Dear Notetaker:

advertisement

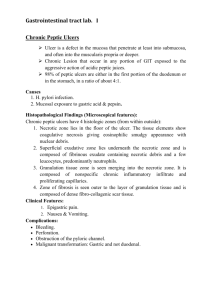

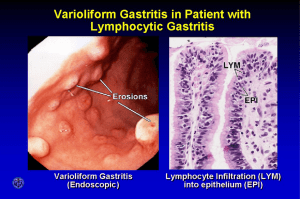

BHS 116.2 – Physiology Notetaker: Vivien Yip Date: 1/30/2013, 1st hour Page1 ****Note: Since Mediasite is down the the MP3 lecture is not uploaded, these are the notes I got only in class, so please let me know if you spot any mistakes thanks!***** Clicker Q Which of the following is not a function of the liver? - Metabolism of carbohydrate - Detoxification - Storage of bile Question on final regarding reading assignment: Sherwood 8th Ed, Ch. 16, p. 629; 7th Ed, Ch. 16, p. 634 Lecture 17 GI Pathology: Esophagitis, Gastritis and Ulcers, enteritis and colitis Describe the pathophysiology and symptoms of esophagitis Esophagitis - Injury and subsequent inflammation of the esophagus is a common disorder worldwide - Incidence in the US is about 5% - Primarily limited to adults over 40, but infants and children can also be affected - While many factors can contribute to developing esophagitis, reflux of gastric contents in the lower esophagus is the most important (reflux esophagitis or GastroEsophageal Reflux Disease/GERD) o The damage caused by the gastric juices leads directly to mucosal injury and inflammation Esophageal tissue is not meant to resist high acidic environment, a lot of HCl is pumped in the stomach to help with digestive process Squamous cells of esophagus does not have protection against the acid Pepsin is digestive enzyme present in the stomach Cells of esophagus will not be resistant to: Combination of HCl and pepsincauses damage and injury inflammation - Other origins of inflammation include: o Prolonged gastric intubation (during surgery) o Uremia (high concentration of urea in the blood) o Ingestion of corrosive or irritant substances o Radiation (Cancer treatment) o Chemotherapy (Very toxic to normal cells of the body) - Histology o Increased # of eosinophils and neutrophils o Immature squamous epithelium o In lower part of esophagus - Symptoms o Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) – inflamed esophagus o Heart burn o Hematemesis (vomiting blood) On rare occasion, chronic symptoms are punctuated by severe chest pain – mimicking a heart attack Persistent esophagitis could lead to Barrett esophagus (metaplasia from stratified squamous cells to columnar) Columnar cells are more protective in this type of environment Cells can now resort to more cancerous type cells can lead to esophageal cancer Also see more goblet cells to secrete more mucous Smooth epithelium in normal esophagus broken and destroyed esophageal tissue in esophagitis Describe the causes of esophageal varices Esophageal Varices - Dilated esophageal blood vessels - Increased portal blood pressure forces blood into collaterals (drain esophagus) BHS 116.2 – Physiology Notetaker: Vivien Yip - - Date: 1/30/2013, 1st hour Page2 o When these include the esophageal mucosal plexus, dilated tortuous vessels develop called varices Caused by any factor that creates portal hypertension o Most often cirrhosis of the liver 65% of cirrhotic patients develop varices o Portal hypertension backs up the collaterals and cause dilations of blood vessels in the lumen of the esophagus These varices are symptomless until they rupture and cause massive hematemesis o Then you get coughing/vomiting large amounts of blood Death results in about 20-30% of those patients who rupture due to fatal loss of blood Describe the differences between the types of hiatal hernias Hiatal Hernia - Another esophageal issue - Gastroesophageal junction is where the esophagus links up with the stomach - Stomach should be BELOW the diaphragm (normal) - Hiatal hernia is a dilated segment of the stomach that protrudes above the diaphragm o Incidences increase with age (seen much more with older adults) - 2 types: - 1. Sliding hernia o 95% of cases o Bell shaped dilation - 2. Paraesophageal hernia o Portion of the greater curvature of the stomach enters the thorax o Much more dangerous type* o Potential strangulation of blood vessels that run along the greater curvature of the stomach o If that part of the