Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 ISSUE TRACE

advertisement

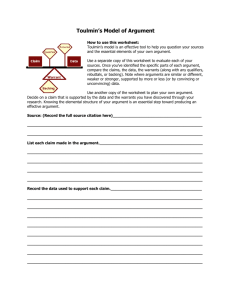

Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 ISSUE TRACE—ARRANGEMENT In high-school and college classrooms across the United States, students learn how to write essays and term papers according to a certain order: 1) Introduction; 2) Thesis; 3) Evidence; and 4) Conclusion. As we will see shortly, this sample argument model, far from being a modern concept, actually dates back to Ancient Greece. In addition, we will explore arrangement’s revision during the Renaissance, its revival and further development in the late 20th century, and finally, its diversification in the first decades of the 21st century. Arrangement, as a rhetorical concept, has a long, complicated history but continues to evolve to meet the needs of today’s students. Origins Arrangement, known in Ancient Greek as dispositio, was the second of the five canons of rhetoric and was concerned with effectively organizing discourse. The manner through which this discourse is organized varied among rhetoricians. For example, Aristotle, in Book III of Rhetoric, proclaimed that arrangement consisted of only two parts: statement and proof (Corbett 36). Despite Aristotle’s assertion, however, he was, according to Edward P. J. Corbett, “ready to concede that in practice, orators added two more parts: an introduction and a conclusion (36). The Latin text, Rhetorica Ad Herennium, by contrast, called for an arrangement that consisted of six parts: introduction (exordium); statement or exposition of the case under discussion (narratio); outline of the points or steps in the argument (divisio); proof of the case (confirmatio); refutation of the closing arguments (confutatio); and the conclusion (peroratio) (Corbett 36). The first part, exordium, or introduction, served to introduce the reader to the topic or argument. In an introduction a writer could use a hypothetical question or a quote. The 1 Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 utilization of either of these could be an effective tool to draw the reader into the topic. Indeed, according to Edward P. J. Corbett, “without this kind of ‘ornamental’ introduction, the discourse would have an abrupt, negligent, unfinished air about it” (304). The second part of arrangement, narratio, or statement of the facts, was concerned with the introduction of the facts that established an argument. Originally, narratio “figured principally in forensic oratory” (Corbett 314), as stating facts was necessary in establishment of the case. The third part, divisio, or outline of the argument, was the operation “throughout the whole discourse” (Porter 192). Essentially, this part of arrangement was concerned with the proper order and listing of the facts presented in written discourse. The fourth part, confirmatio, or confirmation, established proof of the facts. This part of arrangement could be considered as the core, since it established what a speaker set out to do with the facts (Corbett 321). The penultimate part of arrangement, refutatio, or refutation of the facts, dealt with the opposite side of an argument; in this part, the presenter had to anticipate and to be prepared to defend an argument to the opposing side. The final part of arrangement, peroratio, or the conclusion, provided the closing of the argument. This final part of arrangement could be important because, according to Edward P. J. Corbett, “without a conclusion, the discourse strikes us as merely stopping rather than ending” (328). Put simply, an argument needed a proper ending by recapping the main points and providing one’s final thoughts on the subject. One fact must be kept in mind about arrangement in Ancient Greece, however: its use during this era was concerned with oral discourse and was used, according to Erika Lindemann, to enable “politicians, lawyers, and statesmen to argue court cases, shape political decisions about the nation’s future, or make speeches of praise or blame on ceremonial occasions” (41). Indeed, Corax first formulated arrangement as method that enabled effective argumentation in a 2 Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 court of law, which he, according Edward P. J. Corbett, “proposed for the parts of a judicial speech” (595). In another instance of the importance of arrangement, Corbett cites the case of Athenian orators Aeschines and Demosthenes. In an oratorical contest, Aeschines declared that Demosthenes’s speech conform to a certain arrangement pattern (Corbett 302). However, Demosthenes asked that he be allowed to use the form of arrangement of his choice, as that could determine the outcome of the contest (Corbett 302). As important as arrangement was to the early rhetoricians, it would encounter challenges in the years to follow. Turning Point As a concept, arrangement would encounter a serious challenge with the onset of the Renaissance. By this time, university students were routinely studying the trivium, a set of courses that consisted of three disciplines: grammar, logic, and rhetoric, what was considered a classic liberal education. It was believed that university students would benefit greatly from these courses in that they made the students better-prepared for argumentation. Indeed, the overall goal, according to Nedra Reynolds, Jay Dolmage, Patricia Bizzell, and Bruce Herzberg, was preparing “the beginning student for the serious business of the university. . .which offered practice in oral argumentation on historical, religious, or legal issues” (2). As important as university professors considered the trivium to educating students, however, Peter Ramus saw a need to make changes to this course of study. Ramus, a French rhetorician, set about reforming the trivium by separating the three subjects; in the process, he relegated arrangement to the realm of logic. His reason for this separation, according to Reynolds, Dolmage, Bizzell, and Herzberg, was to “define a logical scientific discourse. . .that would win assent from the rational audience by virtue of rationality alone” (2). In other words, Ramus believed arrangement to be antithetical to a discourse that, in his view, was increasingly in need of “nonlogical appeals” (Reynolds, 3 Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 Dolmage, Bizzell, Herzberg 2). As a result, arrangement was relegated to the margins of rhetoric and remained a relatively unimportant part of written discourse right up through the mid-20th century. At the beginning of the 1960s, however, composition specialists began looking to the classical texts, which