Latin - Matthew Dorough

advertisement

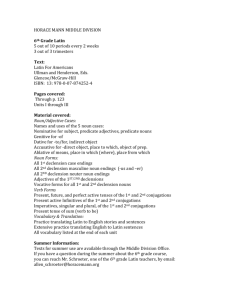

A Beginner’s Guide to Latin Pronunciation, Grammar, and Syntax By Matthew Dorough Contents Contents Introduction................................................................................................. v Chapter I – Pronunciation Alphabet............................................................................................ 3 Vowels .............................................................................................. 4 Consonants ....................................................................................... 5 Diphthongs ........................................................................................ 5 Chapter II – Grammar Nouns ............................................................................................... 9 Verbs .............................................................................................. 12 Chapter III – Syntax Word Order ..................................................................................... 17 Adjective Agreement ........................................................................ 17 Chapter IV – Repository Common Phrases ............................................................................. 21 Conjunctions .................................................................................... 24 Prepositions ..................................................................................... 24 Index ....................................................................................................... 25 iii Introduction v Introduction “Mille viae ducunt homines per saecula Romam” All roads lead to Rome: the Roman Empire was the primary political, cultural, economic, and martial influence over the Mediterranean and West Europe for approximately one thousand years. Even after the dissolution of the Roman Empire in the West, the legacy of Rome continued to shape the politics, culture, economy, and military of future empires and nations. One has to look no further than the Neoclassical architecture of the Capitol Building in Washington D.C. as a tangible manifestation of Rome’s enduring influence. A Dead Language? Latin is commonly considered a dead language by many people, which is understandable. After all, Latin is not the official, or de jure, language of any modern country and is certainly not the de facto language of any place. Despite this, Latin is still relevant today: Latin is used not just in the study of the Classics to read primary source documents on ancient history and literature, but also in the fields of science, medicine, and law. Whether using binomial nomenclature in biology to classify an organism (such as Homo Sapiens, Latin for “wise man”), the almost endless list of Latin phrases, such as modus operandi (mode of operating), caveat emptor (let the buyer beware), and pro bono publico (for the public good), in the courtroom, or the Latin abbreviations used in everyday writing (for example, etc. is an abbreviation of et cetera, which is Latin for “and others”), Latin is all around us. Look at the nearest, ubiquitous “EXIT” sign: exit translates to “he/she goes out.” Pull a coin out of your pocket: the motto of the United States, E Pluribus Unum, is Latin for “from many one.” Still Not Convinced? As Rome is such a powerful influence over our culture, the study of ancient Rome is necessary to understanding our modern world. In the pursuit of this study, the knowledge of the language of ancient Rome is highly useful, even if that knowledge is just a working knowledge of common Latin phrases and the fundamentals of the language. This is to say nothing of the value of knowing the language for the sake of language: Latin provides literally thousands of words for the English language through its cognates. With even limited knowledge of Latin, new perspectives appear on the English language, giving new facets of meaning to even common words. Take the words “inspiration” and “spirit;” these two English words are cognates of the Latin verb spirare, meaning “to breathe.” vi A Beginner’s Guide to Latin Via Appia After reading through and studying this guidebook, you will have taken the first step along your own road, one that will lead you inexorably to the ancient crossroads of our culture, Rome. As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome; once there, all roads are open before you. Please note that this guide is primarily intended for the neophyte Latin student, or as a concise reference guide to the fundamentals of Latin for the more experienced classicist. As such, this guide will restrict itself to discussion of the indicative, the subjunctive lying outside the scope of the guide. Similarly, this guide will be limited to only the first and second noun declensions and the present, past, and future tenses when conjugating verbs. Examples may include other declensions, but will always be in present tense. Chapter I Pronunciation Chapter 1 3 Pronouncing Latin Introduction Go ahead and say Caesar’s famous line, “Veni, vidi, vici.” You’ve most likely heard it and you may even know that it translates to, “I came, I saw, I conquered.” Did you also know that, more likely than not, you’ve