Ronfeldt, Matthew, Hamilton Lankford, Susanna Loeb, and James

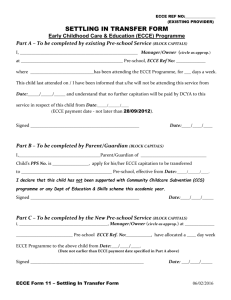

advertisement

The early childhood care and education workforce in the United States: Understanding changes from 1990 through 2010 Daphna Bassok, University of Virginia, dbassok@virginia.edu Maria Fitzpatrick, Cornell University, mdf98@cornell.edu Susanna Loeb, Stanford University, sloeb@stanford.edu Agustina S. Paglayan, Stanford University, paglayan@stanford.edu DRAFT – DO NOT CITE WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE AUTHORS We are grateful to Bruce Fuller and Deborah Stipek for useful comments on previous drafts of this paper. This research was supported by a grant from the Institute of Education Sciences (R305A100574). The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Virginia, Cornell University, Stanford University, or IES. Any remaining errors are our own responsibility. 1 ABSTRACT Despite heightened policy interest in improving the quality of the early childhood care and education (ECCE) workforce, very little is known about the characteristics of this workforce or the extent to which these characteristics have changed over time. Using nationally-representative data, this paper fills this gap by documenting changes between 1990-2010 in the educational attainment, compensation and turnover of the ECCE workforce overall and within each of the three sectors that compose it: centers, homes and schools. We find that the average educational attainment and compensation of ECCE workers, as well as the prestige of those entering the workforce, increased substantially over the period studied, and that turnover decreased. We also document a major shift in the composition of the ECCE workforce towards center-based settings and away from home-based settings. Although this shift towards more regulated settings provides one plausible explanation for the overall improvements, we actually find that the improvements in the characteristics of the ECCE workforce were primarily driven by changes within each of the sectors rather than by the shift away from home-based settings towards centers. Further, we show that the home-based workforce exhibited the most profound changes over the period examined. 2 INTRODUCTION In the United States, most children ages five and under regularly receive care by someone other than their parents, including relatives, babysitters and workers employed by day care centers or preschool programs (U.S. Census Bureau 2010, Bassok 2010). High-quality early childhood experiences are linked to substantial short- and long-term benefits both for the individual and for society (Knudsen, Heckman, Cameron and Shonkoff 2006; National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2007). As in the K-12 sphere, where it is routinely acknowledged that teachers are the most important school-level determinant of children’s learning, a growing body of evidence suggests that the quality of early childhood experiences also depends largely on the quality of the caregiver or teacher (e.g., see Shonkoff and Phillips 2000, Peisner-Feinberg et al. 2001, National Scientific Council on the Developing Child 2004, and Hamre and Pianta 2006). The increased recognition of the importance of early childhood care and education (ECCE) in general, and of ECCE providers in particular, has led to heightened policy interest, at both the federal and state levels, in strengthening the quality of the ECCE workforce. For instance, in 2011 the federal government funded the Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge, a competitive grant program to support states in their efforts to improve early childhood education programs, and identified “supporting a great early childhood education workforce” as one of five key areas of reform. Similarly, the latest reauthorization of the federal Head Start program requires that fifty percent of Head Start teachers hold a Bachelor’s degree (BA) in child development or a related field by 2013 (Barnett et al. 2010). Further, twenty-five states are operating or developing Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS) to assess and improve the quality of ECCE providers, and many of these QRIS 3 programs offer financial incentives to providers that invest in their employees’ education and training (Tout et al. 2010) . To inform policy, and to guide further research, it is important to establish whether the increased efforts to improve the quality of the ECCE workforce have been accompanied by any changes in the characteristics of this workforce. Historically described as a low-education, low-compensation, high-turnover workforce (Howes, Phillips and Whitebook 1992; Cost, Quality and Outcomes Study Team 1995; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network 2000; Vandell and Wolfe 2000), more recent studies suggest that the qualifications, compensation and stability of ECCE workers continue to be worryingly low. For instance, Herzenberg, Price and Bradley (2005) report that in the years 2002 through 2004, teachers and administrators working in early childhood education made about 10 dollars per hour, roughly half as much as the average female college graduate. Another study surveying child care centers in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska and Missouri in 2001, found that 40 percent of caregivers intended to leave the ECCE industry within less than five years (Torquati, Raikes and Huddleston-Casas 2007), a figure consistent with estimations of actual turnover from California child care centers between 1996 and 2000 (Whitebook et al. 2001). Indeed, efforts to measure changes in the ECCE workforce over time suggest that the qualifications of center-based workers have either changed little or declined (Whitebook et al. 2001; Saluja, Early and Clifford 2002; Herzenberg, Price and Bradley 2005; Bellm and Whitebook 2006). However, earlier attempts to describe the evolution of the ECCE workforce provide an incomplete picture – and even constructing an accurate description of the ECCE workforce at a single point in time has proved complex. First, many of the relevant studies concentrate on a single state or even a single local community, making generalizability problematic. Second, 4 most studies use only cross-sectional data which do not allow researchers to track changes in the characteristics of the workforce over time. Finally, the bulk of studies focus only on a single segment of the ECCE industry (i.e. only state preschool programs or only child care centers). In contrast to elementary and secondary education, where public schools are the main supplier and adhere to uniform state-level regulations, the provision of ECCE services is quite fragmented, spread between public, for-profit and non-profit private providers. Several studies have emphasized the difficulty of understanding the evolution of the ECCE workforce over time, given the lack of longitudinal data needed to track individual workers, or even the lack of comparable cross-sectional data about the workforce for multiple points in time (Saluja, Early and Clifford 2002; Brandon and Martinez-Beck 2006; Kagan, Kauerz and Tarrant, 2008). Information about ECCE workers in home-based settings is particularly limited. The current study is unique in that it addresses all three of the limitations of previous studies discussed above. We make use of national, longitudinal data that encompass workers in all three ECCE sectors: centers, homes and schools. We address two main research questions. First, we ask how the characteristics of the ECCE workforce in the U.S. changed over the period 1990-2010. As discussed below, our interest is in the evolution of characteristics that plausibly proxy for quality. Second, we describe changes separately within each of the three ECCE sectors and ask to what extent are the overall changes in the characteristics of the ECCE workforce explained by a redistribution of the workforce across center-, home- and school-based childcare, and to what extent they are explained by changes in the characteristics of the workforces within each of these sectors. 