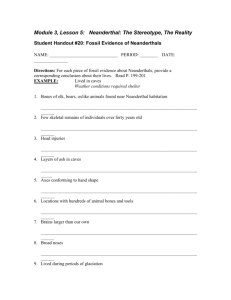

Sermon: Ezekiel 37: 1-14 2014 04 06. Lent 5 Hope and renewal. In

advertisement

Sermon: Ezekiel 37: 1-14 2014 04 06. Lent 5 Hope and renewal. In traditional Maori society, when a child was born, the placenta and the umbilical cord were kept, and at the right time, taken and buried on the home Marae. A hole would be dug, Karakia or prayers said, and the placenta would be buried. The Maori word for the placenta is whenua. Placenta/whenua. It is also the Maori word for land: whenua/land. I looked this, I had always known this, but was not sure if it was not some old tale that was chute but had no real history. But no I’m right, whenua can be translated as “land” and “placenta” According to tradition, a woman, called Papatuanka, inhabits the world under the sea. The lands that appear on the water are placenta from her womb, they become islands. Land/Placenta. Thus Maori, are the people of the land, Tangata whenua, Tangata/people whenua. So the burying of your own placenta into the land of your home Marae, cements a bond between you and the land, a special bond. A deep bond. So it is with pain that Maori lost or alienated their land to the settlers in colonial time, a loss that no amount of compensation can return. This emotional bond between people and their land is a powerful thing across the centuries and across the world is it not. Of the top of my head I was trying to think of examples of this. In my own cultural history there is of course the Highland Clearances, where the great land owners forced the crofters of their land, from their land many had to leave Scotland for good, to Canada, America, Australia and New Zealand. That migration of people from Scotland, contributed to other land migrations. I think of the forced migrations of Native American Indian tribes people, sometimes for hundreds even thousands of miles to new reservations set aside for them, but far from their original lands, this for all the normal colonial reasons, the need for land for the incoming white settlers, a distrust of a people who did not see themselves as under state law and so on. The forced relocation of Aboriginal children, is another, the taking not of their land, a powerful injustice in itself, but the robbing of a people of their future in the land, so that as children they grow up not learning of their warm and rich past, intricately tide up with the land of their ancestors, a deep injustice. And we can think of others, many many others I am sure. What I want to show by these examples and the others that you might be aware of is the deep feelings that loss of land leave or generate in people, how such loss can leave whole peoples intergenerational affected, just the great sense of loss, how hope can be extinguished. Bleak depression results. Page 1 of 3 Sermon: Ezekiel 37: 1-14 2014 04 06. Lent 5 Hope and renewal. So if we understand that, or even at least catch a glimpse of that despair, then we are along the path of understanding what is the deep feelings behind this amazing story we have read this morning. The story of the valley of the dry bones. So this vision, this story is a story about land. The setting of the story or vision is in the first few years after the people had be taken from Palestine, Israel and Judah, and removed, marched to the Euphrates and Tigris valley, or in other words: Babylon. They were severed from their land, cut of, gone were their historic links, and gone indeed many felt was their very life and future, because God was so much bound up in that land, the promised land, that they felt that the promise had failed, God had failed, they were dry bones in a dry land. So into this place of failure, hopelessness and loss, comes this marvelous world of God. These bones can have life, sinews and flesh can return to them, and breath can be breathed on them and as God says” I will place you on your own soil, and you shall know that I the Lord have spoken and can act.” So the vision of the dry bones coming to life was a vision of hope for an exiled people, who would be restored to their land, returned to their home, and in so doing find life. It is a profound message of hope. What I have struggled with over the last few days as I have read this, and reflected on the history of this passage in our culture, the image of bones, of life in death and so on, wondering all the time, what is the message here for us. We are not displaced, landless, exiles. Is there a word for us in this story. We can see this story as it were from afar, we can enter into the feelings of the displaced people, by remembering the stories of displacement that we are familiar with, like the Scottish clearances, the American Indian migrations, the Maori land confiscations of the 19th century, but these, difficult and emotional as they are, are not our stories, so what is this story for us. There are ways of looking at this passage, it’s context in Lent, looks forward obviously to the resurrection, and so it is linked in the Lectionary with the story about Lazarus. So that helps, here is a story about resurrection, about bodies coming to life and so on. But there is a danger in this, in that the dry bones passage becomes spiritualized and individualized, but that was not its original context, this is a story about a community finding life, a community coming back from the dead, a community returning to it places of birth and finding life. So I find this story a challenge. For the story is about God acting, God bringing the community back to life, about God’s sovereignty and power. Page 2 of 3 Sermon: Ezekiel 37: 1-14 2014 04 06. Lent 5 Hope and renewal. Can dry bones live. Can communities given over to violence and despair live, can communities lost in oppression and hopelessness live, can peoples who have lost their way live, can what is dry and worthless live. The prophet says yes, hope is not lost, new visions, new ways can grow up, people can be renewed, we do not need to live constantly under a cloud a despair, because life and love and grace will out, God will bring this about in a thousand different ways that echo the thousands of dry bones in the valley. Many years ago now on the outer island of Iona in the Scottish Hebrides, George McLeod looked at the ruined bones of the Iona Cathedral Abby buildings and asked that very question, can these bones live. He had a vision of people, Christians and others working together to restore the Abby, and by doing so renewing the Scottish church and the poor community from Glasgow that he came from. In many ways, but different from the return of Israel from exile, but similar, that vision has been realized. The Abby stands, a community focused on renewal and justice is founded there, many folk from the community work around the world in areas of justice and the church has benefited from his vision and work. But if you had stood alongside him on that day on Iona, you may have thought him mad, can these bones live. No. But with God nothing is impossible. The same God is with us in this place. Nothing is impossible. Can these bones live? You bet they can. Page 3 of 3