Ginsberg - University of Manitoba

advertisement

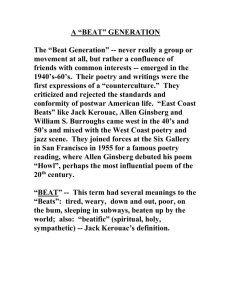

Allen Ginsberg Howl and other Poems Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Howl and Other Poems: The Scandal On 3 October 1955, at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, Allen Ginsberg began a legend with the first public reading of Howl. The Beat Generation had found its voice, and the museum has never been the same. Notoriety and litigation followed. Howl became a cause celebre in the fifties and its author a counter cultural institution and magnet for the media, ever thirsty for eye-catching exemplars of cultural change. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Despite the fact that it has been fashionable to say that Howl exploded on the American literary scene like a bombshell, that San Francisco finally “turned Ginsberg on”, and that this poem heralded in the Beat Generation, it is difficult to find in this admittedly extraordinary poem much that has not been anticipated in inchoate and sometimes even mature form in Empty Mirror. Howl is the crystallization of incipient attitudes and techniques of a new poetic direction or even a sudden eruption of outrage. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems It cannot even be said that Howl is unique in form or intention. It is the end of Modern Poetry. Most would agree that this type of poetry is one of the oldest traditions, that of the Minor poets in the Bible. Howl is not a genesis but an amplification of Modernity which brings to an end. Part of the reason for considering Howl an amplification has to do with the end of a poetic nihilism literature that began at the beginning of the XXth century. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The furor surrounding its initial publication was like a shot head round the world. The poem was enshrouded by such sensationalism during the months of litigation that immediately followed its release that there was little opportunity for sober, reflective digestion of it. Responsible commentary appeared mostly in Judge Horn’s court-room where the atmosphere was at least as much political as literary. A testimony made by a prosecution witness stated: “You feel like you are going through the gutter when you have to read that staff”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems However, Lawrence Ferlinghetti said: “If nothing else, the legal proceedings brought against Howl for obscenity served to make it easily one of the best selling volumes of poetry en the twentieth century. Ferlinghetti adds: It is not the poet but what he observes which is revealed as obscene. Society is obscene. The great obscene wastes of Howl are the sad wastes of a mechanized world, lost among atom bombs and insane nationalisms. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems For an unsuspecting popular audience, the poem recorded the despair and desolation of a strange and threatening population of “Angelheaded hipsters,” who were alienated, disaffiliated, and “destroy by madness, starving hysterical naked / dragging themselves through the Negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix”. Ginsberg and the Beat Attitude (Hipster: a young person, disillusion, extravagant) I feel as if I am at a dead End and so I am finished. All spiritual facts I realize Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Are true but I never escape The feeling of being closed in And the futility of all done and said. Maybe if I continued things Would please me more but now I have no hope and I a tired. The Empty Mirror begins with a poetic statement of the profoundest fatigue and hopelessness which will be carried out in Howl. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The poem expresses not exultation, not the certitude of a life that has found comfort in the evidence of things unseen, but the mood of a spirit that has long been besieged by doubts and has experienced a face-to-face encounter with the enervating spectre of despair. “I am tired,” the poet says, and in this weariness we hear the echo of the existentialist complains so familiar to us in the modern age. Kierkegaard might have diagnosed the malady as the “sickness unto death”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Like existentialism, the definitive boundaries of “beat” have been blurred both by the variety of attitudes that they enclose and by the notoriety that the popular press has brought to the term. The word is all to familiar with the “beatnik”, but it is less so with the philosophy behind the beard and sandals. The beat in the fifties was to feel the bored fatigue of the soldier required to perform endless, meaningless tasks that have no purpose, like Sisyphus. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Society imposed authority from without, but beatniks obeyed an authority from within. Viewed as a social phenomenon, they appeared “fed up” and recalcitrant –grumbling malcontents and irresponsible hedonists. Inwardly the case was quite different. The beatniks regarded themselves as pioneers, explorers of interior reality; in this respect, they resembled traditional religious mystics. Ginsberg’s visionary poetics is directed toward the poetry and the poetics and not toward an ultimate, divine saviour. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The beats’ much sensationalized use of drugs and hallucinogens only illustrates that their quest for inward reality had taken advantage of the resources of modern science. The incessant search for reality within was a quest for authenticity that reason, it was felt, indifferent to. It called for a exploration at the extremes of human experience, as far beyond the limits of reason as possible, thus placing uncommon stress upon subjective moods. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Unlike the rationalist they would not attempt to overcome their fears, guilt, dread, and cares; rather, they exploited these feelings in order to reach new levels of truth about themselves. Moods, they passionately believed, were indices of reality. Obviously, such a commitment to internal truth not only permits but demands the uninhibited confessions that tend to make conventional readers squirm. Most beat writers, especially Ginsberg, flaunt their most intimate acts and feelings –masturbation, sodomy, drug addiction, erotic dreams- in aggressively explicit street language. To the social conservative, it is shameless exhibitionism. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems To the beats, such expression is the denial of shame itself, a manifesto that nothing human or personal can be degrading. The beats assume the role of a nonbelligerent opposition, meeting the rigid rationalism of society with deliberate irrationality, in opposition to society’s (ir)rationality. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The beats were indifferent enemies of society but enemies nonetheless; because they were appalled by the ugliness of its materialism and goals and the emptiness of its values. They were indifferent because they have come to believe that they could not change society –change could only come from within. So beatniks chose not to fight. In the battle for social, spiritual, and aesthetic progress, they were conscientious objectors. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Disaffiliation and Death The words that were most often used to describe this posture were disaffiliation and disengagement. They felt that the only way one can call his soul his own is by becoming an outcast. They felt modern society had crashed the concepts of self and neighbour into a grotesque hypocrisies that reduced civilized living to an immense lie, the beats disaffiliated for the purpose of making interpersonal fidelity possible. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The truth about humanity –the truth that society obdurately censors – is shouted by Ginsberg in his “Footnote to Howl: Everything is holy! Everybody’s holy! Everywhere is holy! Everyday is in eternity! Everyman’s an angel. Religion Beats were prone to religious illumination, but the essential religious matrix of the beats, however, was in the Orient. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems This, because of its conception of the holiness of personal impulse. Zen Buddhism was particularly attractive. Every impulse of the soul, the psyche, and the heart was of holiness as shown in the Footnote to Howl. The Judeo-Christian dualism of good and evil is obliterated by the oriental relativism that neatly does away with the consequences of the spiritual pride that has bloodied the pages of Western ecclesiastical history. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems In the Hsin-hsin Ming or the Treatise of Faith in the Mind, a poem attributed to Seng-ts’an, a sixth century Zen master, can be found the following words: If you want to get the plain truth Be not concerned with the right or wrong The conflict between right and wrong Is the sickness of the mind The view represented by this fragment, that the conflict between right and wrong is an unnecessary and harmful concern, had enormous appeal for the beat writers. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The basic corruption of the “square world”, as they saw it, was its compulsion to be right. Because of this dualism, people suffered the burdens of shame and guilt, which seemed to them the most significant by-products of Western cultural psychology. And, shame and guilt were considered overwhelming obstacles to a view of life that celebrated the holy integrity of humanity and the world. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The Poem Howl For Ginsberg it is not a question of art imitating nature but art being nature. Ginsberg began experimenting with ways to restore speech to the language of poetry. Howl’s images obviously owe much to this counsel, but restoring speech to language entails more than just pronouncing a statement of intention. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems In the Indian Journal he declares that “the problem is to write poetry [...] which sounds natural, not self conscious”, defining literary self-consciousness. Not to be confused “simple sophomoric (self-assured, immature) recognizable egotistical self consciousness. Not natural to the man in the man – merely a stance. Self-consciousness, then, is an attitude, a stance, that is hostile to the spontaneity that quickens the ordinary mind, and here Ginsberg shows his allegiance to “open form”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Open form is the epistemological effort to postmodernist poetics to become equal rather than referential to reality. The writer follows no outside authority in creation but is wholly dominated during the creative act by the experience itself. This means, of course, that the pure reality of the experience cannot be adulterated by revision: […] whatever you said at that moment was whatever you said at that moment” Ginsberg points out. “So in a sense you couldn’t change, you could go on to another moment”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The poem is not about a subject; it is the subject itself. And there are several techniques in the writing of the poem. The first technique it is unselfconscious because it is not separate from the experience it enacts and therefore cannot reflect upon it. It is performance rather than artifact. By 1962 Ginsberg had moved in this subjective direction far enough to state: Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems […] how do you write poetry about poetry but making use of a radical method eliminating subject matter altogether…. I seem to be delaying a step forward in this field (elimination of the subject matter) and hanging on to habitual humanistic series of autobiographical photographs … although my own consciousness has gone beyond the conceptual to the non-conceptual episodes of experience, inexpressible by old means of humanistic storytelling. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The burden for readers of such open work is that they find themselves “naked” in the poem’s field. There is no conceptual apparatus, no formal tradition of “humanistic storytelling” to guide them. They are on their own. Thus images are for the body not the reason, and readers are expected to “avoid all irritable reaching after fact and reason” and to remain “in the absolute condition of present things”, that is, in the energy field of the poem itself. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems None of the classical critical approaches are relevant to Ginsberg’s open forms, for they are mesmerized by the metaphor of artist-as-maker and art as the object made. Talk, however, is an activity, a process, an event. True, it can be notated on then printed page, but its essential value is its movement. (Cage). We may only nod our head occasionally, widen our eyes in surprise, grimace in exasperation, or simply sigh, but in urgent conversation we are called upon to “do”, to react, to engage our energies with those of the poem. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The poetic quest for unadulterated reality involves, for poets like Ginsberg, breaking down “ the logical or necessary requirement of plot”. Since plot is a artifice, it cannot be life. A second technique is to make “the poem occasional in a new sense, a throw away rough jotting”. The roughness presumable equates with the real. Ginsberg comment that Howl was composed without thought to publication suggests his relation to this principle. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems A third technique, perhaps the most relevant to Ginsberg, is “luxuriating in the private and sensational at the expense of plot”. “The poem might be conceived as an orgasm, or a series of orgasms”, expressed in words like ‘Wow’, ‘Bomb’ and nonse-syllables, sputterings, pseudo-puns. The poet attempts to do away with the ‘one remove’, the imitation; the poem becomes, or is meant to become, the experience itself. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems On the positive side, one might see it as reflecting the emergence of apocalyptic poetry as an event in itself. It is not difficult to understand why the claim is so often made that Ginsberg’s poetry is unreadable. Ginsberg might be the first to agree; his poetry is not made to be read but to be lived through. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The theme of the poem is announced very clearly in the opening line. Then the following lines that make up the first part attempt to create the impression of a kind of nightmare world in which people representing “the best minds of my generation”, in the author’s view, are wandering like damned souls in hell. That is done through a kind of series of what one might call surrealistic images, a kind of state of hallucinations. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Then in the second section the mood of the poem changes and it becomes an indictment of those elements in modern society that, in the author’s view, are destructive of the best qualities in human nature and the best minds. Those elements are, I would say, predominantly materialism, conformity and mechanization leading toward war. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems And then the third part is a personal address to a friend of the poet or of the person who is speaking in the poet’s voice –those are not always the same thingwho is mad in the madhouse, and is the specific representative of what the author regards as a general condition. The Foot Note to Howl is the possibility of some hope. In Howl, Ginsberg explains, in 1969: You’re free to say any dam thing you want; but people are so scared of hearing you say what’s unconsciously universal that it’s comical. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems “So I wrote with an element of comedy – partly intended to soften the blow”. Howl was “typed out madly in one afternoon,” Ginsberg tells us, “a tragic custard-pie comedy of wile phrasing, meaningless images for the beauty of abstract poetry of mind running along making awkward combinations like Charley Chaplin’s walk…” Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems These comments speak to a sense of creative freedom, the aggressive irresponsibility of unrestrained whimsy and the deliberate indifference to personal and literary inhibitions of any sort. Ginsberg said: I Thought I wouldn’t write a poem but just write what I wanted to without fear, let my imagination go, open secrecy, and scribble magic lines from my real mind –sum up my life- something I wouldn’t be able to show anybody, write for my own soul’s ear and a few other golden ears. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems But Howl was also a declaration of metrical freedom. He explains the technique in a way that suggests the full extent of the sort of metrical freedom Howl demonstrates: I wasn’t really working with a classical unit, I was working with my own natural impulses and writing impulses. See, the difference is between someone sitting down to write a poem in a definite preconceived metrical pattern and filling in that pattern, and someone working with physiological movements and arriving at a pattern, and perhaps even arriving at a pattern which might even have a name, or might even have a classical usage, but arriving at it organically rather than synthetically. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Howl: Part I The first part of Howl is a list of the atrocities that have allegedly been endured by Ginsberg and his friends. More generally, these atrocities accumulate to form a desperate critique of a civilization that has set up a power structure that determines people’s “mode of consciousness…. Sexual enjoyment…. Different labours and loves”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The theme is clearly the same as Ginsberg’s essay: “Poetry, Violence, and the Trembling Lams” in which he pleads: When will we discover an America that will not deny its own God. Who takes up arms, money, police, and a million hands to murder the consciousness of God. Who spits in the beautiful face of Poetry which sings the Glory of God and weeps in the dust of the world. 