Erica Rangel paper 2014 - eCommons@Cornell

advertisement

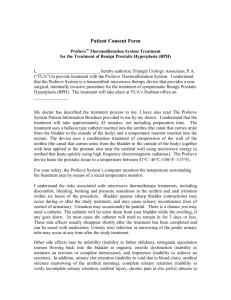

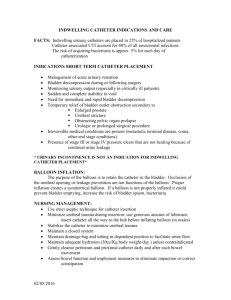

Urethral Stricture and Perineal Urethrostomy in a Ferret Erica Rangel Basic Science Advisor: Dr. Jamie Morrisey Clinical Advisor: Dr. Andrew Cushing Senior Seminar Paper Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine January 22, 2014 KEY WORDS: ferret, urinary, obstruction, urethra, stricture, perineal urethrostomy ABSTRACT: A 3.5-year-old male castrated ferret was initially seen at Cornell University Hospital for Animals (CUHA) for urethral obstruction due to cystine urolithiasis, which was surgically corrected with a cystotomy and urethrostomy. The ferret twice returned post-operatively for transient urinary obstruction at which times diagnostic testing ruled out urolithiasis and infection. The patient presented most recently for a 24-hour history of stranguria that could not be pharmacologically resolved. Physical examination revealed moderate abdominal distension and a painful, turgid, nonexpressable bladder. An abdominal ultrasound was highly suggestive of a perineal hernia with bladder prolapse. A cystopexy was performed and the urethra became patent, but by the following morning the patient had reobstructed. A repeat ultrasound confirmed an intact pexy site. A contrast cystogram revealed a severely dilitated pelvic urethra secondary to a penile urethral stricture. The patient was again taken to surgery for a microscope-aided perineal urethrostomy. Surgery was successful. INTRODUCTION: A 3.5-year-old male castrated ferret (Mustela putorious furo), originally presented to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals (CUHA) Emergency service on 9/15/2012 for stranguria and was acidotic, hyperkalemic and azotemic on presentation. The ferret was diagnosed with urinary obstruction secondary to cystine urolithiasis, which was surgically corrected with a cystotomy and urethrotomy. The patient was discharged with a guarded prognosis and high likelihood of reobstruction. The patient represented for additional episodes of urinary obstruction two and nine months post-operatively. On those visits, diagnostics revealed that the patient was negative for uroliths or urinary tract infection. The owners declined further diagnostic work up at these times, and a presumptive diagnosis of urethral stricture was made. The patient’s urethra became patent with urinary catheterization and conservative medical management. The ferret was maintained at home for six months with an oral treatment regimen to reduce inflammation (meloxicam 0.3 mg q24) and to encourage urethral atonicity (diazepam 0.25 mg q12 and prazosin 0.13 mg q12). Oral acepromazine (0.1 mg) was administered as a rescue sedative and antispasmodic. 2 The patient represented to CUHA Emergency 15 months after initial presentation after the owner noticed severe signs of intermittent stranguria for approximately 3 days. That evening the stranguria had progressed to anuria that was unresponsive to pharmacologic intervention. The ferret was otherwise healthy, with no other past pertinent medical history, and was eating and drinking normally according to the owners. PHYSICAL EXAM & STABILIZATION: Upon presentation, the patient was bright and alert, but uncomfortable. The vital parameters were all within normal limitsi (temperature 101.3 F, pulse 200 beats per minute, and respiration 32 breaths per minute). On physical exam, the abdomen was distended by a turgid, full bladder that could not be manually expressed. There was a questionable mass near the region of the left kidney on abdominal palpation and mild periodontal disease noted. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable. The patient was sedated (butorphanol 0.2 mg/kg IM and midazolam 0.5 mg/kg IM) so a urinary catheter could be placed. Urethral catheter placement is challenging in the male ferret due to the animal’s small size and J-shaped os penis. The urethral opening lies on the ventral aspect just proximal to the tip of the penis within the groove of the os penisii. Similar to a dog, the os penis can be used to help extrude the penis from the prepuce. A 3.5fr red rubber catheter was lubricated and easily passed in a sterile fashion yielding 40 ml of urine (normal daily urine output for a full bladder in ferrets is 26-28 ml) 2 . Urine was saved for diagnostic testing, and the catheter was removed due to financial constraints. A blood sample was obtained for point of care testing that was normal save a very mild anemia (PCV 40%, TS 6.2, AZO 16-26, and Glu 114 mg/dL). Buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg q6) as well as fluids (LRS 30 ml/kg q12) were administered subcutaneously. Maintenance fluid rates for ferrets have been based on those for cats at 50 to 70 mL/kg/diii. The patient ate well and rested comfortably throughout the night. