PROVIDING REDUCTIONS IN GENDER BULLYING IN K-3 USING THE

SECOND STEP: A VIOLENCE PREVENTION CURRICULUM

Ann Munsee

B.A., California State University, Humboldt, 1991

PROJECT

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

EDUCATION

(Gender Equity Studies)

at

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO

SPRING

2010

PROVIDING REDUCTIONS IN GENDER BULLYING IN K-3 USING THE

SECOND STEP: A VIOLENCE PREVENTION CURRICULUM

A Project

by

Ann Munsee

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Frank R. Lilly, Ph.D.

____________________________

Date

ii

Student: Ann Munsee

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the

University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library

and credit is to be awarded for the Project.

, Associate Chair

Rita M. Johnson, Ed.D.

Date

Department of Teacher Education

iii

Abstract

of

PROVIDING REDUCTIONS IN GENDER BULLYING IN K-3 USING THE

SECOND STEP: A VIOLENCE PREVENTION CURRICULUM

by

Ann Munsee

Statement of Problem

The Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum (Committee for Children,

2005) lacks a gendered harassment component. According to Harris Interactive and

Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network, the absence of gender is problematic.

For students, the second and third most reported forms of harassment are related to

their perceived or actual sexual orientation and their measure of masculinity or

femininity. Aside from the high incidence of occurrence, gendered harassment has

been linked to school-site violence. Kimmel and Mahler (2003) analyzed school

shootings and found that all of the perpetrators reported being victims of homophobic

harassment. In addition to physical violence, gendered harassment has caused social

and psychological problems. Students who were harassed due to gender expression

reported feeling disconnected and unsafe at school. This often resulted in attendance

problems and lower academic achievement. Depression and suicidal thoughts and

plans doubled for students who were harassed based on their actual or perceived

iv

sexual orientation (California Safe Schools Coalition & University of California

Davis, 4-H Center for Youth Development, 2004). The reinforcement of traditional

gender norms is often a motive of gendered harassment (Kimmel & Mahler, 2003;

Pollack, 1999). The enforcement of traditional gender roles reduces honest selfexpression, inhibits the ability for girls and boys to fully develop an authentic self

(Brown, Chesney-Lind, & Stein, 2007) and maintains the hierarchal structure of males

holding power over females (Epstein, 2001; Meyer, 2006).

Sources of Data

An outcome of the project was lessons developed to address gendered

harassment. The three lessons are: Lesson One: Respecting Diversity; Lesson Two:

Name-Calling; and Lesson Three: Gender-Biased Comments. The lessons are

designed for elementary schools that have adopted the 2002 Second Step: A Violence

Prevention (SSAVP) curriculum distributed by Committee for Children (2005).

Specifically, the lessons are an addendum to be used with the second grade SSAVP

curriculum kit, at Del Paso Manor Elementary School in the San Juan Unified School

District, Sacramento, California. The lessons are scripted, follow the same format and

incorporate the same teaching strategies as SSAVP.

Conclusions Reached

A review of the literature suggested key elements to be incorporated into antibullying lessons in order to prevent future incidences of gendered harassment.

Respecting diversity, eliminating name-calling and responding to sexist comments

v

were recommendations found throughout the literature. In order to address gendered

harassment, teachers need to be prepared and provided with lessons, curriculum and

training. The three lessons created are a starting point for the second grade teachers at

Del Paso Manor Elementary School to begin to address the problem of gendered

harassment in schools.

, Committee Chair

Frank R. Lilly, Ph.D.

_______________________

Date

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1

Purpose of the Project ....................................................................................... 1

Statement of the Problem ................................................................................. 2

Significance of the Project................................................................................ 4

Definition of Terms .......................................................................................... 5

2. REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE ........................................................... 7

Introduction ...................................................................................................... 7

Theories of Gender Development .................................................................... 7

Theories Related to Gendered Harassment .................................................... 10

Absence of Gender in Elementary Anti-Bullying Curriculums ..................... 18

Reasons for Addressing Gendered Harassment in Elementary School .......... 21

The Link Between Gendered Harassment and School Violence .................... 22

Teacher Responses to Gendered Harassment ................................................. 22

Ill-Equipped Teachers .................................................................................... 23

Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 23

3. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 25

Setting ............................................................................................................. 25

Participants ..................................................................................................... 25

vii

Instruments ..................................................................................................... 25

Design ............................................................................................................. 26

Procedures ...................................................................................................... 28

4. DISCUSSION....................................................................................................... 29

Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 29

Limitations ...................................................................................................... 29

Recommendations .......................................................................................... 30

Appendix. Lesson Plans ........................................................................................... 33

References .................................................................................................................. 41

viii

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Purpose of the Project

The intent of this project is to analyze the types and probable causes of

gendered harassment and to create age appropriate lessons to combat gendered

harassment for early elementary students aged six to eight years. The lessons included

as part of this project are designed for use with the 2002 Second Step: A Violence

Prevention Curriculum (SSVPC) currently being implemented in the San Juan Unified

School District, in Sacramento, California. Currently, the SSVPC does not directly

address gendered harassment. The project’s three lessons address the gender related

issues of: diversity acceptance, name-calling, and gender-biased comments to be used

with the SSVPC for grade two.

The California State Legislature has mandated that a school environment free

of gender-based discrimination is a right that all students share. The California

Education Code, Article 3, Prohibition of Discrimination, Section 220, extends the

hate crimes law, Section 422.55 of the Penal Code, into the schools. The code states

that no person shall be discriminated against due to disability, gender, nationality,

race, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation. The California Student Safety and

Violence Prevention Act, AB 537 (2000) extends protections against discrimination

for students and staff as a result of perceived or actual sexual orientation or gender

identity. In 2007, additional legislation was passed. The Safe Place to Learn Act, AB

394, provides information and guidance to school districts and the California

2

Department of Education to fully enact AB 537. Additionally, the Student Civil Rights

Act, SB 777 (2008), updates all former antidiscrimination laws in the public schools to

include the most current categories of discrimination. In order to reduce or eliminate

harassment and discrimination against students based on their gender identity, gender

expression and actual or perceived sexual orientation, lessons have developed to be

used with the second grade Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum.

Statement of the Problem

The Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum lacks a gendered

harassment component. The omission of gender is problematic because the second and

third most common forms of harassment reported by students is related to their

perceived or actual sexual orientation and their measure of masculinity or femininity.

These two forms of harassment are only second to harassment based on appearance

(Harris Interactive & Gay Lesbian Straight Education Network, 2005). The incidence

of harassment related to perceived or actual sexual orientation has increased most

significantly when compared to other forms of sexual harassment according to data

that has been gathered since 1993. In 1993, 51% of students reported knowing

someone who had been called gay or lesbian as compared to 61% in 2001. This is a

powerful statistic considering that most of the other forms of sexual harassment either

have remained the same or have decreased (Harris Interactive for American

Association of University Women Educational Foundation, 2001).