5 Over the past twenty years there has been a substantial increase in the utilization of “formal” ECCE settings and in turn a decline in the share of workers employed in home-based settings (Bassok, Fitzpatrick and Loeb, in preparation). This decline in the relative importance of the home-based sector –often singled out as the lowest-quality sector– may drive overall changes in the ECCE labor force over time. On the other hand, changes in the characteristics of the aggregate ECCE workforce could also be driven by changes in the characteristics of the workers employed within each sector. By decomposing the overall change trends, we shed light on the mechanism by which the industry has changed over time, and explore the extent to which improvements over time in the ECCE workforce have been driven by the policy focus on expanding and improving the formal sector. We find that the educational attainment and compensation of the national ECCE workforce increased over the period of analysis, and that turnover from the ECCE industry decreased substantially. Our results differ substantially from earlier studies that highlight negative or stagnant trends in the ECCE workforce (Whitebook et al. 2001; Saluja, Early and Clifford 2002; Herzenberg, Price and Bradley 2005; Bellm and Whitebook 2006; Whitebook and Ryan 2011). These differences are likely explained by our focus on a more recent period of analysis (1990-2010) and by our use of national data including workers from all three child care sectors. Our results show that changes in the characteristics of the national workforce are mostly explained by changes in the characteristics of workers within each sector and less so by a redistribution of workers from home-based to center- and school-based settings. Surprisingly, we find that while the characteristics center-based workers exhibited increases in compensation and decreases in industry turnover, changes along all dimensions analyzed were most pronounced among home-based workers. 6 ECCE Worker Characteristics Throughout the paper we focus on the evolution of four workforce characteristics: (1) the educational attainment of workers; (2) their compensation; (3) the probability of leaving the ECCE industry; and (4) the socioeconomic and occupational prestige of those who move from another industry into the ECCE workforce. In this section we explain the rationale for exploring each of these measures. Although none of these characteristics are direct measures of caregiver quality, we argue that given the dearth of direct measures of quality, particularly longitudinally or at the national level, each of our four measures serves as a strong potential proxy for caregiver effectiveness. Indeed, in recent years many states have implemented policies aimed at improving ECCE quality by mandating higher levels of education for workers, increasing wages and promoting a reduction in turnover. Improvements along these dimensions are likely to reflect an increased ability to attract and retain qualified workers into the ECCE industry, and are hypothesized to lead to higher quality experiences for young children. There is ongoing debate about the causal link between formal education and ECCE worker quality. In their review of this literature, Tout, Zaslow and Barry (2006) report that most studies find a positive association between worker education levels and the overall quality of care. Blau (2000), for example, shows that ECCE workers who have a high school degree or some college education implement better classroom practices than otherwise comparable workers who have not completed high school. On the other hand, evidence about the importance of specific degrees (e.g. BA) for better classroom practices and child outcomes is more mixed, with several studies reporting no significant relationships (Blau 1999, 2000; NICHD 2000; Currie and Neidell 2003; Barnett 2003; Kelley and Camilli 2007; Early et al. 7 2007). However, many of these studies fail to control for factors that are likely to be correlated with both workers’ education and the quality of care, and therefore we cannot make conclusive statements about whether and how specific education degrees affect the quality of care. Even in the absence of conclusive evidence of a causal link between specific education degrees and quality, there are pragmatic and policy reasons to examine whether there have been changes in the education levels of ECCE workers, as this is often used to measure the quality of ECCE services: most states require public pre-kindergarten teachers to hold a BA; the federal government requires that fifty percent of Head Start teachers hold a BA in child development or a related field by 2013 (Barnett et al. 2010); and many of the Quality Rating and Improvement Systems used by states to evaluate the quality of ECCE providers award a higher rating to those providers whose teachers and directors hold a BA (Administration for Children and Families 2010). Moreover, an increase in the educational attainment of workers (including an increase in the proportion of workers with BAs) may reflect an improved ability of employers to be selective when recruiting individuals into the ECCE workforce. A more educated workforce may also reflect that the ECCE industry has become a more attractive job alternative. Workers’ wages provide a second potential proxy for quality. Research suggests a positive association between workers’ wages and the quality of classroom practices, perhaps because higher compensation helps to attract and retain qualified workers as well as motivate those already in the ECCE profession (Mocan et al.1995; Blau 2000). In addition, there is some evidence that higher wages are associated with a lower probability of turnover from the child care profession, especially among more educated workers (Whitebook and Sakai 2003). 8 In contrast to education and wages, which are considered “structural” features of quality because they can be directly regulated or altered, industry turnover, our third measure, may provide a more direct proxy for the quality of child-caregiver interactions. At the elementary school level teacher turnover is related to lower reading and math gains (Ronfeldt, Lankford, Loeb, Wyckoff, 2011). While the research on the impacts of turnover in early childhood settings is limited, Tran & Winsler (2011) found that low-income children in center-based care who experience a change in primary caregiver over the course of a year scored lower on most measures of school readiness compared to children with a stable caregiver. Further, the number of months that a child spends with a caregiver is positively related to the quality of the child-caregiver relationship (Elicker, Fortner-Wood and Noppe 1999). Aside from its direct effect on children’s experiences, high turnover may lead both employers and employees to invest little in building skills that are specific to the childcare profession. Our final outcome is the socioeconomic and occupational prestige of those who move from another industry to the ECCE workforce. Prestige is a measure of the desirability of an occupation such that changes in this measure over time may signal a change in the industry’s capacity to attract and retain qualified workers. EMPIRICAL APPROACH Data We use data from the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS is a monthly household survey administered by the U.S. Census and the Bureau of Labor Statistics that focuses on the labor force status and demographic characteristics of the working-age population. The CPS sample consists of approximately 50,000 households and is nationally 9 representative. Households from all fifty states and the District of Columbia are in the survey for four consecutive months, out for eight, and then return for another four months before leaving the sample permanently. The fieldwork is conducted during the calendar week that includes the 19th of the month. The period of reference for most questions is the week before the survey, but the March Supplement also includes some questions that refer to the previous calendar year (U.S. Census Bureau 2006). For all employed individuals surveyed, the CPS collects information about the industry and occupation in which they work, using the same categories as the Census 1990 and 2002 Industry and Occupational Codes.1 We use these codes to identify ECCE workers and to distinguish between center-, home-, and school-based workers. The center-based ECCE workforce includes all workers who are not self-employed, and who either work in the “child day care services” industry, or have child care occupations (e.g., “child care workers”, “prekindergarten or kindergarten teachers”, “early childhood teacher’s assistants”) and work in an industry other than “elementary and secondary schools”, “private households”, “individual and family services”, or “family child care homes”.2 The home-based ECCE workforce includes all self-employed individuals who work in the “child day care services” industry; all those employed in the “family child care homes” industry; those who have child care occupations (e.g., “child care workers”, “private household child care workers”, “pre-kindergarten or kindergarten teachers”, “early childhood teacher’s assistants”) and are employed in the “private households” or “individual and family services” industries; and those who have child The 1990 Census Codes are used to categorize the industry and occupation of workers before January 2003. Beginning in January of 2003, the 2002 Census Codes are used (U.S. Census Bureau 2006). 