Public Educator Retirement in Three Crucial States

advertisement

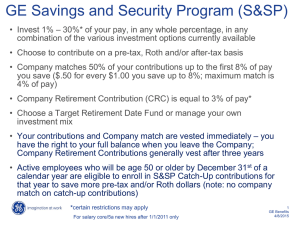

Broken Promises or Justifiable Restructuring: Public Educator Retirement in Three Crucial States Brett A. Geier, Ed.D. Assistant Professor University of South Florida Tampa, FL 33620 Dennis McCrumb, Ed.D. Assistant Professor Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, MI 49008 bgeier@usf.edu dennis.mcrumb@wmich.edu Paper Presented for the Association of Educational Finance and Policy Conference San Antonio, Texas March 14, 2014 Introduction Teacher pensions have long been considered a main attraction for an individual to enter a career in education. While teacher salaries remain below the mean compared with professionals that have comparable degrees, the benefit package offered to educators is typically an added incentive to enter the discipline. Benefit packages in public education, which are part of compensation programs, consist of retirement benefits and health insurance. Retirement benefits are a construct of the individual state government as providing a public education is a state responsibility; thus compensation for public school employees is under state jurisdiction. As will be described, most of these public retirement programs are costly and the expenditures continue to grow. Public employee pension programs require states to annually allocate hundreds of millions of dollars for the individual payouts, which are often more generous than those provided by privatesector retirement plans. 1 A schism has formed among legislators, educators, and the greater public in general between those that favor defined benefit plans (DB) and those endorsing defined contribution plans (DC). The dispute developed between those pontificating that the traditional retirement program for public school employees is unaffordable to the state, creating a financial burden on local school districts and requires reform. Those supporting the traditional defined benefit program espouse state constitutional guarantees and nefarious motives by conservative groups, which are attacking public education. The retirement system in each state has become a source of contention between those that favor the status quo and those that seek reform. For a plethora of reasons to be 1 Lafferty, Michael B., Chester E Finn, Jr., Janie Scull and Amber M. Winkler. Halting a Runaway Train: Reforming Teacher Pension for the 21st Century (Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Inst., October 2011), 4. 2 discussed, states are now reaching a point of critical mass in terms of what they can afford and are politically willing to continue or change. The cost of retirement programs is rising at a significant rate, which is putting enormous strains on state budgets, local school districts, and the taxpayers. Because state budgets are a political entity, the funding of educator retirement benefits has a polarizing effect. The Pew Center on the States declared that an unprecedented number of reforms have been enacted by states throughout the nation,2 demonstrating the national consciousness to the fact that some state systems are becoming insolvent. Other states may, indeed, have more political motives driving the change. For some states, their respective public educator pension system is quite healthy, yet some vociferously advocate change. Characteristically, in these states, conservative factions attempting to reduce public educator retirement benefits so they are more consistent with private retirement programs articulate vitriolic rhetoric. Various adjustments to retirement policy have the potential effect of reducing members’ benefits at retirement age, the amount the employee has to contribute to his or her retirement, and the age at which he or she is eligible for full benefits. Table 1 is a summary of each individual state’s public educator retirement funds in FY2010 including the total liability, percent funded, what the annual contribution from the legislature should be, and the percent the state legislature is funding the system. The table is organized from the states that have the best percent funded liability to the worst. 2 The Pew Center on the States, The Widening Gap: The Great Recession’s Impact on State Pension and Retiree Healthcare Costs (Washington, D. C.: Pew Research Center, April 2011) http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org (accessed September 12, 2013). 3 Table 1. Condition of Pension Funding for State Public Educator Retirement. Source: Pew Center on the States. The Widening Gap: Interactive. (June 8, 2012). 4 Defined Benefit Plans – The Promise Prudency dictates that individuals plan appropriately for their retirement, but if the terms of retirement programs are modified periodically after obligations have been established, it can result in massive anxiety for the employee, and potentially reduce the attractiveness of public education and ultimately cause exceptional talent to choose other career paths. The type of retirement system in public education that has been, historically, the most widely employed is termed a defined benefit (DB) program. A defined benefit plan ensures an employee a pre-determined retirement benefit based on a formula created by the state. The algorithm is typically constructed thusly: Annual Benefit = m YOS FAS3 Where m is the multiplier, YOS is the years of retirement service credit, and FAS is the final average salary. Some states require an individual attain a certain age as a qualifier to receive the full benefit package. In other cases, the multiplier is reduced if an employee elects to retire before meeting the minimum threshold. This formula yields a monetary benefit that the employee is guaranteed per annum once retired, thus the term, defined benefit. The defined benefit plans had great wealth after World War II.4 However, in a few decades, many defined benefit plans began to outpace revenue inputs. The retirement benefit paid to an employee is a sizeable portion of the total compensation, thus it can be a strong attraction for those entering the profession.5 Those individuals and organizations opposed to modifications to the defined benefit plan employ the argument that pension 3 Costrell, Robert, M. and Michael Podgursky. “Distribution of Benefits in Teacher Retirement Systems and Their Implication for Mobility,” Journal of Education Finance and Policy. 5 (Fall 2010): 524. 4 Lafferty, Halting a Runaway, 10. 5 Toutkoushian, Robert K., Justin M. Bathon and Martha M. McCarthy, “A National Study of the Net Benefits of State Pension Plans for Educators,” Journal of Education Finance 37 (Summer 2011): 25. 5 benefits are a primary reason that the individual chooses a public job.6 In addition, many of the proponents of the defined benefit program clamor that states have “promised” this program as developed; rationalizing that there is a constitutional obligation to maintain it. Supporters contend that modifications should not be made to the defined benefit program, as it is an inherent attraction to a career field that arguably does not compensate appropriately for the level of education as compared to the private sector. Defined benefit plans require states to develop retirement systems that constitutionally guarantee a pre-retirement defined benefit. In more simple nomenclature, states have made a retirement promise, and there are those that subscribe to the notion that it is unconstitutional to adjust the program, and various organizations, primarily teacher unions, have sought fit to challenge the changes in the courts. Amplifying the intricacies involved with public educator retirement plans is the fact that 31 states in the nation have 93 constitutional provisions securing benefits. 