputation explains why it has been a favorite cinematic subject. With a critical eye we will screen four films set in the period: The Libertine (2004; Johnny Depp, Samantha Morton, and John Malcovich), Stage Beauty (2004; Billy Crudup, Claire Danes, Rupert Everett), The Last King (2003-4; Rufus Sewell, Robert Graves, Diana Rigg), and Restoration (1995; Robert Downey Jr., Sam Neill, Meg Ryan, Ian McKellen). We will screen these films in conjunction with reading Samson Agonistes by John Milton, Absalom and Achitophel by John Dryden, and various poems by John Wilmot (Earl of Rochester). We also will read three plays (William Wycheley’s The Country Wife, George Etherege’s The Man of Mode, Aphra Behn’s The Rover) and fiction from the period. Students will take midterm and final exams and daily reading quizzes, and they will participate in producing group websites. The class will require no major papers. ENL 3503-10654: Periods of Later British Literature Alex Menocal This course will survey some of the major literary works produced in England between 1789 and 1918, works representing the Romantic Period, the Victorian Period, the fin de siècle, and Modernism. Over the semester we’ll set out (1) to specify the conventions of the works that have come to be linked with a particular period and (2) to examine how these works engage with some of the social, cultural, and political issues of their time: for example, the French Revolution, the Poor Laws, industrialization and urbanization, the professionalization of knowledge and society, the rise of the middle class, education, the moralization of work, Darwinism and degeneration fears, World War I and nationalism, Empire and colonialism, and others. Students will read some poetry, a few short stories, and two novels. ENL 3503-10654 (online): Periods of Later British Literature Marnie Jones We will read classic literature from the Victorian, Modern, and Post-Modern periods, focusing on how each period portrayed the quest for self-understanding in response to rapid cultural and historic changes: time changes everything—or does it? We will consider each period’s characteristic features, while also examining the relations between them, attending to what the UNF course catalog describes as the “aesthetic, linguistic, and cultural changes by which periods are constructed.” Students will read Dickens’ Great Expectations, Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, Conrad’s The Secret Sharer, Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Eliot’s Four Quartets, and Barnes’ Sense of an Ending. In an anonymous survey at mid-term Fall 2013, all respondents said 1] the course was well structured; 2] the mini video lectures put the literature in cultural context; 3] they learned as much as they would in a traditional class. They also encouraged me to tell you it is challenging: that the only way to succeed in an online class is to be disciplined. Grades are based upon weekly discussion posts, a journal, weekly quizzes, and three exams. ENL 4230-12561 (online): Restoration/18th Century Literature (“Spectacles of Physical Deviance”) Chris Gabbard The course’s readings both respond to and facilitate the transition from a religious to a scientific mindset unfolding in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. To better understand this transition, the course will focus on bodies in literary texts, specifically, those that are monstrous, deformed, or defective. Such bodies increasing were coming to be seen less as demon possessed or signs of God's wrath and more as indicators of scientific pathology—as accidents of nature. Rosemarie Garland Thomson describes this period as witnessing "a movement from a narrative of the marvelous to a narrative of the deviant," one in which "wonder becomes error." Primary readings include William Shakespeare's Richard the Third, John Milton's Samson Agonistes, Aphra Behn's "The Dumb Virgin" and “The Blind Lady a Beauty," Jonathan Swift's Gulliver’s Travels, Sarah Scott's Millenium Hall [sic], William Hay's Deformity: An Essay, and other texts. Students will take midterm and final exams, participate in weekly online discussions, and write two short papers. FIL 2000-11024, 11026: Film Appreciation Jason Mauro This course will focus on examining exactly what kind of strange and contested space the film screen is. By alternating between formalist and film texts, we will open up our eyes to how various film practitioners and critics regard the seemingly unproblematic phenomenon of a white rectangle. Is the film screen a frame, a window, mirror or a filter? Does this white plane hold within it other geometries, like white light holds within it all other colors? Are there hidden resources within this seemingly simple surface that we ignore at our peril? The purpose of this course is to introduce you the basic terms and questions of film analysis, and to prepare you for more advanced courses in film studies. FIL 3006-12564: Analyzing Films Nicholas de Villiers This course introduces students to key terms for interpreting film, including important concepts and trends in the field of cinema studies. Students will learn how to watch films with a critical eye, how to discuss cinematic form and meaning, and how to write coherent and persuasive essays analyzing film. This course provides an important foundation for more specialized courses in the film studies minor, but will benefit anyone who wants to better understand how movies affect us, and how to put that experience into words. FIL 3828-12565: International Film Jillian Smith Don’t leave college without