syllabus- policies

advertisement

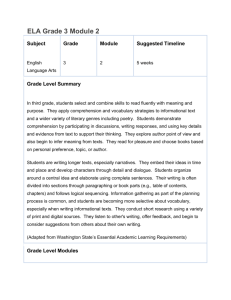

English 630-01: Early American Literature, the Electronic Archive, and the History of the Book Fall 2012 ● Tuesdays 3:30 – 6:20 ● MHRA 1213 Professor Karen Weyler Office: MHRA 3121 ● Telephone: 334-4689 ● Email: KAWeyler@uncg.edu Office hours: TR 12:30 – 2:00 p.m.; additional hours by appt. Required Texts Foster, Hannah. The Coquette and The Boarding School. Ed. Jennifer Desiderio and Angela Vietto. Peterborough: Broadview, 2011. ISBN 9781551119984. Mulford, Carla. Early American Writings. New York: Oxford UP, 2002. ISBN 9780195118414. Course Description The long eighteenth century was the age of revolution, witness not only to the American Revolution, but also to the so-called “reading revolution,” as more people than ever before achieved literacy and sought out books; at the same time, newspapers and periodicals began gaining traction in American political and cultural life. This course will explore the intersections among early American literature, history of the book, and genre studies. We will investigate how genre and the material form of texts shaped reading and writing practices and vice versa. Genres that we will consider include poetry and the commonplace book, personal narratives, captivity narratives, sermons, and novels, as they intersect with such printed media as the broadside, pamphlets, literary periodicals, and newspapers. Although we will read widely in early American writings, with a roughly chronological orientation, this course is not intended to be a survey. Course requirements include a major research paper as well as several shorter writing assignments involving exploration of electronic archives. These assignments will necessitate particular attention to the modes and conventions of academic writing. Student Learning Outcomes By the end of the semester, students will be able to: identify and use major scholarly resources for the study of eighteenth-century British America; describe how individual texts participated in broader religious, political, cultural, and literary movements; assess the changing valence of books and other printed media over the course of the eighteenth century; evaluate the contributions of major critical works to the study of the eighteenth century; identify the stylistic and contextual differences between a seminar paper and a journal article; write concisely and effectively in a variety of scholarly modes, including seminar papers, abstracts, and book reviews. Course Requirements and Evaluation Seminar Paper (15-18 pages) Class Participation Critical Book Review Database Investigations (total of 4) Abstract Assignment 50% 15% 10% 20% 5% Office Hours and Conferences You are welcome to visit my office at any point during the semester or to schedule an appointment outside of my usual office hours in order to discuss reading assignments, papers, etc. Classroom Courtesy All of us are responsible for creating a productive, civil learning environment, where we are focused on our conversations with one another. Please turn off and put away all electronic devices. I would prefer that you abstain from using laptops in the classroom, unless they are integral to the day’s work. I anticipate that our discussions will be lively, but we will always conduct ourselves with courtesy toward one another. Attendance Policy A successful seminar depends on a critical mass of participants who are on time, prepared, and eager to participate. Ideally, you won't miss any classes, but sometimes illness may prevent you from attending. Please be aware, however, that absences may negatively affect your grade. Three or more absences, regardless of excuse, will result in the student being dropped from the class if the absences occur before the drop date; after that time, they will result in failure. Policy on Incompletes I expect students to finish a course in the semester in which they are enrolled in it. Incompletes are an inefficient use of everyone’s time, and I grant them only under extraordinary circumstances. Academic Integrity Policy I expect every student to abide by the principles of the Academic Integrity Policy, which is available at http://academicintegrity.uncg.edu/complete/. You must properly document, using MLA style, any use of another's words, ideas, or research; unacknowledged use of someone else's thoughts is plagiarism. Work that is not properly documented will receive a zero; further penalties may be assessed according to the criteria established under the Academic Integrity Policy. If you have questions concerning documentation, please consult me. What Can You Expect from Your Professor? You can expect that I will treat you as an adult, encourage your participation in this class, listen carefully to what you have to say, and challenge your thinking. You can also expect me to evaluate your work fairly, offer constructive criticism and praise of your oral and written work, and evaluate your work in a timely fashion. Except under usual circumstances, I return all graded work within two weeks. 