7 Simply examining the number of state constitutional articles associated with retirement benefits provides a significant indication that a defined benefit retirement has been intimately associated with state constitutions, statutes, and collective bargaining agreements. The previous statement is a notion that is no longer universally accepted. The majority of those that posit this theory are those that are direct recipients or future recipients of the benefit. Definedbenefit plans require the state to create funds that are financially supported with a combination of state dollars, employee contributions, and stock market investments. State-created defined benefit plans are not required to contain funds for individuals 6 Hess, Frederick, M. and Juliet P. Squire, “The False Promise of Public Pensions,” Policy Review 158 (December 2009/January 2010) http://www.hoover.org/publications/policyreview/72861002.html (accessed November 3, 2013). 7 Ibid. 6 currently working in the system. Defined benefit plans, therefore, have a gap between funds they currently hold and funds they will need to pay the benefit in the future. This gap is defined as the accrued unfunded liability. Liabilities are calculated based upon the amount of revenue the state allocates for the program, the amount generated by current employees of the system, and the yield on the financial investment. With all defined benefit plans, investors allocate dollars from the pension plans with the desire of meeting the plan’s promise or exceeding it. Past standards have declared that states plan for an 8% return on the investment made for pension growth. The Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) opines a reevaluation of the expected return rate due to the significant downturn in the market structure since 2008. During the years 1984 through 2009, the median investment return rate was 9.3%. Between 1990 and 2009 the median investment return rate was 8.1%. Shockingly, the median return rate plummeted to 3.9% between the years of 2000 to 2009. It is quite apparent that the “bullish” 1990s have been offset by what has been termed, “The Great Recession,” circa 2006 to the present. The target rate that was once exceeded yielded defined benefit plans that are no longer able to support the expectation. If states elect to lower their investment return assumptions, then its liabilities increase and the need for annual contributions must increase in order to fulfill the state’s obligation. This requires states to contribute more funds, and potentially put the employees at greater risk for increased investment as mandated by a state’s legislature. Due to the significance of the recession over the past four to five years, and its impact on market returns, investment experts are conceding that the once sought-after 8% return rate is now too aggressive to be employed as the standard on which to base pension 7 investment return rates. One issue identified by the Pew Center in 2011 is that with an adjusted expectation on investment rate return, the liability gap increases, which requires an annual increase in contributions either by the state and/or the individual employee. One suggestion to rectify this conundrum is to seek an alternative percent on investments that is more realistic for the financial uncertainty. Some experts suggest using more of a “riskless rate” that is analogous to a thirty-year Treasury Bond, which has ranged between 2.51% and 4.45%. The Financial Accounting Standards Board requires private sector employers that provide define benefit retirement packages to set their investment return rate at 5.22% - the rate of corporate bonds. These alternatives are credible adjustments that reflect realistic projections. The problem is that the rate change does very little to address a system that is requiring additional revenue at an alarming rate to minimize the liability. The return rate combined with other sources of revenue such as employee contribution and taxpayer contributions seek to fund the plan at an 80% level. Solvency of the program is attained when the liabilities are 80% met, which is the standard established by the General Accounting Office. In 2000, more than half of the states were 100% funded, However, in 2010, only one state, Wisconsin, was funded at this mark. In 2010, 16 states were identified as having liabilities funded at or above the 80% mark. In contrast to that statistic, 9 states were at or below 60% and two states (Illinois and Rhode Island) were funded below 50%. While some state retirement programs have been able to maintain the 80% advised threshold, the trend among states is to decrease the funding for these plans, which has increased the liability. Looking across the nation, these funds are 8 simply not going to be able to invest their way out of the conundrum they are currently experiencing.8 States are losing ground in their effort to cover the long-term liability of these pensions programs. Since the “Great Recession,” the lack of funding for these state programs has been exacerbated. In fiscal year 2010, the gap between states’ assets and their liabilities was $1.38 trillion dollars. This total included $757 billion for pension obligations and $627 billion for retiree health care. 9 The total gap represents a 9% increase over the previous year. For most states, they are positioned to cover employee retirement benefits in the short term, but it is the long-term debt that needs to be secured. Defined Contribution Plans – The Answer? There are a variety of additional proposals for reforming defined benefit programs. The concern for many is that these reforms modify pensions systems in place or significantly reduce longstanding benefits. The philosophical dichotomy is extremely polarized and simple-minded.10 One of the more crucial changes has been for states to enact a defined contribution plan or a hybrid plan. As introduced earlier, the largest difference between defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans is whether the employee or the employer handles the majority of the responsibility for the financial liability. Defined contributions provide a certain benefit to be invested and controlled by 8 Eisele-Dyrli, Kurt, “Will Pensions Bankrupt Your District?: State Retirement Funds are in Crisis, and School Systems Will Likely Pay More of the Bill,” District Administration, January 2010 http://www.districtadministration.com/article/will-pensions-bankrupt-your-district (accessed October 27, 2013). 9 The Pew Center on the States, The Widening Gap (Washington, D. C.: Pew Research Center, June 2012) 1. 10 Cavanaugh, Sean, “Personnel Costs Prove Tough to Contain,” Education Week, January 5, 2011 http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2011/01/13/16personnel.h30.html?utm_source=fb&utm_medium=rss& utm_campaign=mrss (accessed February 8, 2014). 9 the employee, which produces the conclusion the state is seeking to relinquish itself of a future liability. Many states have engaged in modifications that remove the guarantee that the state or local school district will pay the entire amount for retirement costs. For example, prior to fiscal year 2010, Michigan required the local public school to pay for employee retirement benefits, which was a percentage of the employee’s salary. This percentage was determined by the Michigan Public School Educators Retirement System and approved by the legislature. Therefore, the school district had no recourse but to pay this amount. One approach that many states have enacted is to require the individual employee to pay a percentage of his or her salary to the retirement system. Those states that have engaged in this approach have had a varied scale to the percentage utilized. Financial considerations and political posturing have been the most significant reasons for implementing the employer contribution to the retirement system. Public school employees have not willingly accepted these modifications. Publicsector unions, especially those that represent educators have been quite vociferous regarding these modifications. Obviously, the position of teacher unions is to secure the maximum amount of compensation for its membership as possible. Somewhat forecasting the future, the National Education Association (2004) published a primer for collective bargaining that amplified the position that state constitutions provided secure pension benefits in perpetuity. Much to the chagrin of state