never heard it pronounced correctly? There is nothing more basic to a language than proper pronunciation. Before learning grammar or syntax, it is imperative to have knowledge of how the language sounds. Latin, fortunately, is relatively simple to pronounce, having relatively simple rules with virtually no exceptions. The hardest part, as with any language, will be to train yourself to adhere to Latin’s rules of pronunciation without reverting back to English pronunciation. Alphabet Though we use the Roman alphabet today, as does most of the world, we do not use the exact same alphabet the Romans used: Roman: ABCDEFGHI KLMNOPQRST V XYZ English: ABCDEFGHI JKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ As you can see, the Romans did not possess the letters j, u or w. You will not encounter these letters while looking at ancient Latin text. However, in English transliteration of Latin, you will see the letter u when a vowel is used, and the letter v when a consonant is used; there is a difference in pronunciation, so Romans had to modify the sound of their v based on location of the letter within the word. Fortunately for us, we have the letter u, and no longer need to make such a fine distinction. As for j and w, there is no correlation in Latin. The letter j is merely an elongated i and w is, as the name implies, a double u in name and a double v in form. On a related note, Latin text makes no distinction between capital and lower case letters: Latin text is in all capitals. Also, there is no spacing in Latin, though some inscriptions use “bullets” to separate words. Again, modern students of Latin do not need to worry about these because English transliteration of Latin uses both lower case letters and spacing. 4 A Beginner’s Guide to Latin Vowels Latin has the same vowels as English (a, e, i, o, and u). Each vowel is pronounced the same way in all instances, the only reservation being that each vowel can be pronounced both long and short. The following table provides examples of both short and long vowel sounds. Remember, these vowel sounds are immutable. A E I O U Short vowel aqua, casa et, deus, exit nihil, ignis corpus, toga dux, dum, urbs Long vowel crās, extrā dē, dēfendo virī, īra, īnferior prō, sōl, agō cūra, iūstus As in English “father” “establish” “technique” “tome” “put” As you can see from the Latin inscription to the left, which is located in the Coliseum, there are no spaces and there are no lower case letters. Also take note of the lack of the letters j, u, and w. The inscription below makes use of bullets to space its words. Chapter 1 5 Consonants Latin consonants are similarly simple to pronounce and likewise immutable. The biggest difference between English and Latin pronunciation is that Latin always uses the hard consonant sound, never the soft sound. The following table notes exceptions to English consonant pronunciation. C G H Q V X Rule Always pronounced as k Never pronounced as j Never silent Never pronounced as k Pronounced as w Never pronounced as z Example Caesar = ky∙ sar magistra = ma∙ gee∙ stra herba = hayr∙ ba qui = kwee Veni, vidi, vici = we∙ nee, wee∙ dee, wee∙ kee Ulixes = ool∙ eecks∙ es Diphthongs Latin has six diphthongs that, again, are only pronounced one way. ae au ei eu* oe ui** English Equivalent ai as in aisle ou as in mouse ei as in feign Not found in English oi as in boil Can be heard in “chewy” Latin Example Caesar laudo deinde Seleucid proelium huius, cuius, huic, cui, hui *Rarely found in Latin. The sound is made by quickly combining the two vowel sounds. **The examples given constitute the exhaustive list of words that use this diphthong. Chapter II Grammar Chapter 2 9 The Fundamentals of Latin Grammar Introduction Latin grammar is actually relatively simple to learn: it is a rather formulaic system with very few exceptions. Latin, like English, is a language that uses a combination of nouns and verbs linked by conjunctions and prepositions to describe objects and actions, place and possession. Endings and Stems The most prominent aspect of Latin is its system of endings: the end of a noun will tell you if the noun is the subject or direct object and the end of a verb will tell you who is doing the action. Navigamus ad insulam. We sail to the island. In the above example, the ending –mus tells us that the verb is in first person plural, and the ending –am on the noun tells us that the island is the direct object. This system often means that Latin words will be relatively long, but that the sentences will contain relatively few words, as each word carries multiple ideas and performs multiple roles. Taking the above example again, the verb, navigamus, carries the pronoun (we), the action (sail), and the tense (present). From that one word, we know that we are currently sailing. We know where to add these endings based on the stem of a noun or verb. These stems will be discussed with more detail later in the chapter. Nouns Declension and Feminine, Masculine, and Neuter Endings Latin divides its nouns into five different declensions. For our sake, we will only look at the two most commonly used declensions, the first and second; the third, fourth, and fifth declensions are rarely seen, as they mostly encompass nouns that fall outside of the first and second declension as exceptions. The first declension contains mostly nouns which have the feminine ending and the second declension contains mostly nouns which have masculine and neuter endings. This is merely a convenient rule of thumb: it is important to bear in mind that a noun’s gender does not determine its declension. 