2 On average over the period 1990-2010, 82.8 percent of individuals identified as center-based ECCE workers were employed in the “child day care services” industry, and the remaining 17.2 percent were employed in other industries. 1 10 care occupations and are self-employed in other industries except for “elementary and secondary schools”.3 Our ability to track home-based ECCE workers over time represents an advantage over previous studies, including those that have also relied on the CPS to identify child care workers (Herzenberg, Price and Bradley 2005).4 Finally, the school-based ECCE workforce includes “pre-kindergarten and kindergarten teachers” and “early childhood teacher assistants” employed in the “elementary and secondary schools” industry.5 For each individual in the survey, we are able to identify both whether they were an ECCE worker in the week of reference and if their longest job in the previous calendar year was an ECCE job. The workforce characteristics that we analyze are measured as follows: Educational attainment: Since 1992, the CPS has collected information about each household member’s highest level of education completed as of the week of reference. In keeping with prior studies, we describe changes in the share of ECCE workers with less than a high school degree, exactly a high school degree, at least some college education but no BA, and at least a BA. Information on educational attainment is available from 1992 to 2010. Compensation: The CPS collects information about an individual’s annual earnings from the longest job held in the previous calendar year. We describe changes in the mean annual earnings of those whose main job in the previous calendar year was an ECCE job. We also estimate the hourly earnings of these workers, restricting our estimation to those who were It should be noted that, since home-based workers are identified based on individuals’ responses concerning their employment status, type of employer, industry and occupation, it is likely that some individuals who take care of a relative’s child (e.g., grandparents, aunts) identify themselves as child care workers, especially if they receive some form of compensation for doing so. 4 As Herzenberg et al. (2005) point out, some of the codes relevant to identifying home-based workers before 2003 were no longer available from 2003 on. However, while they conclude that this makes it difficult to track home-based workers over time, we do not observe any sharp discontinuities in either the number of homebased workers or in the share of home-based workers in the national ECCE workforce before and after 2003. These findings are available from the authors upon request. 5 Note that some workers might be employed in the “child day care services” industry but perform duties that are not directly related to the care of children. This might include, for example, cooks, bus drivers, janitors, gardeners, or secretaries. We do not include those workers in our analysis of the ECCE workforce. 3 11 full-year workers in the previous calendar year.6 We express both earnings variables in 2010 dollars. In addition, we describe the evolution of a variable that gives us a sense of non-salary forms of compensation: the share of ECCE workers whose employer helped pay for a pension and/or health plan. Individuals report whether any employer helped pay for pension/health plans in the previous calendar year. Therefore, as with the earnings variables, these variables are measured among those whose main job in the previous calendar year was an ECCE job. Moreover, to capture whether an individual received benefits from an ECCE employer, we restrict our analysis of non-salary benefits to those who report that they had only one employer in the previous calendar year.7 Information on earnings and benefits is available from 1990 to 2009. Year-to-year industry turnover: To measure child care industry turnover rates, we exploit the fact that the CPS provides information about an individual’s industry and occupation both in the week of reference and for the longest job held in the previous calendar year. Among individuals whose main job in the previous calendar year was an ECCE job, we estimate the industry turnover rate as the share of those who were no longer in the ECCE workforce during the week of reference. An analogous method is used by Harris and Adams (2007) to measure turnover from elementary and secondary teaching. Information on industry turnover is available from 1990 to 2010. Note that our measure only captures whether The CPS collects information about hourly wages for a subsample of the March interviewees that excludes all self-employed individuals, thus excluding a large proportion of home-based workers. We estimated the hourly wages of ECCE workers using the information collected by the CPS about annual earnings from the main job held in the previous calendar year; number of hours worked in a typical working week in the previous calendar year; and full/part-year employment status in that year. We estimate the hourly earnings from their main job among full-year workers whose main job was an ECCE job, assuming that these individuals worked fifty weeks during the previous calendar year, and that the fifty weeks were devoted to their ECCE job. Among all workers whose main job in the previous calendar year was an ECCE job, the proportion who worked on a full-year basis –and to whom our estimates apply– increased from 46 percent in 1990 to 65 percent in 2010. 7 Among all workers whose main job in the previous calendar year was an ECCE job, the proportion who had only one employer increased from 75 percent in 1990 to 84 percent in 2010. 6 12 individuals remained in the ECCE workforce or not, but among those that did, it does not distinguish between individuals who changed jobs. Thus, year-to-year industry turnover is a lower bound estimate of the level of instability experienced by children. Occupational prestige of entrants into the ECCE workforce: We combine the information on a worker’s occupation provided by the CPS, with the methodology developed by Charles Nam and colleagues (Nam 2000; Nam and Boyd 2004), to create a new variable that assigns each individual an occupational status score. These scores are based on the median earnings and median educational attainment of workers within a particular occupational category. They take values from 0 to 100, and can be interpreted as the percentage of individuals in the civilian labor force who are in occupations with combined levels of education and earnings below that occupation.8 We use these scores to examine the average occupational status in the calendar year before the survey of individuals whose main job in that year was outside the ECCE industry, but who were ECCE workers in the week of reference. Information on this variable is available from 1990 to 2010. Methods As described above our two research questions are: (1) How have the characteristics of the ECCE workforce changed over the past two decades? (2) To what extent are changes in the characteristics of the ECCE workforce explained by a redistribution of the workforce across center-, home- and school-based child care, and to what extent are they explained by changes in the characteristics of the workforces within each of these sectors? We assign the Nam-Powers-Terrie occupational status scores to observations before 2003. These scores were created based on the earnings and education distributions of the civilian labor force corresponding to the 1990 Census (Nam 2000). From 2003 on, observations are assigned the Nam-Powers-Boyd scores, which were created based on the distributions corresponding to the 2000 Census (Nam and Boyd 2004). 