55 This text is prose, but it could be easily inserted in the text of Howl without change. Even the structural device of the recurring word ‘Who’ is exploited, which demonstrates how blurred, even nonexistent, is the line between poetry and prose in Ginsberg’s work. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The word ‘Who’, Ginsberg has explained, was used in Howl “to keep the beat, a base to keep measure, return to and take off from again onto another streak (line) of invention.” One may even say that who was Ginsberg’s point of contact between vision and reality, an anchor that regularly brought his free flights back to earth and kept the poem from disappearing into the mists of a subjective wasteland. Howl is then rhizomatic writing. I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night, who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz, who bared their brains to Heaven under the El and saw Mohammedan angels staggering on tenement roofs illuminated, who passed through universities with radiant eyes hallucinating Arkansas and Blake-light tragedy among the scholars of war, who were expelled from the academies for crazy & publishing obscene odes on the windows of the skull, who cowered in unshaven rooms in underwear, burning their money in wastebaskets and listening to the Terror through the wall, who got busted in their pubic beards returning through Laredo with a belt of marijuana for New York […]. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems ‘Who’, it can be said, also served as an organizational strategy: by its sanction, otherwise unrelated chunks of inspiration could be thrown spontaneously into the poem. In other words, the device was a structural shield that kept “thinking” at bay, thereby allowing imaginative illumination and association unlimited freedom. Such technique is indicative of a poetic movement that is cumulative rather than logical or progressive, and it is uniquely suited to what Ginsberg calls an “expanding ego psychology”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Such a psychology, he states, “results in an enumerative style, the catalougin of a representative and symbolical succession of images, conveying the sensation of pantheistic unity” as it is shown particularly in the Footnote to Howl. The cumulative technique also goes back to the Hebraic roots that Ginsberg acknowledges as influences upon his work. *He notes that [...] the Hebraic poet developed a rhythm of thought, repeating and balancing ideas and sentences instead of syllables or accents. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems To read Howl properly, then, is to avoid the impulse to search for a logic or a traditional connection of ideas. Howl must be read with a new consciousness. The yardstick to measure the worth of the first part of Howl are basically two: the “tightness” of the ‘catalogue’ (images) and the maintenance of spontaneity. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The first measurement has to do with what Ginsberg calls “density” – the richness of imagery packed into a line. By and large, the poem does achieve density. Some might object that such richness is achieved at the cost of grammatical coherence. Ginsberg says that “Nature herself has no grammar” and so the classical grammarians definition of the sentence as “a complete thought” or as a construction “uniting subject and predicate” is simply at odds with reality. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems There is no completeness in nature and therefore there should be no completeness in the sentence. “The sentence … is not an attribute of Nature but an accident of man as a conversational animal”. It is no accident that the entire seventy-eight-line first section counts grammatically as a single sentence. The second measuring stick for evaluation Howl is its spontaneity. “But how sustain a long line in poetry”? Ginsberg asked himself. One perception must immediately and directly lead to a further perception, that is, in speed. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Spontaneity lives on speed, and the creating poet must avoid the lag. He does so, it seems, through association. There are many examples operative in the first part of Howl, but Ginsberg has specifically described the principle with reference to part two. He begins with a feeling, he says, that develops into something like a sigh. Then he looks around for the object that is making him sigh; the he ‘sighs in words”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems At best, he finds a word or several words that become key to the feeling, and he builds on them to complete the statement: Ginsberg explains that It is simply by a process of association that I find what the rest of the statement is, what can be collected around that word, what that word is concerned to. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Ginsberg says, “usually during the composition, step by step, word by word and adjective by adjective, if it’s at all spontaneous, I don’t know whether it even makes sense sometimes”. Spontaneity seems to require suspension of the rational faculties for the purpose of permitting the logic of the heart to operate freely. Testimony for this assertion is Ginsberg’s own: “Sometimes it does not make complete sense, and I start crying”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Clearly Howl, like most of Ginsberg’s work, follows a grammar of emotion. The “verification principle” is shifted from the logical positivists’ tests- Can I see it, smell it, taste it, hear it, o feel it? – to the simple test of the heart: “Does it make me cry”? Any analysis or explication of Howl would seem an affront to the poem’s very method, which is literally a violent howl of spontaneous, suprarational feeling. Ex post facto explanation appears an almost certain way of completely missing the point. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Christian parallels are unavoidable. The persecution of the early followers of Christ in Roman catacombs finds its counterpart in the despair of those “who lit cigarettes in boxcars boxcars boxcars racketing through snow toward lonesome farms in the grandfather night”, and those “who were burned alive in their innocent flannel suits in Madison Avenue taxicabs of Absolute Reality”. Finally, there is Carl Solomon, the supreme martyr – the archetype who is “really in the total animal soup of time”- to whom the poem is addressed. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Howl: Part II Part two of Howl, written under the influence of peyote, is an accusation: “what sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination”. (line 80) The protagonist “who” is now replaced, in an attempt to coordinate the structures of the two sections, by the antagonist “Moloch”. (Moloch, Molech or Molekh, representing Hebrew מלך mlk, (translated directly into king) is either the name of a god or the name of a particular kind of sacrifice associated historically with Phoenician and related cultures in north Africa and the Levante. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The unraveling of the j’acusse is painfully inevitable, and Ginsberg is thrown back upon the single resource of imagery. However, Ginsberg’s Hebraic lamentation on Moloch becomes increasingly powerful and leads to the conclusion where the “mad generation” is hurled “down on the rocks of Time” (line 95). Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The process of writing this second part is demonstrated by Ginsberg as follows: Partly by simple association, the first thing that come to your mind like “Moloch is” or “Moloch who”, and then whatever comes out. What sphinx of cement and aluminum bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination? Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing in armies! Old men weeping in the parks! Moloch! Moloch! Nightmare of Moloch! Moloch the loveless! Mental Moloch! Moloch the heavy judger of men! Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgement! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments! Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money! Moloch whose fingers are ten armies! Moloch whose breast is a cannibal dynamo! Moloch whose ear is a smoking tomb! Moloch whose eyes are a thousand blind windows! Moloch whose skyscrapers stand in the long streets like endless Jehovas! Moloch whose factories dream and choke in the fog! Moloch whose smokestacks and antennae crown the cities! Moloch whose love is endless oil and stone! Moloch whose soul is electricity and banks! Moloch whose poverty is the specter of genius! Moloch whose fate is a cloud of sexless hydrogen! Moloch whose name is the Mind! Moloch in whom I sit lonely! Moloch in whom I dream Angels! Crazy in Moloch! Cocksucker in Moloch! Lacklove and manless in Moloch! Moloch who entered my soul early! Moloch in whom I am a consciousness without a body! Moloch who frightened me out of my natural ecstasy! Moloch whom I abandon! Wake up in Moloch! Light streaming out of the sky! Moloch! Moloch! Robot apartments! invisible suburbs! Skeleton treasuries! blind capitals! demonic industries! spectral nations! invincible madhouses! granite cocks! monstrous bombs! They broke their backs lifting Moloch to Heaven! Pavements, trees, radios, tons! lifting the city to Heaven which exists and is everywhere about us! Visions! omens! hallucinations! miracles! ecstasies! gone down the I American river! Dreams! adorations! illuminations! religions! the whole boatload of sensitive bullshit! Breakthroughs! over the river! flips and crucifixions! gone down the flood! Highs! Epiphanies! Despairs! Ten years' animal screams and suicides! Minds! New loves! Mad generation! down on the rocks of Time! Real holy laughter in the river! They saw it all! the wild eyes! the holy yells! They bade farewell! They jumped off the roof! to solitude! waving! carrying flowers! Down to the river! into the street! Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems But that also goes along with a definite rhythmic impulse, like DA de de Da de de Da de de DA DA. “Moloch whose eyes are a thousand blind windows.” And before I wrote “Moloch whose eyes are a thousand blind windows”, I had the word, “Moloch, Moloch, Moloch, and I also had the feeling DA de de DA de de DA DA”. “So it was just a question of looking up and seeing a lot of windows, and saying, oh, windows, of course, but what kind of windows? But not even that ‘- “Moloch whose eyes.” “Moloch whose eyes”- which is beautiful in itself- but what about it, Moloch whose eyes are what?” Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems “Thousand blind windows”. And I had to finish it somehow. So I had said “windows”. It looked good afterward”. Ginsberg emphasizes the word afterward because the spontaneity of his poetry depends upon the existentialist formula: existence precedes essence. While he is writing, he is living (existing) through the experience. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems “The structure of Part II, pyramidal, with a graduated longer response to the fixed base (Ginsberg)”. “Moloch”, the symbol of social illness, was the metrical anchor in part two for a series of graphic but predictable images. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Howl: Part III Part three begins suspiciously like a “peptalk” or a get- well card: “Carl Solomon! I’m with you in Rockland where you’re madder than I am” . Whether this assertion is a diagnosis or flattery hinges on the connotation one chooses for madness. Solomon, however, has been raised, through the bulk of accumulation, to the status of a symbol. This section only underlines what was already said in the first part: a lost, mad generation without hopes, ends up in an madhouse. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Howl: Part III Carl Solomon represents an example of the whole generation, a manifestation of madness and death. Carl Solomon! I'm with you in Rockland where you're madder than I am I'm with you in Rockland where you must feel strange I'm with you in Rockland where you imitate the shade of my mother I'm with you in Rockland where you've murdered your twelve secretaries I'm with you in Rockland where you laugh at this invisible humor I'm with you in Rockland where we are great writers on the same dreadful typewriter I'm with you in Rockland where your condition has become serious and is reported on the radio I'm with you in Rockland Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Whether the following explanation Ginsberg gave for the total pattern of Howl was premeditated or afterthought, even he would probably decline to say; but it does supply a workable rationale for the project. “Part I, a lament for the Lamb in America with instance of remarkable lamblike youths’. “Part II names the monster of mental consciousness that preys on the Lamb”. “Part III a litany of affirmation of the Lamb in its glory: “O starry-spangled shock of Mercy!”. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Since the Footnote presumes to offer a cure for the social illness (Moloch), it is appropriate that the structure of both sections be roughly parallel and that the word Holy should operate in the same manner as it counterpart, Moloch. Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! Holy! The world is holy! The soul is holy! The skin is holy! The nose is holy! The tongue and cock and hand and asshole holy! Everything is holy! Everything is holy! Everywhere is holy! Everyday is in eternity! Everyman’s an angel! The bum’s as holy as the seraphim! The madman is holy as you my sour are holy! […] Holy forgiveness! mercy! charity! faith! Holy! Ours! bodies! suffering! magnanimity! Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Howl marks the end of poetry as we have known it. It brings to an end Modernity and at the same time opens a new beginning to future poetry. His poetry is also closely connected to the musical work of John Cage and the painting of Jackson Pollock, who also brought down Modernity in their respective arts. At the same time it presents an allegory of the world we live in, one without hope and corruption. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Ginsberg describes what he sees in a language that devours itself. The poem is an allegory of the destructive powers of society, power out of control. It is also nightmarish representation of a whole generation which refused to be part of a decadent society. Finally, is a cry, a howl with no hope in sight, except madness and-or death. End Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Other Poems Appearing with Howl in the 1956 volume, were other significant poems, such as America and A Supermarket in California. America America is whimsical, sad, comic, honest, bitter, impatient, and yet, somehow, incisive. The poem refuses to settle on a consistent structure. It is monologue and then drifts off into mutterings against a hypothetical national alert ego. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The poem is an attempt to catch the mood of a particular attitude toward the United States without the interference of logic. It is a drunken poet arguing after hours with a drunken nation; and yet, through all the turmoil, the gibberish, and the illogicality, a broad-based attack, which rational discourse can only hint at, is launched against American values. The seemingly hopeless illogicality of the poem itself becomes a mirror for the hopeless illogicality it reflects. ‘America I’ve given you all and now I’am nothing’ (l1) Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Interspersed throughout the poem are lines that suggest almost all the attitudes, postures, and convictions of Whitman’s exuberant optimism toward America are turned into a disillusionment that suggest the breaking of a covenant: “America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing”/ ‘Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb’ (Lines 1, 5) This admission is followed late in the poem by an appeal to America to shake off its hypocrisy and be equal to Whitman’s challenge: “America when will you be angelic? / When will you take off your clothes?” (Lines 9-10) Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The sense of devastation is expressed by the following lines: “When will you look at yourself through the grave?” (line 10), shortly followed by the here-and-now position: “America after all it is you and I who are perfect not the next world” (Line 16). It also underlines the injustice that exists in America, a country that should have no injustice at all: “I say nothing about my prisons nor the millions of underprivileged/ who live in my flowerpots under the light of five hundred suns’ (Lines 51-53). Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems “I am obsessed by Time Magazine …/Movie producers… serious but me…. (Lines 41-48) expresses his impotence facing the ideology provided by the media and his exclusion from society. The poem continues in a jerky dialogue full of shifting issues, which only at the conclusion justifies nonsensical logic and its logical nonsense: “America this is the impression I get from looking in the television set / America is this correct?” (Lines 69-70) It also reveals the obsession that America felt towards Communism, an obsession that led to countless injustices: Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems ‘America you don’t want to go to war [….] America is quite serious. (Lines 62-67) The poem reveals the disappointment Ginsberg feels toward America and the total impossibility to change: “America this is the impression I get from looking in the television set/America is correct?” However the poet who refuses war is willing to do its part to make change happen: “It’s true I don’t want to join the Army or turn lathes in precision parts factories, I’m nearsighted and psychopathic anyway/America I’m putting my queer shoulder to the wheel’. (Lines 72-74) Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The poem is an indictment of American values, belligerence, and a culture of consumerism which will also be expressed in A Supermarket in California. A Supermarket in California A Supermarket in California is a study of the contrast between Whitman’s America and Ginsberg’s. True to the American idiom, the poet is pictured as “shopping for images” in the “supermarket” of American life. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Here is the poet as consumer filling his shopping cart for the ingredients of his among “Aisles full of husbands!” (Line 3). Implicit in his meditation is the question: what would Whitman have thought of America now? A dramatic reconstruction takes place: “I saw you, Walt Whitman, childless, lonely old grubber,/ poking among the meats in the refrigerator and eyeing the grocery boys”. (Line 5) Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The poet follows Whitman “in and out of the brilliant stacks of cans” (Line 6) (follows him also, in poetic technique), imaginatively feeling the presence of the “store detective” (Line 8) behind them. Even here, Ginsberg cannot help underscoring the illicitness of the poet’s position in society – both his own and Whitman’s. No doubt Ginsberg’s many brushes with the authorities helped nourish his obsession that the way of the true poet inevitably arouses police suspicion. But the poet can always enjoy freedom of the mind, which is suggested in the following lines: Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems We strode… in our /Solitary… frozen /Delicacy…. Cashier (Line 7) Fortunately, images cost nothing; they have already been paid for by those who have put them up for display, and this fact leads to the final meditation of the last stanza. “Where are we going, Walt Whitman? The doors close in an hour. Which way does your beard point tonight? (Line 10) Ginsberg asks. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The urgency of the question adds pathos to the appeal. There is not much time. What are the options, old “gray beard”? (Line 8), and then, at the end there is only solitude “Will we walk all night through solitary streets?… we’ll both be lonely”. (Line 13) Or will the poet and Whitman give up on their country out of disappointment, and “stroll dreaming of the lost America of love past blue automobiles in driveways, home to our silent cottage”? (Line 14) Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Despair and nostalgia seem the two alternatives, and the disciple is bewildered. The poem ends, as inevitably must, with a question: Ah, dear father…. Teacher…when Charon… (Charon: Greek god of Hell). Boat…. Lethe? (Line 15) (Lethe: Oblivion and river of joyfulness flowing through the Hades). Whitman’s America was quite different from the one Ginsberg saw around him. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Conclusion In Ginsberg poetry, perhaps the greatest burden falls on the readers of open poetry, for they, even more than the poets (who at least have the guidance of their own experiences to assist them) are truly “naked” in the open field. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems We are advised that an open poem is a re-enactment rather than an artifact and that they should concern themselves with absorbing the energies (rather than substance) that are “held” in kind of dynamic tension within the field of the poem. The images of the poems, by virtue of the solidarity that breath gives them, are allowed the free play of their individual energies, they are advised, even while, through juxtaposition with other images, they create an energy field. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The character of the engagement that readers are expected to have is radically different from that with which they are accustomed. We are asked to “avoid awareness”, …in the absolute condition of present things, that is, in the poem itself. In Whitman’s writing, Ginsberg recognized an astute critic of American democracy, not the cherubic optimist so often portrayed by critics. Whitman’s fundamental belief that only through a society based on “intense and loving comradeship” of man, real, lasting intimacy, unabashed, could the nation survive. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Ginsberg recognized Whitman as a kindred spirit, a rebel against both the literary establishment of his time and the government. Whitman´s longing for a truly civic America devoid of class distinctions, probably melded well with Ginsberg´s own upbringing. After the II War World Ginsberg did not buy the package of goodies offered by the emerging consumerism of the country was experiencing, nor could post-war optimism over a healthy economy placate yearnings for a greater sense of freedom. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems NOTES FOR HOWL AND OTHER POEMS* By 1955 I wrote poetry adapted from prose seeds, journals, scratchings, arranged by phrasing or breath groups into little short-line patterns according to ideas of measure of American speech. I suddenly turned aside in San Francisco, unemployment compensation leisure, to follow my romantic inspiration—Hebraic-Melvillian bardic breath. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems I thought I wouldn't write a poem, but just write what I wanted to without fear, let my imagination go, open secrecy, and scribble magic lines from my real mind— sum up my life—something I wouldn't be able to show anybody, write for my own soul's ear and a few other golden ears. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems So the first line of `Howl', `I saw the best minds', etc. the whole first section typed out madly in one afternoon, a huge sad comedy of wild phrasing, meaningless images for the beauty of abstract poetry of mind running along making awkward combinations like Charlie Chaplin's walk, long saxophone-like chorus lines I knew Kerouac would hear sound of—taking off from his own inspired prose line really a new poetry. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems I depended on the word `who' to keep the beat, a base to keep measure, return to and take off from again onto another streak of invention: `who lit cigarettes in boxcars boxcars boxcars', continuing to prophesy what I really knew despite the drear consciousness of the world: `who were visionary indian angels'. Have I really been attacked for this sort of joy? So the poem got serious, I went on to what my imagination believed true to Eternity (for I'd had a beatific illumination years before during which I'd heard Blake's ancient voice & saw the universe unfold in my brain), & what my memory could reconstitute of the data of celestial experience. