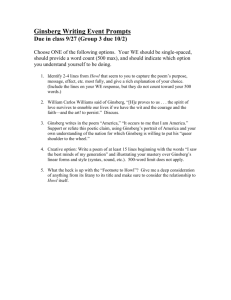

MacKenzie Bernard Mr. Jennings 6th Hour AP Lit (Warning: This

advertisement

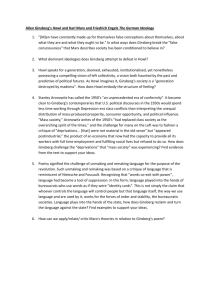

MacKenzie Bernard Mr. Jennings 6th Hour AP Lit (Warning: This essay will completely spoil a really great play.) I suppose I could write this essay about the literary merit of poems that have never been deemed worthy of an obscenity trial or a play that doesn’t revolve around a guy that f--ks a goat, but that doesn’t sound like as much fun. I didn’t read anywhere near the amount of books I’d planned on reading this summer (and believe me, I’m pissed at myself for that), but of what I did get around to, – which didn’t include a single piece of literature that I didn’t like or that I don’t think I could probably argue literary merit for – the two shortest works I read, Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems and Edward Albee’s The Goat, or Who is Sylvia?, stand out in my mind. Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems are the kind of Beat Generation-defining works that “discard the idea that life makes sense or that events add up to one coherent narrative or meaning” (Mr. Jennings, I hope you don’t mind if I borrow that quote from you). For Ginsberg, poetry, like life, wasn’t something that was supposed to make total sense. This basically translates to the fact that sometimes, Ginsberg’s poems are straight-up confusing. For example, his poem, “America,” has a sort of stream of consciousness, conversational style. The speaker (whose references to his own homosexuality, drug use, and friendship with William S. Burroughs (for example, lines 20, 54, and 93) pretty well indicate that the speaker is either Ginsberg or someone with a ton in common with Ginsberg) talks to America as if it was a person, which leads the speaker to spontaneously switching between topics every few lines. For example, lines 4-8 are “America when will we end the human war?/Go f--k yourself with your atom bomb/I don't feel good don't bother me./I won't write my poem till I'm in my right mind. /America when will you be angelic (4-8)?.” It can be hard to keep up with the free verse of Ginsberg’s speaker. The speaker also takes a different approach to America in almost every stanza. In the early stanzas, the speaker talks to America with a sardonic, confronting attitude. This quickly switches to a mocking realization that parts of himself are representative of exactly what he dislikes about America and eventually, to an understanding that America’s issues are actually preposterously serious. Multiple readings of “America” are likely to help a reader better understand Ginsberg’s spontaneous diction and various approaches towards America. It can also be helpful to reread Ginsberg poems such as “Howl,” which opens with the lines “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, Angel-headed hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night (1-7).” For me, the first time I read those lines my mind sort of overdosed on imagery. “Howl” goes on to create fixed bases through different repeated words which give the poem more rhythm than “America,” but like “America,” “Howl” has a stream of consciousness style, lacks a traditional meter, and spontaneously switches between subject after subject after subject. Like “America,” rereading “Howl” might help a reader clear any confusion prompted by Ginsberg’s unconventional writing and the same goes for the other eight poems in the book. If you took Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, condensed it into a play, and turned the protagonist into someone that’s into a goat instead of a little girl, you’d have Edward Albee’s The Goat, or Who is Sylvia?. Of “The Goat,” Albee claimed, “Every civilization sets quite arbitrary limits to its tolerances. […] It is my hope that people will think afresh about whether or not all the values they hold are valid.” Albee’s intention is to force his audience into questioning their “civilized” beliefs. To best do this, it is beneficial to reread “The Goat.” When the main character, Martin, admits to having a relationship with a goat named Sylvia, nobody (meaning his best friend, son, or wife) thinks twice about it. They automatically turn on Martin, label him as “goat f—ker,” and refuse any attempt he makes to help them understand. Albee wants his audience to do the exact opposite. Unlike the people closest to Martin, Albee doesn’t want his audience to make up their minds about bestiality (as well as infidelity, incest, and pedophilia, which are all seen in various parts of the play) in a second; he wants his audience to thoroughly think through these issues before they make up their mind about them. Reading “The Goat” multiple times can, at the very least, help a reader make a conscientious decision about these subjects. Rereading “The Goat” can also help a reader pick up on instances of foreshadowing. For example, in the second scene, Martin, describing his love at first sight for Sylvia, says: “I’d never seen such an expression. It was pure … and trusting and … and innocent; so guileless (80).” Martin’s wife, Stevie, responds, referencing their son: “(sardonic echo) Guileless; innocent; pure. You’ve never seen children, or anything? You never saw Billy when he was a kid (80)?”. In Scene Three, it’s revealed that Martin had an accidental sexual experience with Billy when Billy was a baby. That foreshadowing was something I didn’t catch until I read “The Goat” a second time. The same thing happened to me at the end of Scene Two when Stevie, fed up with Martin’s bestiality, storms out of the house, promising: “You have brought me down, and, Christ!, I’ll bring you down with me (89)!”. The first time I read that I just kind of thought “Oh, so, she’s gonna go sleep with his best friend. Cool.” Instead, at the very end of the play, Martin’s wife comes home dragging a dead Sylvia, which I wasn’t expecting at all. The second time I read it, I didn’t know how I didn’t see it coming. For me, at least, I caught a lot more of Albee’s foreshadowing the second time I read “The Goat” and it might be helpful for other readers to do the same. Howl and Other Poems as well as The Goat, or Who is Sylvia? are both worthy of rereading: Ginsberg’s poems mainly because he writes in a way that makes it really hard to fully grasp what he’s saying the first time through (at least if you’re sober); Albee’s play because the more you question the issues brought up in “The Goat,” the better reading you’ll have of it. Plus, you’ll catch all of his foreshadowing. I kind of want to throw in this Walter Van Tilburg Clark quote from the 1957 obscenity trial over “Howl:” The only final test, it seems to me, of literary merit, is the power to endure. Obviously such a test cannot be applied to a new or recent work, and one cannot, I think, offer soundly an opinion on the probability of endurance save on a much wider acquaintance with the work or works of a writer than I have of Mr. Ginsberg's or perhaps even with a greater mass of production than Mr. Ginsberg's. ... Aside from this test of durability, I think the test of literary merit must be, to my mind, first, the sincerity of the writer. I would be willing, I think, even to add the seriousness of purpose of the writer, if we do not by that leave out the fact that a writer can have a fundamental serious purpose and make a humorous approach to it (Morgan and Peters, 155-156). I think that’s a nice way to put literary merit and I think that’s something both Howl and Other Poems and The Goat, or Who is Sylvia? live up to. These are works that because they can be read, reread, and rereread (I’m borrowing that phrase from Mr. Esselman), live up to the AP definition of literary merit, but if it’s ok to throw in Clark’s definition too, it should also be noted that these are works written by incredibly sincere writers. Ginsberg was intent on defying any kind of traditional poetry or social convention; Albee was determined to force an audience to question societally accepted moral corruptions. In my mind, if rewarded rereading and/or sincerity are what determine literary merit, Ginsberg and Albee undoubtedly succeeded. Works Cited: Albee, Edward. The Goat, Or, Who Is Sylvia?: (notes toward a Definition of Tragedy). Woodstock: Overlook, 2003. Print. Ginsberg, Allen. Howl, and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket hop, 1956. Print. Morgan, Bill, and Nancy J. Peters. Howl on Trial: The Battle for Free Expression. San Francisco: City Lights, 2006. Print.