Acute Transfusion Reaction Module Created by Michael Reyes MD

advertisement

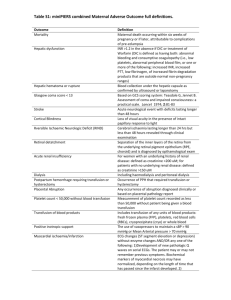

Acute Transfusion Reaction Module Created by Michael Reyes MD, and Sara Koenig MD 4/14 Objectives: 1. Become familiar with the assessment and work-up of acute transfusion reactions 2. Develop a differential diagnosis for acute transfusion reactions 3. Understand the pathophysiology and management of transfusion related acute lung injury (TRALI) References: King, Karen E, et al. Blood Transfusion Therapy A Physician’s Handbook. Bethesda: AABB, 2011. Print. Roback, John D, et al. Technical Manual. Bethesda: AABB, 2011. Print. MKSAP 16 Case A 68 year old male with a history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hypertension, and cirrhosis secondary to alcohol abuse presents to the ED following a brief episode of melena. His medications include fludarabine, lisinopril, metoprolol, and diazepam for occasional anxiety. On physical examination, his temperature is 37.3 degrees Celsius, blood pressure is 150/90 mm Hg, pulse is 90/minute, respiratory rate is 16/min, and O2sat is 97% on room air. There is no scleral icterus or jaundice, however trace bilateral lower extremity edema is present. There is no evidence of ascites. The patient’s spleen is mildly enlarged and non-tender. The patient weighs 100 kg. Labs: Wbc 16, Hgb 11, Hct 33, Plt 80, LFTs: AST: 320, ALT:90, TP 5.3 g/dL, TB 3.1, DB 0.8, Chem7 normal, INR 1.5, PT 15s, PTT 38s The patient is admitted to Blue Medicine and a GI consult is obtained to identify the source of the melena. GI says that they will not “scope” the patient unless the INR is less than 1.5. They recommend FFP to lower the INR prior to endoscopy. What are the common indications for FFP? Fresh frozen plasma is indicated for treatment of active bleeding in patients with multiple coagulation factor deficiencies (often secondary to liver disease, DIC, or dilutional coagulopathy) or in those with multiple factor deficiencies scheduled for surgery or invasive procedures. Other indications for FFP include emergent reversal of warfarin effect in bleeding patients or in those requiring emergent surgery. Recently, prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) such as Kcentra have been approved for emergent warfarin reversal, though many institutions still successfully use FFP. Prophylactic use of FFP to reduce the INR in non-bleeding patients or in those not scheduled for surgery/a major procedure is not recommended. What are some of the potential complications of transfusing FFP? Transfusion of FFP may result in a number of different reactions or complications that vary in etiology and severity. The most common reactions are simple allergic reactions (1-3%, limited to hives and itching) and febrile transfusion reactions (0.1-1%, >1 degree C change in temperature into febrile range). These reactions do not result in significant morbidity or mortality; however differentiation of these mild reactions from more severe ones at the bedside is generally not possible. Thus Laboratory testing (tests for hemolysis, etc.,) and additional studies (chest x-ray etc.) are necessary for appropriate evaluation of suspected transfusion reactions. The most severe reactions associated with transfusion of FFP include transfusion related acute lung injury (TRALI), transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO), and anaphylactic reactions (the most common identified cause is severe IgA deficiency). Infectious risks such as HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B should also be considered with each transfusion, though their incidence has declined drastically with improved laboratory detection (i.e. risk of HIV and hepatitis C transmission is approximately 1/2 million units transfused). Is FFP likely to be helpful in this patient whose melena has resolved? The answer is no. In non-bleeding patient’s with minimally elevated INRs (generally <2), “prophylactic” transfusion of FFP is not recommended. In general, up to half of FFP transfused is done so inappropriately in non-bleeding patients with minimally elevated INRs. This results in little to no benefit to the patient while exposing them to all of the risks of FFP. Multiple studies have shown that the INR of FFP varies between 0.9 and 1.3—thus some units of plasma are actually slightly outside the reference range. Studies have also shown that the lower the INR (i.e. 1.4) the more FFP is required to lower the INR into the normal range. For example, a patient with an INR of 1.5 may require 6-10 units of FFP to