Group Work

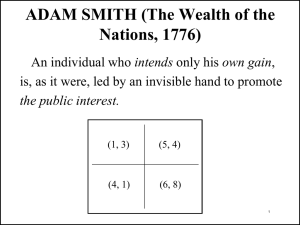

advertisement

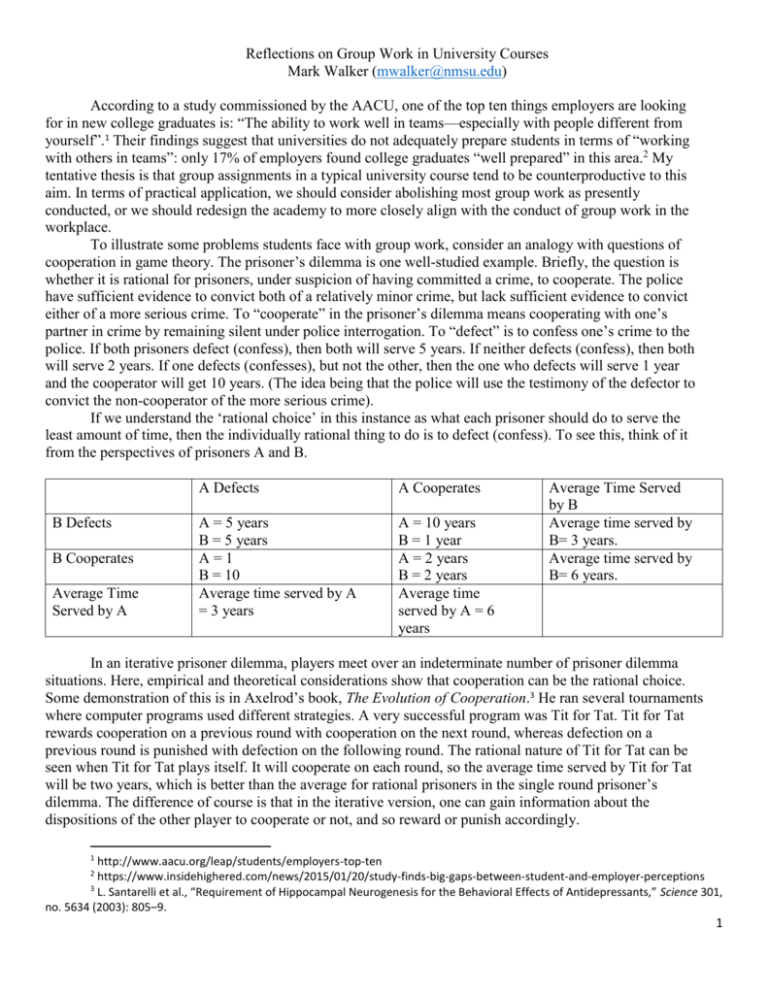

Reflections on Group Work in University Courses Mark Walker (mwalker@nmsu.edu) According to a study commissioned by the AACU, one of the top ten things employers are looking for in new college graduates is: “The ability to work well in teams—especially with people different from yourself”.1 Their findings suggest that universities do not adequately prepare students in terms of “working with others in teams”: only 17% of employers found college graduates “well prepared” in this area.2 My tentative thesis is that group assignments in a typical university course tend to be counterproductive to this aim. In terms of practical application, we should consider abolishing most group work as presently conducted, or we should redesign the academy to more closely align with the conduct of group work in the workplace. To illustrate some problems students face with group work, consider an analogy with questions of cooperation in game theory. The prisoner’s dilemma is one well-studied example. Briefly, the question is whether it is rational for prisoners, under suspicion of having committed a crime, to cooperate. The police have sufficient evidence to convict both of a relatively minor crime, but lack sufficient evidence to convict either of a more serious crime. To “cooperate” in the prisoner’s dilemma means cooperating with one’s partner in crime by remaining silent under police interrogation. To “defect” is to confess one’s crime to the police. If both prisoners defect (confess), then both will serve 5 years. If neither defects (confess), then both will serve 2 years. If one defects (confesses), but not the other, then the one who defects will serve 1 year and the cooperator will get 10 years. (The idea being that the police will use the testimony of the defector to convict the non-cooperator of the more serious crime). If we understand the ‘rational choice’ in this instance as what each prisoner should do to serve the least amount of time, then the individually rational thing to do is to defect (confess). To see this, think of it from the perspectives of prisoners A and B. B Defects B Cooperates Average Time Served by A A Defects A Cooperates A = 5 years B = 5 years A=1 B = 10 Average time served by A = 3 years A = 10 years B = 1 year A = 2 years B = 2 years Average time served by A = 6 years Average Time Served by B Average time served by B= 3 years. Average time served by B= 6 years. In an iterative prisoner dilemma, players meet over an indeterminate number of prisoner dilemma situations. Here, empirical and theoretical considerations show that cooperation can be the rational choice. Some demonstration of this is in Axelrod’s book, The Evolution of Cooperation.3 He ran several tournaments where computer programs used different strategies. A very successful program was Tit for Tat. Tit for Tat rewards cooperation on a previous round with cooperation on the next round, whereas defection on a previous round is punished with defection on the following round. The rational nature of Tit for Tat can be seen when Tit for Tat plays itself. It will cooperate on each round, so the average time served by Tit for Tat will be two years, which is better than the average for rational prisoners in the single round prisoner’s dilemma. The difference of course is that in the iterative version, one can gain information about the dispositions of the other player to cooperate or not, and so reward or punish accordingly. 1 http://www.aacu.org/leap/students/employers-top-ten https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/01/20/study-finds-big-gaps-between-student-and-employer-perceptions 3 L. Santarelli et al., “Requirement of Hippocampal Neurogenesis for the Behavioral Effects of Antidepressants,” Science 301, no. 5634 (2003): 805–9. 