Henry Clay

advertisement

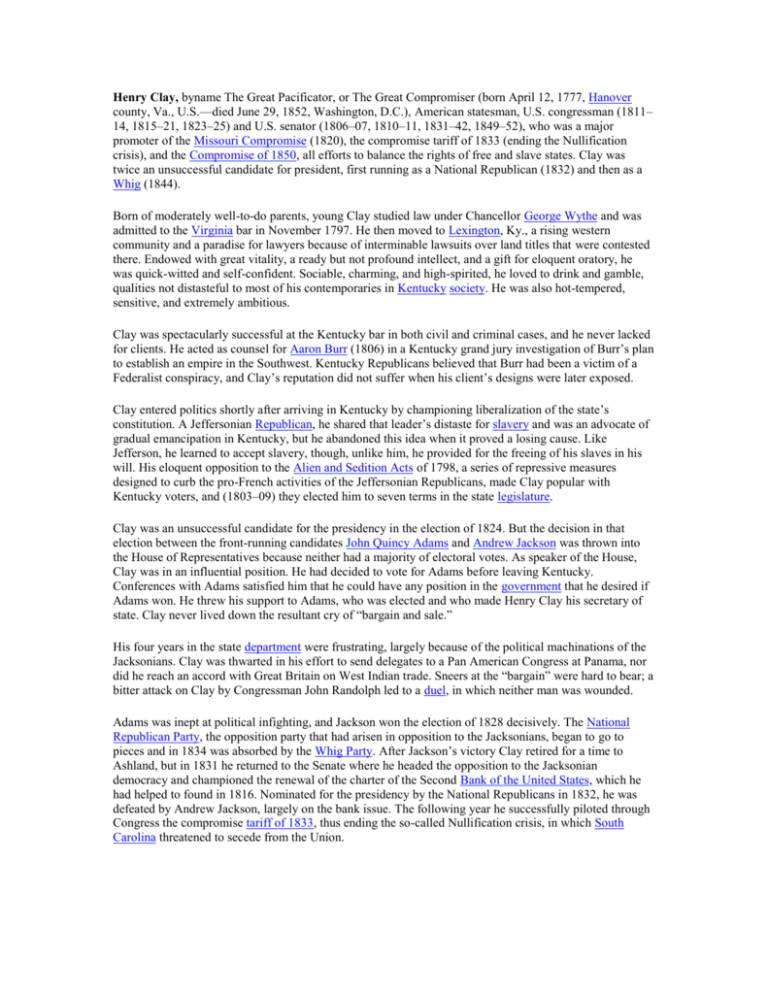

Henry Clay, byname The Great Pacificator, or The Great Compromiser (born April 12, 1777, Hanover county, Va., U.S.—died June 29, 1852, Washington, D.C.), American statesman, U.S. congressman (1811– 14, 1815–21, 1823–25) and U.S. senator (1806–07, 1810–11, 1831–42, 1849–52), who was a major promoter of the Missouri Compromise (1820), the compromise tariff of 1833 (ending the Nullification crisis), and the Compromise of 1850, all efforts to balance the rights of free and slave states. Clay was twice an unsuccessful candidate for president, first running as a National Republican (1832) and then as a Whig (1844). Born of moderately well-to-do parents, young Clay studied law under Chancellor George Wythe and was admitted to the Virginia bar in November 1797. He then moved to Lexington, Ky., a rising western community and a paradise for lawyers because of interminable lawsuits over land titles that were contested there. Endowed with great vitality, a ready but not profound intellect, and a gift for eloquent oratory, he was quick-witted and self-confident. Sociable, charming, and high-spirited, he loved to drink and gamble, qualities not distasteful to most of his contemporaries in Kentucky society. He was also hot-tempered, sensitive, and extremely ambitious. Clay was spectacularly successful at the Kentucky bar in both civil and criminal cases, and he never lacked for clients. He acted as counsel for Aaron Burr (1806) in a Kentucky grand jury investigation of Burr’s plan to establish an empire in the Southwest. Kentucky Republicans believed that Burr had been a victim of a Federalist conspiracy, and Clay’s reputation did not suffer when his client’s designs were later exposed. Clay entered politics shortly after arriving in Kentucky by championing liberalization of the state’s constitution. A Jeffersonian Republican, he shared that leader’s distaste for slavery and was an advocate of gradual emancipation in Kentucky, but he abandoned this idea when it proved a losing cause. Like Jefferson, he learned to accept slavery, though, unlike him, he provided for the freeing of his slaves in his will. His eloquent opposition to the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, a series of repressive measures designed to curb the pro-French activities of the Jeffersonian Republicans, made Clay popular with Kentucky voters, and (1803–09) they elected him to seven terms in the state legislature. Clay was an unsuccessful candidate for the presidency in the election of 1824. But the decision in that election between the front-running candidates John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson was thrown into the House of Representatives because neither had a majority of electoral votes. As speaker of the House, Clay was in an influential position. He had decided to vote for Adams before leaving Kentucky. Conferences with Adams satisfied him that he could have any position in the government that he desired if Adams won. He threw his support to Adams, who was elected and who made Henry Clay his secretary of state. Clay never lived down the resultant cry of “bargain and sale.” His four years in the state department were frustrating, largely because of the political machinations of the Jacksonians. Clay was thwarted in his effort to send delegates to a Pan American Congress at Panama, nor did he reach an accord with Great Britain on West Indian trade. Sneers at the “bargain” were hard to bear; a bitter attack on Clay by Congressman John Randolph led to a duel, in which neither man was wounded. Adams was inept at political infighting, and Jackson won the election of 1828 decisively. The National Republican Party, the opposition party that had arisen in opposition to the Jacksonians, began to go to pieces and in 1834 was absorbed by the Whig Party. After Jackson’s victory Clay retired for a time to Ashland, but in 1831 he returned to the Senate where he headed the opposition to the Jacksonian democracy and championed the renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, which he had helped to found in 1816. Nominated for the presidency by the National Republicans in 1832, he was defeated by Andrew Jackson, largely on the bank issue. The following year he successfully piloted through Congress the compromise tariff of 1833, thus ending the so-called Nullification crisis, in which South Carolina threatened to secede from the Union.

![[1.1] Prehistoric Origins Work Sheet](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006616577_1-747248a348beda0bf6c418ebdaed3459-300x300.png)