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES: The top differential diagnoses for the patient’s urinary obstruction included urolithiasis, prostatomegaly, and urethral stricture. Lower on the differential list was neoplasia, ruled down by the patient’s age, and an upper motor neuron bladder secondary to a neuropathy, ruled down by a lack of any other clinical 3 signs. Urolithiasis is the most common cause of urinary obstruction in ferrets and the patient had a history of this disease. In male ferrets, the second most common cause of urinary obstruction is compression of the urethra secondary to cystic prostatomegaly resultant from chronic androgen stimulation secondary to adrenal diseaseiv, v. DIAGNOSTIC FINDINGS: The morning following presentation, the patient was again painful and anuric, posturing so frequently that tenesmus and secondary loose stool accompanied. The patient was maintained on buprenorphine at 0.02 mg/kg SQ q8 and diazepam up to 0.2 mg PO q12. The ferret was sedated and an abdominal ultrasound was performed. Visualization of the urinary bladder revealed a normal thickness and echogenicity of the wall, and was negative for masses, stones, or sediment. A portion of the bladder was found caudal to the pelvis and was very dilated. The precise cause of lower urinary obstruction was not determined but might be occurring in the urethra downstream from the ischial arch or might be associated with caudally displaced urinary bladder with abnormal narrow region or substantially dilated prostatic and pelvic urethra and patent cystourethral junction. Ureteral jets were not found by color flow Doppler, so the trigone of the bladder could not be identified. The extreme dilatation of the caudally displaced bladder (approximately two times larger than the normally positioned cranial bladder) pointed to a perineal hernia with bladder prolapse as the new top differential diagnosis, however other causes like malformation, stricture, neuromuscular problems, or dilation secondary to downstream urethral obstruction could not be ruled out. Additional ultrasonographic findings included: moderate generalized splenomegaly of nonspecific pathogenesis (hyperplasia, extramedullary hematopoiesis, inflammation, diffuse neoplasia); possible bilateral mild adrenomegaly; and a minuscule amount of peritoneal fluid likely secondary to inflammation. The prostate was imaged to be normal. Therefore, despite adrenomegaly (likely correlating with the mass felt near the region of the left kidney o abdominal palpation) possibly pointing to early adrenocortical disease, that was not the cause of the urinary obstruction Following ultrasound, another 3.5Fr red-rubber catheter was passed. A sample of urine was obtained for urinalysis and sediment exam testing. This time the patient was fitted with an indwelling catheter and closed urine collection system. Once the catheter is 4 in place, butterfly tape strips were used to suture the catheter to the skin in the ventral abdomen in multiple locations. The catheter was then taped to the base of the tail to reduce tension at the sutured areas. A closed urinary collection device was created from a sterile fluid drip set and empty fluid bag3, 4, vi. Lastly a full body wrap consisting of an orthopedic tube stocking with openings for arms and legs reinforced with 2” Elasticon was fashioned. The ferret had a history of chewing out his urinary catheters, which was not only time consuming and costly to replace, but served as a source of potential foreign body if ingested. Urinalysis results were unremarkable. The sediment was negative for crystals, casts, bacteria or white blood cells ruling out stones or infection as the source of urinary obstruction. The increased red blood cells (20-100 phpf) and epithelial cells (many) were consistent with repeated catheterization experienced by the patient TREATMENT: Based on the high index of suspicion of perineal hernia, the soft tissue surgery service was consulted. While a perineal hernia had never been described in the literature, clinical signs of intermittent urinary obstruction experienced by the patient could be attributed to the bladder getting periodically entrapped in the hernia. This has been described in cats and dogs with perineal hernia. The patient was taken to surgery for a cytopexy to replace and secure the bladder cranially and prevent further herniation and subsequent obstruction. The patient was induced under general anesthesia and monitored in a standard fashion. Cystopexy: A standard ventral midline celiotomy was performed. Once inside the abdomen the bladder was located and pulled cranially. The bladder was emptied via external syringe from the urinary catheter. A stay suture with 4-0 PDS was placed at the apex of the bladder. An approximately 1 cm diameter area of the right body wall in line with the cranial fist third of the