contained the five-stage process (invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery) in an effort to revive writing as a process (Reynolds, Dolmage, Bizzell, Herzberg 6-7). Incidentally, arrangement “began to be reclaimed for composition studies as preliminary stages in the writing process” (Reynolds, Dolmage, Bizzell, Herzberg 7). In short, this second canon of classical rhetoric, first created as an effective method of discourse in Ancient Greece, was increasingly viewed in a different, more modern era as an important part of the writing process and a crucial component in composition studies. Into this revival of arrangement as part of the writing process came an organization model that changed the course of composition studies. Stephen Toulmin was a British educator and philosopher who outlined a multi-step model of argumentation, a model that closely resembled the models of arrangement that were first outlined by Corax, Tisias, and other rhetoricians centuries earlier. In his 1958 book, The Uses of Argument, Toulmin asserted that “we must ask what features a logically candid layout of arguments will need to have” (95). In other words, Toulmin believed that in order for an argument to be sound, it must be organized in a more nuanced, complex structure; to this end, he was critical of the simpler model of arrangement proposed by Aristotle. Indeed, Toulmin questioned “whether this standard form is sufficiently elaborate or candid” (96). To this end, Toulmin outlined a six-step model of argument: 1) data; 2) claim; 3) warrants; 4) qualifiers; 5) rebuttals; and 6) backing. As we will see shortly, in addition to its structure resembling the arrangement models of the early rhetoricians, his model placed extra importance on the proving of its data, claims, and warrants. 4 Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 In a sample of Toulmin’s argument model, the introduction serves as the beginning, during which the claim, or thesis, is first established. Toulmin’s model then moved on to the most important parts: the data, the warrants, and the backing, where the writer would then attempt to prove his/her argument. Toulmin began by describing the data. In his book, he described data as “the facts we appeal to as a foundation for the claim” (97). The data were, simply, the facts cited to initially support the original argument. However, data by themselves were not enough to prove a thesis. As Toulmin asserted, “We may now be required. . .to indicate the bearing on our conclusion of the data already produced” (98). To further prove the claims made by the data, Toulmin proposed the use of warrants. Warrants, Toulmin said, were “general, hypothetical statements, which can act as bridges, and authorise (sic) the sort of step to which our particular argument commits us” (98). A claim could be proven with a statement that would quell any disputes about its truth; in other words, assumed knowledge would prove the claim. Claims and warrants, however, still could not be sufficient to make one’s argument. Even if one believes he/she has constructed a sound argument, another person may still need further proof. In short, this person wants the rhetor to back up his/her claims. According to Toulmin, backing consisted of the “other assurances, without which the warrants themselves would possess neither authority nor currency” (103). These “other assurances” that Toulmin referred to were solid, well-known facts by which claims and warrants could be further proven. Toulmin’s model not only provided a structure for making sound arguments but also provided a model for written discourse that many composition studies classes have come to use. Arrangement Today Since the late 1950s, Stephen Toulmin’s method of organization has served as the model for modern written discourse and continues to be utilized in English composition classes today. 5 Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 However, the courses in which the model is taught have evolved, particularly in the increasing influence of ESL instruction. For example, Purdue University professor Irwin Weiser remarked on the increase in international students in English composition classes: “Over the past decade alone, the number of international students studying in the United States has increased by 40 percent” (Weiser 515). Weiser was referring to the number of Chinese students who had arrived in the United States in recent years. Additionally, he commented on the identification of and need for second-language instruction in the field of rhetoric and composition: “. . .scholars in rhetoric and composition, often with backgrounds in ESL, have identified a specific field of scholarship and research in second language learning” (Weiser 515). In a similar vein, Paul Kei Matsuda also acknowledges the need for ESL instruction in composition studies courses. He focuses particularly on the separation of ESL instruction from English composition and on the history that brought about this separation. However, while Matsuda does advocate the need for ESL instruction to help second-language learners in composition, he does not necessarily call for the merger of ESL and composition studies, since the two disciplines “have established their institutional identities and practices over the last three decades” (Matsuda 715). Instead, he believes that “second-language writing should be seen as an integral part of both composition studies and second-language studies” (Matsuda 715). To this end, he proposes the following solutions for English composition instructors: they should “ begin learning about ESL writing and writers by reading relevant literature and by attending presentations, workshops, and special interest (sic) meetings on ESL-related topics at professional conferences” (Matsuda 716). In addition, Matsuda suggests that “graduate programs in composition studies should also try to incorporate second-language learning. . .because graduate school is where institutional values are instilled in new members of the profession” (Matsuda 716). 6 Veronica Anzaldua ENG 6323.01 May 13, 2015 Conclusion Arrangement as a rhetorical concept has played an important role in both oral and written discourse. It has evolved from a model of spoken discourse designed to assist people in defending themselves to an organizational structure that facilitates the writing process in English composition courses. As new technologies and social trends come into being, arrangement will continue to evolve to become a richer, more diversified concept, while also continuing to fulfill its purpose of persuading and proving arguments. 7