Options Analysis Model

advertisement

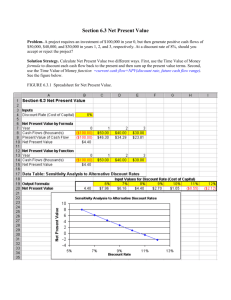

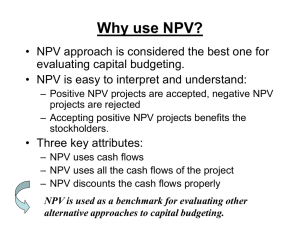

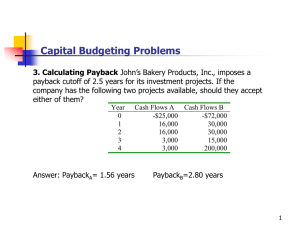

[Agency Logo] [Agency Title] [Investment Proposal Title] Options Analysis [Date] Approval Name/Title Signature Date Senior Asset Investment Planner Analyst Name/Title Email Phone Version Control Version Draft 1 Draft 2 Final Date Status/Action/Change Approved By Executive Summary Short List The final results of the options analysis are presented in clear, concise terms that justify the recommended and alternative options, and the exclusion of other feasible options from the short list. The results are summarised in a way that clearly displays the underpinning logic and assumptions. Diagram 1 below provides an example, based on a fictitious business case for the delivery of improved hospital services. Diagram 1: Options Analysis – Results Summary Short List Options Reasons for Inclusion/Ranking Status Quo: Current Hospital at location A Base case Option Two: Refurbish Moderate social impact / benefit Moderate service delivery improvement Within agency and State budgets, (including recurrent costs) Option Three: Refurbish, plus out-sourced community care Stronger social impact / benefit Affordable Faster service delivery start Option Four: New Hospital at location B, plus community care High social impact / benefit Beyond State and agency budgets Private finance likely Long List Reasons for Exclusion Option Five: New hospitals in locations B and C High service delivery impact But beyond demand scope for the next 10 years in those locations Well beyond State budget and agency capacity 1 The final list of options is not extensive. It focuses on the top three to four highest priority options, plus the highest ranking ones that failed to make the short list. The key points that are clarified include: which is the recommended, value-for-money option in the short list, and why, despite its weaknesses; which short-listed options present the best alternatives, if decision-makers wish to take a less risky or less costly approach; the strengths and weaknesses of each option, including those excluded from the short list; and why the excluded options were rejected (for example, due to excess or inadequate scope, affordability, or relatively low social benefit and service delivery improvement). As depicted in the following diagram, reviewers in both an agency and Treasury should also be able to understand easily how the options analysis results relate to the main points of advice in the ACA or business case. Diagram 2: Options Analysis – Input Options Analysis ACA/Business Case Advice Strategic Justification Options Short List Investment Scope VFM Comparison Short-listing Scope Social Impact Benefits Agency Financial Cost Agency Performance Schedule Economic Risk Strategic Justification This section anchors the options analysis to the justification for an investment proposal, as expressed in the service delivery objectives and model, and the prioritised list of investments in the strategic asset plan. The options analysis should take as its point of reference a particular, high priority investment proposal listed at the conclusion of the agency’s strategic asset plan. 2 There is no analytical work required at this stage. The purpose is to confirm that the justification for the investment proposal has been established in the strategic asset plan before proceeding to the options analysis. Investment Scope This section clarifies the scope of the investment proposal, particularly the primary functions that will be enabled by the asset. Concise articulation of the primary functions is critical in demonstrating what the asset components must do to achieve the State’s service delivery objectives and practical results from the perspective of the community members who will benefit from the operation of the asset. Value management is one technique that can be used to clarify the functional requirements and to establish a coherent scope for the investment proposal before proceeding to the next phase of the analysis. Further information is in the SAMF Value Management module. Functions The analysis assesses how a function could be achieved at the most efficient level of quality and cost, including whether the initial proposal should be reconfigured, scaled back, relocated or even avoided. The scope analysis results in documented: evaluation of the functional scope against strategic business and service delivery plans; prioritisation of project objectives and functions; an action plan for the next phases of the analysis. Key questions include: what are the expectations of likely service recipients? what are the quality standards, both mandatory and comparable from relevant projects (e.g. square metres per office worker)? how will the achievement of the benefits be measured over time? Completion of this section provides a foundation for the comparison of the options to follow. An agency therefore develops the scope and functions to a level of detail that will allow each option to be compared, and to clarify the difference an option would be expected to make. 3 Investment Options – Long List This section identifies the full range of feasible options to deliver the service delivery objectives targeted by the investment, based on the functional scope. The emphasis is on sorting the feasible from any academic options – for example any that would rely on unproven technology that would not be available and reliable for some time after the service delivery start date identified in an agency’s strategic asset plan. While emerging options are monitored, the allocation of significant time and resources to their analysis is not appropriate. The appraisal of a single type of investment option is not sufficient. Instead, a range of options is identified which covers a mix of existing asset optimisation, non-asset initiatives and varying levels of new minor or major capital expenditure. Within that range, alternatives are explored (for example, the construction of a new building versus an office lease). Status Quo The status quo (or base case option) must be included as the first item in the long list. This should clarify whether the objectives of the investment proposal could be achieved with existing assets and non-asset initiatives, if there was no new investment. The status quo option must be realistic. An assessment is provided of the impact, costs, benefits and financial