The absence of gender issues in anti-bullying curriculums is particularly

alarming due to recent research that has demonstrated a link between school violence

3

and gendered harassment. Specifically, research shows that harassment related to

gender is more likely to result in violence. An analysis of school shootings found that

all of the school shooters reported being victims of homophobic harassment (Kimmel

& Mahler, 2003). Researchers believe that ignoring the relationship between gendered

harassment and violence prevents schools from creating curriculum that can be used as

an effective tool to end school violence (Kimmel & Mahler; Stein, 2007). In addition

to the high correlation between gendered harassment and the incidence of school-site

violence, researchers have also identified lower academic achievement as an outcome

related to gendered harassment. Harassed students feel unsafe and disconnected from

school, factors that likely contribute to attendance problems and lower academic

achievement. Depression and suicidal plans and thoughts double for students who are

harassed based on actual or perceived sexual orientation compared to students who are

not (California Safe Schools Coalition & University of California Davis, 4-H Center

for Youth Development, 2004).

Gendered harassment is often carried out to reinforce traditional gender norms

(Kimmel & Mahler, 2003; Pollack, 1999). Encouraging traditional gender roles

reduces honest self-expression and inhibits the ability of each child to fully develop an

authentic self. In an effort to conform to traditional female norms, girls minimize their

contributions in the classroom, which often leads to feelings of loss of control and

invisibility (Brown, Chesney-Lind, & Stein, 2007). Boys, on the other hand, are

expected to express masculinity by acting tough and in charge regardless of how they

really feel (Pollack). Reinforcing masculinity for boys and femininity for girls can

4

have negative consequences for both sexes (Rivers, Duncan, & Besag, 2007), but girls

are more often harassed because of their gender than are boys (Harris Interactive &

GLSEN, 2005). In addition, Young and Sweeting (2004) reported that femininity is

associated with negative self-esteem in girls whereas masculinity is associated with

high self-esteem for both girls and boys. The lower status associated with being a

young female (Powlishta, 2000) increases the incidence of depression in adolescent

girls (Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994).

Significance of the Project

In California, legislation was proposed in 2009 that mandates schools to

actively and seriously respond to students who are harassed based on their gender

expression and sexual orientation. The proposed legislation has not yet been signed

into law and, as of April 2010, there is no Senate bill pending. The Safe Schools

Improvement Act, H.R. 2262, would require schools and districts to create codes of

conduct prohibiting bullying and harassment, including bullying and harassment based

on sexual orientation and gender identity. Nationally, there is a bill in Congress called

The Student Nondiscrimination Act of 2010, HR 4530. This bill would end

discrimination based on actual or perceived sexual orientation, gender identity, much

like the Civil Rights Act did for racial discrimination, and Title IX did to address

discrimination based on gender. It has yet to be signed into law. Without legal codes

of conduct for schools to address harassment, it seems critical that lessons and

curriculums be developed and implemented to address and reduce gendered

harassment in schools.

5

Definition of Terms

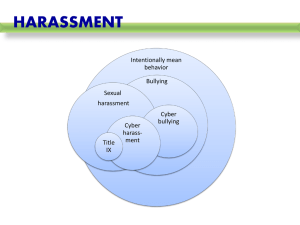

There are three primary characteristics that describe bullying behavior:

aggressive behavior with intent to harm, repeated and over time and an imbalance of

power (Olweus, 1999, part I). Bullying is currently addressed in elementary school

curriculums; however, bullying that is specifically related to gender is absent from

most of the curriculums written for elementary schools. Meyer (2006) defines

gendered harassment as, “any behaviour that serves to police and reinforce the

traditional gender roles of heterosexual masculinity and femininity, such as bullying,

name-calling, social ostracism and acts of violence” (p. 43). Harassment due to nonconforming gendered expression, harassment rooted in homophobic feelings, and

harassment designed to reinforce traditional gender roles are all components of

gendered harassment.

Meyers (2006) feels an important first step in addressing gendered harassment

is to first understand the behaviors that characterize the three types of harassment:

harassment based on non-conforming gender expression, homophobic harassment, and

heterosexual harassment. Harassment based on non-conforming gender expression is

harassment targeted at people due to behaviors that are perceived as not conforming to

traditional notions of gender identification. Homophobic harassment includes

negative, hostile, or threatening behavior that is directed toward gay, lesbian, bisexual,

or transgendered people. Heterosexual harassment is sexual harassment designed to

reinforce traditional heterosexual gender roles (Meyer). The term bullying was

deliberately replaced with harassment for reasons explained in Chapter 2.

6

Gender is related to different social constructs. The University of California at

Berkeley Gender Equity Resource Center (2010) provides definitions of terms related

to gender. The first term is gender. Gender is a socially created system that assigns

qualities of masculinity and femininity to people. Gender characteristics are fluid, can

evolve over time, and are different between cultures.

The term gender identity refers to the gender that people perceive themselves

as. This also includes people who refuse to use gender to label themselves. Gender

identity is often inaccurately associated with sexual orientation; however, gender

identity is not indicative of sexual orientation. In other words, a feminine man is not

necessarily a gay man.

Gender non-conforming or gender variant is to display nontraditional gender

traits that are not typically associated with the person’s biological sex. An example is

masculine behavior or appearance in a female. Culture determines what is considered

nonconforming or variant.

Sex is a term used to define a person based on their biological anatomy and

chromosomes. Although sex is considered biologically determined, social ideas and

views about a person’s sex create cultural influences as well.

Gender roles are masculine and feminine expectations of a person based on

their biological sex. The social and cultural norms that are associated with being male

or female influence the way people behave.

7

Chapter 2

REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE

Introduction

The key areas of research explored for this project were gender and harassment

or bullying. Within those broad concepts, the focus narrowed to investigate the

research specifically related to gender and its role in harassment or bullying. The

review of literature began with the two main theories of gender development:

socialization theory and evolutionary theory. Research was then conducted on the

three types of gendered harassment and how they are manifested in schools:

homophobic harassment, harassment based on non-conforming gender expression, and

heterosexual harassment. An absence of information related to addressing gendered

harassment in elementary schools led to research to find out about the absence. The

final area of research covered for this project was to highlight the reasons gendered

harassment should be addressed in early elementary school.

Theories of Gender Development

Socialization Theory

Understanding the main theories of gender development is important for

addressing gendered harassment. There are two main theories of gender development:

socialization theory and evolutionary theory. The socialization theory states that

gender identification occurs as a result of a process of socialization that begins

primarily within the family structure and then expands outward to include additional

environmental influences (Cherlin, 1996). Socialization theory relies on the idea that

8

gender identification is a learned behavior and therefore comes from a cognitive

function. In other words, as opposed to evolutionary theory that emanates from a

biological determinist perspective described later in this chapter, socialization theory

relies on the ability of children to learn. Initially using perception to categorize, the

ability to identify gender by category is cemented once language acquisition occurs.

Socialization during childhood, as it relates to gender, is seen as a way to

prepare children for their roles as adults, supporting children’s development as they

integrate into the culture within which gender norms are contextualized (Maccoby,

1998). Maccoby notes there are two distinct means through which socialization

occurs, direct socialization and indirect socialization. Direct socialization is

characterized by direct teaching, which uses positive and negative reinforcement to

illicit desirable behaviors. Indirect socialization involves learning through observation

and modeling, also known as self-socialization. The self-socialization hypothesis

suggests that in addition to external social pressures, children initiate their own gender

identification and then integrate the socialization process with that self-initiated

understanding of gender in order to render their own interpretations of gender

(Maccoby).

Thorne (1993) was influential in challenging the limitations of the socialization

theory based on her studies of gender development in elementary school classrooms.

