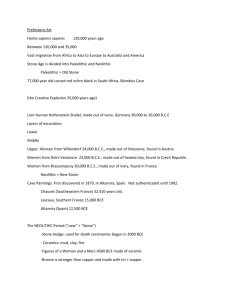

notes for part 2

advertisement

1. Title 2. Second title 3. Prehistoric artists carved and modeled sculptures in a variety of materials. At just under a foot high, a carved figure from Hohlenstein- Stadel in Germany represents a standing creature, half human and half feline, crafted out of mammoth ivory. now in a poor state of preservation Created with rudimentary stone tools involved splitting the dried mammoth tusk scraping it into shape, and using a sharp flint blade to incise such features as the striations on the arm and the muzzle. Strenuous polishing followed, using powdered hematite ( an iron ore) as an abrasive. Exactly what the figure represents is unclear. 4. Artist: n/a Title: Lion-Human Medium: Mammoth ivory Size: height 11⅝" (29.6 cm) Date: c. 30,000–26,000 BCE Source/Museum: Hohlenstein-Stadel, Germany / Ulmer Museum, Ulm, Germany Some have interpreted it as half woman, half lion, based on the fact that Upper Paleolithic sculpture is primarily of animals or nude women. Taller than most figures from the period Unusual combination of human and animal elements- could be an imagined creature. Could represent a costumed human participating in a ritual, although we know nothing about what those rituals might have entailed. Since unsexed figures are not uncommon, it is impossible to say with certainty that the Lion-Human represents anything more specific than a combined human and animal form. 5. Title: Woman from Willendorf Medium: Limestone Size: height 4⅜" (11 cm) Date: c. 24,000 BCE Source/Museum: Austria. Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna Women were frequent subjects in prehistoric sculpture. In fact, so far do female images outnumber male images at that time that they may be evidence of a matrilineal social structure. hand- sized, limestone carving of the nude Woman of Willendorf of Austria, from about 28,000 to 25,000 bce. Discovered in 1908, her figure still bears traces of ocher rubbed onto the carved surface. highly abstract. 6) Other examples of female figures found in various locations tend to support the notion of an Upper Paleolithic period “style” or at least a common perception of form and a shared technique and skill level. The abstract quality of the Woman of Willendorf appears to stress a potent fertility. This kind of abstraction appears in many other figurines as well; indeed, some incomplete figurines depict only female genitalia. Facial features are not a priority: schematically rendered hair covers the entire head. Emphasis rests on the figure’s reproductive qualities: Diminutive arms sit on pendulous breasts, whose rounded forms are echoed in the extended belly and copious buttocks. Genitalia are shown between large thighs. • • • • • Does the Woman of Willendorf represent a specific woman, or a generic or ideal woman? may not represent the idea of woman at all, but rather the notion of reproduction the fertile natural world itself. The emphasis on the reproductive features has suggested to many that she may have been a fertility object; the intention may have been to ensure a successful birth outcome rather than an increase in the number of pregnancies. According to one feminist view, the apparently distorted forms of figures like this specifically reflect a woman’s view of her own body as she looked down at it. If so, some of the figures may have served as obstetric aids, documenting different stages of pregnancy to educate women toward healthy births. Moreover, this may indicate that at least some of the artists were women. 7) Title: Woman from Brassempouy Medium: Ivory Size: height 1¼ (3.6 cm) Date: Probably c 30,000 BCE Source/Museum: Grotte du Pape, Brassempouy, Landes, France. Musée des Antiquités Nationales, St-Germain-en-Laye, France In the late nineteenth century, a group of 12 ivory figurines were found together in the Grotte du Pape at Brassempouy in southern France. Among them was the Woman from Brassempouy of about 22,000 bce. The sculpture is almost complete, depicting a head and long elegant neck. At a mere 11/ 2 inches long, it rests comfortably in the hand, where it may have been most commonly viewed. Also highly abstract; reduced it to basic shapes. The artist rendered the hair schematically with deep vertical gouges and shallow horizontal cross- lines. There is no mouth and only the suggestion of a nose; hollowed- out, over-hanging eye sockets and holes cut on either side of the bridge of the nose evoke eyes. The quiet power and energy of the figure reside in the dramatic way its meticulously polished surface responds to shifting light, suggesting movement and life. 8) Memory image abstract 9) 24,000, 23,000, 30,000 BCE (dates of each artifact from left to right) 10) Around 10,000 bce, the climate began to warm, and the ice that had covered almost a third of the globe started to recede, leaving Europe with more or less the geography it has today. New vegetation and changing animal populations caused human habits to mutate, especially in relation to their environment. In the Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, they began to build more substantial structures, choosing fixed settlement places on the basis of favorable qualities such as a water supply, rather than moving seasonally. Instead of hunting and gathering what nature supplied, they domesticated animals and plants. This gradual change occurred at different moments across the world; in some places, hunting and gathering are still the way of life today. 