the Fall 2015 edition - University of Northern Colorado

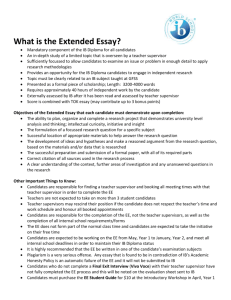

advertisement