Sidewalks - Georgetown University Law Center

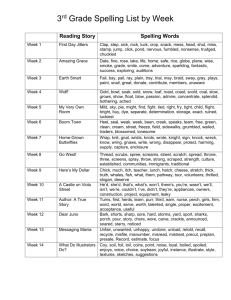

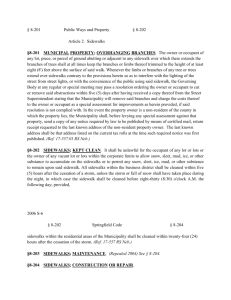

advertisement

As you can see, the sewer installation has ended along 2nd Street, and BBC contractors are laying a temporary sidewalk. When they are done, the fences will be moved to the curb line so we will have unimpeded, albeit with a slight deviation in front of McDonough, pedestrian access between E Street and Massachusetts Avenue. It should only take a few days to complete the job. We take so much for granted as we walk about our modern cities. Wide boulevards, pocket parks and urban forests, historic facades and iconic modern buildings all surround us, but they seldom get a second look as we hurry about our business. Sidewalks and streets are practically invisible to our consciousness unless we stumble on some broken paver. Sidewalks especially, are undervalued urban forms. It seems that their only obvious purpose is to connect the dots as we move about our busy lives. Although we usually take them for granted, sidewalks can reveal wonders to the patient eye. Sidewalks delight and excite. They are the haunts of the flâneur -- places where classes, genders, and ages mix openly and freely, sometimes together and sometimes with complete anonymity. They are places where we fall in love and places where hearts are broken. Sidewalks are places where political opinions are offered, sometimes peacefully but sometimes with violence. They are places of grand parades and ceremony, yet they sometimes seem sinister as night falls and lights grow dim. Sidewalks can be the stuff of imagination. French Impressionists found Paris sidewalks exquisite, fit subjects for oil and canvas. Childe Hassan was equally enamored of the sidewalks of New York. Movies bear titles like “Sidewalks of London,” “Sidewalks of New York,” and “Sidewalk Stories.” We sing songs about sidewalks and the lives played out upon them. Novelists like Charles Dickens, Theodore Dreiser, Victor Hugo, and many others find urban sidewalks inescapable arenas for revealing life’s joys and sorrows, and poets cannot seem to get enough of them. As Marcus Young, St. Paul City Artist in Residence since 2006 once said, “Sidewalks are the blank pages of our city as a book.” And as I have recently discovered, there are even whole books devoted to the art and science of sidewalks. Of course, it was not always this way. Sidewalks, that is, paved walkways that are next to but separated from a main road, first appeared at the Karum of Kultepe, a merchant quarter in an ⌂ Sidewalks in the Karum of Kultepe ⌂ ⌂ Roman sidewalks in Pompeii ancient city in what is now Turkey around 2000 BCE, and at Corinth in ancient Greece in the 4th century CE. The Romans had sidewalks in many cities as early as the third century BCE, but their roads and sidewalks fell into disuse as the Roman Empire crumbled. After the Roman Empire disappeared, medieval European citizens walked in roads without sidewalks. Sidewalks reappeared in London only after the Great Fire of 1666, and became more common in the 18th century in both Paris and London. By the late 19th century, sidewalks began to appear in Vienna and Barcelona and in most other large European cities. Major U.S. cities followed suit and by the early half of the 19th century, large American cities had curbs and sidewalks along their most heavily traveled streets. As with many urban improvements, Washington was late to the game. Before 1806 only F Street and a few other thoroughfares were paved. Sidewalks existed on F Street but they were paid for with individual subscriptions by the residents. Walkways are visible in old engravings of D.C. but many of them, especially on secondary streets, were made of wood. By the time of the Civil War, however, at least Pennsylvania Avenue was shaping up to be a fashionable boulevard with a wide sidewalk and a curb to separ- Pennsylvania Avenue and 7th Street in 1839. Pennsylvania Avenue at 6th Street in 1860. ate it from the street. Urban amenities improved after the Civil War and, as with most public works in Washington, Boss Shepherd led the way. Shepherd was determined to build streets and sidewalks between the Mall and P Street to the north and between New Jersey Avenue on the east to New Hampshire Avenue on the west. Constance McLaughlin Green quotes a resident as saying that it was “a daily occurrence for citizens to leave their houses as usual in the morning, and when they returned at the evening, to find sidewalks and curbs.” Shepherd was building for the future so it did not matter that many of the blocks had no buildings. The raised curb and sidewalk became more common in Europe with the introduction of macadam paving. Macadam paving, named after Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam, developed around 1820. He used aggregated layers of single-sized small stones to produce a road that solidified as traffic passed over its surface and compacted the stones together. The angles of the crushed stone alone created a solid lasting structure. Shepherd preferred asphalt and wood for roads and sidewalks in D.C. even though macadam was cheaper. The first macadam surface in the United States was laid on the "Boonsborough Turnpike Road" between Hagerstown and Boonsboro, Maryland around 1822. The second, in the 1830s, was the National Pike, sometimes called the Cumberland Road and now designated as U.S. Route 40. It connected the Potomac and Ohio rivers and became the major road for settlers moving west. McAdam’s method was later enhanced when engineers added water and dust to A macadam road in 1850 better bind the stones. Sometime later, engineers sprayed tar over the crushed stone surface to make the binding even better. Although newer road-surfacing methods eclipsed the various macadam methods, asphalt roads are still called macadam roads in some parts of the country, and we still use the term “tarmac” to describe airport runways. BBC Construction will be setting a temporary asphalt sidewalk this week because it makes little sense to use concrete pavers until the work on 2nd Street itself is completed. Asphalt, known in some places as bitumen, is a sticky, black, and highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It was known to the ancients who used it for various purposes, and it is even mentioned in the Bible. When a macadam surface was laid, the stone and sand aggregates were placed on the road first and the water or tar binding material was sprayed over it. Unlike the various macadam methods, BBC workers will mix the asphalt and the aggregates together before they pave the sidewalk. Sidewalks, like sewers and other underappreciated aspects of urban living, have their own histories filled with colorful inventors and even more colorful stories. There is so much to explore and reveal. Perhaps I will say some more about them when the permanent sidewalk is installed. In the meantime, take some time out of your busy day to pause and appreciate the familiar, and to find joy in the everyday surroundings of Pierre L’Enfant’s magnificent city. For today, I leave you with this. Where the Sidewalk Ends by Shel Silverstein There is a place where the sidewalk ends And before the street begins, And there the grass grows soft and white, And there the sun burns crimson bright, And there the moon-bird rests from his flight To cool in the peppermint wind. Let us leave this place where the smoke blows black And the dark street winds and bends. Past the pits where the asphalt flowers grow We shall walk with a walk that is measured and slow, And watch where the chalk-white arrows go To the place where the sidewalk ends. Yes we'll walk with a walk that is measured and slow, And we'll go where the chalk-white arrows go, For the children, they mark, and the children, they know The place where the sidewalk ends. Sources Loukaltou-Sidaris and Ehrenfeucht, SIDEWALKS, (MIT Press 2009) Constance McLaughlin Green, WASHINGTON: A HISTORY OF THE CAPITAL, 1800-1950 (Princeton University Press 1976). http://publicartstpaul.org/poetry/ http://famouspoetsandpoems.com/poets/shel_silverstein/poems/14836 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%BCltepe http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macadam http://curbstone.com/_macadam.htm