and national unions, the future did not provide the benefit protection they thought they were entitled to receive. As state legislatures began to enact requirements for employees to begin paying part of their pension, public employees, especially teacher unions, sought to contest these 10 actions in court. For example, a contentious battle raged in Florida from the summer of 2011 until January 2013 when the State Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of requiring employees to pay 3% toward their own retirement costs. State courts are finding that the legislature has the authority to make adjustments to the law, which affects various components of collective bargaining. Since it was found that the legislature has the authority to modify law dealing with collective bargaining, the position that opponents had indicating this was a subject of collective bargaining and is moot.11 It appears that employee contributions will continue for many years to come. One issue that has added to the problem is that some states failed to make the necessary contributions when their economies were healthy. According to the Pew Center (2012), state government should have allocated $124 billion in fiscal year 2010. Policymakers were only allocated 78% of the recommended amount and only 34% of what the actuaries estimated for retiree health care.12 Illinois Teacher Retirement System (TRS) The State of Illinois Teacher Retirement System is the largest pension system out of the State’s five retirement funds and has the dubious distinction of having the worst funded pension liability in the Nation. In FY2012, the state had a total retirement liability of $182.7 billion and in FY2013 faced a $55.73 billion dollar gap in the Teacher Retirement System, up from $52.08 billion. The increase in the unfunded liability is especially disconcerting as the fund actually had a 12.8% return on investments, which is more than the estimate for an annual return on investments. With this fiscal liability, the state is forced to reform its retirement system or risk default. Illinois leads the nation with 11 12 Scott et al. v. Williams et al.,107 So. 3d 379 (2013). The Pew Center on the States, The Widening Gap, 3 11 $96.8 billion pension debt and lawmakers cannot seem to agree on what changes should be made. Due to the current plan, compounding interest at 3% per year, the price of each retirees pension doubles after 20 years which is only leading to increasing debt. Recommendations have required all school districts pay their own employee pension cost instead of the state carrying the burden. There have been discussions of stopping the annual cost-of-living increase for three or more years. Although, state law requires all five systems to be 90% funded by 2045, the Illinois Auditor General suggests lawmakers fully fund two of the state’s five pension systems including the Teachers Retirement System (TRS) within the next thirty years. The state is going to have to make drastic changes to its current system and undergo a major pension reform to stabilize the pension debt and start funding the system. Teachers Retirement in Illinois – Tier I and Tier II The retirement system for public school teachers in Illinois contains two programs denoted as “Tier I” and “Tier II,” which public educators may select. The Tier I program has been in place longer than the Tier II program, yet Tier I underwent significant restructuring leading to the signing of Senate Bill 1 by Governor Pat Quinn on December 5, 2013. Tier II was created by the state in 2010. As a thorough description of Tier I is to follow, it is worth noting that various organizations are challenging the constitutionality of Senate Bill 1. Therefore, as the courts adjudicate this contest, parts or all of the revision may be moot. The benefit calculation for Tier I members is modeled after the algorithm highlighted previously in the introduction of this thesis. In Illinois nomenclature, the formula is titled the “2.2 Formula.” The formula is defined as: 12 Annual Benefit = m(2.2%) YOS FAS Where YOS is the years of service in the TRS and FAS is the final average salary. Retirement age eligibility is set according to a sliding scale. A member may retire at following ages and receive full benefits: 55 with 35 years in TRS13 60 with 10 years in TRS 62 with 5 years in TRS For Tier I members, the final average salary is the member’s highest average salary earned during 4 consecutive years out of the last 10 years of service. The maximum benefit is capped at 75% of the member’s salary with a salary cap of $110,631. The salary cap rises annually at one-half of the annual rate of inflation in the previous year. TRS members’ contribution will actually decrease from 9.4% to 8.4% under the new legislation. The cost of living adjustment (COLA) in Senate Bill 1 includes two processes by which calculations are based: New COLA Formula and Rates for Tier I Active and Retired Members and COLA Calculation for Retired Tier I Members Awaiting Their First COLAs. COLA for Active and Retired Members 1. Each member, upon retirement, will multiply his/her total service credit by a factor that is initially set at $1,000. The pension threshold will be used in the future to determine the annual COLA; 2. Beginning in 2016 and in every year thereafter, the $1,000 threshold multiplier will be increased by the rate of inflation, but the rate will not fall below 0% in case inflation is negative; 13 A member may retire at age 55 if he or she has at least 20 years of service with TRS. However, the benefit will be reduced by 6% for every year the member is under age 60. 13 3. As long as a member’s pension is less than his or her current pension threshold, when a member is eligible for a COLA it will be 3% compounded; 4. Once a member’s pension equals or exceeds his or her threshold, the COLA calculation changes. The COLA in every year then becomes 3% of the member’s current threshold amount.14 COLA Calculation for Retire Tier I Members Awaiting First COLAs 1. Under state law, a Tier I member who retires after attaining the age of 55 but before turning age 61 will accumulate an annual COLA, but he or she will not collect those accumulated COLAs until the January after he or she turns 21; 2. Under the old pension law, the COLA that accumulated for these members was 3% compounded; 3. If the law is implemented at a time when a member is still accumulating COLAs but has not yet received any of those COLAs, and the member’s pension exceeds their current pension threshold, the calculation for the accumulated COLAs will be a combination of the old law’s 3% compounded increase and the new law’s increase, which is the current pension threshold multiplied by 3%.15 The service credit that will be used in calculating the new pension threshold will equal all of the service credit that TRS used or will use to calculate the initial pension. This eligible service credit includes all regular service; any service time purchased by the member under an early retirement incentive; any optional service purchased by the member, such as leaves of absence, substitute teaching and teaching service in another state; and, for anyone who is a TRS member prior to June 1, 2014, unused sick time. Tier II members are able to elect this track if he or she was employed after January 1, 2011. Senate Bill 1 increases the minimum age to 67 with 10 years of TRS service credit. The cap on salary is 75% of the annual average salary and no salary will 14 Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois, New Pension Benefit Law for TRS (January 31, 2014) http://trs.illinois.gov/press/reform/sb1.htm (accessed February 10, 2014). 