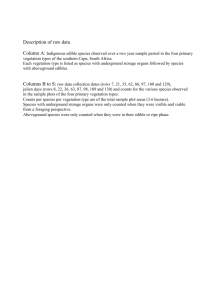

Great Divide fire recovery plan - Department of Environment, Land

advertisement