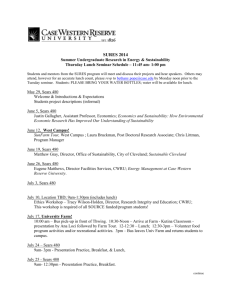

University of Colorado-Boulder

Leeds School of Business

FNCE 4826

Seminar in Corporate Governance

Spring 2015

KOBL 340

W 3:30 pm - 6:15 pm

Sanjai Bhagat

Office: KOBL S431

sanjai.bhagat@colorado.edu

Office Hours: TH 1 pm – 3pm

I. Course Objective

Corporate governance consists of the set of corporate policies that ensures outside investors a

fair return on their investment. The objective of the course is to provide the student with a stateof-the-art understanding of corporate governance as it relates to

Corporate control

Corporate performance

Board structure and effectiveness

Executive and board compensation

Entrepreneurship and private equity

Corporate social responsibility

II. Course Materials and Prerequisite

Course materials consist of scholarly journal articles and working papers. These and

lecture notes/overheads and class announcements can be accessed from my home-page:

http://leeds-faculty.colorado.edu/bhagat

The recommended textbook for this course is Corporate Governance Matters by David

Larcker and Brian Tayan, FT Press, 2011.

Articles from the Wall Street Journal will be used to motivate some of the class discussion.

www.wsj.com/studentoffer www.wsj.com/quarter

This is a Finance elective. FNCE 3010 is a prerequisite.

III. Course Outline and Readings

A. Introduction

Corporate Governance Matters Chapter 1. IntroductionAgencyTheoryApplication

IntroductionCorporateGovernance

B. Corporate Control: Mergers and Takeovers

Corporate Governance Matters Chapter 11.

Andrade, M. Mitchell, and E. Stafford. "New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers." Journal of

Economic Perspectives (2001): 103-120. NewEvidenceMergers.ppt

target-gain-goodfile.doc

S. B. Moeller, F. P. Schlingemann, R. M. Stulz, “Firm Size and the Gains From Acquisitions,” Journal of

Financial Economics 73, 2004, 201-228.

J. Harford, M. Humphery-Jenner, R. Powell. “The sources of value destruction in acquisitions by

entrenched managers,” Journal of Financial Economics, Volume 106, November 2012, Pages 247–26.

U. Malmendier and G. Tate, “Who Makes Acquisitions? CEO Overconfidence and the Market’s

Reaction,” Journal of Financial Economics 89, 20-43, 2008. CEO-Overconfidence.ppt

M. Zhao and K. Lehn, “CEO Turnover After Acquisitions: Do Bad Bidders Get Fired?” 2006, Journal of

Finance 61, 1759-1812.

Spinoffs and Corporate Refocusing

P. G. Berger and E. Ofek, “Causes and Effects of Corporate Refocusing Programs,” Review of Financial

Studies 12, 1999, 311-346. Spinoffs.ppt

S. Krishnaswami and V. Subramaniam, “Information asymmetry, Valuation, and the Corporate Spin-off

Decision,” 1999, Journal of Financial Economics 53, 1999, 73-112.

C. Shareholder Voting and Activism

J.A. Brickley, R.C. Lease and C.W. Smith, Jr., "Ownership Structure and Voting on Antitakeover

Amendments," Journal of Financial Economics 20, 1988, 267-292. Antitakeover.ppt

S. Bhagat and R.H. Jefferis, "Voting Power in the Proxy Process: The Case of Antitakeover Charter

Amendments," Journal of Financial Economics 30, 1991, 193-226.

L. Bebchuk, A. Brav and W. Jiang, “The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism,” Harvard

University working paper, 2013.

A. Brav, W. Jiang, F. Partnoy, and R. Thomas, “Hedge Fund Activism, Corporate Governance, and Firm

Performance,” 2010, Duke University working paper.

Paul Gompers*, Steven N. Kaplan and Vladimir Mukharlyamov, “What Do Private Equity Firms Do?”

2014, Harvard University working paper.

2

Steven Davis, et al, “Private Equity, Jobs, and Productivity,” 2014, University of Chicago working paper.

Corporate Governance Matters Chapter 12.

D. Corporate Board Structure

Corporate Governance Matters Chapters 3, 4, and 5.

Gompers, P. A., J. L. Ishii, and A. Metrick, 2003, Corporate governance and equity prices, Quarterly

Journal of Economics 118(1), 107-155.

S. Bhagat and B. Bolton, “Corporate Governance and Firm Performance,” Journal of Corporate Finance

14, 257-273, 2008. Corporate Governance – Performance.ppt

S. Bhagat and B. Bolton "Director Ownership, Governance and Performance," Journal of Financial &

Quantitative Analysis, 2013, Sox-GovernancePerformance.

S. Bhagat , B. Bolton, and R. Romano, “The Promise and Pitfalls of Corporate Governance Indices,”

Columbia Law Review, v108 n8, pp 1803-1882, 2008

E. Management and Board Compensation

Corporate Governance Matters Chapter 8.

S. Bhagat and B. Bolton, “Financial Crisis And Bank Executive Incentive Compensation,” Journal of

Corporate Finance, 2014. BankCompensationCapitalReform

S. Bhagat , B. Bolton, and R. Romano, “Getting Incentives Right: Is Deferred Bank Executive Compensation

Sufficient?” Yale Journal on Regulation, 2014.

F. Corporate Social Responsibility

Kitzmueller, Markus and Jay Shimshack. "Economic Perspectives On Corporate Social Responsibility,"

Journal of Economic Literature, 2012, v 50(1), 51-84.

Simons, Robert, “The Business of Business Schools: Restoring a Focus on Competing to Win,” Harvard

Business School, Capitalism and Society: Vol. 8: Iss. 1 , Article 2., 2013.

3

IV.

Course Policies

Course Schedule

January 14

January 21

January 28

February 4

February 11

February 18

February 25

March 4

March 11

March 18

March 25

April 1

April 8

April 15

April 22

April 29

May 6

Introduction

Corporate Control

Corporate Control

Proposal due

Shareholder Voting and Activism

Corporate Board Structure

Corporate Board Structure

Corporate Board Structure

Management and Board Compensation

Management and Board Compensation

Paper draft due

Governance and Venture Financing

Spring Break

Governance and Venture Financing

Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility

Student Presentations

Student Presentations

Final Exam (8:30 am – 10:00 am)

Grading

The grade breakdown is as follows:

Item

A.

Class participation and attendance

B.

Term Paper (proposal, due: January 28)

C.

Term Paper (draft, due: March 11)

D.

Term Paper (write-up, due: April 8)

E.

Term Paper (presentation)

F.

Final Exam (May 6)

Paper due

Weight

10%

5%

15%

25%

15%

30%

A.

Class participation is critical to the success of this course. Student questions and comments are

expected and welcome. Attendance will be taken at random (unannounced). Students are requested to

place their name-cards in front of their desk at all times during class.

The class will be conducted in a professional manner: Students and the instructor are expected to

be prepared for each class, and behave professionally in the class.

B.

Proposals for the term paper are due on January 28, 2015, before the start of class. The proposal

should answer the following two questions:

What will the paper be about?

Why is this topic interesting and important?

You should also include a list of at least four academic papers or book chapters that you intend to read

as background for your paper. The proposal should be no more than a page.

C, D, E. The term paper draft is due on March 11, 2015, before the start of class. The term paper draft

4

should be at least ten pages long, and include the following:

What is the paper about?

Why is this interesting and important to study/read?

A critical survey of the literature.

Outline of the original analysis that would be of interest to somebody in the real world: an

investment banker, venture capitalist, or entrepreneur.

References that includes at least four academic papers or book chapters.

The term paper is due on April 8, 2015.

Student presentations are scheduled for April 15, 22 and 29, 2015. The paper can be on any topic that

will be covered in the course. The paper should include a critical survey of the literature and some

original analysis that would be of interest to somebody in the real world: Chairman of Board,

CEO, CFO, policy makers and their staffs, compensation consultants, investment bankers, or

private equity investors. The paper (including exhibits) should be between 20 and 25, double-spaced

pages (twelve-point font, one-inch margin all-around).

On your paper please note the following:

On my honor, as a University of Colorado at Boulder student, I have neither given nor received

unauthorized assistance on this paper.