15 Ibid. 14 exceed a limit that increases more slowly than the consumer price index (CPI). The current limit is $110,631. While the same “2.2 Formula” is employed for Tier II as Tier I, the only difference is with the final average salary. For Tier II members, the highest salary average is based upon 8 consecutive years out of the last 10. Social Security Social Security has never been included in Illinois teachers’ retirement. If you paid into Social Security through other employment, your Social Security benefits are reduced if you receive a TRS pension. If teachers were to pay into Social Security, the local school district would have to pay an additional tax to Social Security, which would increase costs to taxpayers. Teachers' retirement benefits through TRS were significantly better than those offered under Social Security. Since teachers do not pay into Social Security, they are penalized if they draw the benefits from previous employment. Retired State Employees to Pay Health Insurance Premiums On June 12th, 2013, Governor Quinn signed legislation that requires all future and current retired employees to pay health insurance premiums. The new law is PA 97-0695. The majority of retired TRS members already pay health insurance premiums. The law sets up a sliding scale in which members will pay premiums based on retirement income and years of service. Under the old law, state employees with twenty years of service did not pay premiums for health insurance through retirement. Depending on the outcome of the pension reform, health insurance could be used as a bargaining tool and a way to help the state cutback on debt. 15 Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System Michigan recently enacted legislation in 2012 to help eliminate a problem with the Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System (MPSERS). The problem is an increasing unfunded accrued liability. In FY2013, the accrued actuarial unfunded liability soared to $62.7 billion combined with the actuarial value of assets of $38.4 billion for a fund ratio of 61.3%. 16 The funded ratio amplifies a downward trend, as Michigan maintained a public educator retirement system that was 72% funded in FY2010. The ability to maintain a solvent retirement system for Michigan’s public school teachers is becoming more disparaging. Illumination of the conundrum is required in order preserve a benefit for all public school employees in a manner that is equitable for employees as well as maintaining all public sector services. A historical analysis is pertinent prior to addressing solutions and identifying conflicts between members of the retirement system and those charged with funding it. The legislature adopted the Michigan Public School Employees Retirement Act (MPSERS) in 1945. This Act was originally designed to provide pension benefits, excluding health care, for retired school employees. 17 MPSERS became mandated as part of the Michigan State Constitution of 1963. 18 The health care benefits are not constitutionally guaranteed, but rather an act of legislation enacted in 1975.19 However, these healthcare costs were not funded. Costs for MPSERS pension benefits have been 16 Financial Services For Office Of Retirement Services, Michigan Public School Employees Retirement Services: Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2013 (Lansing, MI: MPSERS, September 2013): 8. 17 Tom Gantert, “Public School Pension System Totally Broken: Taxpayers on the Hook for Billions in Unfunded Liabilities,” CAPCON: Michigan Capitol Confidential, June 24, 2013, http://www.michigancapitolconfidential.com/18797 (accessed on February 3, 2014). 18 Michigan Constitution, art. 9, sec. 24. 19 Michigan Legislature, The Public Schools Employees’ Retirement Act, PA 244 (Lansing, MI, 1975), repealed by PA 300 of 1980. 16 fully funded by the State from its inception until 1974. At that time, the State required all local school districts to bear partial costs of the program at the rate of 5% of salary for all public school employees. Substantial change occurred with the voter-approved Proposal A, placing more responsibility for the retirement program on the local school district. The per pupil foundation allowance increased dramatically for most districts in 1995, however, local districts are now required to pay the entire amount requested by MPSERS, which was established at 14.56% that first year. This change transferred future obligations and a significant portion of the solvency of the system to Michigan school districts.20 As delineated in Table 2, the rate districts must pay has significantly increased and has created an excessive financial burden for all districts. Also, employer rates have changed as the pension plans have changed, most recently amplified in the past few years with the passage of detailed legislation requiring significant reform of MPSERS. 20 MPSERS, Major Changes in Recent Years and More to Come (Lansing, MI: MPSERS, 2012) www.pscinc.com (accessed January 13, 2014). 17 Table 2. MPSERS Percentage Cost to Local School District Source: Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System (January 2014). In 2013-14 the State of Michigan capped the employer contribution rate at 24.79% and contributed the additional 4.56% stabilization rate needed to financially stabilize the Michigan School Employees Retirement System. 21 In future years, the local school district’s contribution rates will be capped, and the State will provide the additional financial support as needed. The financial burden placed on districts was a result of MPSERS having an unfunded accrued liability of $60 billion in 2012 even though the system has assets of $45 billion.22 There are many reasons causing this unfunded liability, including generous pension plans, offering early retirement incentives, increase in the number of charter 21 Office of Retirement Services, Michigan Public School Employees Retirement Service, http://www.michigan.gov/orsschools (accessed February 19, 2014). 22 Nancy Derringer, “Teacher Retirement Fund Has $45 Billion Hole,” Bridge Magazine, April 24, 2012. http://bridgemi.com/2012/04/teacher-retirement-fund-has-45-billion-hole/ (accessed January 13, 2014). 18 schools, fewer workers per retiree and rising medical costs. Guarantees were made to MPSERS members, but many of those promises have been broken in an effort to overcome the unfunded accrued liability problem. 23 The MPSERS benefit plans have changed over the years with the majority of the changes taking place over the past four years. Currently, there are multiple plans in effect: the Basic Plan, Member Investment Plans (MIP) (Fixed, Graded, & Plus), and Pension Plus (Hybrid) Plan. A summary of each plan is provided below. The Basic Plan This is a defined benefit program that includes employees hired prior to January 1, 1990, who chose not to opt into the MIP plan when it was introduced in 1987. The pension formula for the basic plan is defined thusly: Annual benefit = m(1.5%) YOS FAS Where YOS is the years of service and FAS is the final yearly salary average. For the basic plan a retiree calculates final yearly salary average as the average of the five highest consecutive years of service. A member is vested after 10 years and may retire at age 55 with 30 years of service or age 60 with 10 years of service. The Basic Plan is a noncontributory plan whereby employees do not contribute toward their retirement. Members are allowed to buy service credit on certain criterion. This plan pays 100% of the medical benefits for the retiree and 90% for dependents. It also pays 90% of vision and dental premiums for both the member and his or her dependents. The Basic Plan does not offer any cost of living adjustments. 23 Ibid. 19 The Member Investment Plan This defined benefit plan was implemented January 1, 1987 and members could choose the basic plan or change to the new Member Investment Plan (MIP) plan. This plan enhanced the benefits for retirees, but required a percentage salary contribution from employees towards their pension. Employees hired after January 1, 1990 no longer had the option to join the basic plan, but were automatically enrolled in the MIP plan. With the increased benefits from this plan, the unfunded accrued liability began to grow. The plan’s formula and characteristics for benefits are: Annual benefit = m(1.5%) YOS FAC Where YOS is the years of service and FAC is the final average yearly salary. The FAC defined as the average of the 3 highest consecutive salary years. Members are eligible to retire if he or she is age 46 with 30 years of service or age 60 with 10 years of service. MIP members become vested in this program after 10 years of service. Service credit is possible to purchase under certain criterion. The MIP program has employee contributions that for some categories are graduated based upon salary. The following are the MIP categories and the required employee contribution: MIP Fixed A member in the MIP Fixed program either elected MIP before January 1, 1990 or was a Basic Plan member who enrolled in the MIP by January 1, 1993. The member is required to contribute 3.9% of pretax salary. 