lower the INR into the normal range. In contrast, a patient with an INR of 8 may only require 2-4 units to lower the INR to 2-3. Basically, the closer the INR is to normal the more units of FFP will be required to “correct” the INR. What is a therapeutic dose of FFP? A therapeutic dose of FFP is generally considered to be 10-15 ml/kg. Assuming the lower dose (10 mL/kg), our patient would require at least 1000mL of FFP for a therapeutic dose. A unit of FFP generally ranges from 200mL to 250mL, thus 4-5 units would be needed for an appropriate “dose”. Thus the common practice of prophylactically transfusing 2 units of FFP in non-bleeding patients prior to procedures places them at risk with little to no benefit from the transfusion. Does this patient’s FFP need to be irradiated? Although this patient does have an indication for irradiation (CLL), FFP does not require irradiation as it is not a cellular component. Irradiation is required for cellular products (RBCs, platelets, granulocytes) for the following conditions: Lymphoma, leukemia, chemotherapy with potent purine analogues (fludarabine, cytarabine) bone marrow transplant (not solid organ transplant), directed donation to a first degree relative, congenital immunodeficiencies—especially T-cell (no irradiation needed for HIV), and intrauterine transfusions. Despite pleading with GI regarding the lack of an indication for the 2 units of FFP in this patient who is not currently bleeding with a mildly elevated INR, you give in to their request as they will not perform endoscopy without pre-procedure FFP. The patient receives 2 units of FFP. About half way through the second unit of FFP the patient’s nurse notices that he has developed a fever of 38.7 degrees Celsius. All other vital signs are normal, and the patient reports no clinical symptoms. The patient’s nurse calls the Blue Medicine Resident, reports the fever, and asks how to proceed. What is the very first thing you will tell the nurse? When dealing with a suspected transfusion reaction, the first step in management is ALWAYS to stop the transfusion. For most transfusion reactions, including those that may be fatal (acute hemolytic transfusion reaction, anaphylactic reaction, bacterial contamination, TACO, etc.) the greater the amount of product transfused the greater the morbidity and mortality. What further steps should be taken in this suspected transfusion reaction? Once the transfusion has been stopped, management generally consists of supportive measures to assure adequate oxygenation and perfusion until a specific cause of the symptoms has been determined. While supportive measures are initiated, a suspected transfusion reaction form should be filled out and all components associated with the transfusion (remaining unit, tubing, etc.) should be sent to the blood bank. Importantly, all units (and associated tubing) that a patient has received within the last 24 hours should be sent to the blood bank if possible—as transfusion reactions may occur hours after the implicated unit has been transfused. A copy of the suspected transfusion reaction form may be accessed through the UNMH intranet. The blood bank will perform a clerical check, retype the patient and unit, assess for hemolysis of the unit and within the patient sample (DAT, serum hemoglobin), and report the results to the contact provided on the submitted form. A Pathology resident or fellow will call to follow up with the interpretation and any implications for further transfusion or treatment. Importantly transfusions should not be restarted without the results from the suspected transfusion reaction work-up. The only exceptions are simple allergic transfusion reactions (limited to hives and itching that resolve with treatment) and emergent transfusion when there is no evidence of a hemolytic transfusion reaction. If the patient’s condition dictates, other units may be ordered from the blood bank while the results of the work-up are pending (most transfusion reactions are specific to a particular unit—not a particular patient). What is your differential diagnosis at this point? Currently, the only reported symptom for the patient is a fever that developed during transfusion of the FFP. Thus, the differential at this point must include all acute (within 24 hours of transfusion) transfusion reactions that are typically associated with a fever. The differential includes: Acute hemolytic transfusion reaction, febrile transfusion reaction, TRALI, and bacterial contamination. While waiting for the suspected transfusion reaction testing to come