2 1 Two questions we should consider: Question 1: Is group work in a standard university course more like a single prisoner’s dilemma or an iterative prisoner’s dilemma? Question 2: Is group work in the typical situation in the workforce more like a single prisoner’s dilemma or an iterative prisoner’s dilemma? The answer to question 1, in the typical case, is a single prisoner’s dilemma. The typical university group project is graded such that everyone in the group gets the same grade, so defectors and cooperators receive the same grade. The notion of ‘defector’ here, of course, designates students who do not do an equal share of the group work. Students often have little information about whether others are defectors or cooperators. There is little opportunity to reward or punish cooperators and defectors. In game theory, the defector in such situations is known as a “free rider”, one who takes the benefit (the grade on the group project) without paying the full cost (equal effort). The answer to question 2, is that group work at a job is more like an iterative prisoner’s dilemma. In a job, workers often work together for several years on multiple projects. A worker who “defects” will often be reported to a supervisor either directly or indirectly. The direct method is where other group members report to the supervisor. (Perhaps just grumbling over the watercooler about Sam the Slacker.) Indirectly, the report may happen when the supervisor asks a worker to choose a team. The supervisor will learn quickly that Sam the Slacker is never chosen as he is a free rider, not a team player. In short, defectors in the work place face punishment in terms of being reported and avoided. A typical example of a free riding problem in a university course is the following description from my daughter’s experience in an NMSU class: The group I was in was composed of myself, two other women, and three men. One of the men rarely showed up to class. We were lucky if he came in once of the three times we met a week. We would constantly text him where we were meeting for the few times we had to do group work out of class, but he never responded. The worst part was the fact that this student was still technically in our class, so we had to attempt to include him in the work when he wasn't there. Despite the fact that there are students who are evidently putting no effort into the class, if they are on the roster, you still have to treat them like a peer or a co-worker. In the real world, this person would be fired. The two other women in my group happened to be friends and spent the entirety of the class giggling. In fact, one of the women started dating one of the men in our group. We would have the entire 50 minute class period three times a week to complete our group work and divvy up the work. Instead, the class would consist of my two group members holding hands and kissing, the other girl on her phone, the one guy not even present, which just left me and one other group member to do all of the work. The new "couple" and the other woman would add a couple of little things to our work and of course sign the sign in sheet, to make it look as though they were contributing. There were only two TAs for the entire class, so clearly they could not keep an eye on everything all at once (why we have one TA for a class of 20 and two for a class of 150 I'll never know). The other man and I spoke on two different occasions to our TAs (as we were not to go to the professor for anything the TA could handle) who said that when grading our group work, they would take a look at it. You can clearly tell from our group work that the majority of the work was written in two people's penmanship as opposed to six. However, we never heard anything of it again. Throughout the semester, the couple and the other woman would assist with the assignments for the first few minutes and contribute a few ideas, only to become more distracted. It did not help that we sat in an auditorium, which is hardly suitable for groups of this size. The couple and the other woman sat in the row in front, while the other man and I sat in the row behind. Every day, the three would turn around and assist with the project for 5 minutes, only to turn back around for the rest of the class period. The other man and I decided to stop spending our energy trying to do the impossible. We figured we would just do our work together and help each other out. As the semester drew to a close, the final exam approached. As was expected, only myself and [X]4 (the only group member who helped) showed up. We worked on our final exam for the two hours, when the professor walked by and said "where is the rest of your group?" When we explained 4 Student’s name has been removed. 