Period 2

advertisement

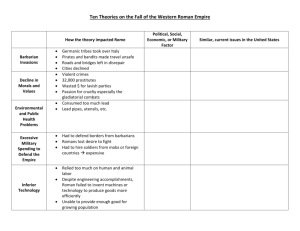

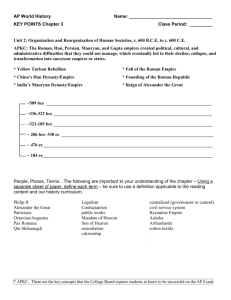

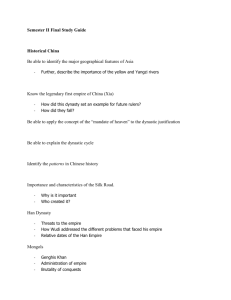

APWH PERIOD 2 REVIEW ORGANIZATION AND REORGANIZATION 600 BCE–600 CE The last unit was all about civilizations, so we're leveling up in this unit to what you can think of as "civilizations plus"—also known as empires, or those giant military structures that conquered most of the ancient world. In this unit, we cover some of the most recognizable empires in all of history. It's pretty sweet, we're not going to lie. The Big Changes If you're looking for a major change, the rise of massive empires should be your ticket to glory. This is not to say that earlier societies didn't have forms of political organization or ambitions to expand; they simply couldn't hold it together like the empires of this period. Empires in this period became ridiculously massive, with the largest, the Achaemenid Empire, ruling over a full half of the world's population. To keep these empires together, there had to be huge innovations in the techniques used to govern. In addition, empires tried to spread their culture to the people they conquered, leading to a massive expansion and codification of cultural and religious traditions. Many of the world's great philosophers also lived during this time. The Big Continuities All this culture and philosophy didn't suddenly spring up out of nowhere. Philosophers were often building on ideas already thousands of years old in their cultures. Many of the philosophies and religions developed in this period had roots going back to the Neolithic era. HUMANS AND THE ENVRONMENT Rise of the City: Home Is Where Everyone Else Is Look, you all know what a city is, and we feel kind of dumb explaining it. It's like telling you that ice cream is cold—and also creamy. You get it. However, it's also worth noting that the rise of those early cities, while less sophisticated than they are today, happened to overlap with the rise of massive empires. Coincidence? We think not. Most of the major empires of this period grew around the all-important capital city. These cities became hubs for commerce, trade, and politics—a transition that had a lot to do with the influx of people to urban areas. Suddenly, tons of folks were squishing together into incredibly small (and unhygienic) spaces...voluntarily. What gives? Like today, people were drawn to cities by the idea of economic opportunity. Cities had marketplaces, and marketplaces meant jobs, plain and simple. With all of this transacting and living going on in ancient cities, however, it became increasingly clear that people needed laws to make sure that complete strangers could live in such close proximity without killing each other at the first opportunity. Disease: Dancing in the Street, with Germs People might not have had to worry about getting killed by their neighbors, but disease was lurking around every corner. (And in the piles of human waste, and also in dead bodies. Super sanitary.) More people brought an equal increase in the amounts of waste and trash—which cities didn't always know what to do with—so bacteria and viruses had countless opportunities to thrive. This period saw the ancient world's first recorded pandemics. There were at least three recorded strains of plague or water-borne illnesses that swept across the Eurasian trade routes, killing upwards of 10% of the world's population. CULTURE Some of the world's most well-known religions gained popularity during this period when people started asking the questions that really matter in life: Who am I? Where did I come from? What's for dessert? You know, things like that. In this section, we'll go over some of the major religions that shaped this era, as well as other forms of cultural expression in the world. Hinduism In the previous unit, we talked about Vedism, a loose collection of different polytheistic beliefs that thought it was important to read and recite specific texts called the Vedas. In this period, as writing became more common, a whole bunch of new texts joined in to the tradition and gave rise to Hinduism, an even more complex and diverse set of beliefs. The chief deity of Hinduism is Brahman, considered to be the ultimate transcendent reality behind all things. Brahman is believed to incarnate itself as a large pantheon of gods and goddesses. Some Hindus sought to get in touch with the source by attempting to find the part of Brahman within themselves. They did this through meditation and yoga. Others tried to get in touch with Brahman through devotion to one of the gods or goddesses who were believed to be Brahman incarnate. There were few central authorities of religious figures, and it was generally accepted that there was no absolute best way to get in touch with Brahman. Despite all this diversity, all forms of early Hinduism had elements in common: 1. They believed in the concept of dharma, which refers to duty or destiny. 2. Like the Vedics, they also believe in karma, which is a running tally of actions that come back to affect you later on in life. (The popular conception of karma has to do with the idea of getting what you deserve, which isn't too far off the mark. Think about it as a kind of cosmic cause-and-effect relationship.) 