Basic Training Principles: Overload, Progression, Specificity

advertisement

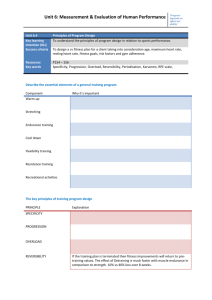

Basic Training Principles Period 2 - Class Definitions Overload In order for the body to increase its fitness, it must be pushed beyond its normal stress. You can apply overload in duration, intensity, weight lifted, and other ways to reach adaptation and excel above it. Progression A gradual increase in workload over a period of time which results in improvements in fitness. Proper rest and recovery are also essential. Diminishing Returns The diminishing returns principle states that when you first begin working out, it is easier to see more in return (weight loss, muscle gain, etc.). As you continue progressing, you will see diminishing returns. Specificity In order to improve a specific skill or in a specific sport, athletic training must focus on those skills. A runner should train by running, a swimmer should swim, and a cyclist should bike. Reversibility Hard earned fitness gains disappear when athletes stop training. Use it or lose it! You'll lose it faster than you gain it. Basic Training Principles Period 5 - Class Definitions Overload The overload principle states that for a person to receive maximum physical gains while working out, they must overwork themselves within reason. Your body will adapt to continually increased stress. Progression In order to progress fitness (body strength, endurance, etc.), you have to have an optimal level of overload in a systematic time frame so you won't over or underwhelm your body. Diminishing Returns When athletes first start training, their fitness levels improve rapidly. But as athletes become fitter, improvement occurs less rapidly because athletes are reaching their genetic limits. Specificity The more specific a workout is to an athlete's desired outcome, the better. Track runners should work on starts and stamina. Reversibility When people stop training, their fitness levels begin to disappear faster than they were gained. Their physical fitness level will decrease unless they maintain a consistent level of fitness. Exercise Science Principles of Conditioning (http://sportsmedicine.about.com/od/training/a/Ex-Science.htm) Get more from your workouts with these exercise principles and guidelines By Elizabeth Quinn Sports Medicine Expert Updated May 16, 2014. In the study of exercise science, there are several universally accepted scientific exercise training principles that must be followed in order to get the most from exercise programs and improve both physical fitness and sports performance. To design an optimal exercise program, workout or training schedule, a coach or athlete needs to adhere to the follow six principles of exercise science. 1. The Principle Of Individual Differences The principle of individual differences simple means that, because we all are unique individuals, we will all have a slightly different response to an exercise program. This is another way of saying that "one size does not fit all" when it comes to exercise. Welldesigned exercise programs should be based on our individual differences and responses to exercise. Some of these differences have to do with body size and shape, genetics, past experience, chronic conditions, injuries and even gender. For example, women generally need more recovery time than men, and older athletes generally need more recovery time than younger athletes. With this in mind, you may or may not want to follow an "off the shelf" exercise program, DVD or class and may find it helpful to work with a coach or personal trainer to develop a customized exercise program. Some things to consider when creating your own exercise program include the next batch of exercise science principles. 2. The Principle of Overload The exercise science principle of overload states that a greater than normal stress or load on the body is required for training adaptation to take place. What this means is that in order to improve our fitness, strength or endurance, we need to increase the workload accordingly. In order for a muscle (including the heart) to increase strength, it must be gradually stressed by working against a load greater than it is used to. To increase endurance, muscles must work for a longer period of time than they are used to or at a higher intensity. 3. The Principle of Progression The principle of progression implies that there is an optimal level of overload that should be achieved, and an optimal time frame for this overload to occur. A gradual and systematic increase of the workload over a period of time will result in improvements in fitness without risk of injury. If overload occurs too slowly, improvement is unlikely, but overload that is increased too rapidly may result in injury or muscle damage. For example, the weekend athlete who exercises vigorously only on weekends violates the principle of progression and most likely will not see obvious fitness gains. The Principle of Progression also stresses the need for proper rest and recovery. Continual stress on the body and constant overload will result in exhaustion and injury. You should not train hard all the time, as you'll risk overtraining and a decrease in fitness. 4. The Principle of Adaptation Adaptation refers to the body's ability to adjust to increased or decreased physical demands. It is also one way we learn to coordinate muscle movement and develop sports-specific skills, such as batting, swimming freestyle or shooting free throws. Repeatedly practicing a skill or activity makes it second-nature and easier to perform. Adaptation explains why beginning exercisers are often sore after starting a new routine, but after doing the same exercise for weeks and months they have little, if any, muscle soreness. Additionally, it makes an athlete very efficient and allows him to expend less energy doing the same movements. This reinforces the need to vary a workout routine if you want to see continued improvement. 