Chronic Gastritis

advertisement

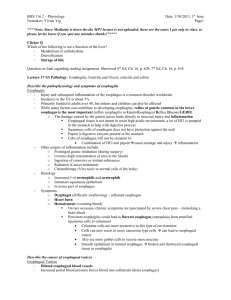

GASTRITIS lec.3 Dr.Maha Acute Gastritis Acute gastritis is an acute mucosal inflammatory process, usually of a transient nature. The inflammation may be accompanied by hemorrhage into the mucosa and, in more severe circumstances, by sloughing of the superficial mucosal epithelium (erosion). This severe erosive form of the disease is an important cause of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Acute gastritis is frequently associated with the following: • Heavy use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly aspirin. • Excessive alcohol consumption • Heavy smoking • Treatment with cancer chemotherapeutic drugs • Uremia • Severe stress (e.g., trauma, burns, surgery) Chronic Gastritis Presence of chronic mucosal inflammation leading eventually to mucosal atrophy and epithelial metaplasia. Pathogenesis: 1- Most important etiology is H.pylori chronic infection in areas where the infection is endemic H. pylori is a noninvasive, non—spore forming, S-shaped gram-negative rod. gastritis develops owing to the:1- combined influence of bacterial enzymes and toxins , 2- release of noxious chemicals by the recruited neutrophils. Patients with chronic gastritis and H. pylori usually improve symptomatically when treated with antimicrobial agents. 2- Other forms of chronic gastritis are much less common is autoimmune gastritis, which results from autoantibodies to the gastric gland parietal cells. The autoimmune injury leads to gland destruction and mucosal atrophy, with concomitant loss of acid and intrinsic factor 1 production. The resultant deficiency of intrinsic factor leads to pernicious anemia MORPHOLOGY Regardless of the cause or histologic distribution of chronic gastritis, the inflammatory Changes consist of: 1- a lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate in the lamina propria. 2- variable gland loss and mucosal atrophy. 3- When present H.pylori organisms are found nestled within the mucus layer overlying the superficial mucosal epithelium. 4- In the autoimmune variant, loss of parietal cells is particularly prominent. 5- Two additional features are of note, 1st Intestinal metaplasia refers to the replacement of gastric epithelium with columnar and goblet cells of intestinal variety. This is significant, because gastrointestinal-type carcinomas appear to arise from dysplasia of this metaplastic epithelium. Second, H. pylori induced proliferation of lymphoid tissue within the gastric mucosa has been implicated as a precursor of gastric lymphoma. ****When severe parietal cell loss occurs in the setting of autoimmune gastritis, hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria occur. Most important is the relationship of chronic gastritis to the development of peptic ulcer and gastric carcinoma, Most patients with a peptic ulcer, whether duodenal or gastric, have H. pylori infection. For autoimmune gastritis, the risk for cancer is in the range of 2% to 4% of affected individuals, which is well above that of the normal population. Helicobacter pylori gastritis. A Steiner silver stain demonstrates the numerous darkly stained organisms along the luminal surface of the gastric epithelial cells. Note that there is no tissue invasion by bacteria. Small and Large Intestines 2 DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES . • Meckel diverticuluin is the most common and innocuous of the anomalies. It results from failure of involution of the omphalomesenteric duct, leaving a persistent blind-ended tubular protrusion up to 5 to 6 cm long. The diameter is variable. Usually in the ilium, and composed of all layers of small intestine. They are generally asymptomatic Meckel diverticulum. The blind pouch is located on the antimesenteric side of the small bowel. Hirschsprung Disease: Congenital Megacolon Distention of the colon to greater than 6 or 7 cm in diameter (megacolon) occurs as a congenital and as an acquired disorder. Hirschsprung disease (congenital megacolon) results during development, the caudal migration of neural crest—derived cells along the alimentary tract arrests at some point before reaching the anus. Hence, an aganglionic segment is left that lacks both the Meissner submucosal and Auerbach myenteric plexuses. This causes functional obstruction and progressive distention of the colon proximal to the affected segment. In most instances, only the rectum and sigmoid are aganglionic, but in about a fifth of cases a longer segment, and rarely the entire colon, is affected. Approximately 50% of cases result from mutations in RET gene. Acquired megacolon may result from (1) Chagas disease, in which the trypanosomes directly invade the bowel wall to destroy the plexuses, (2) organic obstruction of the bowel by a neoplasm or inflammatory stricture, (3) toxic megacolon complicating ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease (discussed later), or (4) a functional psychosomatic disorder. 