3. Another key concept Hinduism inherited from Vedism was reincarnation, or the idea that the spirit comes back after death in a new body or in a different plane of existence. Many early Hindus also believed in an idea called jati, or occupational group. In early societies, because kids learned their trade from their parental units they usually stayed in the same profession as their folks. In many forms of Hinduism, this was believed to be the result of some families having a different dharma, or destiny, than others. As a result, Indian society was defined as having thousands of jati, like farmers, shoemakers, brickmakers, warriors, etc. Different areas of India had different divisions of jati, and many Hindus rejected the idea altogether. But by the very end of this period, in North India, the jati had been organized into four wide groups: priests, warriors, freemen/landowners/merchants, and peasants/servants. Below these were those people not considered to be part of society: slaves and foreigners. Historians noted this was similar to a later Spanish colonialist system of racial division, called the "caste system," and also applied this term to the North Indian Hindu division of society. However, it was not until later years that this caste system was enforced, and even then it never applied to all of India. Genetic analysis has also shown that there was significant intermarriage between castes up until recent years. Buddhism Remember how we said that many Hindus tried to get in touch with the divine by meditating? Every now and then, a group of meditating yogis would develop beliefs so different from other Hindus that they came to be seen as a new religion. Among these groups were the Jains, who are as vegetarian and self-sacrificing as it is possible to be. Another is the Tantrics, whose rituals for getting in touch with divinity could be a little saucy. However, by far the most successful offshoot of meditative Hinduism was Buddhism. Buddhism was founded in India by a former prince named Siddhartha Gautama, who lived from around 563 to 483 BCE. He would later be called the Buddha. Like the Hindus he grew up with, Siddhartha believed in karma and reincarnation. Unlike other Hindus, he did not believe that endless reincarnation was a good thing because even the best possible life had a lot of pain. Siddhartha is said to have meditated on this problem under a Bodhi tree in the wilderness for decades (pretty impressive considering we have trouble sitting still for anything above five minutes). In the end, he achieved what he called enlightenment, a state where he was able to shed his individual consciousness and identity. He believed that, now that he was enlightened, when he died he would enter into a state of nirvana, or "freedom from rebirth." Free from an individual consciousness, he felt he was free forever from worldly suffering. Before he died, he taught many to follow his path to enlightenment by learning what were called the Four Noble Truths: 1. 2. 3. 4. All of life is suffering. Suffering is caused by desire. There is a way out of all the suffering. The way out is known as the Eightfold Path. The Eightfold Path basically says that if you have the right intentions in your understanding, purpose, speech, conduct, livelihood, effort, awareness, and concentration (that's eight—count 'em), then you're on the path to finding your way out of suffering and achieving nirvana...without the assistance of gods or priests. Buddhism got a huge bump from Ashoka, a ruler of the Maurya Empire, who converted in around 270 BCE after a really bad night out and helped spread the religion through his empire. Through the efforts of missionaries, Buddhism also expanded to the rest of Southeast Asia as well as East Asian countries like China, Japan, and Korea. Buddhism underwent significant changes as it spread from region to region, so that the doctrines of Chinese, Tibetan, Central Asian, and Indian Buddhism are all distinct from each other. Confucianism First things first: Confucianism isn't actually a religion. Not even close. As an ethical system, Confucianism doesn't deal with questions of the afterlife, spirituality, or divine authority (or dessert, in case you were wondering). Confucianism played an extensive role in Chinese history, however, so it's worth our time to take a closer look. The system is named after Confucius (aka Master Kong), who lived from 551 to 479 BCE during the Spring and Autumn Period, in which China was divided up into hundreds of duchies. Unlike other philosophers of the time, Confucius thought that any discussions about the afterlife or the gods were pointless. He felt that if humans wanted to make their lives better, they would have to do it themselves. Confucius also thought that human society was perfect back in the good ol' days of the early Zhou and Shang Dynasties. Accordingly, he taught that by following the model of the ancient states of China, contemporary people could find happiness and peace. Specifically, Confucius thought that everyone would be happy if they knew their exact place in society. Rulers were to be given the absolute loyalty of their subjects, but they were also to use their power to protect and support their people. Confucius outlined other similar hierarchical but mutually beneficial relationships that he thought were essential to society: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Ruler to subject Father to son Husband to wife Older brother to younger brother Friend to friend Whether or not people