Probative value - the United Nations

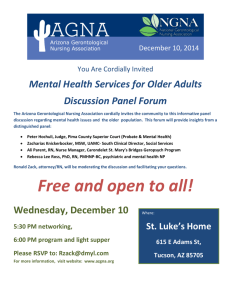

advertisement