10 A Beginner’s Guide to Latin Noun Declension Noun declension describes the process and system whereby Latin nouns achieve a specific meaning. Each noun has a gender and a stem: the gender determines which declension is needed, and the stem is the root where each ending is attached. The ending is determined by how the noun is functioning in the context of its use, which will determine number and case: number is whether or not the noun is singular or plural, and case is the noun’s function in the sentence. There are five cases in Latin: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, and ablative. The stem is best determined by dropping the genitive singular ending off of a noun. Nominative case is used when a noun is the subject of a sentence; that is, the noun that is performing the action. Vir scribet litteras. The man writes the letter. In this example, the man, vir, is the noun performing the action of writing the letter, thus it is in the nominative case. Genitive case is used when a noun possesses another; that is, the noun that owns is the one that is declined in the genitive, not the noun that is owned. Nuntius portat litteras viri. The messenger carries the man’s letter. In this example, letter belongs to the man, viri; man is therefore in the genitive case. The possessed noun is generally followed by its owner. Dative case is used when a noun is the indirect object; that is, the noun that receives the verb’s action. Nuntius donat litteras regi. The messenger gives the letter to the king. In this example, the messenger gives the letter to the king, regi. The king is the indirect recipient of the action: the letter is acted upon, but the king receives the consequence. Accusative case is used when a noun is the direct object; that is, the noun that the verb directly acts upon. Rex leget litteras. The king reads the letter. In this example, the king reads the letter, litteras, which makes the letter the direct recipient of the action. Ablative case is used to modify a noun in time, place, or manner. It is frequently used with adverbs and prepositions. Chapter 2 11 Rex ducet milites in bello. The king leads the soldiers in war. In this example, the king leads the men in war, bello. War is conjugated in the ablative because it is modified by the preposition in. First Declension Feminine – endings highlighted Singular Nominative ter´ra Genitive ter´rae Dative ter´rae Accusative ter´ram Ablative ter´rā Plural ter´rae ter´rārum ter´rīs ter´rās ter´rīs Second Declension Masculine – endings highlighted Singular Nominative por´tus Genitive por´tī Dative por´tō Accusative por´tum Ablative por´tō Plural por´tī portō´rum por´tīs por´tōs por´tīs Neuter – endings highlighted Nominative Genitive Dative Accusative Ablative Singular cae´lum cae´lī cae´lō cae´lum cae´lō Plural cae´la caelō´rum cae´līs cae´la cae´līs 12 A Beginner’s Guide to Latin Verbs The Infinitive Verbs are also dependent on endings and stems. The stem of a verb is simpler to determine than that of a noun: merely drop the –are, -ere, or –ire off the infinitive. The infinitive form is the default form for a verb, and means to + action. For instance, celebrare means “to celebrate,” currere means “to run,” and scire means “to know.” Present Indicative Conjugation Each verb can be conjugated to relate a different tense, such as present, past, or future. Like a noun, each ending within a tense relates information on number. A verb ending will also tell you who is performing the action. The present indicative is the most basic verb conjugation in Latin and, as the name denotes, expresses that an action is currently taking place. First Person Second Person Third Person Singular -ō = I -s = you -t = he, she, it Plural -mus = we -tis = you -nt = they Example of a Present Indicative Conjugated Verb Begin with the infinitive vidēre, which means “to see.” Drop the -ēre ending and add the present indicative verb endings: Videō I see, am seeing, do see Vides you see, are seeing, do see Videt he, she, it sees, is seeing, does see Videmus we see, are seeing, do see Videtis you see, are seeing, do see Vident they see, are seeing, do see Chapter 2 13 Perfect Indicative Conjugation The perfect indicative expresses actions that took place in the past. The perfect tense uses a different stem than the present or future tenses. First Person Second Person Third Person Singular -ī -istī -it Plural -imus -istis -ērunt Example of a Perfect Indicative Conjugated Verb Vidi I saw, have seen, did see Vidisti you saw, have seen, did see Vidit he, she, it saw, has seen, did see Vidimus we saw, have seen, did see Vidistis you saw, have seen, did see Viderunt they saw, have seen, did see Future Indicative Conjugation The future indicative expresses actions that will take place in the future. First Person Second Person Third Person Singular -bō -bis -bit Plural -bimus -bitis -bunt 14 A Beginner’s Guide to Latin Example