exposing yourself to the beautifully strange and profound experience of foreign cinema: it transports you not only to different worlds, but different time, space, and being. It becomes a part of who you are forever. In this course we will watch some of the most watched films in the history of international cinema by focusing on national film movements, movements that have been recognized for their influence on the development of cinema world wide—American Romantic Realism, German Expressionism, Soviet Montage, French New Wave, and more. In the process we will learn film vocabulary, film style, film technique, and some film theory. We will also read about historical context to get a sense of the politics of film. Students will be expected to read essays, write reflections on the films, and engage in other exercises to improve film comprehension and analysis. Satisfies the survey requirement for film minors. Satisfies awesome educational experience for non-film minors. THERE ARE NO PREREQUISITES—anyone having difficulty registering should contact Dr. Jillian Smith, jlsmith@unf.edu FIL 3300-11646: Documentary Studies FIL 4932-11647: Advanced Documentary Studies Jillian Smith The art of documentary is in to capturing and giving form to the narratives that circulate around us every day. In this course we will be practicing this art through the technique of the interview, which will provide the heart of the films we make. We will also learn styles and techniques of documentary film in order to move beyond traditional documentary and into creative documentary. By the end of the course students will have made a digital documentary film by learning how to interview, shoot video, record audio, and edit a short documentary using Final Cut software. Students who are interested in filmmaking of any kind will find this course to be invaluable, and students who are primarily interested in watching film will find that their film viewing skills are strengthened considerably. Students who have already taken the course are welcomed, as are newcomers. Be prepared for a fluctuating workload and for logging some hours outside of class to shoot and then edit your documentary. THERE ARE NO PREREQUISITES ‐ anyone having difficulty registering please contact Dr. Jillian Smith, jlsmith@unf.edu . LIN 3930-12566: Sociolinguistics Jeanette Berger The goal of this course is an introduction to sociolinguistic theory. We will examine issues of power and solidarity through the relationships between language and gender, race, class, and ethnicity. These relationships will focus on the different subcategories of sociolinguistics and the sociology of language and on the social varieties of English spoken today. Sociolinguistics encompasses a wide variety of approaches to the study of language. This course sets aside the Chomskyan construct of an ideal speaker-hearer in a homogeneous speech community in order to examine real speakers in real speech communities. Course requirements include a weekly sociolinguistic journal, article presentation, fieldwork project, midterm and final exam. This course requires a significant amount of reading—both foundational and contemporary texts in sociolinguistics. LIT 3213-10932, 11950: The Art of Critical Reading Tim Donovan Our task in this course is to learn the techniques necessary to read and write critically. All of us know how to read and write. We have been doing it since primary school or earlier. This course however will stretch and strengthen that readied strength. Readers often say, “I loved that book!” But what do they mean? What analysis underlies this enthusiasm? That is our task. Therefore, we will be reading with pleasure (or not), reading critically and reading with sophistication. We’ve all learned basic reading skills, but just as any technician does, we must repeat and refine our background and skill. Literary interpretation is not merely a technical art limited to literature. Rather, it is a foundation for sophisticated critical thinking within history, philosophy, culture, politics, media, arts, and even sciences. For we not only “read” poems, but also films, advertisements, textbooks, equations, timelines, faces, weather, traffic, emotions, intentions. More than anything, our art requires basic tools whose use we will continue to refine (for example, character, point of view, paradox). Think of the class as a beginning carpentry class where we will learn how to use tools functionally and then artistically. Everyone thinks s/he can use a hammer, until his or her thumb and fingers are painfully swollen. Often, we misuse hammers because we don’t understand the difference between hammers, and the technique to propel the heft and force of the tool. This is similarly the case with literary tools. Everyone thinks they understand and use simple concepts of character, plot and more while reading. But more often than not this understanding is rudimentary or simplified. To test your understanding of literary tools we will also be writing a lot. Once, we learn which hammer to choose, its heft, its force, the best swing, then, we will be able to build something artful with strategy, skill, and substance. Our art in this class will manifest in written interpretations of fiction. Critical Reading is also, perhaps primarily, a writing class. And in the weeks that we have together we will be focusing on our writing intensively. We will read, and re-read. And we will write, and re-write. By the end of the course you will have the critical facility with many literary techniques. You should be able to identify, define, and use