A Note on Academic Honesty & Plagiarism: The development of the Internet has provided students with

historically unparalleled opportunities for conducting research swiftly and comprehensively. The

availability of these materials does not, however, release the student from appropriately citing sources

where appropriate; or applying standard rules associated with avoiding plagiarism. Please see

http://www.colorado.edu/academics/honorcode

Grade distribution:

http://leeds.colorado.edu/asset/undergraduate/gradingpolicy.pdf

Also, please review

http://www.colorado.edu/policies/fac_relig.html,

http://www.colorado.edu/policies/classbehavior.html,

http://www.Colorado.EDU/disabilityservices,

and http://www.colorado.edu/policies/discrimination.html.

5

Guidance to Faculty Regarding Grade Distributions

In May 2011, the faculty of the Leeds School voted to establish the “grading guidelines” shared below.

With this vote, the faculty returns to its preͲ2009 approach of grading guidelines.

These guidelines embody the faculty’s consensus about competition and fairness within, and across,

classroom experiences at Leeds. In its discussions and preparations, the faculty relied heavily on

norms and customs at topͲtier business schools throughout the U.S.

The following matrix provides guidance on grade distributions either at the course level or aggregated

across multiple, simultaneous sections.

Course Level

1000 and 2000

Maximum Average Course Grade

2.8

3000

3.0

4000

3.2

6

Recommended Distribution

Not more than 15% AͲ or above

Not more than 65% BͲ or above

At least 35% C+ or below

Not more than 25% AͲ or above

Not more than 75% BͲ or above

At least 25% C+ or below

Not more than 35% AͲ or above

Not more than 85% BͲ or above

At least 15% C+ or below

Guidelines for the Term Paper

Suggested order for the sections:

Cover Page

Paper Title, Student Names, Course, Date

Executive Summary

No more than one page. The most important part of your paper! Briefly explain what the paper is about, why this is

an interesting and important topic, and your main findings/conclusions. Consider an entrepreneur, investment banker,

investor, or venture capitalist as your primary reader of this page.

Introduction

What is the paper about?

Motivation: Why is this interesting and important to study/read?

Overview of the paper.

(Main Body)

Please consider using sub-sections to better organize your paper, and improve its readability.

Please check the transition between paragraphs.

(Footnotes on same page.)

Summary and Conclusions

Exhibits (Tables, Graphs, etc.)

Captions and legends in the exhibits should make them self-explanatory. Cite data sources.

References

____________________________________________________________________

Check for grammar and spelling.

All arguments/assertions should be supported using:

logical constructs, and/or

theoretical considerations (cite references), and/or

previous empirical evidence (cite references).

Paper should be revised by you at least four times over a period no less than a week.

7

F.

The exam will consist of essay-type questions, and will be closed-book, closed-notes, and inclass. The exam will be based on study questions that will be handed out during the semester. The exam

will be graded anonymously in the sense that students will not write their names on the exam and at the

time I grade the exam I will not know whose exam it is.

Readings

You are advised to read the “critical portions” of the assigned readings for a particular class

before that class. The critical portions of a reading include the abstract, introduction,

summary/conclusions of the paper. You might wish to read the main body of the paper after we

have discussed it in class.

V. Additional Readings (Particularly helpful if your term paper is on one of the following

topics)

B. Corporate Control

Mergers and Takeovers

1. S. Bhagat, A. Shleifer, and R.W. Vishny, "Hostile Takeovers in the 1980s: The Return to Corporate

Specialization," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1990, 1-84. target-gain-goodfile.doc

2. G. Andrade, M. Mitchell, and E. Stafford. "New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers." Journal of

Economic Perspectives (2001): 103-120. NewEvidenceMergers.ppt

3. E.H. Kim and V. Singal, "Mergers and Market Power: Evidence from the Airline Industry," American

Economic Review 83, 1993, 549-569.

4. S. Bhagat, M. Dong, D. Hirshleifer and R. Noah, "Do Tender Offers Create Value?" Journal of

Financial Economics, 2005, V76 N1, 3-60. b-hirshleifer.ppt

5. S. B. Moeller, F. P. Schlingemann, R. M. Stulz, “Firm Size and the Gains From Acquisitions,”

Journal of Financial Economics 73, 2004, 201-228.

6. S.B. Moeller, F. P. Schlingemann, and R.M. Stulz, “Wealth Destruction on a Massive scale? A Study

of Acquiring-Firm returns in the Recent Merger Wave, Journal of Finance 60, 2005, 757-782.

7. J. Harford, M. Humphery-Jenner, R. Powell. “The sources of value destruction in acquisitions by

entrenched managers,” Journal of Financial Economics, Volume 106, November 2012, Pages 247–

26.

8. U. Malmendier and G. Tate, “Who Makes Acquisitions? CEO Overconfidence and the Market’s

Reaction,” Journal of Financial Economics 89, 20-43, 2008.

9. M. Zhao and K. Lehn, “CEO Turnover After Acquisitions: Do Bad Bidders Get Fired?” 2006,

8

Journal of Finance 61, 1759-1812.

10. S. Bhagat, S. Malhotra and P.C. Zhu, “Emerging country cross-border acquisitions: Characteristics,

acquirer returns and cross-sectional determinants,” Emerging Markets Review, Volume 12, September

2011, Pages 250-27.

11. I. Erel, R.C. Liao, and M.S. Weisbach, “Determinants of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions,”

Journal of Finance 67, 2012, pages 1045–1082.

Spinoffs and Corporate Refocusing

1. B. E. Eckbo and K.S. Thorburn, Corporate Restructuring, Foundations and Trends in Finance, 2013.

2. P. G. Berger and E. Ofek, “Causes and Effects of Corporate Refocusing Programs,” Review of

Financial Studies 12, 1999, 311-346. Spinoffs.ppt

3. L Daley, V. Mehrotra, and R. Sivakumar, “Corporate Focus and Value Creation: Evidence fron

Spinoffs,” 1997, Journal of Financial Economics 45, 257-281.

4. S. Krishnaswami and V. Subramaniam, “Information asymmetry, Valuation, and the Corporate Spinoff Decision,” 1999, Journal of Financial Economics 53, 1999, 73-112.

5. S. Ahn and D.J. Denis, “Internal Capital Markets and Investment Policy: Evidence From Corporate

Spinoffs,” Journal of Financial Economics 71, 2004, 489-516.

6. T.R. Burch and V. Nanda, “Divisional Diversity and the Conglomerate Discount: Evidence From

Spinoffs,” Journal of Financial Economics 70, 2003, 69-98.

C. Shareholder Voting and Activism

1. J.A. Brickley, R.C. Lease and C.W. Smith, Jr., "Ownership Structure and Voting on Antitakeover

Amendments," Journal of Financial Economics 20, 1988, 267-292. Antitakeover.ppt

2. S. Bhagat and R.H. Jefferis, "Voting Power in the Proxy Process: The Case of Antitakeover Charter

Amendments," Journal of Financial Economics 30, 1991, 193-226.

3. D. DelGuercio and J. Hawkins, “The Motivation and Impact of Pension Fund Activism,” Journal of

Financial Economics 52, 1999, 293-340.

4. L. Bebchuk, A. Brav and W. Jiang, “The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism,” Harvard

University working paper, 2013.

5. L.A. Bebchuk and E. Kamar, “Bundling and Entrenchment,” Harvard Law Review, May 2010.

6. A. Brav, W. Jiang, F. Partnoy, and R. Thomas, “Hedge Fund Activism” 2010, Duke University

working paper.

7. S. Bhagat and R. Romano, “Empirical Studies of Corporate Law,” in Handbook of Law & Economics, 2007.

9

CorporateLaw.ppt

D. Corporate Board Structure

1. S. Bhagat and B. Black, “The Non-Correlation Between Board Independence and Long-Term Firm

Performance” Journal of Corporation Law, 2002, Volume 27, Number 2. b-black.ppt

2. S. Bhagat and R.H. Jefferis, The Econometrics of Corporate Governance Studies, 2002, MIT Press.

3. S. Bhagat and B. Bolton, “Corporate Governance and Firm Performance,” Journal of Corporate

Finance 14, 257-273, 2008. Corporate Governance – Performance.ppt

4. S. Bhagat and B. Bolton "Director Ownership, Governance and Performance," Journal of Financial

& Quantitative Analysis, 2013, Sox-GovernancePerformance.