of a Future Indicative Conjugation Videbo I shall see Videbis you will see Videbit he, she, it will see Videbimus we shall see Videbitis you will see Videbunt they will see Chapter III Syntax Chapter 3 17 Word Order Easy to Learn… Latin has no strict rules on sentence structure or word order since the endings on nouns and verbs take care of most of each sentence’s content. No matter how scrambled a sentence becomes, the meaning can still be derived by determining the number and case of each noun, and the number and tense of each verb. Signum demonstrat viam. The sign shows the way. Viam demonstrat signum. The sign shows the way. Demonstrat signum viam. The sign shows the way. While it is recommended that words that modify each other be grouped together within the sentence, it is by no means necessary. Hard to Master Because Latin lacks a stringent set of syntax rules, there are times where it is difficult to decipher what is going on if words are not grouped well. While ancient Latin writing is what it is, when writing your own sentences, try to follow the form of an English sentence, so as to minimize confusion and ambiguity. In general, adjectives should be next to the noun they modify, the possessed object ought to precede its owner, and what follows a preposition must be the object that the preposition modifies. Adjective Agreement Latin adjectives have no gender. Instead, they change gender depending on the noun they modify, and must agree with that noun in number and case. Via bona Good road Bona facta Good deeds Bonus cibus Good food Chapter IV Repository of Useful Terms Chapter 4 21 Repository Common Phrases A a fortiori, a posteriori, a priori, ab absurdo, ad absurdum, ad hoc, ad hominem, ad infinitum, Agnus Dei, alias, alibi, alma mater, alter ego, Anno Domini (A.D.), annuit coeptis, ante bellum, from the stronger from the latter from the former from the absurd to the absurd to this to the man to infinity Lamb of God at another time, otherwise elsewhere nourishing mother another I the year of our Lord he nods at things being begun, he approves our undertakings before the war B bona fide, good faith C caput mundi, carpe diem, cave canem, caveat emptor, circa, cogito ergo sum, Corpus Christi, corpus delecti, cui bono, cum grano salis, cum laude, curriculum vitae, head of the world sieze the day beware of the dog let the buyer beware around I think, therefore I am body of Christ body of the offence good for whom? with a grain of salt with praise course of life D de facto, de jure, de novo, by deed by law from the new 22 deus ex machina, dum spiro spero, A Beginner’s Guide to Latin a god from a machine while I breathe, I hope E e pluribus unum, Ecce Homo, emeritus, ergo et alii (et al.), et cetera (etc.), ex ante, ex gratia, ex post, excelsior, one from many Behold the Man veteran therefore and others and the rest from before from kindness from after higher F fac simile, make a similar thing G genius loci, spirit of place H habeas corpus, you should have the body I Ibidem (ibid), id est (i.e.), incognito, in medias res, in toto, in vitro, in vivo, inter alia, ipso facto, in the same place that is with one’s identity concealed into the middle of things in all in glass in life among other things by the fact itself M Magna Carta, magna cum laude, magnum opus, mea culpa, memento mori, modus operandi, Great Charter with great praise great work my fault remember you will die method of operating Chapter 4 23 N nemo, non sequitur no one it does not follow O orbis non sufficit, the world is not enough P pro bono publico, for the public good Q quid pro quo, this for that R re, requiescat in pace, res gestae, rigor mortis, in the matter of let him/her rest in peace things done stiffness of death S S.P.Q.R., semper fidelis, sic, spiritus mundi, statim, status quo, stet, sub poena, The Senate and the People of Rome always faithful thus, just so spirit of the world immediately the situation in which let it stand under penalty T tabula rasa, tempus fugit, terra firma, tu quoque, blank slate time flees solid land you too V veni, vidi, vici, verbatim, versus, veto, via, vice versa, vox populi, I came, I saw, I conquered word for word towards I forbid by the road, by way of with position turned voice of the people 24 A Beginner’s Guide to Latin Conjunctions aut, aut… aut dum, et, et… et neque, neque… neque quod, sed, si, or either… or while and both… and nor neither… nor because but if Prepositions ab, ad, ante, circa, circum, contra, cum, de, ex, extra, in, inter, non, ob, per, post, pro, prope, sine, sub, super, trans, versus, by to before about around against with from from outside, beyond in, into, on, upon between, among not toward, because of through after for, in behalf of, in front of near without under over, above across towards Index A Ablative case, 10 Accusative case, 10 adjective, 17 alphabet, 3 C capital, 3 Conjugation, 12 consonants, 5 D Dative case, 10 declension, 9, 10 diphthongs, 5 direct object, 9, 10 E ending, 9, 10, 12 F feminine, 9 future indicative, 13 G Genitive case, 10 grammar, 3, 9 I infinitive, 12 L lower case, 3 M masculine, 9 N neuter, 9 25 26 Nominative case, 10 P perfect indicative, 13 present indicative, 12 S subject, 9, 10 V vowels, 4 A Beginner’s Guide to Latin