2 to her that they did not show up and had not been very helpful during most of our projects, the professor said she would deal with it. However, nothing came of it as far as I know. The man from the "couple" in our group ended up being in [Y extracurricular activity]5 so I knew him after the class. When I spoke to him, he told me he ended up with a B in the class, which was what he was expecting. He received the same grade on the final exam as [X] and I, despite the fact that he wasn't even there and the professor knew this. I am assuming that all of our group members shared our grade. Provided, this is coming from the student rather than the professor, but as the rest of the semester was very similar, I can only assume that the professor did not bother to change their grades, despite the fact that she saw only the two of us working on the final. Survey data on student group work confirms that about a third of students have similar bad experiences: Overall, data from the survey showed that students found group work to provide an ‘average’ experience (m = 3.06, standard deviation (SD) = 1.268), with 44% responding that they had ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ group work experiences (4 and 5 on the Likert scale) and almost a third (32%) responded that they had ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ group work experiences (1 and 2 on the Likert scale). These results were the same across disciplines. 6 The survey data is consistent with the description provided by my daughter. I imagine that she and the other hardworking student would have reported a negative experience. On the other hand, one might imagine that the other four members of the group would have been pleased to do so well in the course given their minimal time investment, so their report would be on the positive end of the scale. What sort of message do we think students glean from their experience in their group work? I suspect that at least some students will internalize the message that free riding in group work is permissible and often rewarded. Thus, we should not be the least bit surprised when employers find new graduates to be ineffective group participants. Suppose we never asked students to work in groups in universities. It might turn out that they actually approach group work with fellow employees with a more cooperative spirit, not having so many negative experiences associated with group work in university. As several authors have warned, we cannot conclude from the free riding phenomena that all free riders are “lazy”. Other explanations have to do with lack of confidence, differences in skills, and extramural obligations (e.g., jobs, children, etc.).7 Perhaps the single biggest contributor may be differences in goals. Many students are looking for only a “C” in a course. Any effort beyond getting a “C” is perceived as an inefficient use of their time. We can predict a priori that there will be problems when we mix students with different grade aspirations into the same group. Yet we do it anyway. Students seeking an “A” will perceive those who are satisfied with a “C” to be free riders. Those who are satisfied with a “C” may think that the “A” seekers are overbearing and inefficient in their time management. Not all of my experiences using group work have been unsuccessful. At NMSU, and at my previous university, I have had occasions where group work has been very successful. Interestingly, in these cases, it was more like an iterative prisoner’s dilemma, since the students working on the group projects were cohorts in elite programs. These students knew that they would be in classes with their group partners in the near future, and they had similar preparation and grade aspirations. In other words, their experience is more like that of group work in an employment setting, rather than in a typical university course. In attempt to address some of these problems, I’ve experimented with effort rubrics. Each student is required to hand in a report of their effort along with the effort of the others in the group. The rubric requires that they estimate, as a percentage, what the others contributed to the project as well as detailing specific tasks, e.g., research, editing, etc. Each individual rubric must add up to 100%. A typical student who says that he or she 5 Extracurricular activity has been deleted in the interest of anonymity. David Hall and Simone Buzwell, “The Problem of Free-Riding in Group Projects: Looking beyond Social Loafing as Reason for Non-Contribution,” Active Learning in Higher Education, 2012, 1469787412467123. 