5. S. Bhagat , B. Bolton, and R. Romano, “The Promise and Pitfalls of Corporate Governance Indices,”

Columbia Law Review, v108 n8, pp 1803-1882, 2008

6. S. Bhagat and H. Tookes, “Voluntary and Mandatory Skin in the Game: Understanding Outside

Director's Stock Holdings,” European Journal of Finance, 2011.

E. Management and Board Compensation

M.C. Jensen and K.J. Murphy, "Performance Pay and Top-Management Incentives," Journal of Political

Economy 98, 1990, 225-264.

B. J. Hall and J. B. Liebman, “Are CEOs Really Paid Like Bureaucrats?” 1998, Quarterly Journal of

Economics 108, 653-691. Hall-Liebman.ppt

C.S. Armstrong, D. F. Larcker, G. Ormazabal, and D. J. Taylor, “The Relation Between Equity

Incentives and Misreporting: The Role of Risk-taking Incentives,” Journal of Financial Economics

109, 327-350, 2013.

Armstrong, C. S., A. Jagolinzer and D. Larcker, “Chief Executive Officer Equity Incentives and Accounting

Irregularities”, Journal of Accounting Research 48, 225-271, 2010.

S. Bhagat and B. Bolton, “Financial Crisis And Bank Executive Incentive Compensation,” Journal of

Corporate Finance, 2014.

S. Bhagat , B. Bolton, and R. Romano, “Getting Incentives Right: Is Deferred Bank Executive Compensation

Sufficient?” Yale Journal on Regulation, 2014. ReformingExecComp

Anat R. Admati, Peter M. DeMarzo, Martin F. Hellwig, Paul C. Pfleiderer, “Fallacies, Irrelevant Facts,

and Myths in the Discussion of Capital Regulation: Why Bank Equity is Not Expensive,” Stanford

University working paper, September 2011.

10

F. Governance and Venture Financing

1. S.N. Kaplan and Per Stromberg. "Financial Contracting Theory Meets The Real World: An

Empirical Analysis Of Venture Capital Contracts," Review of Economic Studies, 2003,

v70(2,Apr), 281-315.

2. S. N. Kaplan, B. A. Sensoy, and P. Stromberg, “Should Investors Bet on the Jockey or the

Horse? Evidence from the Evolution of Firms from Early Business Plans to Public

Companies,” Journal of Finance 64, 2009, 75-115.

3. O. Bengtsson and B. A. Sensoy, “Changing the Nexus: The Evolution and Renegotiation of

Venture Capital Contracts,” Ohio State University working paper, 2009.

4.

O. Bengtsson and B. A. Sensoy, “Investor Abilities and Financial Contracting: Evidence

from Venture Capital,” Ohio State University working paper, 2009.

5. O. Bengtsson and S.A.Ravid, “The Geography of Venture Capital Contracts,” Ohio State

University working paper, 2009.

6. H. Chen, P. Gompers, A. Kovner, and J. Lerner, “Buy Local? The Geography of Successful

Venture Capital Expansion,” Harvard University working paper, 2009.

7. Brian Broughmana and Jesse Fried, “Renegotiation of cash flow rights in the sale of VCbacked firms,” Journal of Financial Economics 95, Issue 3, March 2010, Pages 384-399.

G. Corporate Social Responsibility

Kitzmueller, Markus and Jay Shimshack. "Economic Perspectives On Corporate Social Responsibility,"

Journal of Economic Literature, 2012, v50(1), 51-84.

Simons, Robert, “The Business of Business Schools: Restoring a Focus on Competing to Win,” Harvard

Business School, 2013.

Dhaliwal, Dan S., Oliver Zhen Li, Albert Tsang and Yong George Yang. "Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure

And The Cost Of Equity Capital: The Initiation Of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting," Accounting

Review, 2011, v86(1), 59-100.

Dravenstott, John and Natalie Chieffe. "Corporate Social Responsibility: Should I Invest For It Or Against

It?," Journal of Investing, 2011, v20(3), 108-117.

El Ghoul, Sadok, Omrane Guedhami, Chuck C.Y. Kwok and Dev R. Mishra. "Does Corporate Social

Responsibility Affect The Cost Of Capital?," Journal of Banking & Finance, 2011, v35(9), 2388-2406.

Goss, Allen and Gordon S. Roberts. "The Impact Of Corporate Social Responsibility On The Cost Of Bank

Loans," Journal of Banking & Finance, 2011, v35(7), 1794-1810.

Becchetti, Leonardo and Rocco Ciciretti. " Corporate Social Responsibility And Stock Market Performance,”

Applied Financial Economics, 2009, v19(16), 1283-1293

Jensen, Michael C., Putting Integrity into Finance: A Positive Approach, 2011, Harvard NOM Working

11

Paper No. 06-06; Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=876312

J.M. Karpoff, D.S. Lee and G.S. Martin, “The Cost of Cooking the Books,” Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis, 43 (September 2008), 581-612.

J.M. Karpoff, D.S. Lee and G.S. Martin , The consequences to managers for financial misrepresentation,

Journal of Financial Economics,Volume 88, Issue 2, May 2008, Pages 193-215

Glaeser, Edward L., The Governance of Not-for-Profit Firms (April 2002). Harvard Institute of

Economic Research Paper No. 1954. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=313203 or

http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.313203

H. Private Equity

1. S. N. Kaplan and P. Stromberg, “Leveraged Buyouts and Private Equity, NBER paper, 2008.

http://www.privateequityatwork.com/

2. Steven J. Davis , John Haltiwanger , Ron S. Jarmin , Josh Lerner and Javier Miranda, “Private Equity and

Employment,” US Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies Paper No. CES-WP-08-07R, 2014. Private

Equity

3. Paul Gompers, Steven N. Kaplan and Vladimir Mukharlyamov, “What Do Private Equity Firms Do?”

2014, Harvard University working paper.

4. Paglia, John and Harjoto, Maretno Agus, The Effects of Private Equity and Venture Capital on Sales and

Employment Growth in Small and Medium Sized Businesses (June 5, 2014). Journal of Banking and Finance,

Vol. 47, pp. 177-197, 2014.

5. J. Haltiwanger, R. Jarmin, J. Miranda, “Who Creates Jobs?” Review of Economics and

Statistics 95, May 2013, 347-361.

I. Financial Crisis

K. French et al, The Squam Lake Report, 2010, Princeton University Press.

A. Purnanandam, "Originate-to-Distribute Model and the Sub-prime Mortgage Crisis"

Review of Financial Studies, 2011, 24, 1881-1915.

Bhattacharyya, Sugato and Purnanandam, Amiyatosh K., Risk-Taking by Banks: What Did We

Know and When Did We Know It? (November 18, 2011).

Taylor D.Nadauld, ShaneM.Sherlund,The impact of securitization on the expansion of subprime

credit, Journal of Financial Economics 107, 2013, 454-476.

12

Study Questions – FNCE 4825 (March 31, 2015)

1. (a) What is corporate governance?

(b) Why would a private high-tech start-up care about corporate governance?

[IntroductionCorporateGovernance.ppt]

2. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of common stock residual claims.

[IntroductionAgencyTheoryApplication]

3. Discuss the sources of conflict of interest between managers and shareholders. Discuss the

mechanisms to control this conflict of interest. [IntroductionAgencyTheoryApplication]

3. (a) What does it mean to say that a market is efficient?

(b) A certain investment advisor claims that the clients she has advised in the past have done “better than

the market” because in the past five years the portfolio she had recommended beat the market by the

following: 1.5%, 2.5%, 0.5%, -0.5%, -1.25%. Evaluate her claim. [CAPM-EMH.ppt]

4. a) Target shareholders generally receive substantial positive abnormal returns during takeovers. What

are the hypothesized sources of these abnormal returns? [target-gain.doc] [NewEvidenceMergers.ppt]

4. b) What is the empirical evidence on returns to bidders in takeovers? Discuss potential problems in

the traditional ways of measuring returns to bidders in takeovers. [b-hirshleifer.ppt]

[NewEvidenceMergers.ppt]

5. (a) What is Roll’s Hubris Hypothesis of corporate acquisitions? Explain. Discuss Malmendier-Tate’s

(2008) evidence on this. How do they identify hubristic CEOs?