agreed with the whole superior-inferior thing, every individual needed to act fairly and take responsibility in his or her relationships. Confucius argued that if everyone followed suit, bam…harmony. Confucianism did not immediately catch on, but there were enough of Confucius's disciples and descendants to keep the philosophy alive for centuries. Confucianism finally became the state ideology in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), and remained the official ideology for all subsequent Chinese states. Its principles continue to influence much of Chinese culture today. Daoism Daoism has often been a kind of counterculture to Confucianism. While Chinese government officials practiced Confucianism at work, they often liked to expand their minds with Daoism on their days off. Daoism is one of the grooviest outlooks on life to come out of this era. According to Laozi, the (probably mythical) founding teacher of Daoism, life is all about the Dao, or "the way of the world." Daoism emphasizes the importance of following the natural order of things. It emphasizes the importance of non-action, silence, and just generally going with the flow. Think of it this way. When in doubt (Daobt?), imagine Laozi sitting barefoot in the woods somewhere with a flower in his hair, telling everyone to take it easy, man. Like Confucianism, Daoism started out as a philosophy rather than a religion. However, as time went on, Daoism began to be associated with the worship of a certain type of god, called an immortal. Immortals were previous humans who achieved divinity through drinking an alchemical elixir of immortality. Religious Daoism hit its peak during the 1st millennium CE, and is now modern China's fifth largest religion. Greco-Roman Philosophy On the other side of Eurasia, in Greece, a number of philosophers were also coming up with philosophies that would influence the world until the modern day. Probably the most important of these was Socrates (469–399 BCE), whose ideas were written down by one of his students, named Plato, in a book called The Republic. Socrates, like Confucius, believed that any attempts to discern what the gods wanted or even if they existed was futile. Also like Confucius, Socrates believed that, in the absence of reliable help from the gods, people would have to build an ideal society by themselves. Socrates proposed that everything should be rationally examined and societies should be self-critical. However, he might not have been all that rational himself (from a modern perspective), as he was extremely racist, sexist, and strongly opposed to the idea of democracy. He was eventually executed, ironically, by popular vote of the democratic citizens of Athens. Socrates' philosophy was taken up by other Greeks, notably his student Plato and the later philosopher Aristotle. These philosophers were the prime influences of philosophers in the Roman Empire. Together, the Greco-Romans built a large body of what is today called classical philosophy, with an emphasis on logic and empirical observation. Christianity Christianity is based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, a Jew who lived in Israel during the Roman occupation. His followers believed he was the Messiah, or the Jewish leader who had been prophesied for generations. He preached an extension of the Ten Commandments and focused his message on the love of God, neighbor, and self. Jesus was born around the year 6 or 4 BCE (in fact, the beginning of the "Common Era" that we refer to in dates marks what was previously believed to be the year of Jesus's birth) and was crucified by the Romans in the late 20s or early 30s CE. The tenets of Christianity come from the writings that were recorded after Jesus's death. These appear in the text that we know today as the New Testament, which builds on the Jewish holy book, which Christians call the Old Testament. Jesus's message emphasized the importance of breaking down some of the traditional stratifications in society, and he welcomed the faith of prostitutes, lepers, and tax collectors—people who were generally loathed by larger society. Christianity was considered a fringe religion in ancient Rome, so Christians were often persecuted until the Emperor Constantine made the religion legal in 313 CE. The combination of this official acceptance and the religion's emphasis on conversion marked the beginning of Christianity's tremendous influence in Europe and the rest of the world, a status the religion still holds today. After Christianity became accepted, it became organized. The bishops of major cities like Rome, Constantinople, Antioch (in Syria), and Alexandria (in Egypt) got together and decided on an official version of Christianity, called Orthodox Christianity. Types of Christianity that didn't agree with Orthodox Christianity were called heretical and shunned within the Roman Empire. One of these types of Christianity, called Nestorian Christianity, found a new life outside the Roman Empire and became a minority religion in Persia, Central Asia, and China. The Rest The examples above are just the big ones that had an impact on later periods. However, it's hardly a complete list of all the thinkin' and prayin' that was going on at this time. There were substantial philosophical and religious developments in Africa and the Americas as well! Religions in SubSaharan Africa and South America incorporated