Thorne’s research led her to suggest that children are more active participants in their

gender development than prior gender socialization and gender development theorists

allowed for. Socialization theory assumes that the social pressures put upon children

9

create definitions of gender, reinforcing stereotypical masculine or feminine traits in

children as if the children were not living their own lives. The assumption of

socialization theory includes the notion that children are responding to the influence of

adults, rather than relying on any other gender-identification markers that may

emanate from their independent experiences as individuals.

Research conducted by Jacklin and Maccoby (1978) illustrates additional

shortcomings to the theory of socialization. Jacklin and Maccoby’s research shows

that gender behavior is affected by the gender of the group in which the interaction is

taking place. Jacklin and Maccoby’s work is related to Judith Harris’ (1995) theory of

group socialization. Harris’ theory suggests that parents socialize their children who in

turn socialize other children. Children maintain the behaviors they were taught and

eliminate or modify behaviors not accepted by their peer groups (Harris).

Evolutionary Theory

A second theory related to gender development in children is evolutionary

theory, which arises from the notion that there is a biological component to gender

identification. Maccoby’s (1998) explanation is that evolutionary theory treats male

and female children as subspecies for whom gender identification is viewed in the

context of which traits are most successful for the evolution of the species. In this

sense, gender identification is based on the idea that individuals within the subspecies,

as well as the subspecies as a group, will adapt behaviors that “maximize each

individual’s inclusive fitness” (p. 95). The definition of inclusive fitness is tied to the

theory that only those traits and characteristics that allow the species to continue and

10

develop are valued. Hence, for men, the priority is impregnating as many females as

possible; and for women, the value is based on child rearing so that children mature

into adulthood and grow the species. Characteristics that support these goals, which

are based on gender identification, are then valued and reinforced by the group

through play and within the context of group interactions (Maccoby).

Gender development theories are important to consider given the target age of

the children this project seeks to address, six to eight years of age. A key factor is this

age group’s preference for same sex play. This preference begins around the age of

three and becomes strongest by the ages of eight to eleven (Maccoby, 1998). Another

factor is the influence of peer groups on gender development (Harris, 1995). Also of

note is Thorne’s (1993) suggestion that children play an active role in their own

gender development. In addition to understanding the way children learn, or express

gender, is the need to understand harassment related to gender issues.

Theories Related to Gendered Harassment

Moral Disengagement Theory

Moral disengagement theory is one useful context to consider when analyzing

gendered harassment. According to the theory of moral disengagement, perpetrators

justify the violence against victims by identifying the victims as threats to strict

societal gender norms. This process of rationalizing their behavior includes justifying

the perpetrator’s deviant behavior, ignoring or minimizing the effects of the actions of

the perpetrator on the victim, and engaging in acts that dehumanize the victim and

assign blame to the victim. Blaming and dehumanizing the victim has the most

11

powerful impact on victims when compared to all the other aspects of moral

disengagement. It was found that males had a higher rate of disengagement when

compared to females. (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996).

Downward Comparison Theory

Downward comparison theory is based on the principle that people can

improve their feelings about themselves by comparing themselves with people less

fortunate. Downward comparison can function as a means to elevate self-feelings for

someone who has been socially weakened. This sometimes occurs at the expense

another less fortunate person (Wills, 1981). Downward comparison behaviors can be

elevated in a competitive school environment. Students in competition to be the best

may aggressively pursue their high academic or social status at the expense of other

students. In cases where social status is weakened or threatened, a student may strike

out against another student, often with the use of verbal or physical attacks (Rivers et

al., 2007).

Attachment Theory

Gendered harassment can also be viewed through Tharinger’s (2008) work on

attachment theory as explicated by Bowlby (1980). Bowlby believes humans rely on

an innate attachment, particularly during times of stress or fear. This attachment

increases the instance of survival by promoting close proximity to caregivers, thus

increasing safety. Tharinger broadens the attachment theory by extending it outside of

the familial realm and applying it to all significant relationships. When specifically

looking at adolescents and attachment, the fear of peer and societal rejection can be

12

devastating. Being rejected or perceived outside the norm can sometimes result in

violence due to pressure to strike out against those who reject or may reject

(Tharinger).

A study analyzing interviews of boys, ages 11 to 14 years old, found that boys

have a fear of being laughed at and will go to great lengths to suppress their true

feelings. The authors of this study note the connection between the boys’ fear of

laughter directed at them and the resultant use of violence (Phoenix, Frosh, &

Pattman, 2003). Additionally, Pollack (1999) correlates the existence of violence to

the feelings of disconnection experienced by boys. He suggested that boys use

violence to ward off shame. They use violence as an offensive tactic, hurting others

who may potentially hurt them or hurting others to gain social status.

Perceptions of gender identification can be a reason children are rejected.

Boys, in particular, participate in gauging and monitoring each other’s behavior and if

the behavior is perceived as too feminine, then the boys respond with bullying in order

to reduce or eliminate the feminine behavior (Nayak & Kehily, 1996). Young and

Sweeting (2004) found that gender atypical boys were twice as likely to be victimized

by bullies and were more likely to report feelings of loneliness.

Concept of Homophily

Gendered harassment that occurs regularly among friends can be evaluated by

looking at a term called Homophily. In 1954, Lazarsfeld and Merton coined the term

homophily to name the tendency for friendships to develop between people who are

alike. Kandel (1978) looked further at homophily and found that homophily is equally

13

affected by both peer selection and peer socialization. In other words, friends choose

each other because of their similarities as well as remain or become more similar once

they are friends. Poteat (2008) looked at peer groups and their use of homophobic

epithets. He found that the homophily hypothesis indeed holds true when analyzing

the use of homophobic epithets (e.g., faggot). Individuals who use homophobic

epithets are likely to have friends who do the same. When aggression is added to the

peer group, the use of epithets increases.

Manifestations of Gendered Harassment

Homophobic harassment. Boys routinely describe incidences involving the

regular use of homophobic epithets within peer groups (Plummer, 2001). As early as

primary school, the use of homophobic epithets begins. This occurs before sexual

maturity and often lacks sexual meaning. There are many examples in the literature of

boys calling each other gay, homo or fag. Kimmel and Mahler (2003) have termed this

type of bullying as gay-baiting. Gay-baiting is the use of homophobic epithets to

regulate behavior, not necessarily due to the fact that the victims are gay or perceived

to be gay but because the victims do not demonstrate typical masculine behaviors. For

example, if a boy exhibits feminine behavior that creates discomfort in other boys,

calling that person gay targets the undesirable behavior. This process is used to define

acceptable behavioral norms within the peer group (Nayak & Kehily 1996; Phoenix et

al., 2003; Plummer, 2001). Gendered or homophobic harassment is often characterized

by this type of social banter and is usually considered socially acceptable (Franklin,

2000; Phoenix et al., 2003).

14

Plummer (2001) stated that, “Homophobia precedes and presumably provides

an important context for subsequent adult sexual identity formation for all men” (p.

22). He reported that boys consistently claim that homophobic epithets were the worst

thing to be called and not easily forgotten. Although the use of homophobic epithets

seems acceptably common, it is linked with increased aggression involving both males

and females (Poteat & Espelage, 2005). Boys who are harassed by being called gay, as

opposed to boys harassed for other reasons, have more negative feelings about their

school climate, have stronger feelings of anxiety and depression, and are harassed with

more verbal and physical aggression (Poteat & Espelage, 2005; Swearer, Turner,

Givens, & Pollack, 2008). This was true for lesbians and gays as well (Poteat, 2008;

Rivers, 2001).

