Understanding Errors In Organizations: Tensions And Paradoxes

advertisement

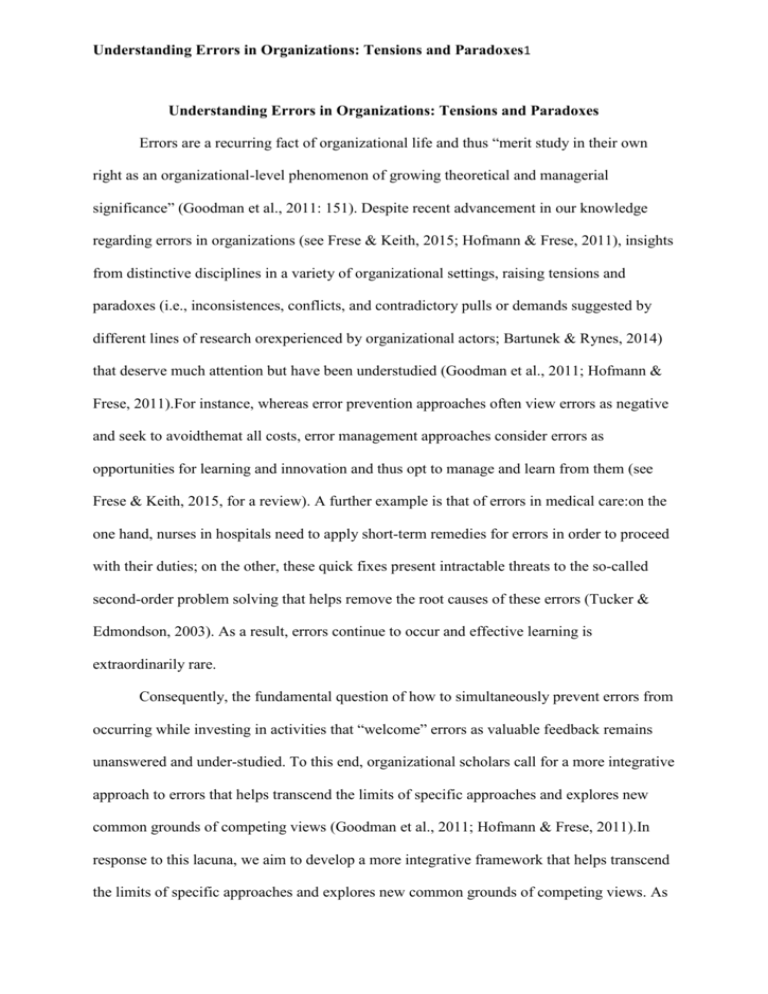

Understanding Errors in Organizations: Tensions and Paradoxes1 Understanding Errors in Organizations: Tensions and Paradoxes Errors are a recurring fact of organizational life and thus “merit study in their own right as an organizational-level phenomenon of growing theoretical and managerial significance” (Goodman et al., 2011: 151). Despite recent advancement in our knowledge regarding errors in organizations (see Frese & Keith, 2015; Hofmann & Frese, 2011), insights from distinctive disciplines in a variety of organizational settings, raising tensions and paradoxes (i.e., inconsistences, conflicts, and contradictory pulls or demands suggested by different lines of research orexperienced by organizational actors; Bartunek & Rynes, 2014) that deserve much attention but have been understudied (Goodman et al., 2011; Hofmann & Frese, 2011).For instance, whereas error prevention approaches often view errors as negative and seek to avoidthemat all costs, error management approaches consider errors as opportunities for learning and innovation and thus opt to manage and learn from them (see Frese & Keith, 2015, for a review). A further example is that of errors in medical care:on the one hand, nurses in hospitals need to apply short-term remedies for errors in order to proceed with their duties; on the other, these quick fixes present intractable threats to the so-called second-order problem solving that helps remove the root causes of these errors (Tucker & Edmondson, 2003). As a result, errors continue to occur and effective learning is extraordinarily rare. Consequently, the fundamental question of how to simultaneously prevent errors from occurring while investing in activities that “welcome” errors as valuable feedback remains unanswered and under-studied. To this end, organizational scholars call for a more integrative approach to errors that helps transcend the limits of specific approaches and explores new common grounds of competing views (Goodman et al., 2011; Hofmann & Frese, 2011).In response to this lacuna, we aim to develop a more integrative framework that helps transcend the limits of specific approaches and explores new common grounds of competing views. As Understanding Errors in Organizations: Tensions and Paradoxes2 such, we focus on idenfying and exploring tensions and paradoxes in error research and practice that may have important consequences on the way organizations cope with errors and have not received much attention. Consistent with organizational scholars (Goodman et al., 2011; Hofmann & Frese, 2011), we define errors as essentially unintended and potentially avoidable deviations from organizationally specified goals and standards that can potentially yield either adverse or positive organizational consequences. To develop our theoretical propositions, we focus on three lenses embedded in error research that result in in conflicting conclusions and practices: namely (1) level of analysis – the degree to which errors are attributed to the individual (e.g., individual employee) or collective actors (e.g., teams, departments, units, organizations); (2) temporal dynamism – the degree to which organizational emphasis is put before, during, and after an error occurs; and (3) priority – the degree to which conflicting priorities (e.g., error management vs.innovation) are assigned to error coping strategies(see Table 1.). The level of analysis perspective centers on tensions and paradoxesrooted in the opposite influence of individual and collective antecedents on individual and collective errors. For example, while team climate of "no blame and no punishment" encourages open communication and associated with lower collective errors occurrence (Edmondson & Lei, 2014; van Dyck, Frese, Baer, & Sonnentag,2005), in some cases, it may also increase individual errors occurrence by reducing personal accountably for mistakes (Mero, Guidice, & Werner, 