(b) Do bad bidders get fired? [CEO-Overconfidence.ppt]

6. (a) During the last decade corporations are said to be refocusing. What is meant by “corporate

refocusing”? Discuss why corporations might be refocusing; please consider the evidence in

Krishnaswami and Subramaniam (1999), Ahn and Denis (2004) and Daley, et al (1997).

(b) What might be the role of market disciplinary forces, and internal governance mechanisms in

spurring corporate refocusing as discussed in Berger and Ofek (1999). [Spinoffs.ppt]

7. (a) What are antitakeover amendments?

(b) Why might antitakeover amendments be in shareholders’ interest?

(c) Why might antitakeover amendments not be in shareholders’ interest?

(d) What is the empirical evidence on when managers are more likely to propose antitakeover

amendments? [Antitakeover.ppt]

8 (a) What are the long term effects of hedge fund activism?

(b) Why might hedge fund activism be different than institutional investor activism? [Antitakeover.ppt]

Bebchuk-Brav-Jiang (2013)

9. Recently academics (GIM, Bhagat and Bolton (2008)), and industry advisors to institutional investors

(The Corporate Library) have suggested ways to measure corporate governance for companies.

13

(a) Describe the three measures of corporate governance.

(b) What are the pros and cons of these three measures of corporate governance?

(c) What is the empirical evidence on the effectiveness of these three measures of corporate governance?

[Corporate Governance-Performance.ppt]

10. What is the impact of the following corporate governance measures on corporate performance,

disciplinary management turnover, and M&A activity before and after the passage of the SarbanesOxley Act?

a) GIM index; (b) director ownership; (c) board independence. [Sox- Governance-Performance.ppt]

11. Bebchuk, Cohen and Spamann (2010) study the compensation structure of the top executives in

Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers and conclude, “…given the structure of executives’ payoffs, the

possibility that risk-taking decisions were influenced by incentives should not be dismissed but rather

taken seriously.”

Fahlenbrach and Stulz (2011) focus on the large losses experienced by CEOs of financial institutions via

the declines in the value of their ownership in their company’s stock and stock option during the crisis

and conclude, “Bank CEO incentives cannot be blamed for the credit crisis or for the performance of

banks during that crisis.”

(a) How might you differentiate between these two points of view?

(b) What recommendations might you make regarding executive compensation, and capital structure of

large financial institutions? Why?

[BankCompensationCapitalReform]

_____________________________

Please note: The Final Exam will consist of four questions drawn from the above.

You will be asked to answer three of these four questions.

It is expected that the answer to each question would take about 30 minutes.

14

Test the Medical Skills of Aspiring

Doctors

WALL STREET JOURNAL April 26, 2015 5:08 p.m. ET

The new sections of the MCAT will prepare our young doctors for their medical careers (“MedicalSchool Test Gets a Revamp,” U.S. News, April 16). The “power, privilege and prestige” section will

enable them to understand government, insurance companies, administrators and the board examination

industry. “Class consciousness” questions will help them accept their large debt load and inability to

purchase a home. They will be able to tolerate that their salaries are less than those of their handlers and

regulators.

I am glad that there are dedicated, intelligent, hardworking students to take care of us when we are sick.

They have no advocate and are at the mercy of government and career academicians. Let’s stop making

them jump through hoops to become doctors. Don’t waste their time on political correctness. I hope the

doctor operating on me doesn’t spend 25% of his time reading sociology textbooks.

Thomas F. O’Malley Jr., M.D.

Huntingdon Valley, Pa.

15

WALL STREET JOURNAL, PAGE A1, MARCH 31, 2015

MARKETS

Regulators Intensify Scrutiny of Bank

Boards

Fed and others hold more frequent meetings with directors

By

VICTORIA MCGRANE and

JON HILSENRATH

Updated March 30, 2015 11:48 p.m. ET

44 COMMENTS

WASHINGTON—U.S. regulators are zeroing in on Wall Street boardrooms as part of the government’s

intensified scrutiny of the banking system, shifting from light-touch oversight of bank directors to

regular questioning.

The Federal Reserve and other bank regulators are holding frequent, in some cases monthly, meetings

with individual directors at the nation’s biggest banks, demanding detailed minutes and other

documentation of board meetings and singling out boards in internal regulatory critiques of bank

operations and oversight.

In some instances, Fed supervisors meet more often with directors than the directors meet formally as a

full board. Boards at small banks are also getting new attention from regulators. This account is based

on interviews with government, industry and other people familiar with the efforts as well as public

statements.

The change has Washington overseeing the overseers, as regulators home in on whether directors are

adequately challenging management and monitoring risks in the banking system.

They are reviewing information directors get from bank management, asking about succession planning

and inquiring about how directors gauge the potential downsides of certain transactions, among other

things, according to industry and government officials.

Advertisement

16

“We have the independent directors’ attention,” Comptroller of the Currency Thomas Curry said in an

interview. Examiners from his office, which regulates national banks including units of large firms

like Bank of America Corp. and Citigroup Inc., meet informally with lead directors and audit and risk

committees several times a year.

Within the last month, Fed supervisors have had numerous conversations with directors about the results

of the annual “stress tests” which determine whether the bank can return capital to shareholders.

The Fed and the OCC say the board oversight helps make the financial system safer, but directors

complain they are being asked to take on too much responsibility.

“A director isn’t management,” said an independent board member of a large Fed-supervised U.S. bank.

17

ENLARGE

18

The threat of being held accountable for failing to properly supervise management is “creating a ton of

tension” for directors, this person said. This person also complained about the board being “written up”

regularly in confidential supervisory reports on the bank.

Interviews with people familiar with the situation said interaction varies depending on the bank.

At Goldman Sachs Group Inc., the bank’s lead independent director meets monthly with its primary Fed

supervisor. Morgan Stanley, under the direction of Chief Executive James Gorman, allows Fed

supervisors to sit in on a portion of each board meeting, where they can listen and ask questions.

The lead director at Bank of America holds monthly calls with supervisors at the Fed and OCC while

board committee leaders meet in person with supervisors several times a year. At J.P. Morgan Chase &

Co., Fed supervisors attend some board committee meetings and directors meet regularly with

supervisors outside of the formal board meetings.

A bank executive referred to the Fed’s increased focus as “Occupy Board Meetings,” saying supervisors

had become a regular presence at director gatherings.

In at least one instance, the Fed is proposing to dictate the board makeup of a company under its

purview. The Fed has told General Electric Co.’s GE Capital unit, which recently came under Fed

supervision because of its designation as a “systemically important financial institution,” to add two new

members to its seven-member board who are independent of the financial-services business and the

parent company’s board.

The GE board, in a Feb. 2 letter to the Fed, called the requirement “unprecedented” and said it would

“actually undermine our independent oversight of GE Capital’s enterprise risks by disrupting the

cohesive decision-making that is necessary for the effective governance of a complex wholly-owned

subsidiary like GE Capital.” Among those who signed the letter was Mary Schapiro, former Securities

and Exchange Commission chairman, who joined GE’s board as an independent director in 2013. The

letter is on file at the Fed.

Outside groups have also raised alarms about the Fed’s proposal, including two investment managers

with positions in GE stock. The Fed’s proposed director requirement “blurs the lines of accountability

that are central to a strong, effective corporate governance,” John N. Iannuccillo, a vice president at

Dodge & Cox, one of the GE investors, wrote in a letter to the Fed.

19

While Fed and OCC supervisors have long interacted with bank boards, including meeting to discuss the

confidential ratings assigned to each bank, directors and other industry officials say directors have begun

facing a new level of scrutiny over the past two years.

“There is more supervisory contact with the boards than ever before,” said Eugene Ludwig, chief

executive officer of advisory firm Promontory Financial Group and a former comptroller of the

currency.

After years of pushing banks to boost their capital cushions, regulators are now focusing on corporate

governance and the role of directors to ensure banks have the right culture and controls to prevent

excessive risk taking. The 2008 crisis showed regulators that some boards—and senior management—

didn’t understand the risks firms were taking or didn’t exercise appropriate oversight.

In some cases, board members weren’t experienced enough or were too closely tied to the bank to

perform their duties. Studies since the financial crisis—for example, the International Monetary Fund’s

October 2014 Global Financial Stability report— have shown banks with independent directors are less

likely to take on risk, while boards chaired by the bank’s CEOs take more risk.

Directors at small banks are also being pressed, including on how much they understand the kinds of

loans banks are making and the associated risks, said Camden Fine,president and CEO of the

Independent Community Bankers of America.