incision, and a similar sized area of the right dorsal base of the bladder were excoriated with a scalpel blade. Three tags of suture were placed connecting the body wall to the bladder (serosa and muscularis layers) then they were cinched down and secured with a surgeons knot in a cranial to caudal fashion. The bladder stay suture was removed. The body wall and muscularis was closed with 4-0 PDS in a simple continuous pattern, and the skin was closed in an intradermal pattern. The 5 urinary catheter was removed, the urethra was patent on manual expression of the bladder, and the patient recovered from anesthesia without complicationvii. The patient was started on anti-inflammatories and antibiotics postoperatively in addition to continued analgesics (buprenorphine 0.02 mg/kg SQ q8, meloxicam 0.2 mg/kg SQ q24, ampicillian sublactam 22 mg/kg SQ q8, diazepam PRN). The morning after surgery the patient was dehydrated, painful and again exhibiting signs of stranguria and tenesmus. A suspected reherniation was ruled out by a repeat abdominal ultrasound which showed an intact pexy site characterized by traditional tenting of the rectus abdominus muscle and visible suture loops. The patient was relieved of urine with an emergency cystocentesis (yielding 44 ml). After consulting the owner, additional diagnostics were elected in order to revise the diagnosis. Contrast Cystography: The patient was again sedated and a catheter was placed in the urinary bladder prior to this study. With the patient in right lateral position, contrast material (10 ml iohexol-350) was injected into the catheter as the catheter was retracted. The patient was then examined in dorsal recumbency. With the patient again in right lateral, the urinary bladder was manually compressed. Upon manual expression, a urethral stricture was appreciated just proximal to the start of the os penis, as determined by a lack of contrast media in the penile urethra and subsequent extreme dilatation of the pelvic urethra. Additionally, a small rent in the pelvic urethral was seen, likely secondary to the previous “cystocenesis” which in actuality was a urethrocentesis. DEFINITIVE DIAGNOSIS: Penile urethral stricture with severely dilitated pelvic urethra and iatrogenic pelvic urethral tear. Due to the fragility of the urethra and in an effort to prepare the patient for another surgery, the ferret was outfitted with another indwelling urinary catheter and was hospitalized with supportive care for the next 48 hours. The day of surgery, the patient was induced under general anesthesia, a jugular catheter was placed and he was monitored in a standard fashion. Perineal Urethrostomy: The patient was placed in dorsal recumbency and prepped using standard aseptic technique. A 1-2cm incision was made on midline over the prescrotal region using a micro blade. Blunt dissection of the subcutaneous tissues 6 was performed to allow visualization of the penis retractor muscle and the urethra. Hemorrhage was controlled by electrocautery. The location of the urethra was confirmed by palpation of a previously placed indwelling the urinary catheter (red rubber). A fresh micro blade was used to incise the urethra, making an approximately 1cm incision parallel to the skin incision. The urethral mucosa and the skin were opposed and sutured in a simple continuous pattern using 6-0 PDS. Two lines of suture were used, one on either side of the urethrostomy. Two simple interrupted sutures were placed at the very cranial and caudal ends of the urethrostomy site. Additionally, two simple interrupted sutures were placed on the right edge of the site to improve skin-to-mucosa apposition. A catheter could easily be passed through the stoma proximally and distally. The urinary catheter was removed and patency of the site was ensured by palpating and expressing the bladder and visualizing urine coming out of the stomaviii, ix. OUTCOME: The surgery was a success and only a mild urinary incontinence was noted. The patient was monitored in the intensive care unit for 24 hours with supportive care of intravenous fluids (Lactated Ringers Solution at 3ml/hr), buprenophine, meloxicam, and ampicillin sublactam. The jugular catheter was removed and the patient was transitioned to oral medications once eating and drinking well. He was discharged to the care of his owners 5 days after initial presentation and sent home on the following medications: meloxicam (0.2 ml PO SID x4 days), diazepam (0.1-0.2 ml q12 PRN), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxine (15 mg/kg q12 PO x10 days), and tramadol (5 mg/kg 0.35 ml PO q12-24 PRN x7 days). The patient continued to do well at home postoperatively after being weaned off all his medications. Two weeks following discharge and the owner reported that all urinary incontinence had resolved, there had been no episodes of stranguria, and his energy level was