these techniques and tools for the problem-solving art of literary interpretation. You will be expected to craft well composed, analytical interpretations that put these tools and techniques to work. You will be expected to write organized essays, driven by analytical methods, that use controlled sentences and college-level diction and that demonstrate conceptual coherence. What’s more, your ability to interpret literature will further train you to interpret film, culture, politics, and the media. LIT 3213-11951: The Art of Critical Reading Marnie Jones “The best stories invoke wonder.” So says Andrew Stanton, writer of the Toy Story movies, director of WALL-E & Finding Nemo, in his Ted Talk. By the end of this course you will have a better understanding of the power of reading, how stories evoke wonder, and how literary and non-literary texts work. Dickens’ Bleak House incorporates all of life and several literary genres, as it weaves an amazingly intricate plot. We will analyze the pleasures it provides; we will study the sophisticated literary techniques that drive story, making us care about characters and issues while offering truth about the human experience. In an anonymous survey at mid-term Fall 2013, all but one of the students expressed surprise at how much they were enjoying the reading. Representative comments include “glad we are reading it” to “appreciating it” to the most frequent response: “loving it.” [Examples of the latter: “I absolutely love it”; “I have grown to love it”; “I “love it, especially as it gains momentum.”] All the students spoke of having a feeling of “accomplishment”; all said that class discussion was both extremely helpful and enjoyable. Grades are based upon the application of literary terms in discussion, quizzes, exams, and a presentation that results in a Final Paper. Text: Norton Critical Edition, Bleak House (required). LIT 3213-12568: The Art of Critical Reading Jillian Smith Literary interpretation is an art. And it is a foundation for sophisticated critical thinking and writing within the contexts of history, philosophy, culture, politics, media, arts, and even sciences. Yet, this sophisticated thinking is grounded in basic techniques. This course is dedicated to teaching students to define, identify, and apply basic literary tools and techniques. Metaphor, paradox, setting, point of view, symbol—these techniques that we tend to identify and use loosely, we will learn to use with precision and purpose. The goal of the class is to teach you how to read literature, and thus any text, with intensity. You will leave with knowledge of literary terms and techniques and the ability to write clearly and analytically about them. By the end of the course you should have mastery of the foundational components of a critical essay. English majors should run to this course, creative writers often find it invaluable, and all majors are welcome. (This course, because of its coverage of narrative technique and textual analysis, fulfills a requirement for film minors.) LIT 3331-10953 (online): Children’s Literature Mary Baron In this course we will read classic and contemporary literature considered suitable for elementary and middle school students, as well as literary criticism, developmental psychology, and pedagogical theory. As we move through the course we will ask the following questions, among many others: What do we mean by childhood? What is its history? What are the functions of childhood in our culture? How does childhood happen in other cultures? What are the tasks of childhood? How is childhood different for females and males? What characteristics place a text within the field of "children’s literature"? What are some characteristic themes and concerns of the texts? What are the major sub-genres in the field? Does children’s literature serve one or more social functions? What ethical issues do teachers, librarians, and others face? As a result of this course, students should be able to: Understand the significant features of literary media and genres, evaluate evidence to support an insightful interpretation of a text or tale, understand the social and political impact of literatures, write clear, critical, creative, convincing reports that analyze primary and/or secondary sources, make an informative presentation or report, supporting their position with appropriate literary and scholarly evidence. LIT 3333-10180: Adolescent Literature Sandra McDonald LIT 3930-12570: Inventing Death Jason Mauro We begin with and form this class around Ernest Becker’s landmark book, The Denial of Death. The claim he makes is difficult in every possible way: in response to our mortality (the fact to which we are both horrifyingly sensitive and yet profoundly numb) we create the culture(s) we have. This class is dedicated to exploring the implications, the applications and the extent of that claim. In order to do so we will be reading through material that is intellectually and psychologically difficult. Our discussions will be devoted to how our texts critique what we regard as normalcy, and will therefore likely tread on some of our most reflexive or cherished assumptions and beliefs. I would wish for this gathering a supportive, encouraging and sensitive environment within which this critique can emerge. LIT 4650-12571: Comparative Literature Keith Cartwright We will be reading First Coast writing. This will include writing from our own north Florida "First Coast" region as well as writing from other historic "contact zones" across the South, and the Americas, with a couple of readings even reaching