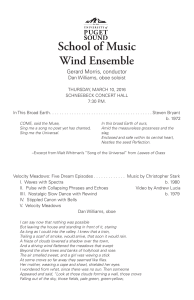

Modest MUSSORGSKY (1839 – 1881) Pictures at an Exhibition His

Modest MUSSORGSKY

(1839 – 1881)

Pictures at an Exhibition

His musical education was erratic, he toiled as a civil servant and wrote music only part-time, influenced few if any of his contemporaries, died early from alcoholism, and left a small body of work. Yet, Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (1839-1881) was a towering figure in nineteenth century Russian music. His works exhibit a daring, raw individuality and unique sound that wellmeaning associates tried to conventionalize and correct. He is best known for Night on Bald Mountain, Pictures at an Exhibition, and the opera Boris Godunov - each one full of arresting harmonies, disturbing colors, and grim celebrations of Russian nationalism. He had difficulty finishing works in larger formats, but his music circulated widely enough that, by the late 1860s, he was cast with Balakirev, Cui, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Borodin as part of Russia's "Mighty Handful." When he died in 1881, he left it to posterity to sort through and complete his unfinished works of unruly genius.

In 1870, Mussorgsky met artist and architect Viktor Hartmann. Both men were devoted to the cause of an intrinsically Russian art and quickly became friends. When Hartmann died at the age of thirty-nine, little did he know that the paintings that he left behind—the legacy of an undistinguished career as artist and architect—would live on in another artistic form. The idea for an exhibition of Hartmann’s work came from the influential critic Vladimir Stassov, who organized a show in Saint Petersburg in the spring of 1874. But it was Modest Mussorgsky, so shocked at the unexpected death of his dear friend, who set out to make something of this loss. “Why should a dog, a horse, a rat have life,” he is said to have asked, paraphrasing King Lear, “and creatures like Hartmann must die?” Stassov’s memorial show gave Mussorgsky the idea for a suite of piano pieces that depicted the composer “roving through the exhibition, now leisurely, now briskly, in order to come closer to a picture that had attracted his attention and, at times, sadly thinking of his departed friend.” Mussorgsky worked feverishly that spring and, by June 22,

1874, Pictures from an Exhibition was finished. There is no record of a public performance of the work during Mussorgsky’s lifetime, so it was left to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, the musical executor of Mussorgsky’s estate, to edit the manuscript and bring the work to the light of day nearly five years after the composer’s death. Unfortunately, the Rimsky-Korsakov edition contained a great deal of editing as well as some outright errors, so it wasn’t until 1931, more than half a century after the work's composition, that Pictures at an Exhibition was published in a scholarly edition in agreement with the composer's manuscript.

The Russian-Georgian opera conductor Mikhail Tushmalov (1861 - 1896) is mostly known today as the first person to have prepared an orchestral version of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition. Tushmalov's version sets an abridged version of the work (it omits Gnomus, Tuileries and Bydlo together with all of the Promenades except for the fifth) and may have been completed as early as 1886, when Tushmalov was a student of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, gaining him access to Mussorgsky’s manuscript through his teacher. The first performance of Tushmalov's orchestration was conducted by Rimsky-Korsakov in

Saint Petersburg on November 30, 1891. Tushmalov's score is often described as dark and restrained in color, and thus more authentically 'Russian' in its approach to the score than subsequent orchestrations. Tushmalov was but the first of many orchestrators, including Sir Henry Wood, Leo Funtek, Maurice Ravel, Leonidas Leonardi, Lucien Caillet, Leopold Stokowski,

Arturo Toscanini, Nikolai Golovanov, Walter Goehr, Vladimir Ashkenazy, and Lawrence Leonard to have taken on the task of orchestrating the work.

Promenade. According to Stassov, this section depicts Mussorgsky "roving through the exhibition, now leisurely, now briskly in order to come close to a picture that had attracted his attention, and, at times sadly, thinking of his friend."

The Old Castle. A troubadour sings a doleful lament before a foreboding, ruined ancient fortress.

Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks. Hartmann's costume design for the 1871 fantasy ballet Trilby shows dancers enclosed in enormous eggshells, with only their arms, legs and heads protruding.

Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle. Mussorgsky originally called this movement "Two Jews: one rich, the other poor." It was inspired by a pair of pictures that Hartmann presented to the composer showing two residents of the Warsaw ghetto, one rich and pompous, the other poor and complaining. Mussorgsky based both themes on incantations he had heard on visits to Jewish synagogues.

The Market at Limoges. A lively sketch of a bustling market, with animated conversations flying among the female vendors.

Catacombs: Cum Mortuis in Lingua Mortua. Hartmann's drawing shows him being led by a guide with a lantern through cavernous underground tombs. The movement's second section is a mysterious transformation of the Promenade theme.

1 | M U S S O R G S K Y P i c t u r e s a t a n E x h i b i t i o n

The Hut on Fowl's Legs (Baba Yaga). Hartmann's sketch is a design for an elaborate clock suggested by Baba Yaga, the fearsome witch of Russian folklore who eats human bones she has ground into paste with her mortar and pestle. She also can fly through the air on her fantastic pestle, and Mussorgsky's music suggests a wild, midnight ride.

The Great Gate of Kiev. Mussorgsky's grand conclusion to his suite was inspired by Hartmann's plan for a gateway for the city of

Kiev in the massive old Russian style crowned with a cupola in the shape of a Slavic warrior's helmet. The majestic music suggests both the imposing bulk of the edifice (never built, incidentally) and a brilliant procession passing through its arches.

The work ends with a heroic statement of the Promenade theme and a jubilant pealing of the great bells of the city.

2 | M U S S O R G S K Y P i c t u r e s a t a n E x h i b i t i o n