stomach bulges up above the diaphragm, the diaphragm can block those blood vessels o Potential for ischemia and death of stomach cells - Symptoms o Both types have mucosal ulceration, bleeding and perforation on occasion o Heartburn and regurgitation (reflux) are not symptoms caused by the hernia Only 9-10% of patients have this o Paraesophageal hernias can become strangulated and if undetected, ischemic Can be detected with barium Describe the pathophysiology of chronic and acute gastritis and their differences Gastritis - Defined as inflammation of the gastric mucosa - Most cases are chronic, but some are acute Acute gastritis o o - - Transient (can be cured and gone- non persistent) may be accompanied by hemorrhage into the mucosa and if severe, sloughing of superficial mucosa (erosion) o can lead to acute GI bleeding Symptoms o Asymptomatic OR: o Epigastric pain (upper region of abdominal area) o Nausea o Vomiting o Hemorrhage (occasional) o Hematemesis (vomiting large amounts of blood) and potentially fatal blood loss Approximately 25% of patients who take daily aspirin for rheumatoid arthritis (or any other inflammatory disease) develop acute gastritis at some time in their life Often associated with o Drugs: BHS 116.2 – Physiology Notetaker: Vivien Yip - - Date: 1/30/2013, 1st hour Page3 NSAIDS Chemotherapy drugs (can cause esophagitis and acute gastritis) o Alcohol o Smoking o Stress (trauma, burns, surgery) High amounts of cortisol can lead to stomach secretions Knocks down immune system making the stomach more susceptible to damage o Infections (systemic: salmonellosis) o Ischemia Often results in: o Increased acid secretion o Concomitant decrease in bicarbonate secretion pH will decrease, stomach cannot protect itself from the acidic environment o Decreased blood flow (resulting in ischemia) As tissues die, the mucus producing cells die along with them o Disruption of the protective mucus layer o Direct damage to the epithelium Since protective layers are absent All of these can act synergistically to worsen the injury to the gastric mucosa Can see large areas of gastric hemorrhage also known as erosions (superficial mucosa is eroded away) Chronic gastritis - More common form of gastritis - Chronic mucosal inflammatory changes, leading to mucosal atrophy and epithelial metaplasia o Defenses will be down o Cell will change type to make a more protective cell type to withstand the damage o Metaplasia causes change in cell type - Chronic changes in the epithelium, becoming dysplastic, may constitute a background for the development of gastric carcinoma - In Western cultures, histopathologic changes indicative of chronic gastritis are found in 50% of the population in later life (autopsy) o Undiagnosed until death - Frequent causes o Chronic helicobacter pylori infection o Autoimmune destruction of parietal cells in association with pernicious anemia o Toxicity Alcohol and smoking o Mechanical trauma o Radiation treatment (cancer treatment) o Post-surgical Surgery in abdominal region can disrupt stomach function and can lead to chronic gastritis Helicobacter Pylori - The most important of these associations is the chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori - This bacteria is present in 90% of patients with chronic gastritis affecting the antrum - Colonization increases with age reaching about 50% in US adults over 50yo - Most infected persons are asymptomatic o Drugs to eradicate H. pylori are critical in effective treatment of chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer o Easily treated with antibiotics Chronic gastritis - Continued inflammation of mucosa leads gradually to gastric atrophy - Leads to loss of stomach secretions - Achlorhydria (autoimmune)/Hypochlorhydria o Direct attack on parietal cells BHS 116.2 – Physiology Notetaker: Vivien Yip Date: 1/30/2013, 1st hour Page4 When stomach pH can’t get below 6.5 after maximal gastric stimulation due to lack of HCl secretion by parietal cells o Produce very little if any HCl o Not conversion of pepsinogen to pepsin o No protein digestion (pepsin activates other enzymes) o More susceptible