implications associated with continuing the current circumstances. In the absence of compelling consequences, analysed objectively, the status quo may prove to be the best value for money option, at least in the short to medium term, particularly when funding is tight. If not, the status quo option provides a basis against which other options can be compared. Alternative Options The following list of questions may be useful when identifying alternative options: 4 Are different sizes or quality of operation possible? For example, could the current operation be scaled down, or is asset replacement justified? What is the sensitivity of demand to the level and structure of pricing? Would varying the pricing structure be a realistic alternative to increased investment? What is the effect of varying the design life or timing of the option? What alternative locations are possible? Are there potential trade-offs between (say) labour and capital, or capital and maintenance costs? Would better staff training reduce personnel requirements and the pressure for asset investment? Are all elements of the operation equally justified? Could the operation be combined with another, or divided into parts, to advantage? Can economies of scale be achieved? Are there opportunities for integration with other services (for example, through multi-purpose assets or facilities)? Addressing these questions may also prompt some re-definition of the original objectives for the investment proposal. If this is the case, early advice is provided to investment decision-makers, rather than wait until the final options analysis document is completed. Apply Key Filters To assist in the generation of options for the long list, and to help identify the feasible ones, three filters are applied: timing variations; economic conditions; scale and cost. Timing It is important to consider variations to the timing of the investment proposal, and of the options, including by making them contingent upon a related event. The premature development of a project may lead to excess capacity, shorter effective asset lives and higher financing costs. The timing of an option can also have a crucial impact on whether an investment achieves its stated outcomes. The timing filter can therefore be used to mitigate the risks of an option and to optimise its social, financial and economic returns. Variations to timing are made with regard to aspects including: matching demand with supply; the ability to employ temporary measures to delay the timing; likely technological advances over the interim period; 5 the time pattern of asset construction and replacement costs; cyclical conditions that impact on the proposal, whether economic or industry-specific; and phasing development to minimise risks and under-utilisation of the asset. Phased development can be more expensive, but may provide the flexibility to: achieve a balance between higher construction costs and the opportunity to adopt new technology; and coincide with a projected growth or decline in demand, or movements in the business cycle. Economic Conditions Significant proposals should be aligned with projected economic conditions. The purpose of applying this filter is to determine the impact that economic trends may have on the option in terms of its ability to achieve the objectives of the investment proposal. The assessment of economic conditions helps to identify key uncertainties and risks and the optimal timing for the investment. Commercially-oriented proposals require a greater level of investigation than others. An ancillary step is the establishment of strategies for monitoring and reviewing the implementation of an option. This entails defining and timetabling key milestones and planned achievements. The economic conditions filter is also important in building a sense of reality into the sequencing of the various investment proposals in an agency’s Asset Investment Plan, as well as ensuring that sufficient capacity exists in an agency and the broader economy to deliver the option. Further guidance is in the SAMF module on Asset Investment Planning. Scale and Cost Filtering potential options in terms of their overall scale and estimated cost is also useful. For example, a minimum investment option would be one that involved the level of funding and effort required to meet only the most urgent, highest priority objectives and functions needed to achieve improved service delivery beyond the status quo. Following on from the minimum option (which may, for example, have an estimated total cost of $10 million), further options could be developed at the total cost of say $15 million and $20 million, at the moderate and maximum investment levels, respectively. 6 The scale and cost filter has the advantage of putting the options analyst in the mindset of the investment decision-maker, who will seek to understand the extra value for money that would be achieved from the higher levels of expenditure needed for each option beyond the status quo. If approached objectively, the filtering of options by scale and cost should help to broaden the focus beyond a particular asset solution, and increase the use of cost-effective non-asset initiatives within each investment threshold. By making the potential service delivery increments and costs between options transparent, an analyst demonstrates the willingness to participate in the real world of investment trade-offs faced by decision-makers – which in turn enables progress on other worthy proposals from within an agency, or from other agencies. In that context, an agency is more likely to achieve approval for a manageable increase in investment funding that enables some practical service delivery – rather than place all faith in a high cost option that is worthwhile, but will still fail to gain approval due to funding constraints. Investment Options – Short List This section provides concise information that summarises the logic and reasons both for the creation of the short list and for the prioritisation of options within it. Once the long list of feasible options is clear, a comparative analysis of the options is conducted from four perspectives, namely: the social impact; effect on an agency’s performance and financial position; and the economic costs and benefits to the community. For example, an option may be dismissed objectively because its social impact would be clearly inferior, it would be unaffordable and because the economic benefits would be marginal, at high cost. These failings can be seen, and a short list of options finalised, through objective analysis. Perspective One: Social Impact This section identifies the sectors of the community that would gain and those, if any, that would lose, should an option proceed. An agency considers the social costs and benefits of an option, in the context of the Government’s policies and objectives. Categories of social impact include health and safety, law and order, the environment and indigenous communities. 