Last year, the OCC ignited a firestorm when it proposed new requirements for directors at the biggest

banks, including that they “ensure” senior management addressed risks. In comment letters and

meetings with OCC officials, directors and banks said such language pushed directors to take on

managerial duties beyond their traditional role as overseers.

“We are concerned that the language of the proposal may have the unintended consequence of

establishing new, material obligations on boards that are impractical to meet and that could give rise to

new director liability claims and deter interest in board service,” Wells Fargo & Co. wrote in a March

2014 letter.

20

The OCC revised sections of the final version to “avoid imposing managerial responsibilities on board

members” and said they never intended to change the board’s fundamental role.

Washington’s laser focus on boards has raised concerns banks will have trouble recruiting and retaining

qualified directors, stoked by lawsuits brought by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. against former

directors of banks that failed during the crisis, industry officials say.

About 25% of the 80 banks that responded to an American Association of Bank Directors survey last

year reported they had either had a director resign, decline to join the board or refuse to serve on the

board’s loan committee “out of fear of personal liability.”

David Baris, who heads the group and is a partner at law firm BuckleySandler LLP, said there are

“simply people who won’t serve as directors who would otherwise be qualified to serve because of that

fear” of personal liability. Some lawyers are advising would-be directors to just say no. Oliver Ireland, a

partner at Washington law firm Morrison & Foerster, said on a panel in November he recommends

against anyone joining a bank board. “I think the downside risks exceed the benefits that the individual

would achieve,” he said.

Regulators defend the new approach, saying board engagement benefits both sides by giving a clearer

view of supervisors’ expectations and the firms’ most pressing regulatory issues. Some directors have

told regulators they welcome the increased interaction with supervisors, with at least one director saying

regulators should be tougher on board members who don’t do their jobs.

Officials say directors are also reaching out on their own and traveling to Washington more frequently to

meet with senior Fed officials.

Still, Fed Gov. Daniel Tarullo acknowledged in a speech last summer that regulators are sometimes

guilty of placing too many requirements on boards and would be better off advising boards to spend

most of their time overseeing risk management systems and controls.

“We should probably be somewhat more selective in creating the regulatory checklist for board

compliance and regular consideration,” he said.

21

Sarah Dahlgren, head of bank supervision at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, said in a speech

last fall that her team had seen progress in the program of “enhanced engagement” with boards and

senior management she launched three years earlier when she took over the division. Boards seem more

comfortable with supervisors, she observed, with directors no longer tending to bring a compliance or

regulatory-relations officer along to meetings, as many did at the start.

“While the level of engagement varies across firms, in general, we are seeing boards being more active

in asking questions, providing oversight of management and engaging with supervisors. We, in turn,

have deeper insight into decision-making dynamics at the board and c-suite level, including the how and

why of decision making on key strategic issues,” she said.

—Ted Mann contributed to this article.

Corrections & Amplifications:

John N. Iannuccillo, a vice president at Dodge & Cox, one of the GE investors, wrote in a letter to the

Fed that the Fed’s proposed director requirement “blurs the lines of accountability that are central to a

strong, effective corporate governance.” An earlier version of this article omitted that he was the source

of the quote.

Write to Victoria McGrane at victoria.mcgrane@wsj.com and Jon Hilsenrath atjon.hilsenrath@wsj.com

22

WALL STREET JOURNAL, MARCH 24, 2015

MEDIA & MARKETING

Vivendi Urged to Bolster Returns to

Investors

Activist fund calls the media group undervalued, faults ‘excessive’ cash

holdings

ENLARGE

Vivendi Chairman Vincent Bolloré has said little about his plans for the future of the media

conglomerate. PHOTO: BLOOMBERG NEWS

By

RUTH BENDER

Updated March 23, 2015 4:34 p.m. ET

0 COMMENTS

PARIS—A U.S. activist fund is raising pressure on Vivendi SA to boost shareholder returns and clarify

its strategy ahead of next month’s annual meeting, highlighting a growing malaise among minority

shareholders over where group Chairman Vincent Bolloré is driving the media conglomerate.

U.S. hedge fund P. Schoenfeld Asset Management on Monday submitted to Vivendi management two

resolutions for the meeting on April 17 demanding Vivendi return a total of €9 billion ($10 billion) in

the form of a special dividend.

“PSAM believes that Vivendi is significantly undervalued due to its excessive cash holdings, inadequate

capital return policy and the uncertainty over Vivendi’s future use of its capital,” the U.S. hedge fund

founded by Peter M. Schoenfeld said in a written statement.

The pressure on Vivendi’s chairman comes as the company stands at a strategic crossroads.

Faced with the challenge of reviving growth, Vivendi has sold off assets that accounted for more than

half of its revenue, including videogames maker Activision Blizzard and telecommunications companies

in France and Morocco. As a result, the once-sprawling conglomerate has slimmed down to two media

businesses: California-based Universal Music Group and French pay-television provider Canal

Plus Group.

MORE

Heard on the Street: Vivendi’s Playlist Is Only on Hold (March 10)

23

Vivendi Awaits Its Chairman’s Next Move (March 8)

Bolloré Group Raises Stake in Vivendi to 8.2% from 5.2% (March 2)

At stake is what Vivendi will do with the roughly €10 billion it will have on its balance sheet after

closing outstanding asset sales and planned returns to shareholders.

“Excess cash on Vivendi’s balance sheet is distorting the potential returns for investors in the company,”

PSAM said. The fund said it submitted a white paper to Vivendi outlining its views on how Vivendi

should use its cash, which it believes should create better value for shareholders. After paying back more

money to shareholders via a special dividend, Vivendi would be left with €5 billion of cash it could use

to expand, the fund said.

Advertisement

In letters to Vivendi, PSAM has made several requests in recent months, seeking higher returns for

shareholders and explanations on how Vivendi intends to use a multibillion-euro cash pile, according to

people familiar with the matter.

In December, PSAM, which owns less than 1% of Vivendi, also recommended Vivendi sell Universal

Music Group.

Vivendi said Monday it opposes the idea of parting with the music business. “The management board

opposes the dismantling of Vivendi and reaffirms its desire to build a Paris-based global industrial

content and media group,” Vivendi said in a written statement.

Vivendi also said that the majority of shareholders it met with recently had expressed satisfaction with

the company’s strategy.

Mr. Bolloré, who owns 8.2% of Vivendi’s capital and took over as chairman last June, has said little

about his strategic goals beyond pledging to create closer ties between the music and TV units and that

he wants Vivendi to be a French version of German media group Bertelsmann.

Vivendi said in February that it would plow €5.7 billion into dividends and share buybacks by mid-2017

on top of the €1.3 billion paid in 2014. Vivendi said Monday that its planned shareholder returns are

“well balanced.”

24

Some analysts have said they expected returns to be higher after Vivendi agreed to sell its remaining

stake in French telecom group Numericable-SFR last month and as Vivendi management had stated that

acquisitions were possible—although only under “strict financial discipline.”

Many also struggled to understand why Vivendi decided to sell its 20% stake in Numericable-SFR at a

price many believed was too low.

Write to Ruth Bender at Ruth.Bender@wsj.com

25

WALL STREET JOURNAL< MARCH 12, 2015

United Technologies May Spin Off

Sikorsky Helicopter Unit

Sikorsky had $7.5 billion of sales last year

26

ENLARGE

Sikorsky, known for its Black Hawk helicopters, is one of the world’s largest helicopter makers but is United

Technologies’ smallest division. PHOTO: ASSOCIATED PRESS

By

DANA MATTIOLI and

DANA CIMILLUCA

Updated March 11, 2015 9:18 p.m. ET

6 COMMENTS

United Technologies Corp. on Wednesday said it will explore strategic alternatives for its Sikorsky

Aircraft business, including a potential spinoff of the helicopter unit.

The review process should conclude before the end of the year, the industrial conglomerate said in a

news release that followed an earlier report on the move by The Wall Street Journal.

United Technologies will discuss its decision to review alternatives for Sikorsky, which had $7.5 billion

of sales last year, during its annual investor and analyst meeting on Thursday.

Sikorsky, best known for its Black Hawk helicopters, is one of the world’s largest helicopter makers. It

manufactures military and commercial helicopters and is the Pentagon’s largest helicopter supplier by

value. Sikorsky also has an aftermarket business that sells parts and maintenance contracts.