20 MIP Graded If a member worked between January 1, 1990 and June 30, 2008 or is returning member who did not work between January 1, 1987 and December 31, 1989, the member contributions are based on Table 3. Table 3. MIP Graded Contributions Source: Michigan Public School Employees Retirement Service. MIP Plus MIP Plus members worked between July 1, 2008 and June 30, 2010. These members are required to pay the contributions in Table 4 in pretax salary. 21 Table 4. MIP Plus Contributions Source: Michigan Public School Employees Retirement Service. The MIP plan provides for a cost of living adjustment of 3% non-compounding. In addition, for this plan, MPSERS will pay 100% of medical benefits for the retiree, 90% for dependents and 90% for dental and vision benefits for the retiree and dependents. MPSERS pays a graduated premium towards health insurance for those hired after July 1, 2008 under the following criteria: requires 10 years of service to vest in health benefits, provides 30% of the premium beginning with 10 years and adds and addition 4% fore each year after 10 with a cap of 90% with 25 years of service. The Pension Plus Plan The Pension Plus Plan is for those members employed after July 1, 2010 and is a hybrid of the defined benefit and defined contribution plan. In a defined benefit plan the recipient receives a fixed monthly benefit upon retirement. The legislature has been considering for many years the need to turn the various pension programs into a complete defined contribution system to limit the State’s financial liability. However, the cost to the State of maintaining the payout of current retirees in concert with the cost of future retirees was insurmountable. The calculus and characteristics for the benefit is as follows: 22 Annual benefit = m(1.5%) YOS FAC Where FAC is the final average yearly compensation and YOS is the years of service. FAC is defined as the average of the 5 highest consecutive years of salary. Members may retire with 30 years of service at age 60 and are vested after 10 years. Members of this plan pay the same contributions as MIP Plus as shown in Table 4. A member may not purchase service credit and there are no cost of living adjustments. MPSERS pays a grade premium towards health insurance for those hired after July 1, 2008 under the following criteria: requires 10 years of service to vest in health benefits, provides 30% of the premium beginning with 10 years and adds an additional 4% for each year after 10 with a cap of 90% with 24 years of service. The Pension Plus Plan is the legislature’s first attempt to construct a defined contribution program. It was also a major attempt to reduce pension costs by increasing the FAC from 3 years to 5 years and eliminating the cost of living adjustments. Also, this membership group no longer is allowed to purchase years of service credit, which would have increased the YOS in the retirement formula. The generous MIP pension plan enacted in 1987 dramatically increased costs for the local public school district. A legislative maneuver in an attempt to decrease costs was to offer a concept known as an early retirement incentive (ERI). Included in the 2010 reform legislation was incentive for public school employees to retire by offering a 1.6% multiplier on the first $90,000 of FAC and a 1.5% on the remainder, rather than the normal 1.5% on the full amount. Conceptually, this reduced costs for school districts by reducing the number of employees on the payroll. However, the long-term cost increased because of more participants in the retirement system. These incentives also exacerbated 23 the issue of the declining number of workers per retiree, which in turn, increased the percentage of salary that local school districts had to pay into the retirement system. The issue of fewer workers per retiree was impacted by recommendations from the State legislature. They concluded it was a sagacious financial maneuver to contract for services for all non-certified positions, such as food service, custodial, maintenance, transportation and the like. Once again, this reduced short-term costs by lowering payroll, but long-term costs increased due to the rising unfunded liability of the pension system. Compounding the problem, enrollment in the majority of Michigan school districts declined over the past decade, which is requisite factor of the revenue allocated to local public schools. From 2004 through 2012, 425 of the 549 public school districts witnessed a decline in enrollment. Statewide enrollment over this period declined by 13.2%. One reason for this decrease in enrollment is the increased allowance of charter schools. Since 2004, the number of charter schools increased from 199 to 298. These schools enroll approximately 120,000 students, which equates to 9% of all public and charter school students in the state. 24 Very few of these charter schools participate in MPSERS. This drain of student enrollment decreases the number of teachers needed in traditional public schools, which, again, reduces the number of workers per retiree. Another issue leading to the funding problem is the increase in medical costs. Insurance rates have grown steadily, which increases the liability to MPSERS via retiree health care coverage and to local districts due to employee contractual agreements. 24 Cate Long, “Michigan’s Pension Problem,” Reuters, November 20, 2013. http://blogs.reuters.com/muniland/2013/11/20/michigans-pension-problem/ (accessed February 3, 2014). 24 In response to these increasing costs and unfunded accrued liability, the Michigan legislature enacted P.A. 300 of 2012. 25 This bill dramatically modified the school employee retirement system with a focus on reducing costs. Many of these costs were transferred to current and future retirees. 26 Current school employees had to make decisions concerning their pension plan. Basic and MIP employees hired prior to July 1, 2010 had to choose among four pension options: 1. Maintain the 1.5% multiplier and increase their contribution from 0 to 4% for Basic and between 3 and 6.4% to 7% for MIP members; 2. Increase contribution rates and maintain the 1.5% multiplier until the employee reaches 30 years of service, then move to a defined contribution plan with a 4% employer contribution; 3. Maintain current contributions and receive a reduced multiplier of 1.25%; or 4. Freeze existing pension and FAC and receive a flat 4% defined contribution for all future years of service. These Basic and MIP employees hired before July 1, 2010 also had to also choose between two retiree health care options: 1. Continue to pay 3% for retiree health insurance premium covered at 80%; 2. Discontinue paying 3% and opt out of the retiree health insurance program. Previous 3% contributions would go into a 401(K) type plan. Employers would then contribute a 100% match of the employee’s contribution up to 2% into this plan.27 For Pension Plus (Hybrid) employees hired after July 1, 2010 there was no change to the pension program. However, the health care program offered the same two options 25 Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System Reform of 2012. Public Act 300. Michigan Legislature. September 4. 26 Bethany Wicksall, Michigan Public School Employees’ Retirement System (MPSERS) Reform SB 1040 – PA 300 of 2012 (Lansing, MI: House Fiscal Agency, September 7, 2012) http://www.mcca.org/uploads/fckeditor//file/MCCA_MPSERS%20Reform%20Webinar(7).pdf (accessed February 2, 2014). 