back, the patient’s nurse calls you back and says that the patient has developed severe shortness of breath and is requiring supplemental oxygen to keep his O2 sats around 90. Based on the current symptoms, what is your differential diagnosis now? With the development of severe dyspnea, the differential now includes: TACO, acute hemolytic transfusion reaction, TRALI, bacterial contamination, and anaphylactic transfusion reaction. The patient’s underlying medical conditions must be considered in the differential as well. Which studies/lab tests will you order/what other information should be assessed? With the development of SOB, a STAT chest x-ray should be ordered. In addition, a BNP may be helpful—especially if the patient has a pre-transfusion BNP for comparison (may be ordered as an addon to a pre-transfusion specimen if necessary). In cardiac patients an ECG and/or troponins may be considered. Review of the patient’s vitals, conditions, medications, and IV fluids may also aid in diagnosis. Labs to assess for acute hemolysis may be considered (haptoglobin, LDH, urine hemoglobin, bilirubins); however it may be best to await testing results for hemolysis from the blood bank (DAT, serum hemoglobin) before ordering the aforementioned labs. Review of the pre-transfusion vitals and vitals during the transfusion (especially at the time of the suspected reaction) is critical—as this may aid in narrowing the differential. Additionally, vitals may provide an indication of the severity of the reaction. The results of the suspected transfusion reaction work-up and of the other studies are now available, and are as follows: The following studies were negative/no discrepancy: Bedside clerical check, BB clerical check, DAT, serum hemoglobin, ABO and Rh type. The patient’s vitals are as follows: Pre-transfusion: Pulse 84, Temp. 37.3, RR 12, BP 150/92, O2sat. 97% on RA At time of reaction: Pulse 110, Temp. 38.7, RR 28, BP 135/82, O2sat. 80% on RA The chest x-ray shows a bilateral “whiteout” consistent with pulmonary edema. The patient’s pre- and post-transfusion BNPs are similar and within the normal range and a stat ECG shows normal rhythm with sinus tachycardia. Following review of the patient’s symptoms, the suspected transfusion reaction results, vitals, and additional testing, a preliminary diagnosis of TRALI is made. The rationale for the diagnosis is as follows: Development of a fever and shortness of breath is most consistent with TRALI, an acute intravascular hemolytic transfusion reaction, or potentially a septic transfusion reaction. An acute intravascular hemolytic transfusion reaction may be ruled out as the blood bank results evaluating for hemolysis were negative (negative serum hemoglobin, negative DAT, non-discrepant bedside and clerical checks, and ABO/Rh confirmation). Bacterial contamination cannot be entirely ruled out, however it is more commonly characterized by immediate signs of sepsis with the first mLs transfused (severe hypotension, high fever, etc.) and does not routinely result in dyspnea as does TRALI. Additionally, septic transfusion reactions are much more common with platelet and RBC transfusions than with FFP. Although TACO would not present with fever, it should still be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient with severe dyspnea. For the following reasons however, TACO would be much less likely in this patient than TRALI: The patient’s blood pressure actually dropped in association with the reaction (BP usually increases with TACO), the post-reaction BNP was not elevated and did not increase from the pretransfusion value (no indication of cardiogenic pulmonary edema), and again fever is not a symptom of TACO. In patients with suspected TACO and an elevated pre-transfusion BNP, the post-transfusion BNP is much less helpful in establishing the diagnosis. As can be seen, TRALI is a diagnosis of exclusion and other etiologies for a transfusion reaction should be ruled out before a diagnosis is established. Evidence supporting a diagnosis of TRALI include: Acute onset of SOB within 6 hours of transfusion, radiographic evidence of diffuse bilateral pulmonary edema, fever, hypotension (sometimes seen), no evidence of TACO (no increased BP, no signs of volume overload including JVD, no transfusion-associated increased in BNP, no risk factors for volume overload), and no other conditions to explain the findings. Additionally, the dyspnea and hypo-oxygenation of TACO are often ameliorated by diuretics whereas TRALI generally shows no response or may be exacerbated by diuretics. Reaction