across the Atlantic to Africa. Most of what we read from these first coasts of cross-cultural experience and imagination will be 20th and 21st century texts (writers like Toni Morrison, James Weldon Johnson, Patrick Chamoiseau, Zora Neale Hurston, Lydia Cabrera, Eudora Welty, Joy Harjo, and a number of contemporary New Orleans poets. But we will also be reading a few folk narratives and selections from a series of travel narratives (from North Florida) that offer samplings of cross-cultural encounter across the centuries (from Bartram to Cabeza de Vaca). We will explore the depths and challenges of intensely cross-cultural writing from spaces (like our own) of deep crosscultural experience. Samplings of music and film will be integral to this course's holistic approach as we seek to move beyond the First Coast's gated communities--and across certain disciplinary and conceptual gulfs. LIT 4930-12573: Fairy Tales Now and Then Mary Baron Not all Fairy Tales have happy endings. Many classic European tales depict curses, murder, rape, and cannibalism; later retellings often continue and even extend these topics. Some scholars believe the tales speak about the deepest fears of human beings; abandonment, loss, and death, in order to prepare us for the inevitable. We will read classic, contemporary, and post-modern tales which circle around these topics. We will study their contexts, their cultures, and their narrative structures in an attempt to discern their utility in the past and today. Students will take a very active role in course design and class discussion. Evaluation will include blackboard postings, a student-written midterm, and a final paper/project. The ability to write evidence-based persuasive papers is essential to success in the course. LIT 4930-12574: Dirty Souths – Sex & Satan, Blues & BBQ Keith Cartwright This is a course dedicated to study of the music and literature of the Dirty South--from the early twentieth century to the present. The full title is “Dirty Souths - Sex & Satan, Blues & BBQ.” Each class will begin with focus upon a musical recording from the US South, paired with an assigned reading from southern literature. We will be discussing the licit and the illicit in postplantation spaces, the sacred and the profane, southern spaces as zombifying surveillance states and as musicating (and often culinary) sites of soulful suppleness and reanimation. Texts will include work by Jean Toomer, James Weldon Johnson, Lillian Smith, Stetson Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Natasha Trethewey, Joy Harjo, Andrew Hudgins, and more, as well as samplings of movies such as The Help, Beasts of the Southern Wild, Mississippi Masala, and Mud. The course’s musical focus will draw from artists such as Louis Armstrong, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Hank Williams, Dizzy Gillespie, Elvis Presley, Ray Charles, Loretta Lynn, Sun Ra, James Brown, the Allman Brothers, Michael Jackson, the Dixie Chicks, Ludacris, Goodie Mob, Driveby Truckers, and the Carolina Chocolate Drops, among others. The arts from southern spaces--with their long history of apartheid and of spiritual division of sheep from goats--must be approached holistically, and sometimes even against the grain of what our institutions have accredited or approved. We will launch these discussions, respectfully with each other, but in holistic readings that seek to move beyond or under or through the gated communities that surround us. LIT 4930-12575: Literature/Survival Bart Welling Zombies. Meteor impacts. Cannibal death cults. Bioengineered global mega-plagues. Nuclear apocalypse, alien attacks, cyborg revolutions, terminal power blackouts, out-of-control nanites, catastrophic drought and famine, howling subzero super-storms, and homicidal genetically engineered animals running amok. If you’ve watched any popular movies lately or read any bestselling books published since World War II, you’ve probably encountered all of these end-of-the-world scenarios and more. Surely no culture in history has spent as much time as ours imagining and, perhaps, anticipating its own demise (along with the collapse of human civilization in general). By the same token, no culture has had so much knowledge and power and, simultaneously, so little political will to combat such plausible game-ending threats as global warming, the depletion of the world’s oil reserves, and a major flu pandemic that, according to public health experts, is overdue by several decades. What’s going on? Why are we so invested in speculating about, and maybe even celebrating, our own impending doom? (When I wrote these words, the Hollywood zombie thriller World War Z had grossed over half a billion dollars globally, and books in the evangelical Left Behind series had sold enough copies to fill over sixty institutions the size of Carpenter Library). At the same time, why are most of us apparently so uninterested in having an honest national dialogue about preventing, or at least preparing for, the disasters that are most likely on the horizon? Does the recent explosion of post-apocalyptic narratives in American popular culture represent a) a means of bracing ourselves for what we suspect will be a much less comfortable life in the future, b) widespread longing for a “reboot” of modern human culture, c) a mass purgation of long-repressed guilt for what we have done to the planet and to other cultures, d) the last gasps of a terminally ill society that can no longer find pleasure in anything but dehumanizing spectacles of chaos and carnage, trashed ecosystems, and sexual