Latest version (Dec 9, 2015)

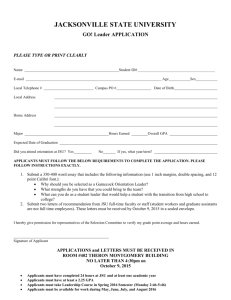

advertisement