Homophobic harassment is also a reality for girls. To a lesser degree than boys,

girls use homophobic epithets in an aggressive manner (Poteat & Espelage, 2005).

Young and Sweeting (2004) found that gender atypical girls were almost twice as

likely to be victimized as their gender typical peers were. Among 15-year-old girls,

attributes associated with being unpopular were, “being a lesbian, having special

needs, and being quiet” (Duncan, 2006, p. 53).

Harassment Based on Non-Conforming Gender Expression

Research results suggest that when boys’ masculinity and heterosexuality are

threatened they are likely to participate in homophobic harassment (Phoenix et al.,

2003). A strong masculine self is identified as a heterosexual male (Kimmel, 1994).

There is tremendous pressure for men to be perceived as masculine in order to also be

15

perceived as heterosexual. Through qualitative interviews of parents of preschoolers,

Kane (2006) found that seven of 27 heterosexual parents made assumptions about

their son’s nonconforming gender behaviors as indications of their son’s possible

homosexuality. This was not true for parents of daughters or for gay and lesbian

parents. Kane (2006) suggests “how closely gender conformity and heterosexuality are

linked within hegemonic constructions of masculinity” (p. 163). Any behavior that is

not perceived as masculine threatens a male’s identity as a heterosexual (Pollack,

1999).

Heterosexual Harassment

Masculinity. In his book, Pollack (1999) claims that boys are bound by a

gender straightjacket, meaning that they are bound by the traditional traits associated

with masculinity. Boys are expected to act tough, suppress their feelings, and take

charge. This gender straightjacket becomes even more pronounced during middle

school. Pollack writes of the pressure for boys to be cool at this age. In many

instances, boys equate being cool with being masculine.

Study participants responded negatively when presented with examples of

deviations from masculine gender roles, reinforcing the idea that males are bound by a

rigid code of masculinity (Levy, Taylor, & Gelman, 1995; Martin, 1990). This

hypermasculinity sets up a culture ripe for harassment. All students suffer as a result

of an oppressive culture that sets up a norm where children suppress an authentic

expression of self for fear of being victimized (Rivers et al., 2007).

16

Femininity. The social pressure to conform to gender and sexual norms is not

limited to males. Kane’s (2006) study found that although males have a greater

pressure at an earlier age, females are under pressure to exhibit just the right amount

of femininity as they emerge from puberty. Parents of girls responded negatively to

girls whose appearance was identified as too feminine or too masculine. Although

females are encouraged to try masculine activities when they are young, once puberty

hits, social expectations change (Pipher, 1994). As they grow into adolescence, girls

feel more pressure to reinforce their femininity (Sadker & Sadker, 1994; Thorne,

1993).

Young and Sweeting (2004) found that self-esteem was negatively related to

femininity within girls whereas masculinity within both boys and girls had a positive

relationship to self-esteem. Women and feminine qualities such as nurturance,

cooperation and intuition are not valued in our culture (Orenstein, 1994). Reinforcing

traditional gender roles does no favor to female students. The lower status of female

and child (Powlishta, 2000) combine to cause reason for depression in early

adolescence for young females (Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994; Sadker & Sadker,

1994). In response to an essay prompt related to what it would be like to be the

opposite gender, 42% of girls made positive associations with being male, while only

5% of boys made positive associations with being female (Sadker & Sadker).

Duncan (2006) conducted a study in England with 15-year-old girls and found

that girls associated popularity with “being popular with boys, being loud and being

fashionable” (p. 53). Girls are expected to look, dress and conform to the particular

17

fashion norms of the school, as dictated by the popular girls, in order to be accepted by

their peers and those who set the social pecking order (Rivers et al., 2007). Duncan

found that popularity for girls involves girls’ controlling other girls’ social affairs and

also their willingness to physically fight in order to maintain control and power, a

perfect example of hegemony (Duncan).

Girls are also frequently harassed for issues related to their sexual morality,

often being called derogatory names such as whore, ho, or slut. Girls’ current avenue

to attain social power is through engaging in objectifying behaviors (Brown et al.,

2007). De Beauvoir (1952) writes of women’s futures being dependent on sexual

relationships with men. The number one contributing factor to an adolescent girl’s self

worth is her physical appearance (Orenstein, 1994) particularly habits and behaviors

related to attention from boys (Orenstein; Sadker & Sadker, 1994; Thorne, 1993.

Based on gender alone, girls are more likely to be harassed than boys are (Harris

Interactive & GLSEN, 2005).

In order to gain social status, girls often minimize their contributions. This

leaves girls to feel invisible and to feel a loss of control (Brown et al., 2007). Sadker

and Sadker (1994) interviewed and observed students in schools for 25 years. Their

findings related to girls in schools are significant. As girls mature into adolescence,

they lose their confidence, their sense of selves and their voices. Time and time again,

teachers were observed facilitating problem solving experiences for boys and

reversely, solving problems for girls. Overt sexist comments by teachers regarding

girls’ inadequacies were reported. Girls internalized the message that they were

18

incapable. They were ostracized for being intelligent and responded by hiding their

intelligence and becoming increasingly invisible. “Like a thief in school, sexist lessons

subvert education, twisting it into a system of socialization that robs potential” (Sadker

& Sadker, p. 13).

De Beauvoir (1952) characterizes girls’ adolescence as tragic. She states that at

a time when girls have the urge to explore and conquer, they learn to be silent and

passive. In school and in life, girls and women often feel unsure, inadequate, and

insecure. They begin to second guess themselves, diminish their accomplishments, and

take themselves out of academic and public discourse (Orenstein, 1994).

Absence of Gender in Elementary Anti-Bullying Curriculums

The Conflation of Gender Expression and Sexuality

The assumption that is often made between gender and sexuality has kept

gender out of the anti-bullying curriculums in elementary schools. Schools seem

unwilling to address gendered harassment because of the tie between gender and

sexuality (Leach & Mitchell, 2006). Gender nonconformity is often associated with

homosexuality (Kimmel & Mahler, 2003; Meyer, 2006) because people often perceive

gender expression, sexual orientation, and appearance to be determinate of each other

(Harris Interactive & GLSEN, 2005). If an anti-gendered bullying curriculum is

challenging traditional gender norms it seems as if the idea of homosexuality could

hardly be absent from the curriculum. When heterosexuality is the only model offered

to students in schools (Nayak & Kehily, 1996), education related to homosexuality is

almost nonexistent. With the strong heternormativity culture in the United States

19

(Espelage & Swearer, 2008) it is unlikely that many school districts would approve a

discussion on homosexuality in elementary school.

The Alameda Unified School District in California (2010) is in the process of

adopting lessons to address lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT)

harassment. The Board of Education has approved a series of lessons, referred to as

Lesson 9; however, some parents in the district reacted by requesting that their

students be excused from the lessons, much like the legal excuse from sex education

lessons. A judge ruled that parents did not have the right to have their children

excused due to the fact that the lessons do not include any form of sex education.

Parents also claimed that singling out LGBT issues was unfair and that all areas of

discrimination should be addressed with equal time. The school district has since

collected and made available books and resources available for public review in order

to address the other areas of discrimination. Final adoption of materials and lessons

are pending (Alameda Unified School District).

