Cory Drexel ART 275 11-21-11 Research Paper Rough Draft

advertisement

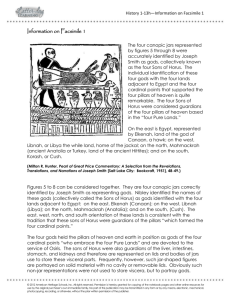

Cory Drexel 11-21-11 ART 275 Research Paper Rough Draft Ancient Egyptian art and architecture is renowned worldwide for its powerful symbolism. Having a wide array of Gods and myths dealing with the universal energy of all things concerning life, death and the afterlife the Egyptians believed strongly in the creation of art to tribute individuals who were passing over to the next phase of existence. The Egyptians also believed that at least one of their gods had a hand in the happenings of all aspects of life, death and the afterlife. The Pharaohs and Kings throughout Egyptian history were said to have descended from the Falcon God Horus himself, whose connection to other Egyptian Gods lead him to be personified as a heroic and protective deity. In life, Horus was said to give the Pharaoh his divine right to rule and in death, art created with Horus’s image protected and preserved the body of the deceased. In this paper, I will provide and describe examples of Ancient Egyptian art created for burial and mummification depicting the Eye of Horus as a positive reoccurring symbol affiliated with royalty, protection, rebirth and preservation. Many different animals play keys rolls in Egyptian beliefs involving spirituality and appear in numerous examples of art and architecture. The jackal for instance, represents the Egyptian god of mummification Anubis, one of the most important Gods associated with death and the afterlife. The scarab beetle symbolizing new life and creation is a representative of the solar God of resurrection Khepri. The falcon God Horus is almost always depicted as a falcon, most likely a peregrine falcon. If not a falcon his eye alone can be found in a multitude of examples of art. Although the eye has a number of functions and meanings they all fall within the same realms of connections to either that of royalty, protection or preservation. The image of the falcon itself, however, is a more usually assimilated with royalty than that of the eye. Horus’s powers of protection and preservation came to be linked to the Pharaoh in both life and death. In ancient Egyptian lore and mythology Horus entered a battle with the god Set, master of darkness, chaos and desert storms. Horus’s symbolism throughout Egyptian history gains a lot of its foundation from the events and results of this battle with the God Set. The conflict between Set and Horus has meanings that go beyond geographical boundaries; the heart of the conflict deals with the opposition of civilization and barbarism or that of law and brute force (Assmann pg.43). As the story goes, Set tore out the eye of Horus during their battle. Thus the God was even more so reliant on his naturally sharp sight. The battle resulted in Set losing one of his testicles and Horus temporarily losing his eye. After the battle the God Thoth restored Horus’s eye so that he could uphold the cosmic order of the sun God (Hornung and Bryan pg.124). From this restorative process it is said that Thoth was able to miraculously complete the part of Horus’s eye that had been destroyed. The newly regenerated organ came to be known as the Wedjat, which means “sound one” or “sound eye” (Hornung and Bryan pg.124). From there on the eye of Horus or the Wedjat became a symbol containing restoration and preservation powers and was used in art all throughout Egyptian history. Ancient Egyptians are known for their process of mummification on the bodies of the deceased in which various organs are removed, placed in separate containers and finally the body is wrapped to aid in its preservation. One part of the mummification process included an incision being made on the left flank of the body, through which the organs were eventually removed one by one. Once all of the necessary organs had been removed the wound would be sewn up and a plague would be placed over it. On a particular plague, which was placed over the incision made on King Psusennes I, was known as a Wedjat Eye Plague. On this plague the Eye of Horus or the Wedjat can be found smack dap in the center, with the four main gods who protect the deceased flanking the eye on either side (Hornung and Byran pg.124). Some of the major functions of mummification aimed at health and completeness, which the eye of Wedjat came to be synonymous with (Hornung and Byran pg.124). The eye itself was carefully placed so that it would be directly over the incision. On King Psusennes I’s plague the four gods who watch over the deceased are Horus’s four sons Kebehsenuef, Duamutef, Imsety and Hapy. In an alternative interpretation of the plagues imagery the four gods seem to be worshipping the eye as an equal of the sun God who has descended from the heavens to travel the underworld (Hornung and Byran pg.124). Each of the four sons can be found with a uraeus snake protruding from their headdress and since it is believed that these snakes protected the sun by spitting fire it is a possibility that their inclusion represents the providing of light to guide the sun God as he journeys through the darkness (Hornung and Byran pg.124). Other forms of