7 The qualitative social benefits, costs and risks associated with the option are outlined. The significance of the impact is appraised with reference to various indicators. This ensures that qualitative impacts are considered systematically, along with the quantitative results from the financial and economic analysis that follows later. There are three broad steps in social impact analysis: 1. define the scope of the analysis; 2. identify the categories of impact; and 3. analyse the significance of each impact. Step One: Define the Scope of the Analysis Investment options may cause a change in the relationships, institutions, resources or environment in society, thereby affecting the desirability of an option. These changes are the focus of social impact analysis. Discretion is exercised in deciding what constitutes a social impact. A consistent approach is taken on the degree to which indirect costs and benefits are included. For example, it would be imprecise to include a broad range of indirect benefits, yet not include the associated indirect costs. The analysis is subject to two main conditions: the issues should not be quantifiable, and hence the subject of financial or economic analysis; and the impact must be clearly attributable to the option. Step Two: Identify the Categories of Impact Objectively-selected impact categories assist in identifying and organising the social impacts that would arise from each option. The most common social impact categories are: 8 health and safety; quality of life; State development goals; environment and heritage; sustainability; indigenous communities; law and order; and intangible economic (such as business confidence). Step Three: Analyse the Significance of Each Impact Due to the difficulties of placing monetary values on the impact categories, the analysis attempts to gain a full understanding of the social ramifications of an option by assessing the degree of potential significance to the community. For example, each social impact is assessed in terms of: whether the impact is isolated, localised or far-reaching; the expected duration, timing and spread of the impact; whether specific groups in the community and/or industry would be affected, either positively or adversely, and the extent of the impact on these groups; and the level of political sensitivity and public interest. Community consultation is undertaken, as appropriate, to help identify and analyse the significance of social impacts, particularly when the analysis is done in support of a business case. Community consultation is undertaken in part to help manage expectations of what is possible and affordable for the Government. Perspective Two: Agency Financial Evaluation This section identifies the revenues and expenditures that will be created by each option, and establishes the net cash impact on the financial position of the agency. An essential element of the analysis is to demonstrate the expected financial viability and budgetary impact of each option. For options of a commercial nature, this involves estimating the return on investment and profitability. For non-commercial options, this involves defining the most efficient way to deliver the desired service delivery strategies. Financial evaluation is conducted using discounted cash flow analysis. Based strictly on the cash flow for an option, the analysis recognises several important features: an amount of money, even when adjusted for inflation, is worth more now than it is in the future. This is termed the time preference of money; resources used by one option could be allocated elsewhere and cannot be used twice. This is termed the opportunity cost; and 9 the cash flow for an option is often uncertain and subject to risk. The time preference of money, and the opportunity cost and risks, can be accounted for by discounting future cash flows by an appropriate rate. The financial evaluation of each option is conducted using the following six steps: 1. state the key factors, assumptions and relationships; 2. identify cash flows; 3. select an appropriate discount rate; 4. calculate financial performance measures; 5. clarify the budgetary implications; and 6. conduct sensitivity and scenario analysis. Step 1: State the Key Factors and Relationships All key factors, assumptions and relationships are stated clearly at the outset. Factors to be estimated may include the following: growth in demand; timing; adoption of technology or services; population growth; inflation; exchange rates; commodity prices; unemployment rates; key input prices and costs, and output prices and revenues; proceeds from any land sales or rezoning applications; and competition from other output providers. A consistent approach is used in setting the key factors to ensure that the results for different options are comparable. The impact of the key assumptions on the results of the financial evaluation is also clarified. 10 There are a number of sources of macroeconomic data and forecasts at the Federal, State and industry levels that should be used to address each factor. However, in some circumstances, it may be more appropriate for particular factors to be estimated at the agency level. The scale of the investment proposal will have a significant bearing on the extent of data collection and the depth of analysis required. Before determining the extent of the required data collection, careful consideration is given to the interaction between the factors being examined. Analysis of the relationship between the key factors and the objectives of an option can also highlight variables for sensitivity testing. Step 2: Identify Cash Flows Cash flow analysis is the basic building block of financial evaluation. The analysis identifies all incremental cash flows that would accrue to, or be incurred by, the agency as a direct result of the option. This involves determining the capital costs, residual values, and the annual operating costs and revenues. Other key issues include the treatment of inflation, avoiding double counting, and determining the appropriate timeframe. The quality and reliability of the analysis will depend on the: accuracy of the estimates on which the cash flows are based; identification of all relevant cash flows; and exclusion of all non-cash items. Cash Flow Aspects There are five aspects that are considered when identifying cash flows: incremental analysis: where incremental revenues and costs are weighted by an appropriate probability, and then discounted with the risk-weighted discount rates to generate weighted, average expected cash flows; opportunity costs: in terms of the return of the next best alternative that would be foregone as a result of proceeding with the option; accounting practice: in terms of recording actual cash movements; inclusion of all incidental effects: such as corporate overheads; and sunk costs: that have already occurred and are irreversible. 