8 13 To address our first research question, we analyze changes in our variables of interest over the period 1990-2010, except for the case of educational attainment, which can only be analyzed from 1992 onwards. We assess whether the changes we observe are unique to the ECCE workforce by comparing them to changes among two other groups: all female workers and a selected group of low-wage workers. Female workers are a relevant comparison group as females comprise the vast majority of ECCE workers. 9 We also compare ECCE workers to other low-wage workers, specifically those in any of the following industries: beauty salons, food services, entertainment and recreation services, grocery stores, department stores, and non-teaching jobs in elementary and secondary schools (e.g., bus drivers, cooks, janitors, teacher aides, secretaries and administrative assistants). We choose this specific set of industries because they are the main low-wage industries from which ECCE workers come when they enter the child care industry, as well as the main industries to which they migrate when they leave the ECCE workforce.10 Throughout all our analysis we use three-year moving averages in order to increase the precision of our estimates.11 To address our second research question, we perform two sets of simulations.12 First, we estimate what the overall change in the ECCE workforce’s characteristics would have been had the distribution of the workforce across the three sectors changed as it did over the period of analysis, but assuming that the characteristics of workers within each sector remained the same as in 1990 (or 1992 in the case of education). Second, we estimate what Based on our calculations, over 95 percent of ECCE workers over the period of analysis were women. Together, over the full period of the study, they represent about a third of migration from another industry into child care, and from child care to another industry. 11 For example, the share of ECCE workers with less than a high school degree in year 2007 is, in fact, the share of workers with less than a high school degree in the pooled cross-section of observations from 2006, 2007 and 2008; the share of workers with less than a high school degree in year 2008 relies on pooled data from 2007, 2008 and 2009, and so on. 12 The equations used for these simulations are provided in the Technical Appendix. 9 10 14 the overall change in the workforce’s characteristics would have been had the characteristics of the workers within each of the sectors changed as they did, but assuming that the distribution of the workforce across the sectors remained the same as in 1990 (or again, 1992 in the case of education). RESULTS Changes in the characteristics of the ECCE workforce in 1990-2010 We begin by examining changes in the ECCE workforce as a whole, and find that all of the characteristics analyzed –education, compensation, turnover and prestige of entrants– changed in the direction hypothesized to improve ECCE quality. Table 1 and Figure 1 show that the share of ECCE workers with at least some college education rose from 47 to 62 percent between 1992 and 2010. The mean annual earnings among ECCE workers also increased by 51 percent, from $10,746 to $16,215.13 While part of this increase was driven by an increase in the number of hours worked by ECCE workers14, the mean hourly earnings of ECCE workers also increased substantially over that period (by 33 percent, from $8.8 to $11.7 per hour).15 Similarly, the share of ECCE workers whose employers provided pension and health benefits also increased (from 19 percent in 1990 to 28 percent in 2009). Annual turnover from the ECCE industry decreased dramatically over the period of analysis (from 32.9 percent in 1990 to 23.6 percent in 2010). Finally, individuals who in 2010 moved into child care from other occupations came from more prestigious occupations than Recall that all earnings figures are expressed at 2010 dollars. The earnings reported correspond to those received in the calendar year before the survey. Since we employ CPS survey data up to March of 2010, the last period of reference for the earnings variables corresponds to calendar year 2009. 14 The mean number of hours worked per week among ECCE workers increased from 29.9 to 31.8 between 1990 and 2010. 15 Hourly earnings are our own estimation and apply to individuals whose main job in the calendar year before the survey was an ECCE job, and who were full-year workers during that year. For details on how this variable was estimated, see the Empirical Approach section. 13 15 those who moved into child care in 1990: the average occupational prestige score of ECCE entrants increase by 4.7 percentiles over this period, from 37.6 to 42.3.16 Taken together, these results suggest substantial change in the characteristics of ECCE workers, and in all cases these changes are in the direction posited to improve quality. To put the ECCE patterns into context, we next compare the characteristics of this workforce to those of both female workers generally and a sample of low-wage workers. In 1990, ECCE workers had substantially lower annual earnings and hourly earnings than either of these groups. They were also far less likely to receive pension or health benefits and much more likely to leave their industry. In most cases, the changes observed among ECCE between 1990 and 2010 were more marked than those observed among the comparison groups. For instance, the ECCE workforce showed a larger increase in mean annual earnings than the female workforce (by 51 vs. 25 percent, respectively) and in hourly earnings (by 33 vs. 17 percent); a larger increase in the share of workers with employer-provided pension or health benefits (by 9 vs. 1.5 p.p.); and a steeper decline in industry turnover (by 9.3 vs. 6.8 p.p.). While the share of workers with at least a BA increased somewhat less than for female workers overall, the percentage with at least a high school degree increased more. All selected variables exhibited a larger improvement among ECCE workers compared to low-wage workers. Not only did the improvements observed among ECCE workers go above and This change is marginally statistically significant. Throughout the paper, we use the term “significant” to refer to changes that were statistically significantly different from zero at the 5 percent level. In the case of changes in the average occupational prestige score of those entering the ECCE workforce, the change was statistically significantly different from zero at the 15 percent level. Note that in the case of educational attainment, annual earnings and industry turnover, the analysis applies to the full sample of ECCE workers; and in the case of hourly earnings and pension/health benefits, it applies to a substantial fraction of this sample. In contrast, the analysis of average occupational prestige scores applies only to individuals who entered the ECCE workforce in a given year. This is a small sample, and estimates are therefore noisy, which is why for this variable we evaluate significance not only at 5 but also at the 10 and 15 percent level. 