San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) in California is a unique

district. The district led the way as the first district in the nation with curriculum,

resources and trainings to support gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender or

questioning (LGBQT) students (Norton, 2010). In 1990, the SFUSD Board of

Education approved implementation of a program, Support Services for Gay Youth

that provided counseling services to LGBTQ high school students. Two years later,

the program expanded to offer the same services to students, families, and staff

throughout the district. Shortly thereafter, in 1996, the School Board passed Board

20

Resolution #610-8A6 that mandated program changes within Support Services for

LGBTQ. The changes included expanding curriculum, increasing educational

materials, implementation of the Anti-Slur Policy, and providing professional

development for all staff related to meeting the needs of LGBTQ students. Later,

board resolution #5163 provided added support for transgender staff and students (San

Francisco Unified School District website, 2010). Clearly, San Francisco Unified

School District is a pioneer in the area of LGBQT support.

Legal Implications of Harassment Versus Bullying

Gender has also been absent from most bullying curriculums because of the

legal ramifications of gender or sexual harassment. If a student is being bullied the

laws do not protect the student in the same way as if the student was being harassed.

Stein (2003) believes that the intertwining of the terms bullying and harassment has

played a part in the lack of serious response to gender related incidences in schools.

Stein asserts that bad behavior is categorized as bullying, when in fact it may be illegal

sexual or gender harassment, hazing or assault (Stein, 2003). For curriculum geared

towards young children, Stein (2007) suggests that the term bullying is appropriate

because they do not understand sexual harassment or violence. In an interview related

to bullying and gender, Cedillo has similar beliefs: “…schools are not going to talk

about sexual harassment to second graders. Because it’s not safe. It’s so much easier

to talk to them about bullying” (in Chamberlain, 2003, p. 3).

21

Reasons for Addressing Gendered Harassment in Elementary School

Gendered Harassment Affects Everyone

Poteat and Espelage (2005) state that homophobic content and bullying are

closely related and that both should be concurrently addressed. Harassment often

occurs during the school day (D’Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002; Plummer,

2001) and generally is perpetrated among groups of same age students (River et al.,

2007). The 2005 Harris Interactive and GLSEN Report, From Teasing to Torment,

reports that the second most frequent reason cited for being teased is a student’s

perceived sexual orientation. Espelage and Swearer (2008) suggest that as early as

elementary school, students internalize negativity associated with being anything but

heterosexual. Tharinger (2008) highlights the belief that homophobia is, “the last

bastion of prejudice in our society” (p. 221). Homophobic harassment affects

everyone. Epstein (2001) has determined that homophobic harassment impacts

everyone in the environment in which it occurs due to the fact that it is often used to

reinforce traditional gender roles for both males and females.

Negative Psychological and Social Consequences

Homophobic harassment has been shown to cause psychological and social

consequences for the victims (D’Augelli et al., 2002; Poteat & Espelage, 2007; Rivers,

2001). The California Safe Schools Coalition (2004) reports that victims of

homophobic harassment are less connected to school, more likely to have low grades,

are three times as likely to miss school due to feeling unsafe and to take a weapon to

school. Students also reported being twice as likely to seriously consider suicide or to

22

make a plan for suicide (California Safe Schools Coalition). Young and Sweeting’s

2004 study involving 15-year olds found that gender atypical boys had a much

stronger chance of being victimized by bullies, had fewer friends and had more

psychological problems than their gender typical male counterparts had.

The Link Between Gendered Harassment and School Violence

Multiple studies found that homophobic harassment has been related to

aggressive and violent behavior within schools (Kimmel & Mahler, 2003; Poteat &

Espelage, 2005; Rivers 2001). School violence is often misattributed to psychological

risk factors when in fact gender and school culture are more important risk factors that

have been grossly overlooked (Kimmel & Mahler; Stein, 2007). Kimmel and Mahler

state that, “They pay little or no attention that all the school shootings were committed

by boys—masculinity is the single greatest risk factor in school violence” (p. 1442).

An analysis of 23 school shootings between 1992 and 2001 revealed that almost all the

shooters were victims of bullying, violence and gay-baiting. Although none of the

shooters was identified as gay, they were ostracized because they did not fit the typical

masculine mold (Kimmel & Mahler).

Teacher Responses to Gendered Harassment

Many teachers are likely unaware of their own attitudes surrounding

homophobia. Conoley (2008) claims that, “Homophobic attitudes are among the last

utterable prejudices among adults” and by ignoring homophobic behavior teachers are

silently endorsing it (p. 219). Unfortunately, some teachers feel social pressure to

reaffirm gender stereotypes by contributing to the homophobic harassment that goes

23

on in schools. An online study reported that 88% of the students said that homophobic

comments were used at least some of the time in front of teachers or staff and many

times the teachers or staff did not intervene (Harris Interactive & GLSEN, 2005).

Although the incidence of most types of harassment diminish as people age,

homophobic harassment does not decrease as people grow older (Rivers et al., 2007).

In fact, Powlishta’s (2000) study found that adults hold children more accountable for

gendered norms than they do other adults. Although adults generally had more flexible

feelings regarding gender stereotypes, when it came to children the adults were not so

flexible, expecting boys to be masculine and girls to be feminine.

Ill-Equipped Teachers

Without the backing of a curriculum or specialized training, many teachers feel

inadequate and uncomfortable dealing with harassment related to homophobia

(Conoley, 2008; Whitman, Horn & Boyd, 2007). Given that most harassment is verbal

and most of the verbal harassment is homophobic or sexist (Harris Interactive and

GLSEN, 2005), it seems paramount that teachers have access to curriculum and

become educated to respond confidently and effectively when faced with instances of

gendered harassment.

Conclusion

The research highlighted many instances of gendered harassment that occurred

in schools. Whether the harassment was related to homophobia, gender nonconforming expression or heterosexual harassment (Meyer, 2006) the research is clear.

Gendered harassment is harmful to everyone involved (Epstein, 2001). Students who

24

are present during the harassment and students who are targeted for the harassment

both suffer negative consequences (D’Augelli et al., 2002; Poteat & Espelage, 2007;

Rivers, 2001). Psychological consequences are that students are less connected to

school, suffer academically, feel unsafe, and are more apt to consider suicide

(California Safe Schools Coalition & University of California Davis, 2004). Social

consequences are that school cultures are threatened (Kimmel & Mahler, 2003; Stein,

2007), boys and girls are unable to express their authentic selves (Orenstein, 1994;

Pollack, 1999; Sadker & Sadker, 1994) and the gender norms are maintained giving

power to males over females (Epstein, 2001; Meyer, 2006). Addressing gendered

harassment is important in elementary school (Espelage & Swearer, 2008). Teachers

need access to lessons and curriculums and need school policies and training to

support their efforts to combat gendered harassment (Conoley, 2008; Whitman et al.,

2007).

25

Chapter 3

METHODOLOGY

Setting

The project’s three lesson plans are designed for elementary schools that have

adopted the Second Step: A Violence Prevention (SSAVP) program. Specifically, the

lessons are an addendum to be used with the second grade SSAVP curriculum kit, at

Del Paso Manor Elementary School in the San Juan Unified School District,

Sacramento, California.

Participants

The project’s three lessons are designed for use with second grade students.