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems But how sustain a long line in poetry (lest it lapse into prosaic)? It's natural inspiration of the moment that keeps it moving, disparate thinks put down together, shorthand notations of visual imagery, juxtapositions of hydrogen juke-box—abstract haikus sustain the mystery & put iron poetry back into the line: the last line of `Sunflower Sutra' is the extreme, one stream of single word associations, summing up. Mind is shapely, Art is shapely. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Meaning Mind practised in spontaneity invents forms in its own image & gets to Last Thoughts. Loose ghosts wailing for body try to invade the bodies of living men. I hear ghostly Academics in Limbo screeching about form. So these poems are a series of experiments with the formal organization of the long line. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems I had an apt on Nob Hill, got high on Peyote, & saw an image of the robot skullface of Moloch in the upper stories of a big hotel glaring into my window; got high weeks later again, the Visage was still there in red smokey downtown Metropolis, I wandered down Powell Street muttering, `Moloch Moloch' all night & wrote `Howl' ii nearly intact in cafeteria at foot of Drake Hotel, deep in the hellish vale. Here the long line is used as a stanza focus broken within into exclamatory units punctuated by a base repetition, Moloch. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The rhythmic paradigm for Part iii was conceived & half-written same day as the beginning of `Howl', I went back later & filled it out. Part I, a lament for the Lamb in America with instances of remarkable lamblike youths; Part ii names the monster of mental consciousness that preys on the Lamb; Part iii a litany of affirmation of the Lamb in its glory: `O starry spangled shock of Mercy.' The structure of Part iii, pyramidal, with a graduated longer response to the fixed base.... Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems A lot of these forms developed out of an extreme rhapsodic wail I once heard in a madhouse. Later I wondered if short quiet lyrical poems could be written using the long line. `Cottage in Berkeley' & `Supermarket in California' (written same day) fell in place later that year. Not purposely, I simply followed my Angel in the course of compositions. What if I just simply wrote, in long units & broken short lines, spontaneously noting prosaic realities mixed with emotional upsurges, solitaries? Transcription of Organ Music (sensual data), strange writing which passes from prose to poetry & back, like the mind. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems What about poem with rhythmic buildup power equal to `Howl' without use of repeated base to sustain it? A word on Academies; poetry has been attacked by an ignorant & frightens bunch of bores who don't understand how it's made, & the trouble with these creeps is they wouldn't know Poetry if it came up and buggered them broad daylight. A word on the Politicians: my poetry is Angelical Ravings, & has nothing to do with dull materialistic vagaries about who should shoot who. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems The secrets of individual imagination—which are transconceptual & non-verbal—I mean unconditioned Spirit—are not for sale to this consciousness, of no use to this world, except perhaps to make it shut its trap & listen to ti music of the Spheres. Who denies the music of the spheres denies poet denies man, & spits on Blake, Shelley, Christ, & Buddha. Meanwhile have ball. The universe is a new flower. America will be discovered. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Who wants war against roses will have it. Fate tells big lies, & the gay Creator dances ,-r his own body in Eternity. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems 55Nevertheless, a few generalizations and observations may prove helpful guideposts through this “animal cry” of human anguish. First, the poet sets himself up as observer in the opening line. He is witness to the destruction of “the best minds of my generation” by madness. Madness presumably is the state of civilization that the poet understands as hostile to the sentient (conscious) martyrs whose collective experiences under its tyranny are catalogue in a cumulative, cresting wave of relative clauses. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Second, at the same time, madness occurs thematically in the first part of the poem in other forms. For example, it is suggested that these martyrs have been attracted to what is implied as a mad quest: they are “burning for the ancient heavenly connection of the starry dynamo in the machinery of the night”, and they have “bared their brains to Heaven”. Further along in the poem it is mentioned that they “thought they were only mad when Baltimore gleamed (shined) in supernatural ecstasy”, which is later followed by a reference to Ginsberg’s own commitment to an asylum, and finally (line 70), Carl Solomon, who is undergoing treatment at Rockland State Hospital. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems There is a degree of ambivalence in the use of this crucial term madness in the first line. Does it reflect merely the “madness: as an officially acceptable level of reality that is uncongenial to the suffering heroes of the poem, or is it not possible that this destructive “madness” also describes the predicament of nonconformism? In other words, are not these martyrs self-destroyed because they refuse to live on the acceptable plane of official reality? In these terms, the “angelheaded hipsters” (beatniks) are embracing “madness” as an alternative to an unbearable sanity. Allen Ginsberg: Howl and Other Poems Their madness consists in their “burning for the ancient nonspiritual view of the world, in their “burning for the ancient heavenly connection” in a civilization that has proclaimed that God is dead. For this reason Ginsberg emphasizes their thinking: “they were only mad when Baltimore gleamed in supranatural ecstasy”.