2014). Vice versa, individual rule adherence that is associated with lower individual error occurrence, when too rigid and dogmatic, might resulted in less communication and interactions with other organizational actors and increase collective errors (Bell & Kozlowski, 2011). Regarding the temporal aspects of errors, an event time frame and timing of error responseshave informed our assessment of the error literature. For example, the partition time Understanding Errors in Organizations: Tensions and Paradoxes3 frame categorizes the error process as before, during, and after the occurrence of error-linked adverse outcomes (Frese & Keith, 2015; Goodman et al., 2011). Along this partition dimension, organizations often use error prevention strategies to guard against errors from occurring during the “before” phase and enact error management strategies to block negative error consequences once (i.e., “during” and “after”) an error has occurred (Hofmann & Frese, 2011). Different error strategies thus present a tradeoff issue: whereas error prevention emphasizes routine, standardization, and control (Wildavsky, 1991), error management encourages exactly the opposite - adaptation, flexibility, and experimentation (Frese & Keith, 2015). We also explore the tensions and paradoxes caused by competing priorities, operating simultaneously in organizations. For instance, the tension between error free performance and innovation. Under pressure of precision, reliability and comprehensive fact-based problem solving errors are not acceptable, organizations thus find it conflicting to simultaneously pursue innovation which constantly incur trials-and-errors and thus temporarily increase economic costs (Grote, 2009), decrease customer satisfaction, or even cause injury and loss of human lives (Naveh & Erez, 2004). At its core, this paper pays attention to the tensions that are integral to complex organizational systems and that span the level of analysis, temporal dynamism, and priority perspectives. In doing so, our work offers opportunities to take a more holistic and integrative approach to errors that helps to unify existing error literature and guide future research to resolve and transcend the existinginconsistencies and contradictions (see Table1.).We hope that our work suggests ways to understand the current state of error research andset helpful directions for future research that will fully explore the opportunities that assist organizations to operate as error free zones. Understanding Errors in Organizations: Tensions and Paradoxes4 References Bartunek, J. M., & Rynes, S. L. (2014). Academics and practitioners are alike and unlike the paradoxes of academic–practitioner relationships. Journal of Management, 40: 11811201. Bell, B. S., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2011). Collective failure: the emergence, consequences, and management of errors in teams. In D. A. Hofmann & M. Frese (Eds.), Errors in organizations: 1-44. New York: Taylor & Francis Group. Edmondson, A., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1: 23-43. Frese, M., & Keith, N. (2015). Action errors, error management and learning in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 66: 21.1-21.7. Goodman, P. S., Ramanujam, R., Carroll, J. S., Edmondson, A. C., Hofmann, D. A., & Sutcliffe, K. M. (2011). Organizational errors: Directions for future research. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31: 151-176. Grote, G. (2009). Management of uncertainty: theory and application in the design of systems and organizations. London: Springer-Verlag. Hofmann, D. A., & Frese, M. (2011). Errors, error taxonomies, error prevention, and error management: Laying the groundwork for discussing errors in organizations. In D.A. Hofmann & M. Frese (Eds.), Errors in organizations:1-44. New York: Taylor & Francis Group. Mero, N. P., Guidice, R. M., & Werner, S. (2014). A field study of the antecedents and performance consequences of perceived accountability. Journal of Management, 40: 1627-1653. Naveh, E., & Erez, M. (2004). Innovation and attention to detail in the quality improvement paradigm. Management Science, 50: 1576-1586. Tucker, A. L., & Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Why hospitals don’t learn from failures: Organizational and psychological dynamics that inhibit system change. California Management Review,45: 55-72. van Dyck, C., Frese, M., Baer, M., & Sonnentag, S.