16 16 beyond general trends, but the changes observed reflect a stable trend within the ECCE industry and are not the product of the economic crisis that began in 2008.17 Decomposition of the changes in the quality of the ECCE workforce: Changes in the relative importance of the sectors, or changes within the sectors? In 2010, about 56 percent of ECCE workers were employed in center-based settings; 26 percent, in home-based settings; and 18 percent, in schools. As shown in Figure 1, between 1990 and 2010, there was a significant redistribution of ECCE workers: the relative importance of home-based workers declined (by 21.8 percentage points), and this was compensated mostly by an increase in the relative importance of center-based workers (by 17.5 p.p.), and by a small increase in the relative importance of school-based workers (by 4.3 p.p.). It is worthwhile to note that although the relative importance of school-based workers increased only slightly, the number of workers in this sector increased by 45 percent between 1990 and 2010, a trend consistent with both the expansion in the provision of state prekindergarten programs and the shift from part- to full-day kindergartens. The number of center-based workers also increased dramatically over the period of analysis (by 61 percent), while the number of home-based workers decreased (by 39 percent). The redistribution of ECCE workers from child care homes to centers and schools is consistent with the recent One plausible hypothesis for the reason underlying the observed improvements in ECCE workers’ qualifications and stability is that these changes may be the product of the economic crisis and do not reflect stable trends. For instance, the crisis may have enabled ECCE employers to be more selective in terms of who they hired or retained; may have led unemployed workers to take jobs for which they were over-qualified; and may have encouraged workers to stay in the ECCE industry for more time than they had planned. However, in a supplementary analysis not shown, we explored whether the observed trends reflect a relatively stable pattern over the entire period or whether there were changes in trends following the economic crisis that began in 2008. To do this we look separately at changes over 1990-2007 and 2007-2010. If anything, our results suggest that the improvement of ECCE workers’ characteristics was stalled or reversed, not accentuated, during the crisis period. However, differences between 2007 and 2010 are not statistically significant. Results are available from the authors upon request. 17 17 decline in the share of children under age five whose main child care arrangement is in a home setting (U.S. Census Bureau 2005). As shown inFigure 2, and in line with prior research, in all time periods home-based workers had far lower levels of education and compensation and higher levels of turnover from the ECCE industry than center- or school-based workers. Thus, the decline in the relative importance of home-based workers may have contributed to the observed increase in the educational attainment, compensation and stability of the national ECCE workforce discussed earlier. However, the changes observed in the aggregate workforce may also be explained by changes within the sectors, including changes within the home-based workforce. Indeed, the period 1990-2010 saw a change in the characteristics of ECCE workers within each of the sectors. As described in Table 2, home-based workers, and to a lesser extent center-based workers, experienced changes that suggest an overall improvement in quality, while school-based workers did not change significantly. Among center-based ECCE workers, there was a significant increase in average annual earnings (by 35 percent between 1990 and 2009) and in average hourly earnings (by 18 percent). Moreover, there was a significant decrease in the share of center-based workers who left the ECCE industry from one year to the next (by 9.6 p.p., from 34 percent in 1990 to 24.4 percent in 2010). Indeed, the decrease in industry turnover among center-based workers was more pronounced than that observed among female or low-wage workers. The remainder of outcomes considered also showed changes in a direction consistent with improvement, but the changes were not statistically significantly different from zero. Among home-based ECCE workers, all the characteristics of interest improved significantly and substantially over the period of analysis. With respect to educational 18 attainment, there was a significant increase in the share of workers with at least some college (by 21.4 p.p.), and a significant decrease in the share of workers with less than a high school degree (by 17.8 p.p.). The average annual and hourly earnings of home-based workers increased by 92 and 50 percent, respectively, between 1990 and 2009, and there was a significant increase in the share of home-based workers with pension or health benefits (by 4.5 p.p.). Finally, turnover from the child care industry declined substantially among homebased workers (by 8.4 p.p., from 36.9 percent in 1990 to 28.5 in 2010). Notably, the magnitude of the improvements within the home-based workforce exceeded that of the female and low-wage workforces for all characteristics. In summary, over the period of analysis there was a substantial decline in the share of home-based ECCE workers, driven largely by an increase in the share of center-based workers as well as a slight increase in the share of school-based workers. While considerable differences remain between sectors with respect to all the characteristics analyzed, the pronounced changes within the home-based sector imply a narrowing of the gap with respect to the other two sectors. The results suggest that overall improvements observed for the ECCE workforce as a whole may be driven both by the decline in the prevalence of homebased workers and by changes in the characteristics of workers within each of the sectors. In a final analysis we decompose the change in the characteristics of the aggregate ECCE workforce into the component explained by the expansion of the formal sector and the component explained by changes in the characteristics of workers within the sectors. Our estimations are presented in Table 3. While both factors contribute to the overall change, for most variables (educational attainment, annual and hourly wages, and industry turnover), most of the aggregate improvement is explained by changes within the sectors, with changes 19 in the relative importance of the sectors explaining only a small portion of the overall improvement. For example, 78 percent of the increase in average annual earnings between 1990 and 2009 is explained by increases in the earnings of workers within the sectors, and only the remaining 22 percent is explained by the redistribution of workers. Similarly, 86 percent of the substantial fall in the child care industry turnover rate is explained by a fall in the turnover rate of each sector’s workforce, while only 14 percent was explained by the redistribution of workers across sectors. Given the importance of within-sector changes in explaining the overall changes in the characteristics of the aggregate ECCE workforce, we estimated each sector’s contribution to the part of the overall change attributable to within-sector changes. Our findings are reported in Table 4. Most of the changes in educational attainment and earnings that is attributable to within-sector changes are explained by changes within the home-based ECCE workforce. Indeed, over two thirds of the increases in the ECCE workforce’s educational attainment and over fifty percent of the changes in compensation that are attributable to within-sector changes are driven by improvements within the home-based sector. DISCUSSION Our study contributes to the existing literature about the ECCE workforce in several key ways. Using data from the CPS, we are able to describe changes in the national ECCE workforce as a whole, in each of the three sectors that compose it, and for a more recent period than previous studies. A key goal of the paper was to understand whether and how the ECCE workforce has changed over time, particularly with respect to a set of characteristics that may proxy for the quality of the ECCE experiences available to children: workers’ educational attainment, compensation, turnover from the child care industry, and the occupational prestige of those 20 entering the workforce. Our findings suggest that over the period 1990-2010, the ECCE workforce as a whole exhibited signs of improvement along all of these characteristics. Moreover, for all of the characteristics considered, the improvements observed within the ECCE workforce were more pronounced than those observed among other low-wage workers, and for most characteristics they were also more pronounced than those observed among female workers. In contrast, prior studies reported a decline or little change in the educational attainment and compensation of the ECCE workforce. However, these earlier studies have generally focused on the center-based workforce, and have not addressed the evolution of the school- and home-based workforces (Whitebook et al. 2001; Saluja, Early and Clifford 2002; Herzenberg, Price and Bradley 2005; Bellm and Whitebook 2006). The most recent of these studies relies on the same data used in the current study to describe the evolution of the center-based workforce