3 Malabsorption Syndromes and diarrhea Malabsorption, which presents most commonly as chronic diarrhea, is characterized by defective absorption of fats, fat- and water-soluble vitamins, proteins, carbohydrates, electrolytes and minerals, and water. Chronic malabsorption can be accompanied by weight loss, anorexia, abdominal distention. A hallmark of malabsorption is steatorrhea, characterized by excessive fecal fat and bulky, frothy, greasy, yellow or clay-colored stools. Most common type: Gluten-sensitive enteropathy, also known as celiac disease, is the prototype of a noninfectious cause of malabsorption resulting from a reduction in small intestinal absorptive surface area. The basic disorder in celiac disease is sensitivity to gluten, the component of wheat and related grains (oat, barley, and rye) that contains the water-insoluble protein gliadin. There is autoimmune mechanism responsible of development of such disease. The small intestinal mucosa, when exposed to gluten, accumulates large numbers of B cells and plasma cells sensitized to gliadin; accumulation of lymphocytes in gastric and colonic mucosa also may occur. In addition to filling the lamina propria, lymphocytes also cross into the epithelial space, with accompanying damage to surface enterocytes. Total flattening of mucosal villi (and hence loss of surface area) is the outcome, affecting the proximal more than the distal small intestine. The age of presentation with symptomatic diarrhea and malnutrition varies from infancy to mid adulthood; removal of gluten from the diet is met with dramatic improvement. There is, however, a low long-term risk of malignant disease on the order of a two-fold increase over the usual rate. Intestinal lymphomas, especially T-cell lymphomas, are disproportionately represented; other malignancies include gastrointestinal and breast carcinomas. IDIOPATHIC INFLAMMATOR Crohn Disease 4 BOWEL DISEASES This disease may affect any level of the alimentary tract, from mouth to anus. Active cases of CD are often accompanied by extraintestinal manifistations of immune origin, such as iritis and uveitis, sacroiliitis, migratory polyarthritis, erythema nodosum, hepatic pericholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis (bile duct inflammatory disorders), and obstructive uropathy. Systemic amyloidosis is a rare late consequence. Thus, CD must be viewed as a systemic inflammatory disease with predominant gastrointestinal involvement. Epidemiology. Worldwide in distribution, CD is much more prevalent in the United States, Great Britain and is rare in Asia and Africa. It occurs at any age, from young childhood to advanced age, but the peak incidence is between the second and third decades of life. Females are affected slightly more often than males. Whites appear to develop the disease two to five times more often than do nonwhites. MORPHOLOGY In CD, there is gross involvement of the small intestine alone in about 30% of Cases, of small intestine and colon in 40%, and of the colon alone in about 30%. When fully developed, CD is characterized by (1) sharply delimited and typically transmural involvement of the bowel by an inflammatory process with mucosal damage, (2) the presence of noncaseating granulomas in 40% to 60% of cases, and (3) fissuring with formation of fistulae. In diseased segments hypertrophy of the muscularis propria. As a result the lumen is almost always narrowed; in the small intestine this is evidenced radiagraphically as the “string sign,” a thin stream of barium passing through the diseased segment. Strictures may occur in the colon but are usually less severe. A classic feature of CD is the sharp demarcation of diseased bowel segments from adjacent uninvolved bowel. When multiple bowel segments are involved, the intervening bowel is essentially normal (“skip” lesions). In the intestinal mucosa, early disease exhibits focal mucosal ulcers resembling canker sores (aphthous ulcers). With progressive disease, ulcers coalesce into long, serpentine linear ulcers, which tend to be oriented along the axis of the bowel, because the intervening mucosa tends to be relatively spared, it acquires a coarsely textured, cobblestone appearance. Narrow fissures develop between the folds of the mucosa, often penetrating deeply through the bowel wall all the way to serosa. Further extension of fissures leads to fistula or sinus tract formation, either to an adherent viscus, to the outside skin, or into a blind cavity to form a localized abscess. 