11 Other issues that are considered are the: timeframe being considered in the analysis. In most cases, the timeframe equates to the life expectancy of the option’s major asset or assets. However, if any material benefits or costs are expected to continue flowing beyond the life of an asset, and it is not expected to be replaced, it may be prudent to extend the timeframe for the evaluation; treatment of inflation – in terms of representing cash flows in real or nominal, inflation-adjusted terms (as a rule, the real approach is simpler, although there are circumstances in which it is more appropriate to use the nominal method); relevant resource cost categories – such as labour, materials, fuel and energy, overheads, transportation and travel, including any significant cost-generating activity components; and the residual values – to represent the net revenue or costs of winding up the asset at the end of its life, using methods such as depreciated replacement value, escalated value, market value or net present value (in perpetuity or other method). Life Cycle Cost The full life cycle cost of the option should be considered when identifying the cash flow. For this, an agency should identify the total cost of the option throughout its life, including for planning, design, acquisition and support, and any other costs directly attributable to the option. Particular capital and ongoing operational and maintenance costs that should be identified include: capital costs: all up-front development expenditures required to achieve the forecast benefits, such as the acquisition of land, construction costs, furniture and fittings, equipment purchases, legal and consulting fees, contingencies and working capital, and the residual value and costs of disposal at the end of the option’s life; and operating cash flows: in terms of the recurrent operational, maintenance and refurbishment implications, which can be significantly higher than the initial capital costs, over the life of the option. Common Mistakes Some common mistakes in the identification of cash flows for financial evaluation are listed below: 12 the interest costs of debt finance should not be included in the cash flow, except where direct fees are payable to financiers to set up loans; expected revenues should be calculated, based on average expectations, and not arbitrarily reduced to take account of uncertainty; depreciation costs should not be included in the cash flow; in terms of escalation, costs should not be inflated when the analysis is being conducted in real terms; and conversely, applying a nominal discount rate to real cash flows is incorrect. Further guidance is available in the Australian Standard on Life Cycle Costing – An Application Guide (AS/NZS 4536:1999). Step 3: Select an Appropriate Discount Rate Many financial evaluation measures require the use of a risk-adjusted discount rate to determine the viability of an investment. The discount rate is therefore one of the key factors in determining the financial feasibility of an option. In basic terms, the discount rate has two components: the cost of funds: the 10 year borrowing rate from the Western Australian Treasury Corporation (WATC) is used as a proxy for the risk-free rate; and a premium to allow for risk (based on industry norms) is added to the risk-free rate. In terms of selecting an appropriate discount rate for most investment proposals, Treasury prefers that summary results are presented using a range of rates, namely 4%, 7% and 10%. This approach is consistent with the majority of national and State guidelines. However, the best way to establish the appropriate discount rate for a particular proposal is to contact Treasury (and the WATC for complex proposals) before the options analysis begins. This is because in practice, no single discount rate can be prescribed for all types of investment proposal. Instead, the rate will depend on factors including project risk and duration, and whether a social or economic asset is involved. Step 4: Calculate Financial Evaluation Measures The financial evaluation is completed by calculating financial performance measures that address the key factors, cash flows and the selected discount rate. Up to three methods are used, where appropriate for the analysis of particular options (as distinct from comparisons between them): Net Present Value (NPV); Internal Rate of Return (IRR); and Discounted Payback Period (DPP). Treasury can provide advice on the advantages and disadvantages of the various financial evaluation measures, and how to apply them. 13 Net Present Value (NPV) The NPV of an option reflects its added value or profitability, after adjusting for the timing of revenue and cash flows by the appropriate discount rate. The NPV method is appropriate for both financial and economic evaluations and, therefore, applicable to all options with financial or social benefits. For options of a commercial nature, the NPV reflects financial viability, as the NPV rule for commercial decision-makers is to favour proposals with an NPV greater than zero. For proposals delivering social benefits that are not easily quantified, NPV provides a clear exposition of the cost of each alternative option. NPV is a useful measure for deciding whether an option is viable or not, but is not useful in making choices between options unless accompanied by other measures (such as IRR and Benefit Cost Ratio) and calculated with reference to economic as well as financial parameters. Internal Rate of Return (IRR) – Limited