up to 2003 (Herzenberg, Price and Bradley 2005). It reports a decline in the share of the center-based workforce with a BA. This is consistent with our findings. However, beginning in 2004 and up to 2010, we observe a reversal of this trend. Overall we do not observe significant changes in the educational attainment of the center-based workforce over the period 1990-2010, but we do see significant improvements in the compensation and stability of this workforce. In addition to providing new information about the changing characteristics of the ECCE workforce, we also document a dramatic reconfiguration of the ECCE workforce, such that the majority of workers now work in formal rather than home-based settings. Given that center- and school-based workers tend to have substantially higher education levels, salaries, and stability, it would seem plausible that the shift towards more formalized types of care 21 explains the overall positive trends in the industry. Surprisingly, however, we show that the shift away from home-based care and towards center settings is not the primary explanation for the changes observed in the industry at large. In fact, most of the improvement in the ECCE workforce is attributable to improvements in the characteristics of workers within the sectors, with the redistribution of workers from informal to formal settings explaining only a small portion of the overall changes. Further, while the center-based workforce exhibited significant increases in earnings and a remarkable decline in industry turnover, changes within the home-based workforce were the primary driver of the changes in educational attainment and earnings observed for the ECCE workforce as a whole. These findings –that the overall improvement of the ECCE workforce was primarily driven by improvements within the home-based workforce– are puzzling in light of the heightened policy interest in the expansion and improvement of more formalized ECCE settings such as preschools and pre-kindergarten programs. Improvements observed within the home-based workforce may be related to recent efforts to increase the qualifications and stability of these workers. These efforts include programs introduced to support and reward participation in professional development and the acquisition of further education; supplement the wages of ECCE workers to ensure they meet a locally-determined minimum living wage; facilitate the provision of employer-sponsored health plans by pooling together workers from different child care centers and homes; provide technical assistance to homebased providers; and hold child care providers accountable for the quality of services they provide (Kagan, Kauerz and Tarrant 2008). Further research is needed to understand the extent to which these efforts have contributed to the observed improvement in the education, compensation and stability of home-based workers. 22 The current study provides new evidence about the changing nature of ECCE and particularly about the changing characteristics of home-based ECCE workers. While the CPS allows us to describe this labor force in greater detail than previous studies, the CPS was not designed to study the ECCE industry, and several of its limitations with respect to the current study are worth highlighting. First, while the CPS provides information about structural features of ECCE quality such as the education and compensation of workers, it cannot be used to assess whether and how the processes within ECCE settings have changed. Turnover from the ECCE industry may proxy for the quality of ECCE processes, as the stability of workers is likely to impact the quality of the relationships they build with the children under their care as well as how much they invest in building skills that are specific to child care jobs. However, turnover is still a proxy. A more direct measure of quality would involve observing and assessing the quality of child-caregiver interactions or linking ECCE workers with data on the learning gains of the children they serve. Indeed, much remains to be known in terms of whether and how processes within ECCE settings have changed. A second limitation of this study is the sample size. Each March Supplement of the CPS between 1990 and 2010 contains, on average, 673, 532 and 227 center-, home-, and schoolbased ECCE workers, respectively. By pooling together observations from three consecutive years and calculating three-year moving averages, we were able to describe the evolution of the center- and home-based workforces with reasonable precision. However, in the case of the school-based workforce, the direction of the changes was consistent with an improvement, but the changes were not statistically significant. We don’t know whether this is because, in fact, there was little change within this workforce, or because the sample was too small and the estimations too volatile. Further research relying on other data sources 23 could compare the trajectory of the school-based sector in states that have made considerable investments in expanding its provision, vis-à-vis states that have not. The third limitation lies in that our study cannot distinguish between ECCE workers who work with infants and toddlers, and those who work with preschoolers. These limitations notwithstanding, our findings shed an optimistic light on the possibility of improving ECCE opportunities. First, they show that the qualifications, compensation and stability of the ECCE workforce can improve, and in fact have improved over the past two decades. The decline in turnover from the ECCE industry has been particularly marked, and is observed both among home- and center-based workers. While some degree of turnover may be desirable in order to replace less effective workers with better ones, the ECCE industry turnover rate in 1990 reached 32.9 percent, considerably above the turnover rate of 11 percent observed among elementary and secondary education teachers. By 2010, however, the gap between the two had narrowed, as turnover from the ECCE industry had declined to 23.6 percent, while turnover from elementary and secondary teaching had remained fairly constant at 10 percent.18 This decline in turnover from the ECCE industry was not just a reflection of secular trends in the economy, as it was sharper than the decline observed among female or low-wage workers. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to look at the evolution of turnover for a nationally representative sample of the ECCE workforce. Estimates of the turnover rate from the elementary and secondary education teaching workforce are computed in the same way as for ECCE workers: we identify, among those who were elementary and secondary education teachers in the calendar year before the survey, the proportion who were no longer so in the week of reference. Teachers are those who were employed in the “elementary and secondary schools” industry and who held occupations as “elementary school teachers” or “secondary school teachers”. 18 24 Second, improvements have taken place within both the center- and home-based sectors, which together account for over eighty percent of the ECCE workforce. Moreover, improvements within home-based child care have been particularly remarkable. To the extent that the characteristics we analyzed are, in fact, good proxies of ECCE quality, our findings would imply a narrowing in the quality gap between home-based and other more formalized types of child care. This is an important finding because as recently as 2005, the home-based sector, historically singled out as the lowest-quality sector within child care, served around forty percent of children under five years whose mothers were employed (U.S. Census Bureau 2005), and there is some evidence that it is the preferred type of arrangement among Hispanic families (Fuller, Holloway and Liang 1996; Liang, Fuller and Singer 2000; Fuller 2008). 