5. The Principle of Use/Disuse The Principle of Use/Disuse implies that when it comes to fitness, you "use it or lose it." This simply means that your muscles hypertrophy with use and atrophy with disuse. This also explains why we decondition or lose fitness when we stop exercise. 6. The Principle of Specificity The Specificity Principle simply states that exercising a certain body part or component of the body primarily develops that part. The Principle of Specificity implies that, to become better at a particular exercise or skill, you must perform that exercise or skill. A runner should train by running, a swimmer by swimming and a cyclist by cycling. While it's helpful to have a good base of fitness and to do general conditioning routines, if you want to be better at your sport, you need to train specifically for that sport. Many coaches and trainers will add additional guidelines and principles to this list. However, these six basics are the cornerstones of all other effective training methods. These cover all major aspects of a solid foundation of athletic training. Designing a program that adheres to all of these guidelines can be challenging, so it's not a surprise that many athletes turn to a coach or trainer for help with the details so they can focus on the workouts. One common training method is Periodization Training that it build upon specific training phases throughout the year. Training Principles to Improve Athlete Performance By Rainer Martens (http://www.humankinetics.com/excerpts/excerpts/training-principles-to-improve-athlete-performance) Specificity Principle The specificity principle asserts that the best way to develop physical fitness for your sport is to train the energy systems and muscles as closely as possible to the way they are used in your sport. Thus, the best way to train for running is to run, for swimming is to swim, and for weightlifting is to lift. In sports such as basketball, baseball, and soccer, the training program should not only overload the energy systems and muscles used in that sport, but should also duplicate similar movement patterns. For example, in strengthening a quarterback’s throwing arm, design the exercise to simulate the throwing movement. Warning: This principle can be taken too far. Ample evidence suggests that cross training, or doing another sport or activity, can help improve performance (see the variation principle). Overload Principle To improve their fitness levels, athletes must do more than what their bodies are used to doing. When more is demanded, within reason, the body adapts to the increased demand. You can apply overload in duration, intensity, or both. If you increase a cross country runner’s long-distance run by five minutes, you’ve added an overload of duration. If you instead ask the runner to run her normal distance but in a shorter amount of time, you’ve added an overload of intensity. Progression Principle To steadily improve the fitness levels of your athletes, you must continually increase the physical demands to overload their systems. If the training demand is increased too quickly, the athlete will be unable to adapt and may break down. If the demand is not adequate, the athlete will not achieve optimal fitness levels. Diminishing Returns Principle When unfit athletes begin a training regime, their fitness levels improve rapidly, but as they become fitter, the diminishing returns principle becomes law. That is, as athletes become fitter, the amount of improvement is less as they approach their genetic limits (figure 13.9). A corollary to this principle is that as fitness levels increase, more work or training is needed to make the same gains. As you’re designing training programs, remember that fitness levels will not continue to improve at the same rate as athletes become fitter. Variation Principle This principle has several meanings. After your athletes have trained hard for several days, they should train lightly to give their bodies a chance to recover. Over the course of the year use training cycles (periodization) to vary the intensity and volume of training to help your athletes achieve peak levels of fitness for competition. This principle also means that you should change the exercises or activities regularly so that you do not overstress a part of the body. Of course changing activities also maintains athletes’ interest in training. Perhaps you’re thinking that the specificity principle and variation principle seem to be incompatible. The specificity principle states that the more specific the training to the demands of the sport, the better; and the variation principle seemingly asserts the opposite-train by using a variety of activities. The incompatibility is resolved by the degree to which each principle is followed. More specific training is better, but it can become exceedingly boring. Thus some variety that involves the same muscle groups is a useful change. Reversibility Principle We all know the following adage: Use it or lose it. When athletes stop training, their hard-won fitness gains disappear, usually faster than they were gained. The actual rate of decline depends on the length of the training period before detraining, the specific muscle group, and other factors. A person confined to complete bed rest is estimated to lose cardiovascular fitness at the rate of 10 percent a week. Smart coaches and athletes today recognize that maintaining a moderately high level of fitness year-round is easier than detraining at the end of the season and then retraining at the beginning of the next. Individual Differences Principle Every athlete is different and responds differently to the same training activities. As discussed in chapter 5, the value of training depends in part on the athlete’s maturation. Before puberty, training is less effective than after puberty. Other factors that affect how athletes respond to training include their pretraining condition; genetic predisposition; gender and race; diet and sleep; environmental factors such as heat, cold, and humidity; and of course motivation. As discussed previously, it’s essential to individualize training as much as possible.