Application The IRR represents numerically the discount rate at which the NPV is zero. It can be useful in ranking investment options. The IRR demonstrates the option’s return or profitability in percentage terms, overcoming the NPV presentation problem, where a dollar figure is presented that may be misunderstood. In the context of IRR, the discount rate is often called the hurdle rate, as it represents a hurdle that an option must reach in order to proceed. Therefore, in the absence of capital constraints, commercial decision-makers accept all options that have an IRR greater than the discount rate. Discounted Payback Period (DPP) – Limited Application For long-term investment options, DPP is useful when estimating how long it will take before an option breaks even and generates a return. However, this method is only useful as a general guide to the financial risks attached to each option. The major drawback of the DPP measure is that it ignores all cash flows after the investment is recouped. As a result, it has a bias against options with long lead times or high pay-offs late in their life cycle. For this reason, DPP is only used in conjunction with the NPV and IRR measures. Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) This measure is a derivation of the NPV formula, represented as a ratio of the present value of revenue (or benefits including economic benefits) to the present value of costs. 14 The BCR measure is not favoured in financial analysis, because it gives the same answer as the NPV formula, where the threshold rule that NPV must be greater than zero is applied. However, the BCR is useful in setting and assessing resource priorities within an agency, when competing options have a range of sizes and have different economic outcomes. Step 5: Identify Budgetary Implications The financial evaluation report includes two cash flow models to: illustrate the value for money from each option; and demonstrate the budgetary implications and the impact on the Government’s financial targets. Assessment of Value for Money Value for money is examined for each of the options, including the status quo. The rigour and results of the financial evaluation have a significant influence on the relative rating and priority given to options, where those with stronger cases for investment, with demonstrably higher benefits and lesser costs, will tend to be favoured over weaker options. In this context, options that have been poorly evaluated, and that offer little confidence in the benefits identified, will be allocated lower priority. Demonstrate the Budgetary Implications Not all approved projects are funded from the Government’s Consolidated Account. Examples of other potential funding sources are the Commonwealth, borrowings, asset sales, internal agency funds and private sector contributions. An agency should demonstrate how the option is proposed to be funded, and, in particular, the implications for the Consolidated Account. Each option is assessed in terms of the impact on the Government’s financial targets, such as the general government operating balance, net debt and general government expenses. Both recurrent and capital implications are identified. This involves adjusting the cash flow model as follows: adjusting all real cash flows to include inflation; removing any cash flows related to private sector financing; truncating the reporting period to reflect the relevant budget period; adding the proposed financing cash flows (such as the interest and principal cash flows); and incorporating depreciation over the useful life of the assets. 15 Other implications are considered including whether: any State taxation revenue will accrue to the Consolidated Account and not to the agency; and whether the option would affect the cash flows of other general government agencies. Agencies should consult Treasury when estimating these impacts. Step 6: Sensitivity Analysis This technique enables analysts to examine how sensitive the potential outcomes of an option are to the underpinning assumptions. This enables explicit recognition of the uncertainty regarding the investment outcomes. Sensitivity analysis is a key tool to identify the significant risks to the estimated cash flows. Even a simple table, illustrating the impact of changing the key variables on the estimated cash flows, can be of great benefit. Sensitivity analysis seeks to: identify the main variables that have a material impact on the option, so that they can be managed and risks minimised; determine when more information is needed, in order to improve the assumptions; identify the consequences of inaccurate estimates of variables; and expose inappropriate forecasts. There is a wide range of methods than can be used to conduct sensitivity analysis. The following are some of the commonly-used approaches: 16 Scenario Analysis: where plausible combinations of key assumptions that may occur under different outcomes are tested. Scenario analysis does not require special techniques or spreadsheet tools. It is merely a way of thinking about investment outcomes and modelling these combinations accordingly. Data tables can be useful for this analysis. Single-Variable Sensitivity Testing: where each variable that is likely to have a material impact on the proposal, and whose forecast is uncertain, can be varied (one at a time) across a range of likely outcomes. Spider Diagrams: which show the effects of uncertainty on more than one variable at a time. Break-Even Analysis: similar to sensitivity testing, which tests uncertainty in key variables in order to address the question ‘how bad do things have to get before the option would lose money?’ Monte Carlo Simulation: a tool for considering the entire distribution, and all possible combinations, of outcomes – which requires input of the full range of quantified outcomes for each variable and their associated probabilities. Perspective Three: Agency Performance Evaluation This section assesses and quantifies the direct impact of an option on the agency’s ability to meet its objectives, and to deliver its services as articulated in its strategic asset plan. Performance evaluation enables an agency to assess, prioritise and seek funding for an option, based on its impact on the outcomes desired by Government. The anticipated impact of the option should be measurable and quantified using appropriate and relevant performance indicators. Performance evaluation entails the following three steps: 1. identify the agency-level services and outcomes affected; 2. quantify the impact of the option on agency effectiveness; and 3. quantify the impact of the option on agency efficiency. Inclusion of the status quo option enables the impact of the alternatives to be contrasted against the current state of affairs. Step One: Identify the Agency Outcomes and Services The first step in the performance evaluation identifies which of the agency’s desired outcomes and services will be affected materially by an option’s service delivery approach. In the case of agencies with more than one service, the analysis should clarify which services are affected, which are excluded, and why. In some cases, the service delivery strategies and functions may concern a work area or branch that contributes in only a minor way to the overall measure of the agency’s services. In these cases, the results of the option, which may be significant to the branch, are often ‘swamped’ by the agency’s aggregate services. For these, it would be useful to present the impact of the option on the services of the branch, as well as at a whole-of-agency level. It is possible that the option may affect the relationship between the desired outcomes and services. To the extent that this was not examined in the Strategic Justification section of the options analysis above, it should be detailed here. In addition, the potential impact of the option on the business deliverables of other agencies or Government as a whole are considered, in consultation with relevant agencies and Treasury. 17 Step Two: Quantify the Impact on Agency Effectiveness Agency performance may be measured by the effectiveness of an option in achieving desired outcomes, in terms such as quality or timeliness. Agencies therefore identify milestones or significant events that may be used to indicate progress towards achieving the outcomes; noting that there may be time lags between the introduction of initiatives and the results. Effectiveness is often measured through satisfaction surveys. To determine the impact of an option on desired outcomes, stakeholders are consulted, including service recipients, employees or other government agencies. Consultation provides a good way of involving relevant parties in the development of options from an early stage, while managing expectations. The effectiveness of an option in achieving desired outcomes may also be assessed in quantitative terms, such as reduced waiting times, increased patronage or decreased work-related injuries. For example, an agency may be considering updating computer systems used at branches that serve the public. Unit costs are likely to rise, but the quality of services (as determined by customer surveys) should be enhanced, and the time taken to serve customers improved. Step Three: Quantify the Impact on Agency Efficiency Many options aim to expand the quantity of services delivered. As a general rule, performance evaluation allows an agency to demonstrate how different options will affect the cost efficiency with which services are delivered. The most commonly used measure of cost efficiency is unit cost, which is defined as the total cost of service divided by the total quantity of service delivered. Examples include cost per student, cost per licence issued and cost per public transport passenger. The information required for the assessment of unit costs will generally flow from the Agency Financial Evaluation above. In addition to unit costs, the efficiency of an option may be assessed in terms of improved service quality or timeliness (for a given cost). Depending on the circumstances, it may be appropriate to use indicators of productivity that relate physical inputs to physical outputs, such as units of output per machine hour, or number of phone enquiries handled per hour. 18 Perspective Four: Economic Evaluation This section identifies the quantifiable benefits and costs that are expected to result for the community. Economic evaluation addresses the basic question: what is the option worth to the general community? The aim of economic evaluation is to compare the quantifiable benefits that would accrue as a result of an option, with the costs of finance and other resources devoted towards the option (such as the labour employed). These costs are known as the opportunity cost of government funds and resources. The results identified must be tangible and occur as a direct result of the investment. As the benefits of many public sector investments cannot be recouped by the Government, a robust options analysis must incorporate some measure of wider economic (or other) benefit, in order to determine which option to choose, and whether or not to proceed. It is essential that standards of objectivity, transparency and rigour be adopted when a public benefit test is conducted. The complexity of the analysis will depend on the difficulty of measuring the external benefits and costs associated with the option, and the scope and risks involved. Cost Benefit Analysis Cost benefit analysis is the most commonly used, and most comprehensive, of the economic evaluation techniques. Following essentially the same approach as the agency financial evaluation, cost benefit analysis assesses, on a present value basis, whether the benefits exceed the costs of the option, and that no other allocation of resources would generate higher net benefits. Cost benefit analysis can be applied to most, if not all, options that involve costs with revenues and/or other tangible and measurable services. Quantifying external effects, in monetary terms, can require considerable information that is not always readily available by direct means. Depending on the size, significance and risk of the option, the analysis may be scaled back to a quantification of the major costs and benefits, and the external factors to be identified. The main steps in economic evaluation are: 1. focus on the objective of the option and define the measures against which it, or its alternatives, will be judged; 19 2. assess the value of the benefits and costs; 3. discount the costs and benefits to present values; 4. compare the discounted benefits against the discounted costs; and 5. test the sensitivity of the results. Step 1: Focus on the Objective The evaluation of an option, or the comparison of options, is impossible unless the analyst knows the objective of the investment. This should have been clearly defined as part of the Strategic Justification stage of the