2 Course Calendar Please complete each day's readings before coming to class, with the exception of the readings marked review texts; those will be assigned individually. You should also read the author introductions and other introductory material. In case of inclement weather, you should be guided by the UNCG adverse weather policy. In case of class cancellation for any reason, please continue with your reading. This course calendar is subject to adjustment as needed. Tuesday Topic and Readings NB: If you feel you need additional background information on any of these topics or authors in order to prepare for class, take action: look in the MLA database to see what other scholars have written about these authors. You will get out of this and any other graduate course what you put into it. Part of becoming a professional is assessing your strengths and addressing your weaknesses. Aug. 21 Course Introduction Adams and Barker, “A New Model for the Study of the Book” (BB) Personal Narratives: Journals, Diaries, Conversion Narratives, and Letters Knight, The Journal 655-667 Ashbridge, Some Account 603-15 Adams, letters 1034-36; Travel Diaries 1029-34 Monaghan, “Literacy Instruction and Gender in Colonial New England” (pdf) Aug. 28 Questions to consider: Who comprised the intended audience for each of these texts? How do you know? What expectations of privacy, if any, did these writers have for their works? How were they shared or disseminated? Review text: Susan Clair Imbarrato, Traveling Women: Narrative Visions of Early America Database Investigation: North American Women’s Letters and Diaries. Be sure to look at the “Browse” button as you begin your explorations. Locate one series of correspondence or diary of interest to you from the pre-1800 era. Write a short summary of the document and explain what you find interesting about this document. How does your selected text illuminate our collective readings? How might you use such a text in your research or teaching? Sept. 4 Personal Narratives continued Edwards, Personal Narrative 669-76 Woolman, excerpts from Some Considerations on the Keeping of Negroes 616-20 and The Journal 620-28 Occom, A Short Narrative 868-72 Questions to consider: All three narratives relate conversion experiences. What evidence do they offer of their conversions? How might their texts be “useful” to readers? Unlike his sermon and hymns, Occom’s narrative was not published in his lifetime, nor does it seem to have been intended for publication. How should that fact affect our teaching of this narrative? 3 Sept. 11 Captivity Narratives Rowlandson, Narrative of the Captivity and Restauration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson 307-28 Radisson, The Relation of My Voyage, Being in Bondage in the Lands of the Irokoits 124-39 Review texts: Daniel Richter, Facing East from Indian Country: A Native History of Early America; Kathryn Zabelle Derounian-Stodola and James Levernier, The Indian Captivity Narrative 1550-1900 Sept. 18 Questions to consider: How do the captive subject’s religion, gender, and age shape his or her experiences? Is it possible to read across the grain in these narratives? What do we gain from doing so? Captivity Narratives continued Marrant, A Narrative of the Lord’s Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant 929-41 Kinnan, A True Narrative of the Sufferings of Mary Kinnan (EAL, First Series, 15 pp.) Review texts: Joanna Brooks, American Lazarus; Eileen Razzari Elrod, Piety and Dissent: Race, Gender, and Biblical Rhetoric in Early American Autobiography Questions to consider: Marrant’s and Kinnan’s narratives were written 100 years after Rowland’s narrative became the ur-text for the captivity genre. How has the genre evolved? What thematic issues endure? Which ones have disappeared? Neither Marrant nor Kinnan produced their narratives independently. They were collaborative productions recorded by an editor. How does that collaboration affect our understanding of “authorship”? What are the limits of authorship? Sept. 25 Database Investigation: Early American Imprints, First Series. Everything printed in British America prior to 1800 is included in Early American Imprints, First Series (with a few exceptions). How does one navigate such a massive database? What can looking at electronic versions of imprints tell you that a modern anthology cannot tell you? What are the limitations of such a database? Look up “captivity narratives” under the genre tab. How many do you find? Locate one captivity narrative new to you and write up a brief summary. What were the circumstances of that narrative’s publication? How