Del Paso Manor School is a school that serves students kindergarten through sixth

grade. It is located in a working class neighborhood within Sacramento. The ethnic

profile of the student population is 55% White, 22% Hispanic or Latino, 10% Asian,

9% African American, 2% American Indian or Alaska Native, 2% Filipino, < 1%

Pacific Islander. Thirteen percent of the students are English Language Learners. The

number of students who qualify for the free or reduced lunch program establishes the

economic school profile. To be eligible for the free lunch, the household income needs

to be $28,665, or less, annually. At Del Paso Manor, 38% of the students qualify for

the free and reduced lunch program.

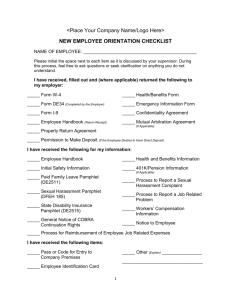

Instruments

Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum is distributed by Committee

for Children. The program has curriculum kits for students preschool age through

26

ninth grade. The program’s goals are to teach students social skills, problem solving

skills and anger management. The format of the lessons is consistent throughout the

grades. The curriculum provides the teacher with a series of lessons for each of the

program’s goals. Each lesson has a large photo-lesson card that portrays children

involved in a social situation who are the same age as the students in the classroom.

As the students look at the photo, the teacher is guided through the lesson by a script

on the back of the card. The specific kit to be used with the project’s three lessons is

the second grade SSAVP program kit.

Design

The teacher’s guide for the Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum

(SSVPC) grade two curriculum kit outlines the specific strategies used within the

program and the format for the photo-lesson cards. According to the teacher’s guide,

research has shown that best practice for teaching behavior skills is a combination of

methods such as modeling, practice, coaching and positive reinforcement (Elliot &

Gresham, 1993; Ladd & Mize, 1983). SSVPC lessons require teachers to use five

main teaching strategies. The lessons generally begin with storytelling. Storytelling is

used to set up the social situation in order to explore the appropriate strategies related

to the targeted social skill. The lesson is scripted with the bold face type indicating

suggested teacher parts. The photo-lesson card is used to help the students visualize

the social situation to be explored.

Directly following the storytelling, teachers engage the students in a guided

class discussion that contains open-ended questions. This discussion accounts for

27

about half the time needed for the lesson. Suggested answers appear in parentheses

after each question.

Following the class discussion, the lessons may include role-play. Role-play

has been deemed an effective teaching strategy because it facilitates modeling, skill

rehearsal, practice and feedback. Role-play accounts for about half the time needed to

teach the lesson. Two types of modeling opportunities are included: teacher modeling

and peer modeling. Teacher modeling is when the teacher leads or participates in a

role-play with a student. The teacher takes on the role of the lead character and acts

out the taught strategies. Peer modeling is when peers act out role-plays to practice the

social skills being taught. Peer modeling is important because the language and

situations closely mirror their own social situations making the skills learned more

applicable.

Another strategy used in SSVPC is coaching. Coaching is when teachers show

and tell students what to do. As student learning takes place, the teacher guides and

helps facilitate the learning.

The last strategies used are debriefing and reinforcement. Debriefing occurs

after the role-play. This affords the students an opportunity to hear precise feedback

that reinforces the concepts taught within the lesson. Reinforcement of the social skills

taught should also occur throughout the day as the teacher observes the students using

the preferred social skills taught.

Currently, lessons that address gender bullying are absent from the elementary

grade lessons of SSVPC. The project’s three lessons include the same format and

28

teaching strategies as SSVPC and serve as addendums for the existing curriculum for

second grade. The lessons were created and aligned with the current format of the

SSVPC curriculum because lessons that are integrated into an existing curriculum are

less of a burden on teachers and are more accessible to students (Stein, 2007). The

goals of the lessons are to teach students socially competent skills to deal with

diversity, name-calling and gender-biased comments.

Procedures

The three lessons can be taught as an additional unit for the SSAVP program.

The lessons should be taught after unit one of the SSAVP curriculum. It is left to the

discretion of the teacher to choose the exact time within the curriculum to best meet

the students’ needs. Each lesson requires 45 minutes of teaching time. The ideal

presentation is to have students seated in close proximity to the teacher. The lessons

should be taught as a series of lessons. The lessons can be taught in any order within

the series; however, it is recommended to teach Lesson One: Respecting Diversity

first, followed by Lesson Two: Name-Calling, and then Lesson Three: Gender-Biased

Comments. Lesson One is to be used with photo-lesson card number 15. Lesson Two

is to be used with photo-lesson card number four. Lesson Three is to be used with

photo-lesson card number thirteen. The lessons are scripted lessons with the teaching

strategies incorporated directly into the lessons.

29

Chapter 4

DISCUSSION

Conclusion

A review of the literature on gender bullying has highlighted key elements that

need to be incorporated into social skills lessons in order to prevent future incidences

of bullying and harassment based on gender. Respecting diversity, eliminating namecalling and responding to sexist comments were common recommendations

throughout the literature leading to the conclusion that respecting diversity should be

an overarching goal of all social curriculums. The findings related to moral

disengagement theory highlight the importance of teaching strategies so that children

develop self-regulatory, pro-social behavior that stresses the importance of selfresponsibility and the humanization of all people (Bandura et al., 1996).

Limitations

Two limitations of the project are the specific age of the target population and

the single focus on gender. My lessons are designed for early elementary age students

from six to eight years old, specifically for use in second grade as an addendum for

Second Step: A Violence Prevention Curriculum. The lessons must be implemented

using the second grade kit in order to have access to photo-lesson cards 4, 13 and 15.

Another limitation is the limited affect three lessons will have on the second

grade students. The California Safe Schools Coalition (2004) suggests that school

wide policies and training for staff for dealing with gendered harassment improves the

30

school climate. The lessons created for this project will not be utilized school wide,

nor do they include policy or training.

Cultural norms and beliefs related to gender and sexuality limit the type and

amount of information shared with the students. Due to the age of the target

population, issues related to sexuality, hetero or homosexuality will not be included.

Although the exclusion of sexuality is acceptable in the early grades, there is a great

need for education in upper elementary grades to deal with issues of harassment

surrounding sexuality and gender nonconformity. Gender norms that frame gender in

terms of either female or male limit the discussion of gender. It excludes thinking of

gender beyond the normed definitions of male and female. Discussions of gender, in

order to be inclusive of all students, needs to recognize the full spectrum of gender

identity and the way that spectrum is manifested in behavior and dress.

Recommendations

Lesson One: Respecting Diversity encourages students to explore the

similarities and differences among people. Due to the psychological and social

consequences of homophobic harassment (Poteat & Espelage, 2005; Swearer et al.

2008), it is suggested that educational programs teach respect for sexual orientation

diversity. In elementary school, teaching respect for diversity in sexual orientation can

be accomplished by increasing tolerance for varied gender expressions. Addressing the

rigidity of expectations surrounding gender can help develop a school climate that is

supportive of all children, including students who are gender nonconforming.

(Franklin, 2000; Swearer et al.). All individuals suffer the negative consequences of

31

homophobia, not just gays and lesbians (Poteat & Espelage, 2005). The objectives of

Lesson One are to identify similarities, to name the basic needs of all people, and to

discover and celebrate the differences between themselves and their peers.