11) Seated Man and Woman, Cernavoda, Romania. Ceramic, 4 ½inches. C.3,500 BCE Size: height 4½" (11.5 cm) Date: c. 3500 BCE Source/Museum: Cernavoda, Romania; National Historical Museum, Bucharest NEOLITHIC CERAMIC SHOWS A HIGH LEVEL OF SKILL In Europe, artists also used clay to fashion figurines, such as a woman and man from Cernavoda in Romania, of about 3500 bce ( fig. 1.22). Like the Woman of Willendorf, they are highly abstract, yet their forms are more linear than rounded: The woman’s face is a flattened oval poised on a long, thick neck, and sharp edges articulate her corporeality— across her breasts, for instance, and at the fold of her pelvis. Elbowless arms meet where her hands rest on her raised knee, delineating a triangle and enclosing space within the sculptural form. This emphasizes the figurine’s three- dimensionality, encouraging a viewer to look at it from several angles, moving around it or shifting it in the hand. The abstraction highlights the pose; yet, tempting as it may be to interpret this, perhaps as coquettishness, we should be cautious about reading meaning into it, since gestures can have dramatically different meanings from one culture to another. Found in a tomb, the couple may represent the deceased, or mourners; perhaps they were gifts that had a separate purpose before burial. 12) Title: Vessels Medium: Ceramic Size: heights range 5¾" to 12¼" (14.5 to 31 cm) Date: c. 3000–2000 BCE Source/Museum: Denmark. National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen from 5 3/4” to 12 1/4” Ceramic vessels were modeled after woven baskets Surfaces were decorated by scratching the surface with various sharp implements. Decorative patterns imitate the texture of weaving. White chalk sometimes rubbed into engraved lines to make them stand out against the dark body of the vessel. 13) title bronze age Neolithic culture persisted in northern Europe until about 2300– 2000 BCE. Metals had made their appearance about 2300 BCE, although gold and copper had been used in southern Europe and the Near East much earlier. The period that follows the introduction of metalworking is commonly called the Bronze Age. By 1000 BCE, iron technology had spread across Europe, although bronze remained the preferred material for luxury goods. Cheaper and more readily available than other metals, iron was most commonly used for practical items. The blacksmiths who forged the warriors’ swords and the farmers’ plowshares held a privileged position among artisans, for they practiced a craft that seemed akin to magic as they transformed iron by heat and hammer work into tools. A hierarchy of metals emerged based on each material’s resistance to corrosion: Gold, the most permanent and precious metal, ranked first, followed by silver, bronze, and finally practical but rust- prone iron. 14) Title: Horse and Sun Chariot Medium: Bronze Size: length 23¼" (59.2 cm) Date: c. 1800–1600 BCE Source/Museum: Trundholm, Denmark . National Museum, Copenhagen Dated to the early Bronze Age on the basis of stylistic elements, the horse is hollow-cast and is one of the earliest representations of a horse in Europe. The sun is made of two disks, ornamented with intricate decorations in concentric circles. This is a small-scale model of a vehicle that was presumably used for ceremonial purposes. Fullsize artifacts of similar vehicles have been found. Other evidence from Northern Europe (rock engravings showing the sun drawn across the sky by animals or birds) supports the hypothesis that this represents a horse pulling the sun. A sun cult could have been present in the region given that later Norse mythology (13th century) includes the story of a goddess Sunna (the Sun) who rides her chariot, pulled by horses, across the sky every day. The valuable materials from which the sculpture was made attest to its importance. The horse, cart, and disk were cast in bronze and delicately engraved with an abstract design of concentric rings, zigzags, circles, spirals, and loops. A thin sheet of beaten gold was then applied to the bronze disk and pressed into the incised patterns. The continuous and curvilinear patterns suggest the movement of the sun itself. 