victimization, e) something else, or f) all of the above? In this class we will situate post-apocalyptic literature and film historically, analyzing the relationship between end-of-the-world narratives and some of the more frightening developments of the last few decades, from the birth of the atomic era to 9/11 to the melting of the Arctic. But our historical investigations will reach back far beyond the modern era as we study what scholars have been saying in the last few years about the evolutionary origins of narrative and what might be called the survival value of literature. How did stories help our ancestors negotiate the everyday challenges posed by large predators, unpredictable weather, disease, and hostile fellow humans? How does modern literature reflect this evolutionary background? How has narrative helped keep endangered cultures alive in real “post-apocalyptic” environments, such as indigenous lands in the Americas in the centuries after European conquest? How might certain contemporary post-apocalyptic narratives, instead of merely entertaining us, or paralyzing us, help us rethink some of our most dangerous apocalyptic attitudes and world-destroying behaviors? In what forms might literature itself survive in the future? While the books and films we will explore are of recent vintage, we will be participating in an ancient dialogue concerning some of the most basic and profound questions regarding human identity, community, and our rightful place in a dynamic and unpredictable “more-than-human” world. LIT 4930-12577: Being Bored - Literatures of Radical Boredom Clark Lunberry Boredom was invented in the 19th century (or so), and its creation continues to afflict and entertain us to this day. We have, of course, a love-hate relationship with boredom; or it (like a virus) has a relationship with us. We just can't seem to shake it, to find a cure for this curiously modern condition of being bored. Ever since its infectious spread, writers and artists have found boredom irresistibly interesting as a topic, as it crops up again and again in their works. So much so that one might wonder if boredom is a fundamental fact for being modern, a diagnosed symptom of our tiresome and tedious age: boredom, being bored, being bored with being; or even, as the 19th century playwright Henrik Ibsen wrote of Hedda Gabler, of her “one real talent in life … Boring [herself] to death.” Our focus in this class will be upon a variety of materials, from modern and contemporary fiction, theater, poetry, painting and performance, where boredom is often at the chilled heart of the matter presented, setting in motion events that threaten at any moment to collapse beneath their own exhausting weight. How has such boredom, such dis/ease, been represented in literature and the arts? Why did it arise and how has it endured as a representable theme? And finally, perhaps paradoxically, how can boredom, “radical boredom,” be such a rich, revealing and, yes, fascinating focus for writers, artists and readers alike? LIT 4934-12579: Gender, Sexuality, and Culture (Seminar) Nicholas de Villiers Why are the gendered body, sexual desire, and eroticism so heavily invested with significance—so meaning-laden—in our culture? Why are many women hesitant to call themselves “feminists”? What is the history of the symbiotic and mutually exclusive concepts of “homosexual” and “heterosexual”? Has “queer” culture become mainstream? This course creates a space where these much-contested issues can be approached in an atmosphere of free and open inquiry. We will examine the history of feminism’s “waves,” and the history of gay and lesbian studies, as well as what has been called the New Gender Politics concerned with transgender, transsexuality, and intersex. We will also consider the intersections between gender, sexuality, and other vectors of oppression such as class and race. We will read important works in feminist theory, gender studies, and queer theory, and consider how they can help us read works of literature, film, visual art, and popular culture. This senior seminar is designed as a capstone experience emphasizing undergraduate research, so students will develop, write, and workshop a short research paper drawing on the course themes and additional library research according to their areas of interest. LIT 4934-12581: Magic and Realism (Seminar) Jennifer Lieberman Realism is an influential movement in American literary history. It is also a concept readers invoke to describe the feeling of disbelief successfully suspended: how many times have you heard or uttered the compliment, “that story just felt so real”? Even fantastic narratives can elicit this feeling: they can transport readers into their own reality, or they can illuminate actualities that seem to confound “realistic” description. This course will investigate the ideal of realism by engaging with literary texts and with critical studies of the genre. We will discuss why realism emerged as a literary value, why readers continue to use words like “realistic” to judge literary merit, and why authors may deviate from the conventions of realism in order to communicate broader truths about human life. We will read works across the spectrum from mimetic realism through magical realism, including pieces by Stephen Crane, Jorge Luis Borges, Maxine Hong Kingston, Jonathan Safran Foer, and others. During the semester, students will construct creative and analytical projects that explore the potentials and limitations of realism as a literary mode. At the end of the semester, we will debate why magic has infiltrated