The decision would be the latest shake-up for United Technologies, whose chief executive, Louis

Chênevert, abruptly stepped down in November after board members lost confidence in him.

A number of companies have announced plans to break themselves apart or shed divisions in recent

years, amid a push by some investors for greater focus and accountability on the part of executives.

In addition to its helicopter division, United Technologies makes Otis elevators, Pratt & Whitney jet

engines and Carrier air-conditioning units. The Hartford, Conn., conglomerate has a market value of

$106 billion.

United Technologies CEO Greg Hayes told analysts in December that he was going to re-evaluate the

company’s portfolio, but said he had no plans to sell Sikorsky.

“Everybody wants to sell Sikorsky, but the fact is we’re going to take a hard look at the portfolio, and

we’re going to do what’s right,” Mr. Hayes said at the time.

27

Sikorsky, started in 1925 by Igor Sikorsky on New York’s Long Island and later picked up by United

Technologies in an acquisition, is the company’s smallest division by revenue. Last year, it made $219

million in profit after taking a big charge for the renegotiation of a maritime helicopter contract with the

Canadian government.

The unit has come under pressure amid soft military spending and weakness in demand from oil-field

services companies following the steep drop in crude-oil prices. But it has landed several high-profile

new contracts, including the new presidential helicopter program with Lockheed Martin Corp.

In December, Mr. Hayes said he expected 5% growth for the business compounded through the end of

the decade.

J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. is advising United Technologies on the Sikorsky review.

Peter J. Wallison, Hidden in Plain Sight: What Really Caused the World’s Worst Financial

Crisis and Why It Could Happen Again, 2015, Encounter Books.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/book-review-hidden-in-plain-sight-by-peter-j-wallison1424820768?KEYWORDS=mulligan+casey

28

WALL STREET JOURNAL

MARCH 10, 2015

BUSINESS

GM Sets Buyback, Placating Activists

Nation’s largest car maker is latest to feel pressure by hedge funds

critical of management spending

GM Chief Executive Mary Barra agreed to a $5 billion share buyback and spending on dividends amid pressures

from prominent investors, balancing the auto maker’s need to boost spending on new vehicles and maintain its

investment grade rating. PHOTO:BLOOMBERG NEWS

By

VIPAL MONGA and

DAVID BENOIT

Updated March 9, 2015 10:22 p.m. ET

6 COMMENTS

General Motors Co. on Monday became the latest company to return billions of dollars to shareholders

amid tussles with investors over how to better allocate corporate cash.

Facing a potentially contentious fight over a board seat and a larger buyback, the car maker tried to walk

the line between placating big investors and spending more on its future.

GM disclosed a $5 billion stock repurchase, a sum that comes on top of a previously announced

dividend increase, and an additional $9 billion it will spend this year to improve brands including

Cadillac, boost fuel efficiency and develop electric and driverless cars, among other things.

GM’s decision highlights a dilemma facing many companies as activists cement their toehold in

boardrooms: Who is better at determining the appropriate use of cash as corporate balances grow?

Some data suggest activists discourage companies from investing in their businesses, something many

activists would readily admit, citing wasteful spending.

29

ENLARGE

Companies in the S&P 500 targeted by activists between 2003 and 2013 reduced their spending on

plants, equipment and research to 29% of their cash from operations in the five years after activists

bought their shares from a median of 42%, according to an analysis conducted for The Wall Street

Journal by S&P Capital IQ’s Quantamental Research unit.

That compares with the much smaller drop to 25% from 27% for nontargeted companies over the same

period.

Meantime, corporations targeted by activists boosted dividends and stock repurchases to a median of

37% of operating cash flow in the first year after being approached by activists, from 22%. S&P 500

companies that weren’t targeted by activists showed a 10-point increase, to 36%.

“Companies only have a finite amount of cash,” said David Pope, a managing director at S&P Capital

IQ. “If they spend it on shareholder returns, there is less cash to spend on everything else.”

30

GM made its buyback decision after top officials determined its $25 billion in cash was more than

enough to fulfill spending plans and handle uncertainties like the federal investigation into a botched

ignition-switch recall. People familiar with the decision said a buyback already was under consideration

and investor talks sped it up.

‘Companies have a finite amount of cash...’

—David Pope, S&P Capital IQ

“We believe an initial $5 billion share buyback is good for our owners because we cannot earn better

returns by investing that cash in the business at this time,” GM finance chief Chuck Stevens said on a

conference call.

Separately, on Tuesday, some large investors and corporate chiefs are gathering in New York to debate

the social and economic impact of rising shareholder pressure.

The nation’s largest auto maker had come under fire from Harry Wilson, a former architect of GM’s

federal bailout, who wanted an $8 billion buyback and had the backing of four hedge funds in his bid to

get a seat on the company’s board.

“Capital allocation is an underappreciated discipline,” Mr. Wilson said in an interview on Monday.

“When activism works well, one of the things it does is try to create a disciplined framework around this

decision.”

GM had said last month that it would discuss more capital returns later this year.

The company was waiting for clarity around any fine the Justice Department might levy as well as other

litigation that may result from a massive recall due to faulty ignition switches, the people said.

Mr. Wilson and the funds have dropped the request for a board seat in light of the buyback and GM’s

pledge to better explain its spending and goals.

GM stock rose 3.1% to $37.66 in 4 p.m. New York Stock Exchange trading on Monday.

31

Not all investors were excited. James Potkul, a Parsippany, N.J., investment manager who controls about

10,000 GM shares, said the auto maker should instead marshal its cash to protect against uncertainties.

“Are they worried about a downturn? They should be,” he said. “These companies can burn cash pretty

badly when a downturn comes.”

How and when to use capital will be the topic of debate when the group of prominent investors and

executives calling itself Focusing Capital on the Long Term meets in New York.

As a sign of the issue’s weight, U.S. Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew is expected to discuss how public

policy can support the goals of the group’s members, including chief executives such as BlackRock Inc.

’s Laurence Fink , Unilever PLC’s Paul Polman andBarclays PLC Chairman Sir David Walker.

Elliott Management Corp., a New York-based hedge fund, last year started criticizing networkingequipment manufacturer Juniper Networks Inc. for spending $7 billion on acquisitions and nearly $8

billion in research and development while its stock price greatly underperformed the Nasdaq Composite

Index since the company’s 1999 initial public offering.

Last year, after settling with Elliott to change the board, Juniper cut spending and repurchased $2.3

billion of stock. It plans to buy back almost $2 billion more through 2016.

The company paid its first-ever dividend and borrowed money to fund some of the returns.

“The Juniper share repurchase and cost-cutting efforts are the largest contributor to the stock staying

stable,” said Scott Thompson , an analyst with Wedbush Securities.

At the same time, he warned that continued cuts could eventually hamper Juniper’s ability to keep pace

with innovation in the industry.

Some efforts haven’t garnered the same praise. In early 2012, New York investment firm Clinton Group

Inc. took a stake in teen fashion retailer Wet Seal Inc. and began urging a share buyback. By February

2013, the company disclosed it was cutting jobs and expenses and would repurchase $25 million of

stock after appointing four Clinton representatives to its board.

This January, Wet Seal closed two-thirds of its stores and filed for bankruptcy protection.

32

In court documents, executives cited a broader drag on teen retailers as well as missteps that alienated

core customers. People familiar with the bankruptcy say that in hindsight the buyback was a bad

decision.

“If we had rewound and said they hadn’t done the buyback, that would have given them substantially

more flexibility,” said Jeff Van Sinderen, an analyst at B. Riley & Co. “In those situations, $25 million

dollars can go a long way.”

WALL STREET JOURNAL

MARCH 8, 2015

BUSINESS

GM Plans Share Buyback, Averting

Proxy Fight

Investor Harry J. Wilson to drop request to join board in light of

repurchase plan

ENLARGE

Harry J. Wilson has criticized GM’s stock price, cash management and operating

performance. PHOTO: BLOOMBERG NEWS

By

MIKE SPECTOR,

JEFF BENNETT and

JOANN S. LUBLIN

Updated March 8, 2015 11:31 p.m. ET

General Motors Co. as soon as Monday will disclose plans to return billions of dollars to shareholders, a

move that is expected to avoid a potential proxy fight with investor Harry J. Wilson, said people familiar

with the matter.