previous beliefs like ancestor worship with new gods and philosophies. Unfortunately, many of these traditions have been lost, so it is difficult in the modern day to know exactly what they were all about. Inventions, Art, and Architecture, Oh My! We've been talking a lot about the historical record, but many early civilizations left their histories in the form of art, architecture, and other innovations. AP World History loves to throw some of these details into the exam, so here's a quick rundown of some of the biggest cultural developments of the period: In China, the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) is famous for building the Great Wall, although most of the Wall has been torn down and rebuilt several times since. The subsequent Han Dynasty invented paper. Early Chinese mathematics and engineering also took off in this period, often used to construct or attack massive city fortifications. Rome needed a way to control its enormous and sprawling empire, so it decided that the best way to do so was to make everything just a little more Roman and a lot more orderly. They built aqueducts to transport water, roads that led back to Rome, and huge buildings for both government and entertainment. Along with the Greeks, the Romans also made a number of advancements in art, math, and philosophy. In India, the Gupta Empire (320–550 CE) is often thought of as the launching point for later Indian society. The Gupta Empire made huge advancements in algebra and geometry, setting the stage for later Indian mathematics. The Gupta math geeks were the first in Eurasia to come up with the concept of zero. Even more importantly, Gupta arts, literature, poetry, and music were the primary influence of later Indian culture. The Gupta are also known for building huge temples that feature Hindu gods, and for inventing the earliest known version of the game of chess. STATE BUILDING Rome, Greece. Maurya India. Gupta India. China. Persia. Before we get started, it's crucial to know how to define an empire as opposed to something like a modern-day nation-state. An empire is a large political organization that typically unites people of different geographies and ethnicities, and the structure of the government funnels authority to a single dominant authority. As the heads of their empires, emperors have historically held so much personal power that their subjects frequently thought they were divine. It may be good to be the king, but it's great to be the emperor. While you won't be expected to know every detail about every empire for the AP World History exam, it's a good idea to familiarize yourself with the most important ones. (Rule of thumb: if there's a movie about a particular empire, it's probably important.) Pay particular attention to the major details, note the way each empire rose and fell, and think about the similarities and differences between empires from around the world. We're going to be looking at some of the most significant empires in all of world history, so welcome aboard and keep your hands and feet inside the vehicle at all times. This is going to be one crazy ride. Persia: C'mon, Guys…This Is Getting Ridiculous The big dog among Persia's empires was the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE), which was the empire that just kept getting bigger and bigger. And bigger. It encountered small kingdom after small kingdom, absorbing them into the empire wholesale without altering local culture or power structures. Around 500 BCE, the Achaemenids set a yet-to-be-broken record by ruling over roughly 50% of the world's population. From a capital called Persepolis in Iran, they ruled an empire that included what is now Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, north Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and southern Russia. Each area was more or less left to administer themselves, so long as they sent taxes every year and military units whenever the empire was at war (which was often). This extremely decentralized model allowed the Achaemenids to expend a minimum of effort to maintain their empire. The downside of all this was that the only thing holding the empire together was the threat of military action. It was kind of like Panem in the Hunger Games in that it used the troops from some conquered areas to frighten other conquered areas into submission. It was an empire built on a pretty shaky foundation. Around the 5th century BCE, they tried to unify the empire religiously by making Zoroastrianism the empire's official religion. However, it didn't really take. When the Greco-Macedonian leader, Alexander the Great, beat the Achaemenid army in the 4th century BCE, local rulers across the empire declared their independence. Not long after, Alexander took Persepolis and brought the giant Achaemenid empire down. The Achaemenids are most famous in popular culture from the movie 300, which is based on the Battle of Thermopylae between the invading Achaemenid ruler, Xerxes, and a Spartan king, Leonidas. But here's the deal with 300: pretty much everything in that movie is absurdly historically inaccurate. This includes the reasons for the war (it wasn't really a battle between democracy and theocracy), most of the depicted Spartan culture (Spartans weren't actually homophobes who hated the rest of Greece, nor was their society "free" by any sense of the word) the depicted Persian culture (they were actually Zoroastrians and kind of uptight and prudish ones at that) the technology involved, and even the number of soldiers in the title (for most of the battle, the Spartans were leading thousands). Also, most of you shouldn't watch it because it is rated R, and we know you'd never dream of disrespecting the Motion Picture Association Film Rating System. However, this movie is a great segue to Greece. Greece: C'mon, Guys…Pull it Together Before Alexander the Great, there hadn't been a "Greek Empire" per se. In fact, ancient Greece was mostly organized into city-states (or the Polis) and you've probably heard of a few of these names before. We're talking about Sparta and Athens here, people! So epic. It's hard to generalize about Greek culture because each city-state had a distinct personality, so to speak, but we can say with certainty that the region profited from trade above all else. Since they lived on a peninsula and a bunch of islands in the Mediterranean, the Greeks sailed from city-state to city-state (not to mention city-state to empire) in order to gain goods, knowledge, and slaves. That famous Athenian democracy only went so far, after all. You might be familiar with ancient Greece from all those myths about the drama between Zeus and Hera, but the AP World History exam doesn't cover the best topics in depth. We'd love to recount stories of those crazy gods, the early Olympics, or King Leonidas, but here are the basics: Athens and Sparta were the two main city-states, and they were what anyone today would recognize as frenemies...with spears. When they weren't fighting together against outsiders like the Persians, they were fighting against each other. The worst fight they had was called the Peloponnesian War, a frankly ridiculous conflict that went on for 27 years. By the time the war ended, neither Athens nor Sparta was in any shape to fight effectively against anyone else. In the 300s BCE, Philip of Macedon conquered all of Greece—but instead of destroying Greek culture, the Macedonians embraced it. Philip's son, Alexander, was raised in Greece and embraced much of Greek culture. When he grew up, Alexander took Greece on the road, conquering a large portion of the disintegrating Achaemenid Empire. He spread Greek culture across the entire breadth of his Central Asia like some kind of ancient Johnny Appleseed. Except with fewer apples, obviously, and more conquering. After Alexander's death at the age of 32, however, the lack of leadership led to a power vacuum. In Central and South Asia, his former generals founded new kingdoms that combined Greek, Persian, and Indian culture. In much of the region, Alexander is still seen as a cultural hero in modern times. Back in Greece, some generals established small kingdoms, but they eventually fell apart into loose confederacies of city-states. They were wide open for conquest by the Romans in the 2nd century BCE. Rome: C'mon, Guys…Stop Copying Greece Rome is often associated with ancient Greece because the two cultures shared a significant overlap in culture. Like Athens and Sparta, Rome began its life as a city-state on the Italian peninsula. Its successful expansion brought it in conflict with Carthage, a large Phoenician city in modern-day Tunisia, Rome fought a series of epic battles against the Carthaginian general Hannibal and his forces. (We know we're using the word "epic" a lot here, but what can we say? Ancient empires were epic. So were many of the poems that described their various exploits.) After the Romans dominated the Carthaginians—even though the Carthaginians threw out all the stops and rode elephants into some battles—they continued to dominate and eventually took over almost all of Europe. Ancient Rome was divided into two broad categories: the patricians and the plebeians, or the rich and the average Josephuses. The patricians owned most land, held most of the power, and lived mostly sweet lives. To top it off, their votes counted for more than the plebeians' did. The plebeians were essentially commoners who spent most of their time farming, fighting in wars, and trying to survive. The slaves, as usual, ranked below everyone else and were treated like dirt. Rome, like Carthage and several other Mediterranean cities, was run as a Republic. Unlike ancient Athens, where citizens voted together on every issue, Republics worked by having people elect representatives every few years. In the 1st century BCE, through a series of coups, the Senate lost most of its power. Instead, Rome came to be run by hereditary emperors called Caesars. For the first few hundred years, Rome excelled at being an empire. The Romans conquered almost everything they could get their hands on—which, let's face it, was a lot of stuff—and achieved both internal peace and dazzling new cultural heights. The Romans took the opposite approach to the Achaemenids. Instead of leaving local power structures in place, they usually broke down local power structures to set up their own. Local kings were replaced by Roman governors, and the whole empire was made to follow Roman law. All good things must come to an end, however, and ancient Rome eventually did as well. Emperor Constantine, the same guy who made Christianity legal, also moved the capital from Rome to Constantinople, in modern-day Turkey, to keep a closer eye on the source of Rome's money, the Middle East. For generations