5 By microscopic examination, the mucosa exhibits several characteristic features : (1) inflammation, with neutrophilic infiltration into the epithelial layer and accumulation within crypts to form crypt abscesses; (2) ulceration, which is the usual outcome of active disease: and (3) chronic mucosal damage in the form of architectural distortion, atrophy, and metaplasia. (4) Granulomas may be present anywhere in the bowel segment. However, the absence of granulomas does not preclude a diagnosis of CD. (5) In diseased segments. the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria are usually markedly thickened, and fibrosis affects all tissue layers. (6) Lymphoid aggregates scattered through the various tissue layers and in the extramural fat also are characteristic. (7) Particularly important in patients with long-standing chronic disease are dysplastic changes appearing in the mucosal epithelial cells. It is related to a five-told to six-fold increased risk of carcinoma, particularly of the colon. 6 Crohn disease of the colon showing a deep fissure extending into the muscle wall, a second, shallow ulcer (and relative preservation of the intervening mucosa). Abundant lymphocyte aggregates are present, evident as dense blue patches of cells at the interface between mucosa and submucosa Clinical Features. The presentation of CD is highly variable and ultimately unpredictable. The dominant manifestations are recurrent episodes of diarrhea, crampy abdominal pain, and fever lasting days to weeks. Ulcerative Colitis Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an ulceroinflammatory disease affecting the colon but limited to the mucosa and submucosa except in the most severe cases. UC begins in the rectum and extends proximally in a continuous fashion, sometimes involving the entire colon. Like CD, UC is a systemic disorder associated in some patients with migratory polyarthritis, sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis, erythema nodosum, and hepatic involvement (pericholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis). There are several important differences between UC and CD: 7 • In UC, well-formed granulomas are absent. • UC does not exhibit skip lesions. • The mucosal ulcers in UC rarely extend below the submucosa, and there is surprisingly little fibrosis. • Mural thickening does not occur in UC, and the serosal surface is usually completely normal. • Patients with UC are at greater risk for carcinoma. Epidemiology. UC is somewhat more common than CD in the United States and Western countries, but it is infrequent in Asia, Africa, and South America. 8 MORPHOLOGY At the time of diagnosis, UC involves the rectum or rectosigmoid colon only in about 50% of cases; presentation with pancolitis occurs much less frequently. Colonic involvement is continuous from the distal colon, so that “skip lesions are not encountered. Active disease denotes ongoing inflammatory destruction of the mucosa, with macroscopic hyperemia, edema, and granularity with friability and easy bleeding. With severely active disease, there is extensive and broad-based ulceration of the mucosa in the distal colon or throughout its length . Isolated islands of regenerating mucosa bulge upward to create pseudopolyps. but rarely do they replicate the linear serpentine ulcers of CD. In rare cases, the muscularis propria is so compromised as to permit perforation and pericolonic abscess formation. When this occurs, the colon progressively swells and becomes gangrenous (toxic megacolon). With indolent chronic disease or with healing of active disease, progressive mucosal atrophy leads to a flattened and attenuated mucosal surface. Microscopical features of UC are those of mucosal inflammation, ulceration, and chronic mucosal damage . Neutrophilic infiltratian of the epithelial layer may produce collections of neutrophils in crypt lumina (crypt abscesses), these are not specific for UC . There are no granulomas. with remission of active disease, granulation tissue fills in the ulcer craters, followed by regeneration of the mucosal epithelium. 9 The most serious complication of UC is the development of colon carcinoma. Two factors govern the risk: duration of the disease and its anatomic extent. It is believed that with 10 years of disease limited to the left colon the risk is minimal, and at 20 years the risk is on the order of 2%, With pancolitis, the risk of carcinoma is 10% at 20 years and 15% to 25% by 30 years. 10 Clinical Features. UC is a chronic relapsing and remitting disorder marked by attacks of bloody mucoid diarrhea that may persist for days, weeks, or months and then subside, only to recur after an asymptomatic interval of months to years or even decades. Uncommon but life-threatening complications include: severe diarrhea and electrolyte derangements, massive hemorrhage, severe colonic dilation (toxic megacolon) with potential rupture, and perforation with peritonitis. 11