15) belt buckle 16) Title: Openwork box lid Medium: Bronze Size: diameter 3" (7.5 cm) Date: La Tène period, c. 1st century BCE protohistoric Source/Museum: Cornalaragh County Monaghan, Ireland / National Museum of Ireland, Dublin 17) title Paleolithic architecture 18) Title: Reconstruction drawing of mammoth-bone houses Date: c. 16,000–10,000 BCE Source/Museum: Ukraine In the Paleolithic period, people generally built small huts and used caves for shelter and ritual purposes. In rare cases, traces of dwellings survive. At Mezhirich, in the Ukraine, a local farmer discovered a series of oval dwellings with central hearths, dating to between 16,000 and 10,000 bce. The distinctive feature of these huts was that they were constructed out of mammoth bones: interlocked pelvis bones, jawbones and shoulder blades provided a framework, and tusks were set across the top. The inhabitants probably covered the frame with animal hides. Archaeological evidence shows that inside these huts they prepared foods, manufactured tools, and processed skins. Since these are cold- weather occupations, archaeologists conclude that the structures were seasonal residences for mobile groups, who returned to them for months at a time over the course of several years. 19) Use of curved mammoth tusks for roof supports and door opening shows not only creativity but also a sophisticated understanding of the properties of the materials used. The ability to re-create the design indicates a technological advancement that can be called “architecture”. 20) title megalithic architecture 21) elements of architecture 22) post/lintel & corbel 23) Title: Plan, village of Skara Brae (Numbers refer to individual houses) Medium: n/a Size: n/a Date: c. 3100–2600 BCE Source/Museum: Orkney Islands, Scotland Around 10,000 bce, the climate began to warm, and the ice that had covered almost a third of the globe started to recede, leaving Europe with more or less the geography it has today. New vegetation and changing animal populations caused human habits to mutate, especially in relation to their environment. In the Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, they began to build more substantial structures, choosing fixed settlement places on the basis of favorable qualities such as a water supply, rather than moving seasonally. Instead of hunting and gathering what nature supplied, they domesticated animals and plants. This gradual change occurred at different moments across the world; in some places, hunting and gathering are still the way of life today. 24) Title: House interior, Skara Brae Medium: n/a Size: n/a Date: n/a Source/Museum: Orkney Islands, Scotland Neolithic people of western and northern Europe framed their dwellings mostly in wood, with walls of wattle ( branches woven into a frame) and daub ( mud or earth dried around the wattle) and roofs of thatch, which rarely survive. At Skara Brae, on the island of Orkney just off the northern tip of Scotland, is a group of ten houses built of stone, dating to between 3100 and 2600 bce. The builders sunk them into mounds for protection against the harsh weather, and connected them by covered passages. A typical house had a square room, with walls of flat unmortared stones. Driftwood and whalebone supported a roof of turf thatch. At the center of the room was a hearth for cooking, and the inhabitants built furniture— such as beds and shelving— out of large flat stones. 25) Ceremonial Tomb It was a concern for ceremonial burial and ritual, rather than for protection, that inspired Neolithic people of western and northern Europe to create monumental architecture. They defined spaces for tombs and rituals with huge blocks of stone known as megaliths. Often they mounted the blocks in a trilithic (three- stone) post- and- lintel arrangement ( with two upright stones supporting a third horizontal capstone) to construct tombs for the dead with one or more chambers. 26) other example of post and lintel 27) New Grange 28) Title: Tomb interior with corbeling and engraved stones. Some stones are marked with linear designed rings, spirals, diamond shapes Date: c. 3000–2500 BCE Source/Museum: New Grange, Ireland At Newgrange in Ireland a huge passage grave was constructed about 3000– 2500 BCE. Rings, spirals, diamond shapes, and other linear designs were engraved on the stones at its entrance, around the base of the cairn, and along its entrance passageway. 29) Some stones are marked with linear designed rings, spirals, diamond shapes These patterns may have been marked out using strings or compasses, and then carved by pecking at the rock surface with tools made of antlers and hard stones. A cairn that measured about 280 feet in diameter and 44 feet tall concealed a chamber with alcoves and a corbel vault rising to a height of 19 feet. The ritual purpose of Newgrange is still a mystery; however, some powerful solar symbolism must have played a part. The builders oriented the passage to the rising sun in midsummer, at which time light enters through a semiconcealed opening down the length of the passage to the tomb chamber and falls on a shallow, scooped- out, platter- like stone. 