afterwards, there was an escalating power struggle between Constantinople and Rome. By the end of the fourth century CE, the two capitals split the empire in half between them, creating the Western Roman Empire and Eastern Roman Empire. The Eastern Roman Empire, also called the Byzantine Empire, lasted another hundred years, but the Western Roman Empire was on its way out. They had the less profitable half of the empire and had some serious problems with money flow. Eventually they buckled under the invasions of tribes like the Huns from Central Asia and the Goths from Scandinavia. Maurya and Gupta India: C'mon, Guys…Leave Better Records The Maurya Empire is named after Chandragupta Maurya (340–293 BCE). Apparently, naming things used to be just that simple. Chandragupta got his start as a vassal of Alexander the Great. Intending to place Chandragupta as the ruler of North India, Alexander gave him large amounts of wealth and power. Though Alexander's invasions of India failed dramatically and he died soon after, Chandragupta kept trying. Eventually he conquered most of modern-day India, Pakistan, and parts of Afghanistan and Burma. The empire flourished from 321 to 180 BCE, including the weird and wonderful reign of Chandragupta's grandson, Ashoka. As an emperor, Ashoka was most famous for consolidating his empire's hold on western Burma and Sri Lanka very, very, violently. As the story goes, he woke up one day to find himself repulsed by the aftermath of a particularly gory evening and converted to Buddhism. Despite the drastic change from brutal conqueror to meditative Buddhist, Ashoka pulled off the switch and oversaw a thriving culture. He spread his newfound religion throughout the land. The post-Ashoka Maurya Empire was the high point for Buddhism in India. The Mauryan Empire, compared to the Achaemenid or Roman Empires, left comparatively few records. However, a lot about their government system can be deduced by "rock edicts," big stones carved with the pronouncements of Maurya emperors. These pronouncements show that the government was fairly centralized and employed thousands of public servants. The Maurya government appears to have used their vast numbers of employees to complete large-scale public works projects, like roads and irrigation canals. However, the Maurya emperors' grips were either too tight or not tight enough, because their empire didn't have the staying power of the Romans or Achaemenids. Their empire fell apart into several warring kingdoms. Northwest India was conquered by invading Greco-Bactrians, the descendants of one of Alexander the Great's armies. North India was not reunited until 320 CE by Chandra Gupta, who founded the Gupta Empire (320 CE to 550 CE). As already mentioned, the Gupta Empire was a time of tremendous cultural accomplishment in India. And, similarly to the Maurya Empire, the Gupta established a huge administrative bureaucracy to oversee the whole empire from the top down. They seemed to have figured out how to avoid the same kind of collapse as the Maurya Empire and were still going strong up until their invasion by the White Huns in 550 CE. Unfortunately, they just weren't strong enough to fight off the White Huns. Qin and Han China Remember the Zhou Dynasty from the last unit? It was founded by Iron-Age pastoralists who conquered the Shang kingdom in central China. Well, about halfway through the Zhou Dynasty, in the 8th century BCE, the Zhou kings lost all real power and China became divided into hundreds of duchies. In 475 BCE, many of these dukes declared themselves to be kings and began trying to conquer the rest of China. In 221 BCE, the erstwhile King of Qin went on to consolidate China into a new empire and start what he called the Qin Dynasty. He promoted himself from king to emperor, a title previously only applied to mythical figures. The first Emperor of Qin's dynasty was huge, effective, and occasionally scary beyond all reason. He banned Confucianism and made the state ideology Legalism, which was very similar to modern totalitarianism. However, he also instituted a single written language, standardized weights and measurements, and built massive public works projects like roads, canals, and the Great Wall. He also built some massive "private" works projects, like a giant army of clay soldiers for his tomb. These things don't come cheap, though, and the first emperor bankrupted the state. To almost nobody's surprise, a massive civil war broke out almost immediately after his death in 210 BCE, and it took nearly a decade for a new leader to emerge and create the Han Dynasty. Unlike most other dynasties in the world, the Han Dynasty was not named after the ruler (whose family name was Liu) but after the home territory of the ruler. Following this, all Chinese dynasties were named either after regions of China or were poetic descriptions of the new state. They went on to create an efficient bureaucracy—one of the most important legacies of the Han Dynasty, in fact. Their bureaucracy ran very similarly to modern governments, with pay grades, benefit packages, and promotions based on experience. In addition to pulling that off, the Han also reaped the benefits of the First Emperor of Qin's work without creating a bunch of internal enemies in the process...and managed to last a solid 400 years. Eventually, however, the Han Dynasty collapsed for many of the same reasons that Rome