27 PA 300 of 2012. 25 as Basic and MIP. New employees hired after September 4, 2012 had to select between two retirement plan options: 1. Participate in the Pension Plus (Hybrid) plan with the same contribution rates of 6.4% for the pension component and the optional defined contribution match of up to 2% of compensation; 2. Choose a 401(K) type plan with an employer contribution equal to 50% of an employee’s contribution up to 6%.28 These same new employees will receive no health insurance from the retirement system. Instead they will receive a 100% employer match of an employee’s contribution up to a maximum of 2% of compensation into a 401(K) type plan. Additionally, upon retirement and reaching age 60, the employee will receive $1,000 or $2,000 (depending on whether they had more or less than ten years of service), deposited into a health reimbursement account. P.A. 300 of 2012 also impacted those currently retired. There was no change to the pension portion of the program, but health insurance was affected. Retirees who turned 65 by January 1, 2012 are required to pay 10% of the health insurance premium. Those turning 65 after January 1, 2012 must pay 20% of the premiums. Prior to P.A. 300, retirees paid no state income tax on their pensions – now they do.29 With these changes there will be an impact on the unfunded accrued liability and school costs. Employer’s contribution rates for the unfunded liability have been capped at 20.96% to 24.79% depending on the employee pension plan. It is estimated that these reforms will save $510 million in fiscal year 2015, which equals approximately $370 per 28 29 Ibid. Ibid. 26 student. It is also estimated that the unfunded accrued liability will be eliminated by the year 2039.30 The State of Michigan has taken major strides to eliminate a looming financial burden with these changes in the Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System. Even though there is an unfunded liability of $60 billion, the system does have assets of $43 billion making them one of the best-funded retirement systems in the United States. Even so, the Michigan had to do something to eliminate the increasing financial burden on local school districts created by the retirement system. At some point in the future, when all the current Basic and MIP matriculate through the system, school districts will only have the defined contribution rates as a liability, 4% of salary versus 24.9%. Florida The Florida Retirement System (FRS) for public educators is a prime example of a well-funded system that is meeting its statutory obligation. However, opponents of the retirement program cast hyperbole that purports a system at the precipice of utter ruination. Florida possesses an unfunded liability in its pensions system as is consistent with the majority of states. The state has a pension pool that is valued at $133.7 billion with a $19 billion dollar gap, which represents a system that is 87% funded – one of the best in that nation. In 2012 – 2013, the pension system exceeded estimates when the return on the investments was 11%. Although critics point to the fact the state must allocate $500 million to fund the liability, the pool is considered to be healthy. The FRS provides members with two choices for retirement: the Pension Plan and the Investment Plan. The Pension Plan provides members with a defined benefit program 30 Ibid. 27 and the Investment Plan is a defined contribution plan. The Pension Plan employs the following formula to determine benefits: Member Benefit = m(1.60%) CS FAS Where m is the percentage factor determined by the state, CS is the creditable service and FAS is the final average salary. The FAS is associated with the date of hire. If a member was hired prior to July 1, 2011, then the FAS is calculated based on the five highest salary years. If the hire date of the member is after July 1, 2011, then the FAS is calculated based upon the eight highest salary years. Employees are obligated to pay 3% of their salary to the retirement system and the State funds the remainder. For FY2014, the State of Florida required districts to pay 5.18% of an employee’s salary if he or she enrolled in the Investment Plan. For employees that enrolled in the Pension Plan, the local district is required to pay 6.95%.31 By state statute, the legislature establishes the required percentage each legislative session. In addition to employee and employer contributions, Florida appropriated $500 million for FY2014 to keep the retirement system solvent for future retirees. Deferred Retirement Option Program In 1998, Florida created a unique retirement program known as the Deferred Retirement Option Program, or more commonly known by its acronym, DROP. DROP effectively allows an employee to retire from the FRS, yet remain employed by a public school. The employee’s service credit ceases upon election of this option and the employee must sever all employment with a public school within 60 months.32 The value 31 Florida Senate. SB 1810. Florida Retirement System. 2013 Sess., http://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2013/1810 (accessed February 17, 2014). 32 FRS, FRS Today: Deferred Retirement Option Program, (Tallahassee, FL: Department of Management Services, 2013), 4 – 10. 28 to the employee is that he or she retains his or her normal salary and the retirement benefit that would normally be paid at the inception of retirement is placed in a FRS Trust Fund earning tax-deferred interest until the employee finalizes his or her eligibility (no more than 60 months) into the DROP program. The State is able to retain experience in the profession, limit the number of employees immediately retiring, and save costs. If a member entered the FRS prior to July 1, 2011, he or she must be 62 and vested with at least 6 years of service or 30 years of service at any age. If a member enrolled after July 1, 2011, the normal retirement age is 65 with 8 years to be vested. A member that has 33 years of service may enter DROP at any age.33 Time in Court – Commonality Among the Three States Illinois A unique, yet growing characteristic, is to seek redress in the state court system for perceived constitutional infractions relative to public pension systems. While multiple litigation permeates the judicial landscape on public educator retirement, the three states amplified in this analysis have had or are in the middle of litigious contests on multiple points of the growing angst of losing retirement benefits. The Illinois Teacher Retirement System is the system closest to the precipice of complete disaster. With the legislative passage of SB 1(PA 98-0599) and the subsequent signature of Governor Pat Quinn, those negatively affected by the decision immediately sought judicial relief. The union coalition, We Are One Illinois Coalition consists of multiple unions, which represent active and retired public employees. The suit contends that public employees and retirees, “...have upheld their end of that constitutionally-protected bargain” and the State has 33 FRS, Defined Retirement Option Program (Tallahassee, FL: Department of Management Services, 2013) http://www.myfrs.com/portal/server.pt/community/pension_plan/233/drop (accessed February 16, 2014). 