art bearing the Wedjat have been discovered and linked to burials and mummification involving the preservation and new life of the deceased. A pharaoh by the name of Sheshonk II who ruled during the Twenty-Second Dynasty was discovered with two bracelets bearing the Wedjat on them around each of his wrists. Deciphering of the inscriptions on the bracelets tells us that they actually belonged to that of a previous ruler and founder of the Twenty-Second Dyansty, Sheshonk I (Hornung and Bryan pg.128). Elaborate in design the bracelets are composed of gold, glass and small stone pieces. Then central image of the bracelet depicts the Wedjat hovering over a basket, symbolizing and providing a hieroglyphic desire for “all health” (Hornung and Bryan pg.129). The overall health of the mummy, especially the bones, is invoked by the Wedjat and therein the preservation of the wrist bones and rest of the body is emphasized in the function of the bracelets (Hornung and Bryan pg.129). As with the previous example of the plague of King Psuennes, it is believed that the power of the sun God embodied on the bracelets Wedjats are also intended to guide the king through his journey to the netherworld (Hornung and Bryan pg.129). Along with burial jewelry the Egyptians put a major emphasis on the creation, decoration and overall function of all things associated with funerary devices and customs. Some of the most famous examples of ancient art and architecture of all time are those of the coffins of the deceased kings, the sarcophagi, and their eternal resting places, the pyramids. Decoration and function of burial devices went hand in hand when it came to the Egyptians. The Egyptians style of life was devoted largely in part to the journey to the next phase of existence, the afterlife. When creating and designing sarcophagi for a deceased individual the Egyptians would take all necessary measures to ensure that the body would not only have an eternal resting place but that the deceased’s spirit would have safe and complete passage to the afterlife. During the Middle Kingdom in particular, the mummified individual would be placed on their left side with their head and neck on a headrest on which protective formulas would be written (Dunand and Lichtenberg pg.29). On the exterior of the coffin, especially for those of the wealthy, friezes of objects symbolizing the offerings and other goods which belonged to the deceased would be carved or painted alongside that of hieroglyphic texts (Dunand and Lichtenberg pg.29). Although these middle kingdom coffins could be found with individualized friezes on their exterior, there was a unifying factor that could be found on the left side of most of them; the Eye of Horus. The two eyes of the Wedjat would be painted on the exterior of the left side of the coffin so that the deceased individual would be “looking” through them (Dunand and Lichtenberg pg.29). The Wedjat were intended to be in front of the deceased’s face, so that they in turn could magically “see” and “exit” through the gate which the eyes created (Dunand and Lichtenberg pg.29). The eyes of Horus on the exterior of the Middle Kingdom coffins were not only intended to provide the deceased’s spirit with passage to the afterlife but also provide protection during this transition. The bracelets found on the king’s wrists and also on that of the Middle Kingdom coffins both support the Egyptian idea that the Wedjat eyes were intended to protect both the body and spirit with the Sun God Horus’s divine power. Ancient Egypt is known throughout history for the monumental structures that they constructed and the glorious art they created. To the Egyptians, life itself was merely a prelude to the next and more important phase of existence; the afterlife. Without the afterlife the Egyptians would see life as pointless and would most certainly not have such elaborate burial rituals and customs or intricately designed sarcophagi and tombs. Through the divine powers and ever watchful eye of the Gods they worshipped the Egyptians believed that they could reach the afterlife; they needed merely to properly prepare themselves and they would be guided there when their time came. Horus is just one of many Gods whom the Egyptians relied on for guidance in life and death. Many beautiful examples of art were created to show the Egyptians devotion to the Gods, and how without his guidance their spirits would be doomed to have no place to call home when their bodies could no longer house them. Bibliography Dunand, Francoise, and Roger Lichtenberg. Mummies and Death in Egypt. Ithica and London: Cornell UP, 2006. Print Hornung, Erik, and Betsy M. Bryan, eds. The Quest for Immortality Treasures of Ancient Egypt. Munich: Prestel, 2002. Print. Assmann, Jan. The Mind of Egypt. New York: Henry Holt and, 2002. Print. Shaw, Ian. Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford UP, 2000. Print. Crimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992. Print. *I changed my thesis to be more specific in terms of the Wedjat and its connection to burial and mummification centered art. Also I may swap out my last two sources if I come across better information in other texts.