7 Ibid. 6 3 completed 40% of the work might say that one other student did 30% of the work, and that the other two students did 15%. What is interesting is that the self-evaluations tend to add up to more than 100%. For example, when students A, B, C, and D fill out their rubrics, A and B might self-evaluate having completed 40% of the work each, while C and D might self-evaluate at 25% each, for an impressive total of 130%. Football coaches tend to brag that they get 110% effort out of their players: I should go into the lucrative market of coaching because I can often get 130% effort. Certainly some students just make boldface lies on the rubrics. But it also seems plausible to me that students tend to overestimate their own effort and underestimate the effort of others. Indeed, it seems almost certain that students have this bias, given that students tend to be humans. Unfortunately, since the groups disband after the one project, students have little opportunity to correct their judgments. On several occasions, I obtained numbers in the order of 175% effort based on self-evaluation. This required having the students come to my office to sort out the truth. Although the effort rubric improves the free rider situation somewhat, there are at least a couple of serious problems that remain. First, group projects are organic entities. It is hard to evaluate a project even if one knows that one or two students did not pull their weight. Suppose Leonardo and I hand in a group painting, “The Mona Lisa 2”. He spends months painting everything but the eyes and the lips. I add the eyes and the lips in a couple of minutes. Given my lack of effort and artistic talent, the painting as a whole is an abomination, with the eyes and the lips being the most offensive features by far. It is pretty hard to image what it would look like if Leonardo had done the whole thing himself. It would take a policy like ‘no artist left behind’ to get Leonardo into the “B” range on our group project even if I get my well-deserved “F”. Similarly, if a student fails to do adequate research for a group paper, it is hard to assess the effort of the rest. After all, if the research had been done properly, the rest of the paper would have been quite different. More importantly, using the rubrics imposes a certain amount of cooperation; it puts a certain management responsibility on me in terms of monitoring the cooperation of the group. This is not bad in itself, but employers are looking for employees who do not need cooperation to be enforced and monitored. In other words, with the rubrics, I am managing the groups to a certain extent. If the same system is used in the work place, this will put additional management burdens on a company. But this is precisely what employers do not want. They want employees that can work cooperatively without a great investment of supervisory resources. I still have students work in groups, e.g., I ask them to edit their peers’ weekly papers in groups, but they each receive a grade for their own contribution. (I ask them to use different colored pens for editing to keep track of who does what.) However, I do not have them do group projects (other than the aforementioned elite classes.) As far as I can see, there is at least as much reason as not to think that group work tends to instill beliefs and behaviors in students that are not conducive to effective cooperation. If we are serious about hoping to instill the appropriate beliefs and behaviors in students, I think we have to make their education experience more like their prospective employment experience. That is, they ought to be grouped according to preparation and motivation, much like employers hire employees with similar preparation and motivation. Also, working as cohorts over years, rather than a few weeks, ought to be the norm, along with the threat and expectation that a number of students will be “fired”. I don’t see any practical way that we are going to simulate these conditions accurately in the academy we know. But if we are serious about meeting employers’ demands for students who have internalized the beliefs and behaviors of cooperative group members, we should. 4