( 2005). Organizational error management culture and its impact on performance: A two-study replication. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90: 1228-1240. Wildavsky, A. (1991). Searching for safety. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. 5 Errors in Organizations: An Integrative Review Table1. Summary of Research Findings, Tensions and Paradoxes, and Related Future Research Recommendations Review Lens Level of analysis Findings Team Errors Team errors occur as a result of the joint effects of antecedences across individual and team levels. Organizational and System Errors Organizational culture (e.g., error management, safety) is pivotal in reducing negative error consequences and promoting positive error consequences (e.g., learning and innovation). Temporal Dynamism Priority An Event Time Frame The development of effective error strategies is partitioned into three phases as before, during, and after the occurrence of an error. In the “before” phase, prevention strategies are used to defend against errors. In the “during” phase, error management strategies are enacted, while in the “after” phase, error management shifts attention to learning, sustainable performance, and innovation. Timing of Error Responses The timing of error responses has dramatic effects on organizational performance and outcomes. Errors should be identified and reported sooner rather than later. Once errors are clearly declared, organizational actors are under extreme time pressure and must formulate interpretations and make correction choices quickly. Studies demonstrate how different rates of taking action generate qualitatively different error dynamics and outcomes. Error Management and Innovation Innovation is inherently susceptible to errors and even increases the occurrence of errors. However, a complementary perspective suggests that innovation may also eliminate errors. Tensions and Paradoxes Future Research Individual antecedents may interact with team antecedents in a same or an opposite direction to affect team errors. The influences of defense activities required to eliminate errors at one level may have an opposite effects on error occurrence on another level. Explore the tension occurring across levels of analysis. Leverage the unique opportunities and tensions of different error forces across levels and develop new theoretical models and new insights that reflect the reality of error situations, especially regarding the complex components. Whereas error prevention emphasizes precaution and ex ante actions and works through routines, standardization, and control, error management focuses on ex-post, real-time actions, and encourages adaptation, learning, and flexibility. Take a complementary view and investigate the extent to which different error strategies along the timeline might help or hinder learning from errors; and under what conditions. Either too slow or too fast error responses can generate more errors. Whereas short-term, heroic quick fixes may remove the problems at hand, they cannot remove root causes that may be triggered to cause more errors over time. Priority assigned to error elimination and to other organizational goals (e.g., innovation) may lead to conflicting activities. Explore the role of the timing of error responses and examine the factors that influence the tradeoff and timing alignment between different organizational agents and their error strategies in changing error situations. Adopt the paradox paradigm to explore how to benefit from the influence of multiple contradicting priorities and synergize them.