Mr. Wilson will drop a previous request to join the Detroit auto maker’s board in light of the buyback

plan, the people said. GM plans to repurchase shares over time in an amount less than the $8 billion Mr.

Wilson previously proposed, they said. The size of the buyback and its time frame couldn’t be learned.

Mr. Wilson in February put GM on notice that he intended to nominate himself for a board seat at the

company’s upcoming annual meeting and propose an $8 billion stock buyback. Mr. Wilson has

criticized GM’s stock price, cash management and operating performance.

33

Mr. Wilson and hedge funds backing him have held discussions with GM representatives over the past

several weeks, according to people familiar with the matter, culminating in talks over the weekend that

led both sides to reach a deal that is expected to avoid acrimony, at least in the short term.

GM’s board likely needed to decide soon whether to put Mr. Wilson in its proxy to have ballot materials

ready before the company’s annual meeting, which could take place as soon as June. A rejection, or lack

of some kind of settlement, could have led Mr. Wilson to mount a proxy fight.

Mr. Wilson wants GM to manage its cash better. The auto maker, flush with $25 billion, faces financial

pressures in the months ahead, including a possible hefty fine from the Justice Department over the

company’s failure for more than a decade to recall vehicles equipped with defective ignition switches.

The auto maker has said it plans to weigh returning cash to shareholders as soon as the second half of

this year. The auto maker views its plans as responsive to all shareholders and not solely driven by Mr.

Wilson, said a person familiar with the mater.

Last week, Mr. Wilson beat back criticism over a compensation arrangement with hedge funds that are

backing him related to his possible service on GM’s board. He could receive anywhere from 2% to 4%

of the upside of their GM shares over three years. Mr. Wilson owns about 30,000 GM shares, while the

funds backing him collectively own more than 30 million, or about 2% of the shares outstanding.

Mr. Wilson, among the architects of GM’s 2009 government bailout and bankruptcy restructuring, last

week was criticized by Warren Buffett , who suggested the pay arrangement created a short-term

incentive. “It’s just not the way to run a business,” said Mr. Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is a

GM shareholder, on CNBC. Mr. Wilson responded that he has held GM stock since 2011 and expects to

for many years, and is willing to lock up any payouts in GM stock “for an extended period of time.”

Such compensation deals have sparked controversy at other companies including Dow Chemical Co.

Many company executives and advisers deride the practice as a “golden leash” that compromises

independence and a director’s duty to serve all shareholders and weigh the long-term.

Activist investors contend such payouts motivate their director selections to shake up boardrooms and

increase value for all shareholders.

34

Mr. Wilson ended up on the board of Sotheby’s last year as part of activist investor Daniel Loeb ’s

settlement with the auction house for three board seats. Domenico De Sole, lead independent director at

Sotheby’s, bemoaned the proxy fight. “I thought it was an unfortunate expenditure of money for

someone who turned out to be an exemplary board member,” said Mr. De Sole, a former Gucci chief

executive. He said Mr. Wilson “really knows how to draw the line between governing and managing”

and can work with executives without overstepping boundaries.

Steve Wolosky, a partner at law firm Olshan Frome Wolosky LLP who represents activist investors,

says Mr. Wilson’s compensation is justified and his offer to lock up any payments “clearly evidences his

long-term commitment to improving value at GM.” Mr. Buffett later during the CNBC interview said:

“If Harry has a ton of stock himself that he’s going to put away for a long period of time, that’s one

thing.”

Still, some management lawyers find Mr. Wilson’s deal problematic.

“I don’t care how long he locks up the payouts,” said Avrohom J. Kess, a partner at Simpson Thacher

Bartlett LLP. He said Mr. Wilson instead should defer any payments unless GM’s stock is up a decade

from now. “That’s putting your money where your mouth is.”

The pay agreements are sometimes fraught but have improved over the years, said Robert Jackson, a

Columbia University Law School professor. The debate over Mr. Wilson’s arrangement “is a bit of a red

herring,” he said, adding that three-year compensation horizons for directors are “absolutely standard.”

http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-regulators-revive-work-onincentive-pay-rules-1424132619?KEYWORDS=mcgrane

U.S. Regulators Revive Work on

Incentive-Pay Rules

Compensation That Rewards Excessive Risk Taking Is a Concern

By

35

VICTORIA MCGRANE And

ANDREW ACKERMAN

Feb. 16, 2015 7:23 p.m. ET

26 COMMENTS

WASHINGTON—U.S. financial regulators are focusing renewed attention on Wall Street pay and are

designing rules to curb compensation packages that could encourage excessive risk taking.

Regulators are considering requiring certain employees within Wall Street firms hand back bonuses for

egregious blunders or fraud as part of incentive compensation rules the 2010 Dodd-Frank law mandated

be written, according to people familiar with the negotiations. Including such a “clawback” provision in

the rules would go beyond what regulators first proposed in 2011 but never finalized.

The clawback requirement, which is being hashed out among six regulatory agencies, would be part of a

broader compensation program in which firms are required to hang onto a significant portion, perhaps as

much as 50%, of an executive’s bonus for a certain length of time. The Dodd-Frank law included

provisions for an incentive-compensation rule to help ensure Wall Street incentive packages are aligned

with a company’s long-term health rather than short-term profits.

Exactly which firms will be covered is still a matter of debate among the agencies involved in the

discussions, but the 2010 law requires regulators to impose incentive-compensation rules on banks,

broker dealers, investment advisers, mortgage giantsFannie Mae and Freddie Mac and “any other

financial institution” deemed necessary. It also remains to be seen what type of behavior—besides

fraud—would trigger a clawback and whether conduct identified by the firm or regulators would

necessitate reclaiming compensation.

Some banks are already voluntarily recouping money from employees who engage in misconduct or

excessive risk. J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. clawed back about two years’ worth of total compensation

from three traders involved in the 2012 “London whale” trading debacle, which cost the firm $6 billion.

Many banks have implemented stricter bonus practices since the 2008 financial crisis, including

deferring more pay and linking more compensation to longer-term performance.

Advertisement

Shareholder activists say the existing clawbacks some firms have are too weak and that it remains

unclear how often those policies are invoked because banks don’t usually disclose when the tool is used.

The New York City comptroller has been successful in getting banks such as Citigroup Inc. and Wells

36

Fargo & Co. to expand their clawback policies in recent years. But many big banks have resisted the

office’s efforts to have them routinely disclose when and how much compensation they claw back,

according to the comptroller’s office.

“While many banks now have strong clawback policies on paper, absent disclosure, it’s impossible for

investors to know when and how they are being applied,” New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer

said in an email statement.

Related Video

U.S. financial regulators are focusing renewed attention on Wall Street pay and are designing rules to curb

compensation packages that could encourage excessive risk taking. Victoria McGrane joins MoneyBeat. Photo:

Getty

American Bankers Association CEO Frank Keating discusses proposals to reign in Wall Street risk and bonus

pay, as well as the debate over additional funding to enforce Dodd-Frank regulations. Photo: AP.

Work on the incentive-compensation proposal has renewed after more than three years of dormancy, but

the details are far from settled. At the end of last year, informal discussions among staff from the various

agencies prompted the three major bank regulators—the Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of

the Currency and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.—to send a conceptual proposal to the Securities and

Exchange Commission, according to people familiar with the discussions. The document sparked

several areas of debate, including how long the deferral period should be and how to treat asset

managers under the rule.

Fed governor Jerome Powell in a Jan. 20 speech said regulators plan to reissue a revised draft proposal

for public comment, though he didn’t give a specific timeline.

He hinted at the contours of banking regulators’ proposal, saying regulators are aiming at “deferral of

larger amounts of compensation over a longer period for people who are senior in these companies or

important risk takers” and for that compensation to come “in particular form…with particular triggers

for forfeiture and clawback.”

He said forfeiture should happen when “there appears to have been risk-management errors

or…malfeasance.”

37

As for clawbacks—or plans that require employees return compensation already paid if losses occur

later—Mr. Powell said “that’s fairly extreme, but there should be the possibility for that.”

Big Wall Street banks have instituted their own changes to their bonus pay practices since the financial

crisis, with the encouragement of regulators and shareholders. Many banks moved to defer more of

employees’ bonus payments over several years and give more of those bonuses in stock as opposed to

cash compared with the years preceding the 2008 crisis, consultants say. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in

January disclosed it would subject part of top executives’ bonuses paid in restricted shares “to

performance conditions” going forward.