improved. The patient was to return for a recheck and suture removal a week later. DISCUSSION: Cystine stones are rare in ferrets accounting for only 16% of uroliths submitted for analysis. According to the Minnesota Urolith Center, out of 435 uroliths (1992-2009), struvite was the most common at 67%. The etiology of cystine urolithiasis 7 in ferrets is currently unknown, though anecdotal reports have linked it with nutrition, particularly ferrets eating a cat-food only diet. A familial pattern of inheritance has not been reported in ferrets, but genetic factors associated with the disease have been determined in humans and certain dog breeds impairing the renal proximal tubules ability to reabsorb cystinex. Adrenocortical disease is the second most common endocrinopathy in domestic ferrets (after insulinoma) with an estimate of 70% of the US pet ferret population affected in 2003. It has no sex predilection and affects mainly middle-aged ferrets with a mean age of onset of 4 years old.xi The high incidence is likely due to a genetic bottleneck from a small founder population. Unlike Cushing’s Disease of dogs and cats, ferret adrenal disease affects the zona reticularis and thus results in a hyperandrogenism marked by increases in sex hormones. The clinical signs, and subsequent diagnosis of ferret adrenal disease, are largely a result of increased sex hormones. Retrospective analysis has shown that the most common presenting complaints include progressive alopecia (>90%) with accompanying pruritis (40%), vulvar swelling (>70% of females) and cystic prostatic enlargement in males—which may lead to emergency urinary obstruction, stranguria, or tenesmus. Other clinical signs include mammary gland enlargement (both sexes), muscle wasting, lethargy, aggression, and increased odor.7 In one study, estrogen was elevated in 36% of cases, 7-hydoxyprogesterone was elevated in 60% of cases, and androstendione was elevated n 76% of cases. 96% of ferrets with adrenocortical disease had an elevation in at least one of the aforementioned hormones, and 22% showed an elevation in all three. xiiA ferret sex steroid serum panel is available through the University of Tennessee that validates increases in sex hormones (estrogen, 7-hydoxyprogesterone and androstendione).xiii In male ferrets, an increase in one hormone is diagnostic. In female ferrets, an increase in estrogen alone must be differentiated from other possible sources including persistent ovarian remnant, but an increase in two or more is considered diagnostic. The patient ultimately had surgical success and the urinary obstruction was relieved. However, one can not help to comment on the fact that if all imaging diagnostics had been pursued prior to surgery, the patient could have been spared an 8 unneccesary surgical procedure. While perineal hernia seemed likely based on ultrasonographic evidence, it was a novel diagnosis not originally on the list of differentials, and urethral stricture should have been ruled out first. REFERENCES: Wolf, TM. (2009). Ferrets. In: Manual of Exotic Pet Practice. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 345-74. i Brown C & Polluck C. (2011).Urethral Catheterization of the Male Ferret for Treatment of Urinary Tract Obstruction. Lab Animal Medicine 40 (1): 19-20. ii Castanheira deMatos, RE & Morrisey, JK. (2006). Common Procedures in the Pet Ferret. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 9 (2): 346-65. iii Orcutt, CJ. (2003). Ferret Urogenital Diseases. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 6 (1): 113-38. iv Fisher, PG. (2006). Exotic Mammal Renal Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 9 (1): 69-96. v Pollock, C. (2007). Emergency Medicine of the Ferret. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 10 (2): 463-500. vi Mullen, HS & Beeber, NL. (2000). Miscellaneous Surgeries in Ferrets. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 3 (3): 663-71. vii viii Bartlett, LW. (2002). Ferret Soft Tissue Surgery. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine.11 (4): 221-230 Lightfoot, T et al. (2012). Soft Tissue Surgery. In: Ferrets, Rabbits and Rodents, Clinical Medicine and Surgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 141-56. ix x Nwaokone EE et al. (2013). Epidemiological Evaluation of Cystine Urolithiasis in Domestic Ferrets (Mustela putorius furo): Seventy Cases (1992-2009). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 242 (8): 1099-103. Simone-Freilicher E. (2008). Adrenal Gland Disease in Ferrets. Vet Clin Exot Anim 11: 125-137 xii Rosenthal KL, Peterson ME. (1996). Evaluation of Plasma Androgen and Estrogen Concentrations in Ferrets with Hyperadrenocorticism. J Am Vet Med Assoc 209:10971102. xi 9 The University of Tennesse Clinical Endrocrinology Service website. Date accessed: 2/15/2014. http://www.vet.utk.edu/diagnostic/endocrinology/ xiii 10