29 engaged in “pension theft” by violating the constitutional clause which states that, “Membership in any pension or retirement systems of the State, any unity of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired”34 The suit continues: Those Plaintiffs who are current employees teach our children, care for the sick and disabled, protect us from harm and perform myriad other essential services for Illinois and its citizens. Those Plaintiffs who already have retired similarly dedicated their careers to the men, women and children of Illinois. And, each faithfully has contributed to his or her respective pension system the substantial portion of their paychecks the Illinois pension code requires.35 Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the State. The State chose to forgo funding its pension systems in amounts the State now claims were needed to fully meet the State’s annuity obligations. Now, the State expects the members of those systems to carry on their backs the burden of curing the State’s longstanding misconduct. Specifically, Public Act 980599 unlawfully strips from public servants pension amounts to which they otherwise are entitled as a matter of law, let alone fundamental fairness.36 That is the very threat against which the Pension Clause protects.37 The Governor and the members of the General Assembly took an oath to uphold the Constitution. They acknowledge that other options exist to remedy the State’s knowing failure to adequately fund the State’s pension systems. But rather than work to remedy the impact of the State’s conduct in a manner that comports with their oath, complies with the Illinois Constitution and upholds the State’s constitutional promise to pension system members, the Governor and General Assembly unlawfully look the other way.38 Plaintiffs thus turn to this Court for protection and commence this action to defend their constitutionally protected rights and protect the pensions 34 Ill. Const. 1970, art 12, sec. 5. Harrison, et al. v. Quinn, et al., No. 2014CHOOO48, 3 (7 th Cir. filed January 28, 2014). 36 Ibid. 37 Ibid., 4. 38 Ibid. 35 30 they have earned. Plaintiffs request that the Court declare Public Act 980599, in its entirety, unconstitutional, void and unenforceable. 39 We Are One Illinois Coalition pontificates to great measure that the constitutional provision developed in 1970 is a contract between the State and its public workers and this obligation may not be breached. The Coalition is anticipating the Illinois Supreme Court follow the theory of stare decisis et quieta non movere as the court has consistently struck down attempts to change the state’s pension laws when benefits are diminished as constitutional requirements cannot be suspended for economic reasons. 40 The State is contending the law is constitutional based upon the legal theory of “consideration.” 41 Current workers would pay 1% less toward their pensions which scales back an annual 3% compounded cost of living increase to retirees.42 In addition, the current reform also requires many current members to skip up to five annual cost of living increases when they retire. It also increases the retirement age by five years, depending upon the age of the member. The optimism shared among Coalition members needs to be tempered as litigation against state pension systems is prevalent and plaintiffs are not succeeding. In spite of the potential for case law in Illinois supporting the Coalition’s position, other states such as Michigan and Florida are demonstrating that state courts are endorsing the position of the respective state, finding that legislatures may, indeed, modify statutes and 39 Ibid. Rick Pearson, “Retired Teachers File First Lawsuit Against Illinois Pension Reform Law,” Chicago Tribune, December 28, 2013, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-12-28/news/chi-retired-teachers-filefirst-lawsuit-against-illinois-pension-reform-law-20131227_1_employee-pension-system-illinois-pensioncode-teacher-retirement-system (accessed February 24, 2014). 41 Consideration is the benefit that each party gets or expects to get from the contractual deal. In order for consideration to provide a valid basis for a contract, each party must make a change in their position. Consideration is usually either the result of a promise to do something not legally obligated to do or a promise not to do something you have the right to do. A unilateral promise is not a contract. 42 See Cola for Active and Retired Members. 40 31 constitutional language to alter the pension programs once thought an unalterable guarantee. Florida On July 1, 2011, the Florida Senate Bill 2100 was enacted, which required active members of the Florida Retirement System (FRS), which included public educators to give up 3% of his or her salary to a retirement contribution. Conservative factions mounted a campaign, which highlighted a retirement system that would become insolvent if not reformed. Governor Rick Scott promised to bring the Florida Retirement System more in line with other states and reduce costs to the system by $1.4 billion. The state district court found the legislation unconstitutional. The court declared the law took private property without full compensation. In light of this ruling, the State proceeded with an appeal to the Florida Supreme Court. In a 4-3 decision, the court concurred with the State and reversed the lower court’s ruling. 43 The court relied on a previous case, Florida Sheriffs Association v. Department of Administration, Division of Retirement44 for support in its verdict. Florida Sheriffs declared that, “Under the prior case law, if the retirement system was mandatory as it is now, the legislature could at any time alter the benefits retroactively or prospectively for active employees.” 45 That court concluded that the rule was, “…changed by the ‘ preservation of rights’ section which…vests all rights and benefits already earned under the present retirement plan so that the legislature may now only 43 Scott et. al. v. Williams et. al., 107 So. 3d 379 (2013). 408 So. 2d 1033, 1037 (Fla. 1981). 45 Ibid. 44 32 alter retirement benefits prospectively.”46 The court stated that, “the rights provision was not intended to bind future legislatures from prospectively altering benefits which accrue for future state service…[to hold otherwise would] impose on the state the permanent responsibility for maintaining a retirement plan which could never be amended or repealed irrespective of the fiscal condition of this state.”47 Thus, current members of the FRS system are now required to pay 3% of his or her salary for the benefit. Michigan The last several years have seen an increase in litigious activity in Michigan related to retirement benefits. Members of MPSERS have been witness to increases for membership and health insurance at retirement. The Plaintiffs in this contest employed the analogous argument as Illinois and Florida claiming “pension theft.” The primary Plaintiffs, the American Federation of Teachers and the Michigan Education Association purport the state unlawfully seized their members’ property and unjustly enriched the state. Two primary suits have been filed in Michigan. The first one was in response to an increase in member cost for health insurance upon retirement. Up to 2010, Michigan’s public school teachers were not required to pay for retirement health insurance. Public Act 77 (MCL 38.2731et seq.) states: Except as otherwise provided in this section, beginning July 1, 2010, each member shall contribute 3% of the member’s compensation to the appropriate funding account established under the public employee retirement health care funding act [MCL 38.2731 et seq.]. For the school fiscal year that begins July 1, 2010, members who were employed by a reporting unit [i.e., school district] and were paid less than $18,000.00 in the prior school fiscal year and members who were hired on or after July 1, 2010 with a starting salary less than $18,000.00 shall contribute 1.5% of the member’s compensation to the appropriate funding account established 46 47 Ibid. Ibid. 33 under the public employee retirement health care funding act. For each school fiscal year that begins on or after July 1, 2011 member’s compensation to the appropriate funding account established under the public employee retirement health care funding act. The member contributions shall be deducted by the employer and remitted as employer contributions in a manner that the retirement system shall determine.48 The Michigan Court of Appeals held for the Plaintiffs by concluding: We are not unmindful of the budgetary challenges facing local school districts and Michigan’s institutions of higher education. Moreover, we recognize that the State Legislature is within its authority to adopt legislation to aid these entities as they seek to address those budgetary challenges. In exercising that authority, however, the Legislature remains