can we gauge its popularity and/or influence? How does this narrative reinforce or alter what you learned from the narratives we read as a class? Sermons Edwards, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God 676-84; The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit 684-87 Chauncy, Enthusiasm Described and Caution’d Against 688-94 Occom, A Sermon Preached by Samson Occom 872-82 Review texts: Lisa Smith, The First Great Awakening in Colonial American Newspapers; Patricia Bonomi, Under the Cope of Heaven; Daniel Cohen, Pillars of Salt, Monuments of Grace: New England Crime Literature and the Origins of American Popular Culture Questions to consider: Sermons were what David Hall has named “steady sellers.” What explains their appeal in the 18th century? Look up “Execution Sermons” in Early American Imprints. How many do you see? Why would this particular type of sermon appeal so strongly to readers? 4 Oct. 2 Poetry: Commonplace Books, Newspaper Poetry, Magazine Verse, and Broadsides Broadside Workshop Wheatley, “On the Death of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield” 891 (read version in text as well as online in Early American Imprints, First Series); “To the University of Cambridge” 890; “On Being Brought from Africa to America” 890-91; “To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth” 89394; Letter to Occom 897 Questions to consider: What modes of poetry were popular in the eighteenth century? How was each of these texts shared or not shared at the time of its composition? How do medium and mode of dissemination shape and affect the reading experience? Look up “broadsides” in Early American Imprints. What kinds of poems were published in broadside format? What other kinds of texts were published as broadsides? Print out one example to bring to class for sharing and discussion. Oct. 9 Review texts: Max Cavitch, American Elegy; Catherine La Courreye Blecki and Karin A. Wulf, eds., Milcah Martha Moore’s Book Poetry continued Turrell, [Lines on Childbirth] 816; [Lines on the Death of Mother] 815 Stockton, “Addressed to General Washington” 833-34; “By a Lady to Her Husband in England” 830; “A Poetic Epistle” 832-33; “To a Visitant” 830 Freneau, “The Island Field Negro” (aka “To Sir Toby”) 1081; “The Indian Burying Ground” (BB); “On Mr. Paine’s Rights of Man” (BB); “The Wild Honeysuckle” (BB) Review texts: Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities; Carla Mulford, ed., Only for the Eye of a Friend: The Poems of Annis Boudinot Stockton Database Investigation: The standard newspaper database is America’s Historical Newspapers. Colonial Williamsburg has also produced an exceptionally fine electronic archive of the newspapers titled the Virginia Gazette (actually four papers, published by different editors between 1730-1780). The search tools and indexing are easier to navigate than America’s Historical Newspapers, but you should look at both. Pick one newspaper and briefly describe its publication history. What was the standard format and organization of the paper? What kind of “news” predominated? You will find the VG here: http://research.history.org/DigitalLibrary/BrowseVG.cfm. Oct. 16 Questions to consider: Newspapers were major sources of poetry, both of general interest and what we call “local poetry”—that is, written about the concerns and issues relevant to a particular community. What types of poetry were popular in the newspaper you selected? Did the paper favor reprints or original contributions? Print out several samples of newspaper poems and bring to class to share. No Class Meeting: UNCG Fall Break Please submit your seminar paper proposals to my mailbox no later than Friday, Oct. 15, so that I may return them on Oct. 23rd. 5 Oct. 23 Literary Magazines and Pamphlets Murray, “On the Equality of the Sexes” 1040-44 and “Desultory Thoughts” 1045-46 Warren, “Letter to the Independent Chronicle” (on Chesterfield) 1010-11 Benjamin Rush, Thoughts Upon Female Education (EAI, First Series) NB: If you are not familiar with Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication, you should read at least an excerpt, but preferably the whole text. Database Investigation: American Periodicals. Locate a periodical that was published prior to 1820. Glance through one entire number. How is the content proportioned among fiction/poetry/biography/non-fiction, etc.? Does the periodical favor anonymous publication, or does it name authors? How many pieces appear to be reprints from other periodicals or books? Who is the intended audience? How do you know? If you are overwhelmed by choices, choose either The Gleaner, edited by Judith Sargent Murray, or one of the two periodicals edited by American novelist Charles Brockden Brown: The Monthly Magazine or The Literary Magazine Review texts: Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic; Susan