Lesson Two: Name-Calling targets name-calling because research shows that

verbal harassment is the most common form of gendered harassment. Most of the

verbal harassment involves homophobic epithets and name-calling (Harris Interactive

& Gay Lesbian Straight Education Network, 2005; Rivers, 2001). Although some

perceive name-calling as inconsequential, it is anything but (Phoenix et al., 2003;

Poteat & Espelage, 2005; Swearer et al, 2008). Some victims are harassed on a daily

basis until they exit school (Conoley, 2008; Rivers et al., 2007). Students reported

long lasting negative feelings associated with having homophobic epithets targeted

towards them. Students who were verbally harassed with homophobic comments were

less connected to school, felt unsafe, and suffered psychological consequences

(California Safe Schools Coalition, 2004; Swearer et al.). Eliminating homophobia

should include disallowing permission for adults to ignore children who call other

children derogatory names such as faggot (Phoenix et al.; Plummer, 2001; Swearer et

al.). The objectives of Lesson Two are to teach students to address people by their

given names and to understand that name-calling can be extremely hurtful and is not

acceptable behavior.

Lesson Three: Responding to Gender-Biased Comments teaches that genderbiased comments limit everyone. Making assumptions and stereotypes about people

based on their gender silences their authentic selves, thus reducing their true potential

32

(Kimmel & Mahler, 2003; Phoenix et al., 2003; Swearer et al., 2008). The masculinity

codes ruling young boys’ lives are strict and confining (Pollack, 1999). The

expectation placed on girls to express the perfect balance of femininity and

masculinity (Kane, 2006) is impossible. Reinforcing the social stereotypes of gender

reinforces the traditional power structure, giving power to males over females

(Tharinger, 2008). Students should be taught strategies to combat verbal gender

bullying. A study concluded that without intervention, students almost never

confronted their peers’ gendered comments (Lamb, Bigler, Liben, & Green, 2009).

Arming students with strategies to directly address gender-biased comments is

paramount. The two objectives of Lesson Three are to enable students to recognize

gender-biased comments and to formulate and adopt phrases to use in response to the

comments.

33

APPENDIX

Lesson Plans

34

Lesson 1: Accepting Diversity

Concepts

All people have similarities, things that are the same about them, and differences,

things that are different about them. Similarities are usually easy to understand

because they are familiar to us. Differences can be hard to understand and may

seem unusual.

Language concepts: fact, judgment

Objectives

Students will be able to:

Identify things that all people need (similarities)

Identify qualities about themselves that are unique (differences)

Define the concept of “making judgments”

Story and Discussion

Today we will explore the idea that all people have similarities and

differences. We will learn how to make connections with people that appear

or look different. We will learn that making judgments about people based

on their looks can be hurtful.

Show Photo. This is a photo of a boy.

1. Is this boy nice or mean? How do you know? Is this boy smart? How do

you know? Is this boy good at sports? How do you know? Is this boy a

good reader? How do you know? Would this boy be a good friend? How

do you know?

A fact is something that can be proven, it is something known to be true. A

judgment is your opinion, or what you think or feel about someone or

something without knowing for sure. Making judgments about someone

based on what they look like can be hurtful. People often make judgments

when they do not fully understand someone. Making judgments about

people doesn’t give them a fair chance.

Look at photo again. Let’s find ways to put our judgments aside and try to get

to know this person.

35

2. What can you say or do to get to know him? (You might greet him and ask

him his name. Ask him if he likes to swing, play hopscotch, play on the

monkey bars. You might ask him if he has a brother or sister. )

Role-Play

Let’s practice getting to know someone. I am going to pretend like I am a

student and you don’t know any real facts about me. Maybe you’ve seen me

before or made judgments but you’ve never gotten to know me. I need a

volunteer to role-play how you can get to know me.

What you just did was try to find out something that is similar about me.

You were trying to find something we have in common. All people need the

same things: family, friends, a safe place to live, food to eat, water to drink.

Finding similarities can bring people together and help them make

connections.

Once connections are made, finding out about people’s differences can

make our lives richer, more full. Here you can give an example of a

similarity and a difference you share with the same friend (e.g., my friend

and I both love to play soccer together, but she loves to cook and I don’t. I

love to read and she doesn’t. We get to add to each other’s lives with our

differences. She invites me to her house and cooks great meals for me and I

read interesting books and tell her great stories.).

Think of several things you like or some things you are good at. Pair share

with the person next to you and tell them about what you like or what you

are good at. Then to listen to him/her share. When you are done, we will

record information on the white board about people in our class. We’ll look

at our similarities and differences.

Wrap-Up

Today we learned that all people have similarities and differences. All

people need similar things: family, friends, a safe place to live, food and

water. Differences can make our lives more interesting. We learned that

both similarities and differences are important in our lives. Making

judgments based on what people look can be hurtful to people. It is worth

taking the time to get to know a person to find out the facts about him/her.

36

Lesson 2: Name-Calling

Concept

Everybody has a special name. Everybody deserves to be respectfully called by

his or her name.

Objectives

Students will be able to:

Understand that everyone has a name.

Understand that it is respectful to address people by their names.

Understand that name-calling can be extremely hurtful and should not be

done.

Story and Discussion

Today we will learn that everybody has a special name.

Show photo. This is Donny. Donny wanted Jamal to play in his fort

but Jamal didn’t want to. Jamal wanted to read instead. Donny

just called his friend Jamal a “sissy”.

1. How do you think Jamal feels? (Hurt, disappointment.)

How can you tell? (He has a frown, his head is down turned.)

Name-calling is extremely hurtful. People do not easily forget when

someone calls them a hurtful name. Calling someone a name is as hurtful as

hitting or pushing someone. Name-calling is like hitting or pushing

someone’s feelings. Name-calling is NEVER okay.

2. Why do you think Donny called Jamal a hurtful name? (He was upset that

Jamal didn’t want to play in the fort. He thinks playing in a fort is better than

reading.)

3. Do you think Donny solved the problem by calling Jamal a name? (No, it

just made the problem worse.)

Everybody has a special name and that is the name that should be used

when addressing the person. People’s personal names are important to

them and to their families. A simple sign of respect is to call people by their

given names. Some people have nicknames given to them by close family or

friends. Before you call a person by his/her nickname it is courteous to ask

37

permission. Respect the person’s answer. Sometimes people are

comfortable with only certain people calling them by their nickname.

4. What do you think Donny could have done instead of calling Jamal a

name? (He could have told Jamal he was disappointed because he really

wanted to play in the fort together. He could have asked Jamal to play in the

fort for a while and then they could read together later. He could have asked

Jamal if there was something else they could do together besides read.)

5. What could Jamal do after the name-calling incident? (He could have

responded, “My name is Jamal. Calling me other names is not okay” or,

“Calling me names doesn’t solve the problem.”)

Name-calling can be hurtful if it only happens once but it can

become a serious problem when it happens over and over again.

Reporting repeated name-calling to a trusted adult can help both

you and the other person.

Activity

Tell students what you know about your given name. Tell details such as where

your name comes from and why your name is special to you and your family.

Have students pair share what they know about their own special names. Once

students have shared; offer time for students to share aloud their stories.

Wrap-Up

Today we learned that all people have special names given to them. Part of

showing people respect is by calling them their given name. Name-calling is

NEVER okay. Reporting repeated name-calling to a trusted adult can help

everyone.

38

Lesson 3: Responding to Gender-Biased Comments

Concepts

People have the right to choose their own likes and dislikes.

People have the right to express their own feelings.

Language concept: gender, rights

Objectives

Students will be able to:

Identify a gender-biased comment.

Respond appropriately to a gender-biased comment.