American literary realism: do we need magical tropes to express certain “realities”? Or do magical narratives strive to communicate something else entirely? LIT 4991-12931: The Problem of Evil Mary Baron Readings primarily in literature, but also in psychology, sociology and theology, the course is an exploration of ideas about the origins and causes of evil. We will grapple with many serious questions: Is evil a universal concept, or is it culturally defined? How can we know if a person, place, or thing is evil? What is an appropriate response to evil? Who decides? Is God involved? THE 3111-12584: History of Drama II Alex Menocal This course will examine two important movements in modern drama: realism and avant-garde theater. Specifically, we’ll examine how these forms revolutionized the theatre. The realism of Ibsen and Strindberg, for example, sets out to replace melodramatic representations of character and plot with “naturalistic” or “realistic” portrayals of characters and actions that may take into account the psychological, biological, and social forces which determine human behavior. Avant-garde theater, however, will reject the attempts of realism to reproduce the illusion of reality—a slice-of-life--on the stage. First, we’ll trace the development of realism and naturalism in the theater from its inception in the works of the founders of Modernism (Ibsen, Chekhov, and Strindberg) through to its transformation in the works of American playwrights (Williams, Miller, and Hansberry). Finally, we’ll examine 20th century rejections of realist tenets in Brecht’s epic theater, Beckett’s Theater of the Absurd, and Pirandello’s meta-theater. THE 4524-12578: Theater for Social Change Pam Monteleone This course is a hands-on, participatory workshop that will introduce you to a collection of games, techniques, and exercises for using theater as a vehicle for social and personal change. You will be introduced to the techniques of Augusto Boal’s Forum Theatre, a revolutionary form of participatory theater that transforms real community concerns into invigorating theatrical dialogue. The class will create Forum performances that empower participants to collectively investigate thorny issues and rehearse problem-solving strategies to implement in the real world. No theater experience or training is necessary. You will be asked to bring with you a desire to play, learn, and grow in an intimate, highly personal setting. Dr. Pam Monteleone, pmontele@unf.edu, or 904-704-3207. THE 4923-10181: Production – Romeo and Juliet Pam Monteleone This course offers practical experience in the design and/or execution of a major department production. This semester the Department of English is producing Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Students will be involved in the practical exigencies of translating a script into a theatrical event. Students will engage in various aspects of theater production, including research, publicity and promotion, and/or set construction, lighting, sound, and costuming. Students will be expected to demonstrate professionalism as exhibited in communication, time-management, leadership, organizational and teamwork skills. This course is offered for variable credit and may be repeated for up twelve (12) credits. Department permission is required prior to registration. Dr. Pam Monteleone, pmontele@unf.edu, or 904-704-3207. TPP 4155-12968: Performance – Romeo and Juliet Pam Monteleone This course is for students interested in acting in a major department production. This semester the Department of English is producing Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The course focuses on preparing students for a role on stage. It includes script analysis, character development, and vocal and movement techniques associated with acting Shakespeare. Students will develop tools for exploring heightened language, speech structure and rhythm, scansion, and phrasing, not as ends in themselves but as a means to creating the physical, verbal, and emotional lives of complex characters. “Words are meant to delight, to disturb and to provoke,” says Cicely Berry, “not merely make sense.” Students will learn the rehearsal process and living in the moment as part of an ensemble. They will be expected to demonstrate professionalism and teamwork. A commitment to substantial rehearsal time is required. This course is offered for variable credit and may be repeated for up twelve (12) credits. Department permission is required prior to registration. Auditions will be held on Friday, January 17 and Saturday, January 18. Students interested in acting must attend auditions and be cast in a role. Dr. Pam Monteleone, pmontele@unf.edu, or 904-704-3207. TPP3103-11958: Acting II - Doing Shakespeare in the Schools and on the Stage Pam Monteleone Will you be asked to teach Romeo and Juliet? Julius Caesar? Macbeth? Do you feel prepared? Confident? Ready? This course is for prospective teachers, actors, and anyone who loves “doing” Shakespeare. The aim is to put students at ease with the language. We will focus on the vocal and physical techniques necessary to bring the characters and stories to life. Students will develop tools for exploring heightened language, speech structure and rhythm, scansion, and phrasing, not as ends in themselves but as a means to creating the physical, verbal, and emotional lives of complex characters. “Words are meant to delight, to disturb and to provoke,” says Cicely Berry, “not merely make sense.” Prerequisite: TPP 2100 or permission of instructor. Dr. Pam Monteleone, pmontele@unf.edu, or 904704-3207.