Acknowledgements & Credits

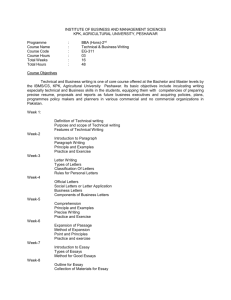

advertisement