Story and Discussion

Today we will learn about gender-biased comments. Gender is if you are a

girl or a boy. A gender-biased comment is a comment that tells you

something about being a boy or a girl. Comments about girls and boys can

be limiting because they are not always true for all boys or all girls. For

example: Girls like dolls and boys like trucks are gender-biased comments

because not all girls like dolls and not all boys like trucks. In fact, some boys

like dolls and some girls like trucks.

Show Photo. This is Lauren. She wants to play football with Zach. When

Lauren asks Zach if she can play, he says, “Girls don’t play football, only

boys do.”

1. How do you think Lauren feels? (She feels hurt, maybe mad about being a

girl.)

2. Why do you think Zach said, “Girls don’t play football, only boys do.”

(Maybe he only sees boys or men playing football. Maybe someone told him

football is a boy’s game.)

Telling people what they can or cannot do, or can and cannot feel because of

their gender is wrong. People have the right to choose activities they like

and have the right to feel the way they feel. A right is having the freedom to

be able to do things, to be able to share your own ideas, and to be able to

have your own feelings about things. All people have the right to choose

their own activities, share their own ideas, and have their own feelings. It

doesn’t matter if you are a girl or a boy. All people have equal rights. There

39

is no such thing as boy things, or games, or colors, or toys or feelings, just

like there is no such thing as girl things, or games, or colors, or toys, or

feelings.

3. What do you think Lauren can say to Zach? (She can say, “There is no such

thing as boy games or girl games. People have the right to choose their own

games.” She can tell Zach that girls can play football too. She can say, “Well,

I’m a girl and I like to play football.”)

Role-Play

Sometimes people know something is wrong, but they don’t know how to

stand up for their rights. I am going to role-play that I am a child. I will

make a comment. You pretend that I am talking to you. Raise your hand if

you have a response to my comment. We can brainstorm a list of responses

to gender-biased comments for you to use to stand up for your rights.

Select comments from the list below. Modify the comments as needed or adapt

the comments to reflect the experiences of your students.

“You can’t pick pink, you’re a boy.”

“Only girls can play this game” or “Only boys can play this game”

“Be tough, act like a man”

“Girls are better at coloring”

“I can run faster than you because I’m a boy”

“Girls are better than boys” or “Boys are better than girls”

Write down student responses. After the role-play, go over the response list with

students and work together to formulate several simple, quick catch phrases to

use in response to gender-biased comments. (Examples: “It doesn’t matter if

you’re a girl or a boy, we all have equal rights.” “Colors, games, activities, feelings

are for everyone, not just boys or not just girls.” “That’s not fair, everyone has the

right!”)

Wrap-Up

Today we learned about gender-biased comments. By using the phrases we

made today, you can stick up for your rights and the rights of your

classmates.

40

Transfer of Learning

Post the class generated catch phrases where students can see them and use

them. Refer to the phrases as needed.

41

REFERENCES

Alameda Unified School District. (n.d.). Retrieved March 27, 2010, from

http://www.alameda.k12.ca.us/index.php/home/caring-schools-communitycurriculum

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of

moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 71, 364-374.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss. New York: Basics Books.

Brown, L. M., Chesney-Lind, M., & Stein, N. (2007, December). Patriarchy matters:

Toward a gendered theory of teen violence and victimization. Violence Against

Women, 13, 1249-1273. Retrieved December 1, 2009, from

http://vaw.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/13/12/1249

California Safe Schools Coalition and University of California, Davis, 4-H Center for

Youth Development. (2004). Consequences of harassment based on actual or

perceived sexual orientation and gender non-conformity and steps for making

schools safer. Davis, CA: Author.

Chamberlain, S. P. (2003). An interview with…Susan Limber and Sylvia Cedillo:

Responding to bullying. Intervention in School and Clinic, 38, 236-242.

Cherlin, A. J. (1996). Public and private families: An introduction. New York:

McGraw-Hill.

42

Committee for Children. (2002). Second step: A violence prevention curriculum,

Grades 1 – 3, Teacher’s guide for the grade 2 curriculum kit. Seattle,

WA: Author.

Conoley, J. C. (2008). Sticks and stones can break my bones and words can really hurt

me. School Psychology Review, 37, 217-220.

D’Augelli, A. R., Pilkington, N. W., & Hershberger, S. L. (2002). Incidence and

mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and

bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 148-167.

De Beauvoir, S. (1952). The second sex. (H. M. Parshley, Trans.). New York: Vintage

Books.

Duncan, N. (2006). Girls’ violence and aggression against other girls: Femininity and

bullying in UK schools. In F. Leach & C. Mitchell (Eds.), Combating gender

violence in and around schools (pp. 51-59). Sterling, VA: Trentham Books.

Elliot S. N., & Gresham, F. M. (1993). Social skills interventions for children.

Behavior Modification, 17, 287-313.

Epstein, D. (2001). Boyz’ own stories: Masculinities and sexualities in schools. In W.

Martino & B. Meyenn (Eds.), What about the boys: Issues of masculinities in

schools (p. 106). Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2008). Addressing research gaps in the intersection

between homophobia and bullying. School Psychology Review, 37, 155-159.

43

Franklin, K. (2000). Antigay behaviors among young adults: Prevalence, patterns, and

motivators in a noncriminal population. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15,

339-362. Retrieved December 1, 2009, from

http://jiv.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/15/4/339

Gender Equity Resource Center. (2010). LGBT Resources: Definition of terms.

Berkeley, CA: University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved April 17, 2010,

from http://geneq.berkeley.edu/lgbt_resources_definiton_of_terms

Harris Interactive and Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network. (2005). From

teasing to torment: School climate in America, a survey of students and

teachers. New York: GLSEN.

Harris Interactive for American Association of University Women Educational

Foundation. (2001). Washington, DC: American Association of University

Women Educational Foundation.

Harris, J. (1995, July). Where is the child’s environment? A group socialization theory

of development. Psychological Review, 102, 458-489.

Jacklin, C. N., & Maccoby, E .E. (1978, September). Social behavior at 33 months in

same-sex and mixed-sex dyads. Child Development, 49, 557-569.

Kandel, D. B. (1978, September). Homophily, selection, and socialization in

adolescent friendships. The American Journal of Sociology, 84, 427-436.

Kane, E. W. (2006). “No way my boys are going to be like that!” Parents’ responses to

children’s gender nonconformity. Gender & Society, 20, 149-176.

44

Kimmel, M. S. (1994). Masculinity as homophobia. In H. Brod, & M. Kaufman

(Eds.), Theorizing Masculinities (pp. 119-141). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications.

Kimmel, M. S., & Mahler, M. (2003, June). Adolescent masculinity, homophobia,

and violence: Random school shootings, 1982-2001. The American

Behavioral Scientist, 46, 1439-1458.

Ladd, G. W., & Mize, J. (1983). A cognitive social learning model of social-skill

training. Psychological Review, 90, 127-157.

Lamb, L. M., Bigler, R. S., Liben, L. S., & Green, V. A. (2009). Teaching children to

confront peers’ sexist remarks: Implications for theories of gender

development and educational practice. Sex Roles, 61, 361-382.

Lazarsfeld, P. F., & Merton, R. K. (1954). Friendship as social process: A substantive

and methodological analysis. In M. Berger, T. Abel, & C. H. Page (Eds.),

Freedom and control in modern society (pp. 18-66). New York: D. Van