25 Figure 1. Evolution of the relative and absolute importance of each ECCE sector over time (1990-2010) Distribution of the ECCE workforce across sectors, 1990-2010 (as a % of all ECCE workers) Number of ECCE workers, by sector (1990-2010) 1,600,000 60 1,400,000 50 1,200,000 40 1,000,000 School-based worker 30 School-based worker 800,000 Center-based worker Center-based worker Home-based worker 20 600,000 Home-based worker 400,000 10 200,000 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 0 26 Figure 2. Evolution of selected characteristics of the ECCE workforce over time, by sector (1990-2010) Share of ECCE workers with at least some college education, by sector, 1990-2009 (as a % of ECCE workers in each sector) Mean hourly earnings of full-year ECCE workers, by sector, 1990-2009 (at 2010 dollars) 20 100 90 80 15 70 60 All ECCE workers 50 School-based worker 40 Center-based workers All ECCE workers 10 School-based worker Center-based worker Home-based workers 30 Home-based worker 5 20 10 Average occupational prestige of workers who moved from a non-ECCE job to the ECCE workforce, in the year before they entered ECCE, by sector that they enter, 1990-2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 0 1992 0 ECCE industry turnover rate by sector, 1990-2010 (% of workers who left the industry from one year to the next) 40 70 60 30 50 ECCE enterers 40 School-based enterers 30 All ECCE workers 20 School-based worker Center-based worker Center-based enterers Home-based worker Home-based enterers 20 10 10 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 2005 2004 2003 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 1996 1995 1994 1993 1992 1991 1990 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 0 27 Table 1. Evolution of the ECCE workforce, and comparison to female and low-wage workers (1990-2010) 1992 2010 2010 vs . 1992 Distribution of the workforce by educational attainment ECCE workers Les s tha n hi gh s chool 21.4 Hi gh s chool degree 31.5 Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree 26.1 At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 20.9 11.5 26.9 33.3 28.4 -9.9 -4.6 7.2 7.5 * * * * Female workers Les s tha n hi gh s chool Hi gh s chool degree Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 11.5 36.0 29.2 23.2 8.1 26.4 31.9 33.6 -3.4 -9.6 2.7 10.4 * * * * Low-wage workers Les s tha n hi gh s chool Hi gh s chool degree Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 20.5 38.9 26.7 13.9 17.0 33.5 31.1 18.4 -3.5 -5.4 4.4 4.5 * * * * 1990 2009 2009 vs . 1990 Mean annual earnings of all workers (at 2010 dollars) ECCE workers 10,746 Female workers 24,427 Low-wage workers 18,266 16,215 30,629 21,298 51% * 25% * 17% * 11.7 19.0 14.2 33% * 17% * 6% * Mean hourly earnings of full-year workers (at 2010 dollars) ECCE workers 8.8 Female workers 16.3 Low-wage workers 13.4 Share of workers with pension and/or health benefits paid at least partly by the employer ECCE workers 19.0 28.0 9.0 * Female workers 56.4 57.9 1.5 * Low-wage workers 42.5 42.2 -0.3 Industry turnover rate ECCE workers Female workers Low-wage workers 1990 2010 32.9 24.7 26.5 23.6 17.9 19.1 2010 vs . 1990 Average occupational prestige in the year before entering the workforce ECCE workforce enterers 37.6 42.3 Low-wage workforce enterers 41.8 42.0 -9.3 * -6.8 * -7.4 * 4.7 0.2 * denotes change with respect to 1990 or 1992 is statistically significantly different from zero at the 5% level. Changes in the share of workers by educational attainment, the share with pension and/or health benefits, and the industry turnover rate are measured in percentage points; changes in annual and hourly earnings, as a percent change; and changes in the average occupational prestige score of those entering the ECCE workforce, in percentiles. Source: Authors based on the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey. 28 Table 2. Evolution of the ECCE workforce by sector (1990-2010) Center-based workers 1992 2010 Distribution of the workforce by educational attainment Les s tha n hi gh s chool 12.3 Hi gh s chool degree 32.7 Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree 33.3 At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 21.6 Home-based workers 1992 2010 School-based workers 1992 2010 9.8 30.0 36.6 23.7 37.6 34.5 21.8 6.1 19.8 * 30.9 34.3 * 15.0 * 5.3 20.6 17.5 56.6 5.1 12.0 * 21.7 61.2 2009 1990 2009 1990 2009 10,809 14,567 * 6,480 12,415 * 24,191 27,014 Mean hourly earnings of full-year workers (at 2010 dollars) 9.2 10.9 * 5.6 8.9 * 17.5 18.2 Share of workers with pension and/or health benefits paid at least partly by the employer 20.4 24.5 3.1 7.6 * 64.3 68.8 1990 2010 1990 2010 1990 2010 Industry turnover rate 34.0 24.4 * 36.9 28.5 * 15.9 13.6 Average occupational prestige in the year before entering the ECCE workforce 41.3 44.6 32.3 33.4 51.4 54.1 1990 Mean annual earnings of all workers (at 2010 dollars) * denotes change with respect to 1990 or 1992 is statistically significantly different from zero at the 5% level. Source: Authors based on the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey. 29 Table 3. Decomposition of the overall changes in the characteristics of the ECCE workforce (1990-2010) Distribution of the workforce by educational attainment Les s tha n hi gh s chool Hi gh s chool degree Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree Change attributable to changes in the characteristics of workers within the sectors Change attributable to changes in the distribution of workers across sectors 2010 vs . 1992 2010 vs . 1992 -8.8 -4.0 7.4 5.4 (65%) (84%) (84%) (58%) 2009 vs . 1990 -4.7 -0.8 1.4 3.9 (35%) (16%) (16%) (42%) 2009 vs . 1990 Mean annual earnings of all workers (at 2010 dollars) 42% (78%) 12% (22%) Mean hourly earnings of full-year workers (at 2010 dollars) 25% (72%) 10% (28%) Share of workers with pension and/or health benefits paid at least partly by the employer 4.3 (48%) 4.7 (52%) 2010 vs . 1990 2010 vs . 1990 Industry turnover rate -8.1 (86%) -1.3 (14%) Average occupational prestige in the year before entering the ECCE workforce 2.1 (49%) 2.1 (51%) Changes in the share of workers by educational attainment, the share with pension and/or health benefits, and the industry turnover rate are measured in percentage points; changes in annual and hourly earnings, as a percent change; and changes in the average occupational prestige score of those entering the ECCE workforce, in percentiles. Source: Authors based on the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey. 30 Table 4. Sector contributions to the part of the change in the ECCE workforce that is explained by changes in the characteristics of workers within the sectors (1990-2010) Center-based workers Home-based workers School-based workers 2010 vs . 1992 Distribution of the workforce by educational attainment Les s tha n hi gh s chool 12% Hi gh s chool degree 28% Some col l ege or As s oci a te's degree 19% At l ea s t a Ba chel or's degree 16% 88% 39% 73% 71% 0% 32% 8% 13% Mean annual earnings of all workers (at 2010 dollars) 37% 2009 vs . 1990 55% 8% Mean hourly earnings of full-year workers (at 2010 dollars) 35% 60% 4% Share of workers with pension and/or health benefits paid at least partly by the employer 41% 45% 14% Industry turnover rate 53% 2010 vs . 1990 44% 4% Average occupational prestige in the year before entering the ECCE workforce 58% 28% 14% Source: Authors based on the March Supplement of the Current Population Survey. 31 REFERENCES Administration for Children and Families. 2010. Compendium of Quality Rating Systems and Evaluations. Prepared by Child Trends and Mathematica Policy Research. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/cc/child care_quality/compendium_qrs/qrs_compendium_final.pdf Barnett, Steven W. 2003. Better teachers, better preschools: Student achievement linked to teacher qualifications. NIEER Preschool Policy Brief 2. Barnett, W. Steven, Dale J. Epstein, Megan E. Carolan, Jen Fitzgerald, Debra J. Ackerman, and Allison H. Friedman. 2010. The State of Preschool 2010. The National Institute for Early Education Research. Available from http://nieer.org/yearbook/pdf/yearbook_executive_summary.pdf Bassok, Daphna. 2010. Do black and Hispanic children benefit more from preschool? Understanding differences in preschool effects across racial groups. Child Development 81 (6): 1828-1845. Bassok, Daphna, Maria Fitzpatrick, and Susanna Loeb. Unpublished manuscript. Disparities in child care availability across communities: Differential reflection of targeted interventions and local demand. Bellm, Dan, and Marcy Whitebook 2006. Roots of decline: How government policy has deeducated teachers of young children. Berkeley, CA: Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. Blau, David. 1999. The effect of child care characteristics on child development. The Journal of Human Resources 34 (4): 786-822. Blau, David. 