to other bacterial infections (usually died off in acidic environment) Reduced HCl is hypochlorhydria o Leads to some digestive issues Pernicious anemia o Related to Vit B12 absorption due to decreased intrinsic factor production by parietal cells (usually only caused by autoimmune form) o - - Normal mucosa, always is going to be in contact with damaging factors: HCl, pepsin, physical movement, drugs, are damaging to the mucosal layer of the stomach - Typically have protection in place - When damaging factors are present With Chronic Gastritis, start to get changes in mucosal layer - Atrophy: don’t see much involution in the chronic gastritis - Mucosal layer do not have neutrophils in the normal gastric mucosa - Metaplasia into more protective cell type - Can easily seen with biopsy of stomach lining Describe the pathophysiology of peptic ulcers Peptic Ulcer - Remitting, relapsing lesions o Develop, heal, later months/years, back again - An excoriated (raw irritated worn off area) area of the mucosa caused by the digestive action of the gastric juices - Erosion of epithelium, submucosa and mucosal layers - Location: o Any GI tract portion o Most frequent in 1st portion of duodenum (80%) Chyme coming out of the stomach is most acidic and hits this part of the intestines first If we don’t get enough bicarb from the pancreas secreted early enough, will get break down o Antral portion of stomach Region before the small intestine o Gastroesophageal junction Where esophagitis also occurs - In Western nations, peptic ulcers develop in up to 10% of the population at some point during life - In the US ~4million people have peptic ulcers - 3000 people die each year due to complications o Sepsis and massive bleeding BHS 116.2 – Physiology Notetaker: Vivien Yip - - Date: 1/30/2013, 1st hour Page5 Likelihood of developing an ulcer is ~10% for US males and 4% for US females Appear to be produced by an imbalance between the GI defense mechanisms and the damaging forces Gastric acid and pepsin are requisite for all peptic ulceration o Physically break down and destroy the mucosa o Damage is due to the gastrin and HCl on the mucosa H. pylori is found in virtually all duodenal ulcers and in 70% of gastric ulcers o All duodenal peptic ulcers will have H. pylori o H. pylori can break down protective mechanisms of stomach o Recent work has focused on how the bacteria breaks down the mucosal defenses Induces inflammatory and immune responses Secretes toxins - Normal balance between aggressive and defensive forces - Peptic ulcers are created due to an impaired defensive force o Even normal aggressive force is strong enough to deterioriate epithelium of the stomach - Adding of aggravating causes will contribute to the formation of peptic ulcers - Result in degeneration of epithelium and mucosa - - - Chronic gastritis: alteration in mucosal layer, metaplasia, all restricted to the mucosal layer* Peptic ulceration: goes completely through mucosal layer, eats through muscularis mucosa, starts to damage to submucosa to the point where there is an inflammation causing fibrosis in the submucosal layer of the stomach Digestive juices will continue to eat their way through all the layers, nothing to stop the gastrin and pepsin action of mechanism Treatment of Peptic Ulcer - Many drugs are useful to allow healing of the mucosal damage o Antibiotics: eliminate H. pylori o Acid suppressant drugs: omeprazole o Histamine 2 blockers: cimetidine Triggers HCl release, therefore blocking histamine blocks HCl release o Acid neutralizers: antacids o Drugs to increase the barrier: sucralfate - Avoidance of secretogogues BHS 116.2 – Physiology Notetaker: Vivien Yip Date: 1/30/2013, 1st hour Page6 Describe the pathophysiology of infectious enterocolitis and ulcerative colitis Infectious enterocolitis - Intestinal disease o Consisting of diarrhea and sometimes uclers or inflammation of the small or large intestine Viral gastroenteritis Typically destroy epithelium and prevent absorption of fluid and nutrients Small and large intestines Bacterial enterocolitis Can proliferate in lumen and release an enterotoxin (toxigenic) or can directly destroy epithelium (enteroinvasive) Alternatively one can ingest a preformed toxin Don’t invade the cell, but releases toxic agents Enterotoxin acts on epithelium of small intestines Enteroinvasive bacteria gets inside the cells and destroy them - Many infectious organisms can lead to diarrhea o Most frequent Viral rotavirus (infants and toddlers) Norwalk virus (older children and adults) Bacterial enterotoxigenic e. coli (produces toxic protein) enteroinvasive salmonella (directly invades and destroys the cell- much more serious) o Worldwide – 12, 000 deaths per day (dehydration from severe diarrhea and unable to retain the fluids) among children in developing countries. 50% of all deaths worldwide in children under age 5 o In developed nations – still see average of 2 cases per person per year, second only to the common cold in frequency - In 40-50% of cases no specific infectious agent can be identified o Pathologic manifestations are as variable as the infectious sources o Can be viral or parasitic or bacterial - Clinical features of bacterial enterocolitis (most common type) o Ingestion of pre-formed bacterial toxins (food poisoning) o Symptoms develop in a matter of hours, with explosive diarrhea and acute abdominal distress o Some bacterial neurotoxins can lead to rapid death (botulinum toxin) o Most affects the GI epithelium - End result is loss of fluid (dehydration) o Sometimes so severe that death ensues o Short term complication - Cell damage or destruction of the intestinal mucosa which could lead to sepsis and perforation - Additionally, malabsorption of nutrients can occur due to shortened transit times and tissue damage and inflammation o Long term complication Malnutrition Damage to epithelium: sepsis Broken wall through intestine Intestinal content and bacterial leak out to abdominal cavity - Parasitic disease and protozoal infections affect more than half the world population on a chronic or recurrent basis o Nematodes (roundworms) o Flatworms (tapeworms and flukes) o Protozoa (crytosporidia) o Amebic dysentery (Entamoeba) o Giardia (fairly prevalent in the outdoors) BHS 116.2 – Physiology Notetaker: Vivien Yip Date: 1/30/2013, 1st hour Page7 Describe the 2 inflammatory bowel diseases- Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative colitis Crohn’s Disease - Idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease o Unknown cause, abnormal local immune response, CD4+ T-cell mediated o Genetic predisposition o Chronic and relapsing disorder, lasts for long period of time but will have bouts of symptoms, no symptoms, keeps coming back o Granulomatous: involves entire GI tract, but most often the intestines (sm & lg) Ileum is most common site o Ocular involvement (iritis and uveitis) - Inflammation and ulceration of the GI tract - Symptoms: o Diarrhea, fever lasting days to weeks, and abdominal pain - Mucosal surface demonstrates an irregular nodular appearance (granulomas) with hyperemia (blood) and focal superficial ulceration Ulcerative Colitis - Idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease - Colitis: restricted to large intestine and colon - Unknown cause, strong hereditary component, abnormal local immune response CD4+ Tcell mediated - Extensive areas of the colon become inflamed and ulcerated - Leads to excessive motility and enhanced secretions: diarrhea - Non-granulomatous - Ocular symptoms may include uveitis - Mucosa becomes eroded, remaining islands of mucosa are called pseudopolyps (little islands of normal mucosa) Crohn’s Disease vs Ulcerative Colitis Crohn’s disease Ulcerative colitis - Transmural and involve all 3 linings of the - Primarily affect the mucosa and submucosa wall - Does not affect muscularis mucosa - Inflammation affects all 3 layers - Erosion of the layers - Skip lesions: regions of diseased tissues - Get pseudopolyps followed by regions of normal tissue - Only in colon (large intestine) - Continuous legions of affected tissue - Not continuous - Large and Small intestine - Primarily in ileum Clicker Q - H. Pylori could cause all of the following except o Ulcerative Colitis