options analysis above. In an economic evaluation, costs and benefits are measured in terms of the economy as a whole, regardless of who the net benefits accrue to (as opposed to a financial evaluation which is performed from the agency’s perspective). Initially, objectives are defined in terms of the market failure or market imperfections that could warrant Government intervention. In addition, care is taken to ensure the objectives are specific enough so that it is not difficult to establish subsequently whether, or to what extent, they have been met. If the option involves a request for new funding, or the analysis involves comparing alternatives that have different costs, then the costs and benefits must be measured in a form that can be compared against any other option that could be undertaken by the public sector. This usually means that the outcomes from the option are converted into monetary terms. Step 2: Identify and Value the Costs and Benefits Government investments often involve a diverse range of objectives. The revenues and costs incurred directly by the Government are identified in the agency financial evaluation above, and are included in the economic evaluation. All relevant costs and benefits are included. Wherever possible, the direct impact on the revenues and costs to the private sector and individuals, public good benefits, and the indirect (but quantifiable) impacts of positive and negative ‘externalities’ need to be identified appropriately and compared using a common measure, preferably dollars. An externality is a side effect, which can be positive or negative, accruing from an activity that impacts on someone other than those undertaking the activity. An example of a negative externality is pollution from a manufacturing plant that affects adversely the health of residents near the plant. Cost benefit analysis is based on resource costs that are not always reflected by the financial cost. As the market price of resources does not always reflect the true costs to the economy of these resources, when market prices are used, care must be taken to ensure that the price reflects the gains and losses attributable to the economy as a whole, rather than to individuals or groups. 20 In some cases it is not possible to quantify and value certain benefits and costs in dollars meaningfully. Such non-quantifiable variables should still be included in the evaluation with appropriate descriptive information, so that they can be considered with the quantifiable variables during the decision making process. The following are examples of typical benefits and costs: Benefits health, environmental and other social benefits; user benefits; productivity enhancements; savings between options (e.g. differences in operating costs); residual/salvage values; increases in land values; and avoided costs – which would have been incurred under the status quo option. Costs capital expenditure; operating expenditure; maintenance costs; labour costs; research, design and development costs; opportunity costs associated with using land/facilities already in the public domain; environmental costs such as carbon emissions and noise pollution; materials, supplies, utilities and other services; user costs; and safety and risk costs. 21 The value of these benefits and costs is discounted back to their present values in order to generate the NPV for an option. It is therefore important to give careful consideration to the rate at which each benefit and cost would be introduced to the economy after the proposed investment starts to deliver services. This can be simulated in the cash flow, and can significantly alter the relative net present values of alternative options. It can also have a substantial effect on the NPV and other project summary measures. Step 3: Discount the Benefits and the Costs As in the agency financial analysis, the flow of costs and benefits from the option over time is discounted back to present day values. This reflects the fact that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow. In doing so, care is taken to ensure that nominal and real (inflation adjusted) values are not confused, and that the discount rate reflects the choice of nominal or real values. Step 4: Compare the Discounted Benefits and Costs The discounted benefits and costs should be combined to produce the following summary measures: Net Present Value: the sum of the discounted benefits, less the discounted costs of an option; Benefit Cost Ratio: the ratio of the present value of benefits to the present value of costs; and Internal Rate of Return: the discount rate which equates the present value of benefits with the present value of the costs. An investment option is expected to generate a net benefit if its NPV is positive (greater than zero). Similarly, if the option’s BCR is greater than one it will indicate a net benefit, as will an IRR greater than the selected discount rate. (See the above section on Agency Financial Evaluation, Step 3: Select an Appropriate Discount Rate). In pure economic terms, any option with an NPV greater than zero or BCR greater than one is worthwhile and should be undertaken. However, Budget constraints often mean that the Government does not have the capacity to undertake all such proposals. Hence, proposals and options must be compared and prioritised. When comparing options, NPVs are not appropriate, as they will be influenced by the size (scope) of the option. Therefore BCR is the most appropriate summary variable to consider. Options with the greatest BCR should be favoured (if economic factors are the sole criteria for the decision). 