30) TITLE SLIDE STONEHENGE Often, megaliths appear in circles, known as cromlechs. This is the prevalent arrangement in Britain, where the best- known megalithic structure is Stonehenge, on the Salisbury Plain . Excavations since 2002, however, have pointed to another possible significance for this and another nearby Neolithic site. While Stonehenge and its environs have emerged as the most extensive known Neolithic cemetery in England, with as many as 240 discovered graves, concurrent excavations at the nearby, and much larger, Woodhenge at Durrington Walls revealed remains of a thriving community of about 300 wooden houses, the largest- known Neolithic settlement in Britain. Archaeologists have suggested that these two contemporary sites could have been linked, one where people lived and the other where the most important among them were buried, both connected to the nearby Avon river by broad pro-cessional avenues. But even more recently, in 2008, excavations within the circle at Stonehenge itself demonstrated that the first ring of bluestones was added to the site between 2400 and 2200 BCE, much later than between 2400 and 2200 BCE, much later than archaeologists had previously believed. The theory emerging from this discovery holds that Stonehenge was at this time a healing center— a sort of prehistoric Lourdes. People from as far away as the Alps in mainland Europe made pilgrimages here, seeking relief from the effects of disease and injury by using water that had taken on therapeutic powers from the same bluestones that had been imported as construction material from a healing spring in Wales. 31) Exactly what Stonehenge signified to those who constructed them is a tantalizing mystery. Many prehistorians believe that Stonehenge marked the passing of time. Given its monumentality, most also concur that it had a ritual function, perhaps associated with burial; Its careful circular arrangement supports this conjecture, as circles are central to rituals in many societies. Indeed, these two qualities led medieval observers to believe that King Arthur’s magician, Merlin, created Stonehenge, and it continues to draw crowds on summer solstices. What is certain is that Stonehenge represents tremendous organization of labor and engineering skill. 32) What now appears as a unified design is in fact the result of at least four construction phases, beginning with a huge ditch defining a circle some 330 feet in diameter in the white chalk ground (it is believed that the ditch was dug with tools made from the antlers of red deer and, possibly, wood) and an embankment of over 6 feet running around the inside. A wide stone- lined avenue led from the circle to a pointed gray sandstone ( sarsen) megalith, known today as the Heel Stone. By about 2100 bce, Stonehenge had grown into a horseshoe- shaped arrangement of five sarsen triliths, encircled by a ring of upright blocks capped with a lintel; between the rings was a circle of smaller bluestone blocks. Recent excavations exposed remains of a similar monument built of wood 2 miles ( 3 km) away, as well as remnants of a village. Archaeologists believe the structures are related. 33) The largest trilith, at the center of the horseshoe, soars 24 feet, supporting a lintel 15 feet long and 3 feet thick. The lintels are worked in two directions, their faces inclining outward by about 6 inches to appear vertical from the ground, while at the same time they curve around on the horizontal plane to make a smooth circle. Art historians usually associate this kind of refinement with the Parthenon of Classical Athens ( see fig. 5.40). 34) The Bluestones About 2,000 BC, the first stone circle (which is now the inner circle), comprised of small bluestones, was set up, but abandoned before completion. The stones used in that first circle are believed to be from the Prescelly Mountains, located roughly 240 miles away, at the southwestern tip of Wales. The bluestones weigh up to 4 tons each and about 80 stones were used, in all. 35) Construction of the Outer Ring The sarsen blocks weigh up to 50 tons apiece, and traveled 23 miles ( 37 km) from the Marlborough Downs. To transport them from the Marlborough Downs, roughly 20 miles to the north, is a problem of even greater magnitude than that of moving the bluestones. Most of the way, the going is relatively easy, but at the steepest part of the route, at Redhorn Hill, modern work studies estimate that at least 600 men would have been needed just to get each stone past this obstacle 36) The blocks reveal evidence of meticulous stone working. Holes hollowed out of the capstones fit snugly over projections on the uprights ( forming a mortise- and- tenon joint), to make a stable structure. Moreover, upright megaliths taper upward, with a central bulge, visually implying the weight they bear, and capturing an energy that gives life to the stones. 37) Prehistoric art raises many questions. While we know humans began to express themselves visually during the prehistoric age, there are no written records to explain their intentions. Even so, by the end of the era, people had established techniques of painting, sculpting, and pottery making, and begun to construct monumental works of architecture. They developed a strong sense of the power of images and spaces: They recognized how to produce naturalistic and abstract figures, and how to alter space in sophisticated ways.