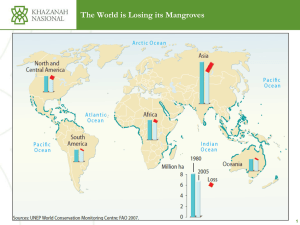

Corner Inlet Ramsar site: Ecological Character Description Chapter

advertisement