The banks “went way further than anybody else in financial services and that became a competitive

disadvantage to get people [and] keep people,” said Alan Johnson, managing director of Johnson

Associates.

Yet some banks have already begun reversing some of those moves in the face of rising competition for

talent from hedge funds and asset-management firms, paying more cash and delaying a smaller portion

of bonus payments, consultants say. Late last year,Morgan Stanley announced it would defer for several

years about half of employee bonuses, down from an average of about 80% at its peak a few years ago.

A 2014 analysis by Johnson Associates estimated about 36% of a $1 million bonus on Wall Street is

deferred, compared with 45% in 2010.

In October, President Barack Obama gathered the heads of the top U.S. financial regulators for a White

House meeting and urged them to finish the outstanding compensation rules required by the 2010 DoddFrank law, a White House spokesman said at the time. Top Fed officials including New York Fed

President William Dudley have stressed that changing compensation practices can help address ethical

lapses on Wall Street.

Work on the rule had stalled after an initial proposal in March 2011 sought to have the largest financial

firms—those with $50 billion or more in assets—hang on to at least half of the bonuses paid to top

executives for at least three years. Smaller firms with at least $1 billion in assets would be subject to less

prescriptive rules but would have to get the signoff from regulators.

The Fed, OCC and FDIC circulated their draft proposal at the end of last year in a bid to move

negotiations forward with the SEC by securing their agreement on the concepts or soliciting changes,

38

one person close to the discussion said. It follows a pattern that regulators followed to restart work on

the high-profile Volcker rule in 2012. It is unclear if the document was shared with the other two

agencies tasked with writing the rule, the National Credit Union Administration and the Federal Housing

Finance Agency.

One flash point in the current talks is how long firms should defer compensation for executives,

according to people familiar with the discussions. It is still early and officials haven’t landed on a

specific period yet, a person familiar with the matter said. The debate over the rule is said to at least

partly mirror the 2011 proposal, when Republican members of the SEC objected to any mandatorydeferral requirement, saying the agency was poorly equipped to dictate the specifics of how individuals

must be paid at companies.

Another wrinkle, according to a person familiar with the discussions, is how to apply the rule to

financial institutions that have different methods for compensating executives than a traditional bank.

For instance, regulators are still debating how to defer the compensation—and potentially claw some of

it back—from an asset manager, who is primarily compensated with “carried interest” as opposed to a

salary and year-end bonus, the person said. Carried interest is a share of a partnership’s profits. Still, the

rule has the potential of capturing hedge funds, private-equity firms and investment advisers that haven't

been covered by prior efforts to regulate executive compensation.

Also up in the air is whether the rule would apply to fraud or excessive risk taking that occurred before

the regulation was in place.

The ECONOMIST

Activist funds

An investor calls

Sometimes ill mannered, speculative and wrong, activists are rampant. They will change American capitalism

for the better

39

Feb 7th 2015 | From the print edition

IMAGINE that you are an American CEO. You have just spent your week dealing with the damned

regulators, the latest BS on social media, the lawyers and their ever more brain-aching rules about what you

can say and to whom, a president in Washington who urges you take a patriotic rather than merely lawabiding stance to paying taxes and campaigners who think it is your corporation’s obligation to reduce social

inequality. You finally get a moment to do the job you are remarkably well paid for—running a global firm in

the pursuit of long-term profit—when the phone rings. It’s a banker on the line.

“Hello? We’re hearing rumours that an activist hedge fund has bought 4.9% of your shares.” Activists are

not, in this instance, tree-huggers who dislike what your company is doing to the atmosphere. They are

hedge funds that seek to shake up your company’s management. It is like a ruler hearing rumours of a coup.

It is the call that every CEO in America dreads getting—or has already received.

In the 1980s activists were called corporate raiders and were the jackals of capitalism, outcasts that

attacked and dismembered weak companies to widespread opprobrium but consoling profit. They were

immortalised in the film Wall Street, whose charismatic criminal, Gordon Gekko, showed his mettle by

treating greed as good and lunch as for wimps. They faded from prominence after a series of scandals and

the collapse of the junk-bond market in the late 1980s.

40

Today activism is mainstream and arguably the biggest preoccupation of America’s boardrooms. The

current activist crop are not the red-in-tooth-and-braces raiders of the 1980s; but they are determined to

shake up the companies in which they invest, shaking that very often leads to change in the corner office.

Since 2011 activists have helped depose the CEOs of Procter & Gamble and Microsoft, and fought for the

break up of Motorola, eBay and Yahoo—which on January 27th said it would spin off its stake in Alibaba, a

Chinese internet firm, after pressure from Starboard Value, an activist. They have won board seats at

PepsiCo, orchestrated a huge round of consolidation across the pharmaceutical industry, and taken on Dow

Chemicals and DuPont.

Neither age, status nor systemic importance offers any protection. Activists have removed the management

of the oldest firm on the New York Stock Exchange, Sotheby’s. They have won a board seat on Bank of

New York Mellon, a too-big-to-fail bank at the heart of the global financial system. And they have attacked

the world’s most valuable company, Apple. The chairman of one of Silicon Valley’s biggest firms admits,

“We think about an attack all the time.” A CEO with a superb record of running a giant industrial firm says

that a slip up would make him vulnerable. Inside activists’ offices you can have breezy chats about

dismantling pillars of the establishment like Ford and Citigroup.

Since the end of 2009, 15% of the members of the S&P 500 index of America’s biggest firms have faced an

activist campaign, according to FactSet, a research firm, and estimates by The Economist—a “campaign”,

here, being an effort to change a firm’s strategy, acquire board seats or remove managers. As activists often

buy stakes in firms without going on to launch such campaigns that underestimates the number of scary

phone calls the CEOs must take. The Economist estimates that about 50% of S&P 500 firms have had an

activist on their share register over the same period. The only proven defence that a firm can offer is to not

be American in the first place; 80% of activist interventions are in America, where the culture and legal

system are better suited to shareholder revolts than those in Europe or Asia.

For some all this is the doctrine of shareholder value taken to an absurd extreme—“they are having a

serious impact on the economy and are an aggressive deterrent to investment, research and development

and employee training,” says Martin Lipton, a lawyer who advises many firms that come under attack. For

others activism is a breath of fresh air in the stuffy, complacent world of the big American corporation.

Money never sleeps

Back in the office of the CEO under attack a well oiled defence machine is slipping into action. Many big

firms practise “emergency drills” for this moment. The CEO will summon a war cabinet and the room will fill

with lawyers, bankers, experts in investor relations and spin-doctors to deal with the media. The first

casualty of an activist conflict is the CEO who underestimates his opponents.

41

Activists are a small sliver of the hedge-fund world. Hedge Fund Research (HFR), a research firm, says that

of about 8,000 hedge funds activists number just 71—less than 1%. But they are larger than most; at $120

billion under management the activists account for about 4% of the hedge-fund total (see chart 1). Their

clients now include many of the world’s big endowments, family offices and sovereign-wealth funds. And

their assets have risen by a factor of five over the past decade. In 2014 they raised $14 billion of new

money, a fifth of all flows into hedge funds.

42

A dossier prepared by an investment bank will help the CEO and his consiglieri understand who they are

dealing with. The big funds (see table) are differentiated by their vintage, staying power and propensity to

campaign, and by their belligerence once the game is afoot.

43

44

The old guard includes Carl Icahn, an outrageous and outrageously successful septuagenarian, who has

been on the warpath since the 1980s. Nelson Peltz has similarly deep roots, but rather more gravitas. Over

the years he has attacked Cadbury, Pepsi and Kraft.

The new establishment includes ValueAct, Third Point and Elliott Advisors, all of which earned their spurs in

the 2000s. Its most prominent figure is William Ackman of Pershing Square, who says Warren Buffett is his

inspiration. Mr Ackman has had some disasters, including J.C. Penny, a department store he tried to

resuscitate, but also some triumphs, including Allergan, a pharmaceutical firm that was taken over last year.

The industry’s young guns include Sachem Head and Corvex, set up by protégés of the old guard.

The established funds lock in their clients’ money for one to two years, more than the typical hedge-fund

lock-in of a few months. Last year Mr Ackman launched a $3 billion vehicle listed in Amsterdam with an

indefinite life.

In theory this allows activists to take a medium-term view. In practice most trade in and out of firms often—