collapsed: revenue problems and foreign invaders. Some of these empires really should have compared notes. Teotihuacan, the Maya, and the Moche: The Other Side of the Pond In Central America, the Olmec were on their way out. Due to environmental changes, the Olmec heartland around what is now Veracruz was drying out, and the Olmec population dropped compared to their neighbouring areas. The big successor to the Olmec was the Maya. The Maya had been around for a while as neighbors and subjects of the Olmec. However, around 250 CE, the Maya became the dominant civilization in the region. Like the Greeks, the Maya weren't so much an empire as a collection of city-states. Each city-state maintained a network of slash-and-burn farmers who supported its population. Near the Maya areas, in southern Mexico, was a metropolis called Teotihuacan. This was at the time one of the largest cities in the world, with a population between 150,000 and 250,000. Teotihuacan had considerable influence, both cultural and political, over the Maya city-states. It was also thought of as the cultural capital of Central America for over a thousand years, even after it declined into ruin. Teotihuacan can maybe be thought of as the "Athens" of Central America. In South America, the most advanced civilization was on the coast of Peru and in the lower Andes, near to where the Chavín used to be. This is called the Moche culture, and, like other Andean culture, the lack of written records makes it difficult to determine exactly what their deal was. Their culture was focused on agriculture, with cities much smaller than those in Central America. However, there appears to have been large governments for at least some of the period, as evidenced by large-scale public irrigation projects. In an Imperial Nutshell Empires rose and fell during this era, and while each empire had its own story, we can still identify a few common—and epic!—threads. For starters, empires typically expanded through military force...something that often created problems later on when the conquered parties decided it was time for a little conquering of their own. After unification, successful empires tended to create strongly centralized governments that revolved around authoritative leaders and ran like well-oiled machines, clearing the path for incredible cultural achievements that still resonate with us today. Nothing lasts forever, though, and even the most dazzling and unified empires of this period eventually collapsed. In fact, we can't really think of any empire in history that didn't end in—you guessed it, epic—tragedy. Okay, we're really done with the epic thing now. Promise. ECONOMICS Trade Your Way to Success (or At Least China) These giant empires gave rise to even more giant trade networks. The large, continent-spanning empires of the Achaemenids and Alexander the Great created a large zone where merchants could travel in relative safety, without having to worry about accidentally crossing into warring or unstable kingdoms. During this period, trade networks developed that moved goods between India, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. By at least the beginning of the Han Dynasty, Chinese merchants had linked up with Central Asian merchants through overland routes in northwest China, and sea routes between southern China and India. Sea routes also developed between India, the Middle East, and East Africa across the Indian Ocean, and between North Africa, Spain, Italy, Greece and the Middle East on the Mediterranean Sea. Finally, trans-Saharan trade routes linked West Africa to North and East Africa. As a result, most of Afro-Eurasia was involved, sometimes distantly, in one huge sprawling trade network. Many goods made the whole trip across. Roman glassware, metal objects, and coins made it all the way to China and Chinese silk made it to North Africa and beyond. Food crops spread across the world, with wheat agriculture beginning in China and rice being grown in the Middle East. Agricultural techniques spread, increasing global food production. Religions also spread along the trade routes. Buddha may have rejected material possessions, but that didn't stop merchants from spreading Buddhist scriptures while out trading material possessions. Christianity spread into Central Asia and became particularly popular among Persian merchants. Hinduism spread along sea routes to Southeast Asia. The explosion of trade led to several innovations in transportation. Across Afro-Eurasia, people began breeding a large number of domesticated pack animals. These included horses, oxen, and, in dry areas, camels. Rulers also encouraged this trade by developing roads and canals to help merchants move goods. At sea, new sea routes and wind patterns were discovered and mapped. There were also improvements in shipbuilding technology, including the development of the first ships able to tack against the wind. SOCIAL STRUCTURES First Comes Law, Then Comes Order After Hammurabi and the Babylonians, which we're calling right now as an awesomely epic band name, Rome was the next civilization to focus on the importance of laws (and, of course, following them). The policy was probably a good one: Rome spread across so much of the ancient world that it would have been almost impossible to control the far reaches of its empire without some kind of standardized legal code. To promote internal peace, the