constrained by the state and federal Constitutions and the rights they guarantee. MCL 38.1343e violates multiple provisions of these Constitutions. Accordingly, we affirm the trial court’s orders granting summary disposition in favor of plaintiffs…49 The State is appealing the decision to the Michigan Supreme Court and as of this composition, a decision has yet to be rendered. As part of PA 300 of 2012, members of the public educator retirement plan were required to make a choice in terms of their future retirement pension benefits. The options are as follows: 1. Members of the Basic Plan, who historically contributed nothing to their pensions, would now be expected to contribute 4% of their income to their pensions. Those individuals hired between January 1990 and July 2010 and those former Basic Plan members who transferred into the Member Investment Plan (MIP) would increase their contribution to 7%. Members who opted into the Basic Plan and MIP Plan would maintain the current 1.5% multiplier; 2. Members could maintain current contribution rates, freeze existing benefits at the 1.5% multiplier, and receive a 1.25% pension multiplier 48 Public Employee Retirement Health Care Funding Act of 2010. Public Act 77. Michigan Legislature. December 15. http://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(utiyih45jntzya55pmeohx55))/mileg.aspx?page=getObject&objectName= mcl-Act-77-of-2010 (accessed February 25, 2014). 49 AFT Michigan, et al. v. State of Michigan et al. 1, 18 (Mich. App., 2012) http://www.freep.com/assets/freep/pdf/C4193517817.PDF (accessed February 26, 2014). 34 for future years of service; 3. Members could freeze existing pension benefits and move into a defined contribution, 401(k)-style, plan with a flat 4% employer contribution for future service.50 In addition, members were asked to “opt in” or “opt out” of retiree healthcare benefits; members could either contribute 3% of their compensation receive the future benefit, or they could choose to receive no retiree healthcare benefits at retirement. 51 On all challenges the court agreed with the State’s position and ultimately concluded that PA 300 of 2012, “…neither unlawfully takes members’ property nor does it amount to unjust enrichment.”52 Thus, members are now bound by this legislation. The contests in Illinois, Florida, and Michigan demonstrate the current jurisprudential climate regarding state legislatures modifying public school employees’ retirement packages. Legislatures are purporting good public policy to reduce retirement benefits that are no longer affordable while members of retirement programs contend that a form of governmental theft is occurring. Currently, state courts seem to be concurring with state positions. Conclusion This thesis yields several incontrovertible conclusions. One, in each state pension plans are reaching a demarcation where the state will not be able to fund future retirees’ pensions. Two, state legislatures envisage a retirement system that is vastly different than the historical defined benefit plan, aligning the plan with private sector programs. In some states, the unfunded liability is reaching the precipice of bankruptcy and needs to be 50 AFT Michigan et al. v. State of Michigan et al. 1,7 (Mich. 2014) January 14. Ibid. 52 Ibid., 20. 51 35 reformed. In other states, the pension system is healthy, yet politicians seek to modify it on the supposition that a system that is not fully funded is bound for disaster. These legislators exploit the naiveté of citizens who are less informed about the issue. Each individual state requires close scrutiny to assess the actual performance of its retirement system. Third, defined contribution programs or variants appear to be the primary method for reform. Within this modification, retirees are seeing loss of benefits or age thresholds that are increasing. Those individuals that are being affected by these changes will continue to bring forth litigious challenges that are focused on perceived state constitutional guarantees or promises. At this juncture, it appears as though state supreme courts are holding that state legislatures are on constitutionally solid ground to modify these programs, especially for future retirees. 36 References Cavanaugh, Sean. “Personnel Costs Prove Tough to Contain.” Education Week, January 5, 2011. http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2011/01/13/16personnel.h30.html?utm_source =fb&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=mrss (accessed February 8, 2014). Costrell, Robert M. and Michael Podgursky. “Distribution of Benefits in Teacher Retirement Systems and Their Implication for Mobility.” Journal of Education Finance and Policy 5 (Fall 2010): 519-557. Derringer, Nancy. “Teacher Retirement Fund Has $45 Billion Hole.” Bridge Magazine. April 24, 2012. http://bridgemi.com/2012/04/teacher-retirement-fund-has-45billion-hole/ (accessed January 13, 2014). Eisele-Dyrli, Kurt. “Will Pensions Bankrupt Your District?: State Retirement Funds are in Crisis, and School Systems Will Likely Pay More of the Bill.” District Administration (January 2010). http://www.districtadministration.com/article/will-pensions-bankrupt-your-district (accessed October 27, 2013). Financial Services for Office of Retirement Services. Michigan Public School Employees Retirement Services: Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2013. Lansing, MI: MPSERS, 2013. FRS. FRS Today: Deferred Retirement Option Program. (Tallahassee, FL: Department of Management Services, 2013). FRS. Defined Retirement Option Program. (Tallahassee, FL: Department of Management Services, 2013). http://www.myfrs.com/portal/server.pt/community/pension_plan/233/drop (accessed February 16, 2014). Gantert, Tom. “Public School Pension System Totally Broken: Taxpayers on the Hook for Billions in Unfunded Liabilities.” CAPCON: Michigan Capitol Confidential. June 24, 2013. http://www.michigancapitolconfidential.com/18797 (accessed on February 3, 2014). Hess, Frederick M. and Juliet P. Squire. “The False Promise of Public Pensions.” Policy Review 158 (December 2009/January 2010). http://www.hoover.org/publications/policyreview/72861002.html (accessed November 3, 2013). Lafferty, Michael B., Chester E. Finn, Jr., Janie Scull and Amber M. Winkler. Halting a Runaway Train: Reforming Teacher Pension for the 21st Century. Washington, D. C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2011. 37 Long, Cate. “Michigan’s Pension Problem.” Reuters. November 20, 2013. http://blogs.reuters.com/muniland/2013/11/20/michigans-pension-problem/ (accessed February 3, 2014). MPSERS. Major Changes in Recent Years and More to Come. (Lansing, MI, 2012). www.pscinc.com (accessed January 13, 2014). Office of Retirement Services. Michigan Public School Employees Retirement Service. http://www.michigan.gov/orsschools (accessed February 19, 2014). Pearson, Rick. “Retired Teachers File First Lawsuit Against Illinois Pension Reform Law.” Chicago Tribune. December 28, 2013. http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-12-28/news/chi-retired-teachers-file-firstlawsuit-against-illinois-pension-reform-law-20131227_1_employee-pensionsystem-illinois-pension-code-teacher-retirement-system (accessed February 24, 2014). Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois. New Pension Benefit Law for TRS January 31, 2014. http://trs.illinois.gov/press/reform/sb1.htm (accessed February 10, 2014). The Pew Center on the States. The Widening Gap: The Great Recession’s Impact on State Pension and Retiree Healthcare Costs. Washington, D. C.: Pew Research Center, 2011. http://www.pewcenteronthestates.org (accessed September 12, 2013). Toutkoushian, Robert K., Justin M. Bathon and Martha M. McCarthy. “A National Study of the Net Benefits of State Pension Plans for Educators.” Journal of Education Finance 37 (Summer 2011): 24-51. Wicksall, Bethany. “Michigan Public School Employees’ Retirement System (MPSERS) Reform SB – PA 300 of 2012. September 7, 2012. http://www.mcca.org/uploads/fckeditor//file/MCCA_MPSERS%20Reform%20W ebinar(7).pdf (accessed February 2, 2014). 38