2000. The production of quality in child care centers: Another look. Applied Developmental Science, Special Issue: The effects of quality care on child development 4 (3): 136-149. Brandon, Richard N., and Ivelisse Martinez-Beck. 2006. Estimating the size and characteristics of the United States early care and education workforce. In M. Zaslow and I. Martinez-Beck (Eds.), Critical issues in early childhood professional development. Baltimore: Brookes. Cost, Quality and Outcomes Study Team. 1995. Cost, quality and outcomes in child care centers: Executive summary. University of Colorado at Denver, Department of Economics, 32 Center for Research in Economic and Social Policy. Currie, Janet, and Matthew Neidell. 2003. Getting inside the black box of Head Start quality: What matters and what doesn’t? NBER Working Paper No. 10091. Early, Diane M., Kelly L. Maxwell, Margaret Burchinal, Soumya Alva, Randall H. Bender, Donna Bryant, Karen Cai, Richard M. Clifford, Caroline Ebanks, James A. Griffin, Gary T. Henry, Carollee Howes, Jeniffer Iriondo-Perez, Hyun-Joo Jeon, Andrew J. Mashburn, Ellen Peisner-Feinberg, Robert C. Pianta, Nathan Vandergrift, Nicholas Zill. 2007. Teachers' education, classroom quality, and young children's academic skills: results from seven studies of preschool programs. Child Development 78 (2): 558-580. Elicker, James, Cheryl Fortner-Wood, and Ilene C. Noppe. 1999. The context of infant attachment in family child care. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 20: 319–336. Fuller, Bruce, Susan D. Holloway, Xiaoyan Liang. 1996. Family selection of child-care centers: The influence of household support, ethnicity, and parental practices. Child Development 67 (6): 3320-3337. Fuller, Bruce, Susanna Loeb, Annelie Strath, and Bidemi Abioseh Carrol. 2004. State formation of the child care sector: Family demand and policy action. Sociology of Education 77: 337-358. Fuller, Bruce. 2008. Standardized Childhood: The Political and Cultural Struggle over Early Education. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Hamre, Bridget K., and Robert C. Pianta. 2006. Student-teacher relationships. In G. G. Bear, & K. M. Minke (Eds.), Children’s Needs III: Development, Prevention and Intervention (pp. 5971). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Harris, Douglas N., and Scott J. Adams. 2007. Understanding the level and causes of teacher turnover: A comparison with other professions. Economics of Education Review 26: 325– 337 Herzenberg, Stephen, Mark Price, and David Bradley. 2005. Losing Ground in Early Childhood Education: Declining Workforce Qualifications in an Expanding Industry, 19792004. Economic Policy Institute. 33 Howes, Carollee, Deborah A. Phillips, and Marcy Whitebook. 1992. Threshold of quality: Implications for the social development of children in center-based child care. Child Development 63: 449-460. Kagan, Sharon Lynn, Kristie Kauerz, and Kate Tarrant. 2008. The Early Care and Education Teaching Workforce at the Fulcrum: An Agenda for Reform. New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Kelley, Pamela, and Gregory Camilli. 2007. The impact of teacher education on outcomes in center-based early childhood education programs: A meta-analysis. NIEER Working Paper. Knudsen, Eric I., James J. Heckman, Judy L. Cameron, and Jack Shonkoff. 2006. Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (27): 10155-10162. Liang, Xiaoyan, Bruce Fuller, and Judith D. Singer. 2000. Ethnic differences in child care selection: The influence of family structure, parental practices, and home language. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 15 (3): 357–384. Mocan, H. Naci, Margaret Burchinal, John R. Morris, and Suzanne W. Helburn. 1995. Models of quality in center child care. In S.W. Helburn (Ed.), Cost, quality and child outcomes in child care centers (Technical Report). University of Colorado at Denver, Department of Economics, Center for Research in Economic and Social Policy. Nam, Charles B. 2000. Comparison of three occupational scales. Unpublished paper. Center for the Study of Population, Florida State University. Nam, Charles B., and Monica Boyd. 2004. Occupational status in 2000: Over a century of census-based measurement. Population Research and Policy Review 23: 327–358. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. 2004. Young children develop in an environment of relationships. Working Paper 1. National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. 2007. The timing and quality of early care experiences combine to shape brain architecture. Working Paper 5. NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. 2000. Characteristics and quality of child care for toddlers and preschoolers. Applied Developmental Psychology 4 (3): 116-135. 34 Peisner-Feinberg, Ellen S., Margaret R. Burchinal, Richard M. Clifford, Mary L. Culkin, Carollee Howes, Sharon Lynn Kagan, and Noreen Yazejian. 2001. The relation of preschool child-care quality to children’s cognitive and social development trajectories through second grade. Child Development 72: 1534-1553. Ronfeldt, Matthew, Hamilton Lankford, Susanna Loeb, and James Wyckoff. 2011. How Teacher Turnover Harms Student Achievement. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17176. Rose, Elizabeth. 2010. The promise of preschool: From Head Start to universal prekindergarten. New York: Oxford University Press. Saluja, Gitanjali, Diane M. Early, and Richard M. Clifford. 2002. Demographic characteristics of early childhood teachers and structural elements of early care and education in the United States. Early Childhood Research and Practice 4: http://ecrp.uiuc.edu/v4n1/saluja.html. Shonkoff, Jack P., and Deborah A. Phillips. 2000. From Neurons to Neighborhoods. The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy of Press. Torquati, Julia C., Helen Raikes, Catherine A. Huddleston-Casas. 2007. Teacher education, motivation, compensation, workplace support, and links to quality of center-based child care and teachers' intention to stay in the early childhood profession. Early childhood research quarterly 22 (2): 261-275. Tout, K., Starr, R., Soli, M., Moodie, S., Kirby, G., & Boller, K. 2010. The child care Quality Rating System assessment: Compendium of Quality Rating Systems and evaluations. Washington, D.C.: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. Tout, K., Zaslow, M., & Berry, D. 2006. Quality and Qualifications: Links Between Professional Development and Quality in Early Care and Education Settings. In M. Zaslow and I. Martinez-Beck (Eds.), Critical issues in early childhood professional development. Baltimore: Brookes. Tran, Henry, and Adam Winsler. 2011. Teacher and center stability and school readiness among low-income, ethnically diverse children in subsidized, center-based child care. Children and Youth Services Review 33 (2011): 2241–2252. 35 U.S. Department of Education, and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2011. Race to the Top – Early Learning Challenge 2011. Guidance and Frequently Asked Questions. Available from http://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetopearlylearningchallenge/guidance-frequently-asked-questions.pdf U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Historical Table. Primary Child Care Arrangements of Preschoolers with Employed Mothers: Selected Years, 1985 to 2010. Available from http://www.census.gov/hhes/child care/data/sipp/index.html. U.S. Census Bureau. 2006. Current Population Survey Design and Methodology. Technical Paper 66. Vandell, Deborah Lowe, and Barbara Wolfe. 2000. Child care quality: Does it matter and does it need to be improved? Institute for Research on Poverty, Special Report 78. Whitebook, Marcy, Laura Sakai, Emily Gerber, and Carollee Howes. 2001. Then and now: Changes in child care staffing, 1994-2000 (Technical Report). Center for the Child Care Workforce, Washington, DC, and Institute of Industrial Relations, University of California, Berkeley. Whitebook, Marcy, and Laura Sakai. 2003. Turnover begets turnover: an examination of job and occupational instability among child care center staff. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 18: 273–293. Whitebook, Marcy, and Sharon Ryan. 2011. Degrees in context: Asking the right questions about preparing skilled and effective teachers of young children. NIEER Preschool Policy Brief 22. 36