Romans drew up the Twelve Tables and stuck them up in the Roman Forum so everyone could see them—especially the plebeians, who were usually the ones who got dinged the most by Rome's unofficial constitution. Along with a bunch of rules for going to court and parent-child relationships (once your dad tries to sell you into slavery three times, it's totally fine to leave home), the Romans were the ones who first came up with the concept of being innocent until proven guilty. Hierarchy: Like the Food Pyramid, but with People To nobody's surprise, society was still divided into super-tight cliques during the age of empires. And by "cliques," of course, we mean "social classes that you are stuck in from birth to death." This is going to be the theme for a few more centuries, so you might as well get used to it now. Basically, people were divided into leaders and commoners. Many societies believed that their rulers were somehow connected to the gods, if not divine themselves, which rulers in Europe would eventually use to justify the concept of absolute monarchy. (Yes, Louis XIV of France, we're looking at you.) Below them were often the warrior class, the priests, the merchants, and the peasants— usually in that order, which is one of the most important elements of hierarchical social structure. The other important thing about hierarchy is the fact that there was little to no social mobility. People rarely married or mingled outside of the social class in which they were born, whether in ancient Rome or Han China, which was great for the elite, of course, but something of a downer for everyone else. KEY TERMS Qin Dynasty: Ruled China from 221 to 207 BCE. It was notable for reuniting the old Zhou kingdom as well as conquering several new areas of central China. It was also notable for standardizing weights, measures, writing, and for building the Great Wall. Qin Shi Huangdi: Literally, "The First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty," this dude was also the first nonmythical person to take the title of "Emperor" in China. Han Dynasty: Ruled 206 BCE to 220 CE. This Confucian dynasty established a long period of unity in China. They are notable for completing the Qin's standardization of language, creating the system of Chinese characters used up to the modern day. They also established the precedent of a large, self-regulating bureaucracy. Confucianism: The official ideology of Chinese courts from the Han Dynasty until 1911. It places an emphasis on hierarchy, education, and just governance. Founded by Confucius (551–479 BCE). Daoism: Originally a philosophy founded in the sixth century BCE, Daoism has since accrued many spiritual and religious aspects. It emphasizes being in harmony with oneself and nature. Legalism: The official ideology of the Qin Dynasty. Very similar to totalitarianism, it places an emphasis on the need for the government to harshly punish or execute people for the smallest moral infractions. Silk Road: A network of land and sea routes connecting China with the rest of Afro-Eurasia. Hinduism: A very diverse religion with many vastly different denominations. Hinduism developed out of Vedism and places value of communing with Brahman, the divine "reality" underneath the real world. Siddhartha Gautama Buddha: The founder of Buddhism, lived from 563 to 483 BCE. Buddhism: An offshoot of Hinduism, Buddhism centers on escaping from the endless cycle of reincarnation through shedding individual consciousness. Caste system: A term later applied to the Hindu concepts of jati (occupational group), in which persons born into one occupation were considered destined to perform that occupation. Ashoka: A ruler of the Maurya Empire in India, Ashoka is most known for converting to and spreading Buddhism. Lived from 304 to 232 BCE. Maurya Empire: The first empire to unify most of India, Pakistan, and Burma. It lasted from 322 BCE to 185 BCE. Gupta Empire: A large and influential Indian empire, it ruled Pakistan and the north of India from 320 to 550 CE. Polis: Greek name for an independent city-state Athens: A large and powerful city-state. Athens was known for a limited form of democracy in which a small portion of the population (male landowners) voted in the public square on every major issue. Sparta: Another large and powerful city-state. It was ruled by kings, who were sometimes selected by a general assembly. All male Spartan citizens trained for the army, leaving work to the slaves (two-thirds of their population). Alexander the Great: A Macedonian ruler raised in Greece. He would later conquer most of the Achaemenid Empire. Hellenism: The Greek cultural influences seen in the Middle East, Central Asia, and India following Alexander's conquests. Roman Republic: The government of early Rome, in which citizens voted on senators to represent them. Overthrown by a series of dictators in 27 BCE. Roman Empire: The new government after 27 BCE, in which the Senate was subservient to an emperor. Constantine: Ruled the Roman Empire from 306 to 337 CE. Legalized Christianity and built a new capital at Constantinople. Jesus of Nazareth: Lived from 6 BCE or 4 BCE to the late 20s or early 30s CE. Founder of Christianity. "Jesus" is actually the Greek form of his name, which was the Hebrew name Yehosua (Joshua). Maya: Culture of several city-states in southern Mexico and Central America. Declined in the 8th and 9th centuries CE.