22 Step 5: Sensitivity Analysis In any cost benefit analysis, there is usually some degree of uncertainty involved. It is therefore important to examine how changes in key assumptions and variables affect the benefits and costs of an investment option. Typically there are four sources of uncertainty that may require sensitivity analysis: capital costs; construction duration and therefore opening date; operating (including maintenance) costs; and under and over estimation of the benefits. Sensitivity analysis should be conducted using the approach described in Step 5 of the Agency Financial Evaluation above. Multiplier Effects? Any expenditure by Government will produce flow on effects to the economy. Consequently, some cost benefit analyses include measures of the flow on benefits, often calculated using input-output multipliers. However, this is not appropriate in most cases for the following reasons: given limited Government funds, the funding for the proposal could be spent on a range of other uses, all of which will also have flow on effects. Counting multipliers for the expenditure, without taking into account the multiplier effect of the alternative use of the funds, would bias the results for the proposal upwards; and input-output multipliers suffer from various shortcomings and are not a valid method of calculating economy-wide impacts. For example, multipliers assume that a new project could access unlimited amounts of goods and labour at the pre-project market price, which is often not the case. One example when it is valid to measure the economy-wide impact is if the proposal is aimed at attracting private investment to the State (for example, for multi-user infrastructure in an industrial area). The net impact of such a proposal would be very complex due to (say) the occurrence of foreign investment inflows, exports and foreign dividend outflows. In this case, computable general equilibrium modelling is the appropriate method to analyse the benefits. This modelling can be time intensive and expensive, and will only add value for complex proposals. For lower risk proposals, the use of first-round benefit analysis is sufficient and input-output multipliers are not used. 23 Glossary Term Definition Accrual Accounting Recognition and recording of revenue, expenses, assets and liabilities at the time they arise or are incurred. Benefit A gain in consumer satisfaction or welfare resulting from an option. Benefit Cost Ratio Ratio of the present value of benefits to the present value of costs. Cash Flow The basic tool of discounted cash flow analysis. Any receipt or payment of money realised or foregone because of the existence of a project. Consolidated Account The Account maintained under Section 64 of the Constitution Act into which all revenues are paid, and from which all State expenditure is met, unless prescribed revenues are directed to specific purposes by Acts of Parliament. Outlays of a capital nature are usually identified, but no distinction is made in the financing of recurrent or capital outlays. Contract An agreement entered into by two or more parties, whereby legal obligations are created. Cost Benefit Analysis A technique for the evaluation of options where costs and benefits (both direct and indirect) are considered. Most costs and benefits are valued, but when this is not possible, they are at least listed. Decision Criteria Factors referenced, prioritised and weighed by decisionmakers. These may include key statistics which form the basis for deciding the worthiness of an option. Discount Rate Typically, options analysis requires the consideration of costs and benefits that occur at different points in time. The discount rate is used to calculate the present value of future cash flows. It reflects the opportunity cost of using funds for a particular option, rather than having them available for an alternative use. Economic Analysis The systematic means of analysing the costs and benefits of the various methods by which the objectives of an option can be met. Considers costs and benefits accruing to the sponsor agency, as well as to other Government agencies, private enterprise, individuals and the community. Financial Analysis An evaluation technique which is undertaken from the perspective of the individual agency, rather than having an economy-wide perspective, as used in cost benefit analysis. Hurdle Rate A discount rate that is used as a benchmark to determine whether a proposal would be viable, particularly under the IRR method. Hurdle rates are most appropriately used in agency financial analysis, rather than economic analysis. Interest Expenses Also known as debt servicing costs. Interest and other 24 Term Definition expenses associated with the financing of an option are excluded from the economic evaluation. They are taken into account in the discount rate. Internal Rate of Return The discount rate that equates the present value of benefits with the present value of costs of an option. Net Present Value The sum of the discounted benefits less discounted costs of an option. Nominal Vs Real Real cash flows make no allowance for expected inflation. Thus, a real cash flow of $100 occurring after two years, with expected inflation of 7% for each year, will be equal to a nominal cash flow of $114.49 (100 x (1.072)). Non-Asset Initiatives Methods of addressing increases in demand other than by adding asset capacity (i.e. pricing mechanisms, selective targeting of services, etc). Opportunity Cost The benefit foregone of the next best use of resources. Opportunity cost is the critical cost concept in economic evaluation. Option A means that requires the weighing up of costs and benefits in order to meet an outcome. As such, the term is not restricted to a capital works or recurrent activity. Payback Rule A method of assessment in which the decision criteria are focused on how long it takes for expected revenues or savings to pay back the initial capital cost. Perpetuity A stream of cash flows that are of equal size, and spaced uniformly in time, that do not cease. Present Value The equivalent value today of a benefit or cost to be incurred at some future point in time. Real Rate of Return Revenue less costs (excluding interest), divided by the current value of assets used, expressed as an annual rate. Residual Value Resale value of an asset at the expiry of its useful life or an assigned value at the end of the analysis period, which reflects net benefits beyond that period. Resources Commonly referred to as inputs in a production process (such as land, labour, capital). Risk (investment) The extent of variability in the expected return from an option. Sensitivity Analysis A technique used to assess key variables. It shows how changes in the values of various factors affect the overall value of an option. Service The delivery of an output or function to an external user. Social Impact Analysis The analysis of unquantifiable gains and losses from an option, including an assessment of distributional impacts and the impact on individuals (by age, community group, etc). 25 Term Definition Sunk Costs and Benefits A cost or benefit that has already occurred and is irreversible. Sunk costs and benefits are irrelevant in the economic evaluation of options, because the evaluation considers future costs and benefits. 26