TACO TRALI Signs and Symptoms Dyspnea, hypertension, pulmonary edema, JVD, peripheral edema, increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure Dyspnea, hypoxemia, fever, hypotension, pulmonary edema, normal pulmonary capillary wedge pressure Studies/Labs BNP (pre- and posttransfusion), chest Xray Usual Cause Rapid/excessive infusion of blood products in at risk patients (CHF, MI, renal failure, etc.) Treatment Stop transfusion, diuresis, supportive care Chest X-ray, BNP (to r/o TACO), labs to assess for hemolysis (r/o hemolytic transfusion reaction) Donor HLA or antineutrophil antibodies Supportive care, intubation if severe symptoms Prevention Avoid rapid or excessive infusion of blood products— especially in at risk patients, use low volume products if necessary Deferral of high risk donors, reporting and deferral of TRALI associated donors ** All signs and symptoms may not be present for any given reaction A diagnosis of Transfusion related acute lung injury (TRALI) is made. The patient continues to deteriorate and requires emergent transfer to the MICU and intubation. The patient’s MICU course is uneventful and following resolution of his pulmonary edema he is eventually extubated. No further episodes of melena are reported during his inpatient stay and he is eventually discharged with an appointment to see GI as an outpatient. Describe the pathophysiology of TRALI Perhaps the most accepted hypothesis for the etiology of TRALI involves infusion of HLA- or granulocytespecific antibodies in high plasma containing components (platelets and FFP). These antibodies stimulate leukocytes in the pulmonary vasculature to release inflammatory substances that increase the permeability of the vasculature resulting in pulmonary edema. This hypothesis would not explain about 15-20% of TRALI cases, so other mechanisms including roles for biologically active molecules in the donor product have been proposed. The true pathophysiology of TRALI may include aspects of multiple proposed mechanisms. Regardless of the mechanism, the end result is a pattern of lung injury that is clinically indistinguishable from ARDS. Is this patient at increased risk of TRALI with future transfusions? As most cases of TRALI are attributed to antibodies in the donor unit, patients who have experienced TRALI are generally at no greater risk than the general population. Thus the risk of TRALI with additional units is about 1/5000 (baseline risk). Though your patient may not be at further risk with transfusion, it is vitally important that the blood supplier be alerted to the reaction in order to identify other products from that same donor that are at a high risk of causing TRALI if transfused. These products are then recalled and disposed of, while the donor will be deferred from further blood product donation. Which blood products are most associated with TRALI? Though plasma and platelet units contain the most donor plasma, and therefore pose the largest risk of TRALI on a per-unit basis, the majority of fatal TRALI cases reported to the FDA are due to RBC transfusions. This is likely because more RBCs are transfused each year than any other component, and targeted risk-reduction methods have been implemented to reduce risk in high plasma containing products. In comparison to a unit of apheresis platelets or plasma, which contains 200-250 mL of donor plasma, RBC units contain only about 20mL or residual donor plasma. How is TRALI managed? TRALI is managed with supportive care to increase oxygenation, with severe cases potentially requiring intubation. Though most cases of TRALI resolve within 48-72 hours with supportive care, the mortality rate remains about 10-15%. In recent years, increased identification of TRALI has led to its recognition as the most common cause of transfusion associated mortality. How have blood banks sought to minimize the risk of TRALI? Due to the increased awareness of TRALI and elucidation of the pathophysiology, blood banks have incorporated measures to decrease the risk of TRALI. The most widespread measure is deferral of all multiparous females wishing to donate plasma-rich products. The rationale for this deferral is that multiparous females are those most likely to harbor HLA- and granulocyte-specific antibodies responsible for TRALI. Associated Hematology Transfusion MKSAP questions for this module: Question 3, Transfusion reactions: Answer E, Washed Question 7, blood types: Answer D, O negative Question 14, TRALI: Answer D, TRALI Question 50, Delayed transfusion reaction: Answer D, New alloantibodies