Branson, These Fiery Frenchified Dames; Jared Gardner, The Rise and Fall of Early American Magazine Culture Oct. 30 Questions to consider: What were the standard expectations for female behavior? What rhetorical strategies does each author use to stake out new ground for women? What new roles for women does each author imagine? The Novel Foster, The Coquette Review texts: Cathy Davidson, Revolution and the Word; Julia Stern, The Plight of Feeling: Sympathy and Dissent in the Early American Novel Nov. 6 NB: The standard database for early American fiction is Early American Imprints, First Series (1639-1800) and Second Series (1800-1819). The standard database for American fiction through the early 20th century is Wright American Fiction, 1774-1905. Unfortunately, UNCG has access only to the later portion of this database. The Novel continued Amelia (BB) Foster, The Boarding School All contextual materials in the Desiderio and Vietto edition of The Coquette and The Boarding School Abstract Writing Workshop Nov. 20 Questions to consider: We are reading Amelia as part of the “Just Teach One” project, which I will explain in more detail in class. In brief, however, this collaborative scholarly project aims to expand and diversify the teaching of early American fiction, with results reported in Commonplace. What new or different ground does Amelia stake out for American women? How does reading Amelia shape your understanding of The Coquette, and vice versa? No Class Meeting: Use this time to work on your seminar paper. I will hold office hours for paper consultations during our regular meeting time. Seminar Paper Presentations Nov. 27 Seminar Paper Presentations Nov. 13 6 Karen Weyler English 630 Writing Assignments and Oral Presentations Please use a 12 point font and double space everything you submit in this class. 1) Critical Book Review This assignment will introduce you and your classmates to major works of literary criticism and historiography as well as to give you practice in writing a book review. You will be responsible for explaining to the class the central argument(s) of the book, along with the critic's general approach and supporting evidence. Explain the methodology, flaws or gaps in the argument, etc. How does the subject of your book converge with our class discussions? What new perspectives does it offer us? How might it be useful to your classmates? Your review should be no more than 3 pages in length. A good rule of thumb for reviews is to aim for about 2/3 summary and 1/3 analysis. For models, look at recent reviews in American Literature or Early American Literature. Prior to class, please upload a copy of your review to the Discussion folder on Blackboard. Bring to class two copies of your review—one to give to me at the beginning of class, and the other to use as you summarize your review for the class. You will have 5 minutes to discuss your book. Be prepared to answer questions about your topic and how it relates to or converges with our other reading assignments. Make sure you obtain a copy of your book as soon as it is assigned. Some titles may need to be ordered through Interlibrary Loan. 2) Database Investigations You will explore 4 major electronic archives and provide written reports of your findings. These archives are treasure troves. They will be rich sources of inspiration for your seminar papers, and you will be amply repaid for the time you spend exploring these databases. I have provided a few guiding questions for each database. Your report, however, will be shaped largely by what you find. Each database report should be approximately 2-3 pages in length. We will use these reports to generate class discussion. Always be prepared to discuss what you found, why it’s interesting, how it enriches our shared readings, and what we might do with it. 3) Seminar Paper Abstract Submissions to conferences and many journals require an abstract, as do dissertations. What should an abstract do? How long should it be? We'll conduct a workshop on abstract writing later in the semester. 4) Seminar Paper and Presentation Each student will develop an original 15-18 page research paper. Research paper presentations are scheduled for the last two weeks of the semester. You will deliver a short version of your essay to your classmates, with time allowed for discussion. Each student will also serve as a respondent to another student's paper. I’ll hand out the formal assignment for the seminar paper at the end of September (including the requirements for the prospectus, bibliography, and abstract), but you should begin thinking about possible topics. Your project may focus on any author or text that appears on our syllabus. If you wish to purse research on a different text relevant to our studies, please discuss it with me. All projects must fall within the pre-1800 era. 7